Barony of Bonshaw

The Barony of Bonshaw, previously known as Bollingshaw, was in the old feudal Baillerie of Cunninghame, near Stewarton in what is now North Ayrshire, Scotland.

The History of Bonshaw

The Irvines and Boyds

William Irvine (c.1298) (also known as William de Irwin) was a clerk in the royal chancellery and protégé of Bernard, Abbot of Arbroath and Chancellor of Scotland; he was granted land in Aberdeenshire in 1323 by Robert the Bruce for faithful service. This grant included a defensive work known as the Drum Tower, thus William became the first Laird of Drum. The family had previously held the lands of Bonshaw and took their name from the village of Irvine in Annandale.[1]

An Irvinehill Farm is still to be found near Kennox which may relate to this family name or may simply signify that a good view of Irvine is to be had from this eminence. Alexander Smith (died 1938) and his spouse Robina Robb (died 1959) farmed Irvinehill in the mid 20th century and were buried in the Stewarton cemetery.

The Bonshaw barony and estate originally included Bonnyton, Hutt, Moorhead or (Girgenti), Sandielands, Bogflat, and Bankend as well as High and Laigh Chapelton.[2]

Bonshaw, formerly Bollingshaw, Bonstonshaw, or Bollynschaw, was a small estate and Barony of the Boyd's, a cadet of the Boyds, Lords of Kilmarnock.[3]

In 1482, James, Lord Boyd, was granted the lands of Bollynschaw, Chapelton, Crevoch, and others, reserving the tenement of the lands to his mother, Mary, Lady Hamilton.[4]

A daughter of the Bonshaw family, Margaret Boyd, was a mistress to James IV, living at Duchal Castle where her bastard son, Alexander Stewart, was born, became Archbishop of St. Andrews and dying at the Battle of Flodden with his father. She later married John Mure of Rowallan Castle. In 1592 Robertson records that Barbara Lawson, daughter of John Lawson owned the lands of Bonshaw and that by the 1690s they were in the hands of the Dundonald family, the Cochranes, the mansion house now being in utter ruins. A Charter of sasine under the Great Seal of Queen Anne was issued to the successors of the deceased Alexander Cochrane of Bollingshaw on 20 March 1706.[5] The mansion house has been long demolished and all that remains are the entrance gateposts, an ice house and possibly the Moot hill and justice hill.

The first OS maps show the horse mill outside the detached building in front of the farm and stepping stones across the Glazert on a path running up to Crossgates. The later map shows what appears to be a small lake with a total re-arrangement of the formal gardens from the previous map.

Alexander Reid and the Hutt Knowe

Near to the existing farm is the Hut Knoll[6] or more commonly Hutt Knowe (Huit is a 'stack' and Knowe is a 'knol' or low hill), also known as Bonshaw or Bollingshaw Mound, 17 m in diameter and 2.7 m high, variously described as a mounded corn-kiln or lime kiln, but unlike any other known example in the region.[7]

Corn-drying kilns were often built into sloping ground or existing mounds.[8] It has large integral basal stones and was described in 1890[6] as having culverts or 'penns' in its sides, although these are not visible today. A dwelling by the name of 'Hutt' existed at this location in the 1740s.[9]

In 1828, Alexander Ferguson Reid inherited the estate, he was known as the "Ayrshire Genius" and was an inventor and collector of antiquities, as well as geological and natural history specimens. Reid dug into this Druidical Mound or Moot Hill several times and found nothing to help explain its age or purpose.[3] Most maps do not show the ice house which lies to the east of the driveway and some confusion in the descriptions may have arisen from misidentification of the ice house, limekiln and the Hutt Knowe. In the grounds of the present farm are curved ditches which are shown to have held water, either as ornamental ponds or for some practical purpose now unknown. The site had an apple orchard within the last 50 years or so, for John Hastings remembers raiding it.[10]

Given that Bonshaw was the 'seat' of the Bollingshaw Barony it is likely that in addition to any other uses the two mounds of Hutt Knowe and Knockenlaw were respectively the Moot hill and justice or Gallows hill of the barony, where the laird would exercise his right of 'pit and gallows' until 1747 when the right was abolished as one of many measures linