Barnstorming

Barnstorming was a form of entertainment in which stunt pilots performed tricks—either individually or in groups called flying circuses. Devised to "impress people with the skill of pilots and the sturdiness of planes",[1] it became popular in the United States during the Roaring Twenties.[2]

Barnstormers were pilots who flew throughout the country selling airplane rides and performing stunts; Charles Lindbergh first began flying in this capacity.[3] Barnstorming was the first major form of civil aviation in the history of aviation.

History

Background

The Wright brothers and Glenn Curtiss had early flying exhibition teams, with solo flyers like Lincoln Beachey and Didier Masson also popular before World War I, but barnstorming did not become a formal phenomenon until the 1920s. The first barnstormer, taught to fly by Curtiss in 1909, was one Charles Foster Willard, who is also credited as the first to be shot down in an airplane when an annoyed farmer broke his propeller firing a squirrel gun.[4]

During World War I, the United States manufactured a significant number of Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” biplanes to train its military aviators and almost every U.S. airman learned to fly using the plane. After the war the U.S. federal government sold off the surplus material, including the Jennys, for a fraction of its initial value (they had cost the government $5,000 but were being sold for as low as $200).[5] This allowed many servicemen who already knew how to fly the JN-4s to purchase their own planes. The similar-looking Standard J-1 biplane was also available.

At the same time, numerous aircraft manufacturing companies sprang up, most failing after building only a handful of planes. Many of these were reliable and even advanced designs which suffered from the failure of the aviation market to expand as expected, and a number of these found their way into the only active markets—mail carrying, barnstorming, and smuggling. Sometimes a plane and its owner would drift between the three activities as opportunity presented.

Combined with the lack of Federal Aviation Regulations at the time, these factors allowed barnstorming to flourish.

Growth and heyday

Barnstorming was performed not only by former military men, but also by women, minorities, and women minorities (e.g., Bessie Coleman).[6] For example, on July 18, 1915, Katherine Stinson became the first woman in the world to perform a loop.[5] Bessie Coleman, an African-American woman, “not only thrilled audiences with her skills as a barnstormer, but she also became a role model for women and African Americans. Her very presence in the air threatened prevailing contemporary stereotypes. She also fought segregation when she could by using her influence as a celebrity.”[6]

“More than any single event, Lindbergh's historic 1927 flight made Americans aware of the potential of commercial aviation, and there followed a boom in aviation activity during 1928 and 1929.”[3] In fact, Charles Lindbergh engaged in barnstorming in his early years; Errold Bahl hired him as an assistant, and as a promotional stunt, Lindbergh “volunteered to climb out onto the wing and wave to the crowds below,” which came to be known as “wing-walking.”[1]

Regulation and decline

The sensational journalism and economic prosperity that marked the Jazz Age in the United States allowed barnstormers to publicize aviation and eventually contributed to bringing about regulation and control.[3] In 1925, the U.S. government began regulating aviation, when it passed the Contract Air Mail Act, which allowed the U.S. Post Office to hire private airlines to deliver mail with payments made based on the weight of the mail. The following year, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Air Commerce Act, which shifted the management of air routes to a new branch in the Department of Commerce, which was also responsible for “licensing of planes and pilots, establishing safety regulations, and general promotion.”[7][8]

Barnstorming “seemed to be founded on bravado, with ‘one-upmanship’ a major incentive.”[9] By 1927, competition among barnstormers resulted in their performing increasingly dangerous tricks, and a rash of highly publicized accidents led to new safety regulations, which led to the demise of barnstorming. Spurred by a perceived need to protect the public and in response to political pressure by local pilots upset at barnstormers stealing their customers, the federal government enacted laws to regulate a fledgling civil aviation sector.

The laws included safety standards and specifications that were virtually impossible for barnstormers to meet, and restrictions on how low in altitude certain tricks could be performed (making it harder for spectators to see what was happening). The military also stopped selling Jennys in the late 1920s. This made it too difficult for barnstormers to make a living. Clyde Pangborn, who was pilot of the two-man aviation team who were the first to cross the Pacific Ocean nonstop in 1931, ended his barnstorming career in 1931.[10] Some pilots, however, continued to wander the country giving rides as late as fall 1941.

Performances

Planning

“Barnstorming season” ran from early spring until after the harvest and county fairs in the fall. Most barnstorming shows started with a pilot, or team of pilots flying over a small rural town to attract local attention. They would then land at a local farm (hence the term “barnstorming”) and negotiate for the use of a field as a temporary runway from which to stage an air show and offer airplane rides. After obtaining a base of operation, the pilot or group of aviators would “buzz” the village and drop flyers.[1] In some towns the arrival of a barnstormer or an aerial troupe would lead to a town-wide shutdown as people attended the show.

Stunts

Barnstormers performed a variety of stunts, with some specializing as stunt pilots or aerialists. Stunt pilots performed a variety of aerobatic maneuvers, including spins, dives, loop-the-loops and barrel rolls. Meanwhile, aerialists performed feats of wing walking, stunt parachuting, midair plane transfers, or even playing tennis, target shooting, and dancing on the plane's wings. Other stunts included nose dives and flying through barns, which sometimes led to pilots crashing their planes.[5]

Business

Barnstormers offered plane rides for a small fee. Charles Lindbergh, for example, charged five dollars for a 15-minute ride in his plane.[3] However exciting and glamorous, it was not an easy way to make a steady living. To make ends meet, the barnstormers—including Charles Lindbergh—had to moonlight as flying instructors, handymen, and sometimes even as gas station attendants.[1] Barnstormers often traded plane rides for room and board, both for commercial lodging and in private homes.[3]

Flying circuses

Although barnstormers often worked in solitude or in very small teams, some also put together large “flying circuses” with several planes and stunt people. These acts employed promoters to book shows in towns ahead of time. They were the largest and most organized of all of the barnstorming acts. Some of the most famous were “The Five Blackbirds” (an African American flying group), “The Flying Aces Air Circus,” “The 13 Black Cats,” “Mabel Cody’s Flying Circus,” “Inman Brothers Flying Circus,” and the “Gates Flying Circus,”[11] to which Clyde Pangborn belonged until 1928.

Significance

At an individual level, barnstorming “provided an exciting and challenging way to make a living, as well as an outlet for their creativity and showmanship” for many pilots and stunt fliers. For example, it allowed Charles Lindbergh to make a marginal living, and he always spoke fondly of the “old flying days” and the freedom of movement. It was during a barnstorming tour in Minnesota and Wisconsin in 1923 that led to his “decision to pursue further formal instruction with the U.S. Army Air Service.”[3]

Cadet Squadron 23 at the United States Air Force Academy is known as the “Barnstormers.”[12]

Notable barnstormers

- Jimmy Angel

- Pancho Barnes

- Lincoln Beachey

- Lillian Boyer

- Carter Buton

- Alan Cobham

- Bessie Coleman

- Doug Davis

- Carl Ben Eielson

- Roland Garros

- Tex Johnston

- Hubert Julian

- William Carpenter Lambert

- Charles Lindbergh

- Didier Masson

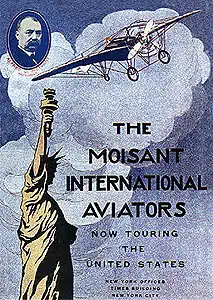

- John Moisant

- Clyde Pangborn

- Louis Paulhan

- Adolphe Pegoud

- Wiley Post

- Harriet Quimby

- Abraham Whalomie Raygorodsky

- René Simon

- Dean Smith

- Roscoe Turner

- Ernst Udet

- Jerrie Cobb

In popular culture

Books

- William Faulkner's 1935 novel Pylon tells the story of a group of barnstormers

- Nevil Shute's 1951 novel Round the Bend gives a detailed account of the activities of Alan Cobham's National Aviation Day. Archive sources show that Shute, in research for writing the book, wrote to Cobham to check details.

- Many of Richard Bach's novels feature modern barnstormers as protagonists, or otherwise incorporate barnstorming[11]

- Philip Jose Farmer's 1982 book A Barnstormer in Oz featured a barnstorming pilot named Hank Stover

- In the Peanuts comic strip, Snoopy's alter ego, the World War I Flying Ace, states that he may do a little barnstorming after the war

- The novel “The Flying Circus” by Susan Crandall follows the exploits of a trio of individuals who come together to create their own barnstorming troupe.

Movies and TV

- The Tarnished Angels (1957) – melodrama by Douglas Sirk based on the Faulkner novel about barnstorming

- Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965) – comedy about the “pioneer era” (1903-1914) of air racing and barnstorming in Europe

- Ace Eli and Rodger of the Skies (1973) – movie by Steven Spielberg starring Cliff Robertson as a Jenny pilot who barnstorms with his young son

- The Great Waldo Pepper (1975)

- Nothing by Chance (1975) – documentary by Hugh Downs about the biplanes that barnstormed across America in the 1920s

- Days of Heaven (1978) – movie by Terrence Mallick in which a barnstorming troupe visits a farm and performs

- The Gypsy Moths (1969) – American drama film directed by John Frankenheimer starring Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr, based on the novel of the same name by James William Drought

- The MTV show Nitro Circus features Travis Pastrana, Jolene Van Vugt, and Erik Roner wing-walking on a biplane without chutes or harnesses

- The Fall Guy (1981-1986)- An action/ adventure television series originally airing on ABC. The show was about a stuntman who moonlights as a bounty hunter using his skills as a stuntman to catch the bad guys. A scene in the intro shows of a biplane running through a farm field and crashing/ “barnstorming” into the side of a barn.

Video games

- In 1982 Activision produced a Barnstorming game cartridge for the Atari 2600

- In RollerCoaster Tycoon 2, the “Barnstorming Roller Coaster” has coaster cars that are replica biplanes

- In RollerCoaster Tycoon 3's Wild! Expansion Pack, a “Barn Stormer” ride can be built

In 2004 Murware produced a Barnstorming (video game) Barnstormers for Android

Music

- “The Immelmann Turn,” by Al Stewart, a song set in the 1920s barnstorming era which refers to an aerobatic maneuver of the same name

See also

References

- "Daredevil Lindbergh and His Barnstorming Days". PBS. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- David H. Onkst. "Clyde 'Upside-Down' Pangborn". U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Bruce L. Larson (Summer 1991). "Barnstorming with Lindbergh" (PDF). Minnesota History. Minnesota Historical Society. pp. 231–238.

- "Charles F. Willard, Who is Trying to Perfect Monoplane; Bullet Hit Airship of Boston Aviator; Charles F. Willard of Hull Has Become Prominent in Aeronautics". Boston Journal. Boston, Mass. June 2, 1910. p. 3.

It was a Boston man who figured in the first case recorded of an aeroplane brought to earth by a bullet...Charles F. Willard, whose machine was wrecked in Joplin, Mo., during a cross-country flight

- AP News (February 2, 1977). "Charles F. Willard Is Dead". The New York Times. New York. p. 17.

- Willard, Charles F. (February 1956). Frank H. Ellis (ed.). Frail were my Wings. Flying Magazine. pp. 31, 70.

- "Barnstorming History". Southern Biplane Adventures. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- David H. Onkst. "Women in History: Bessie Coleman". USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Andrew Glass (May 20, 2013). "Congress passed Air Commerce Act, May 20, 1926". Politico.

- "The Air Commerce Act of 1926". AvStop Online Magazine. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Aviation Pioneers". National Park Service. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Priscilla Long (October 12, 2005). "Pangborn, Clyde Edward (1894-1958)". HistoryLink.

- "The History of Barnstorming". May 31, 2011. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- "CS-23 Patch "Barnstormers"". Association of Graduates United States Air Force Academy. USAFA. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.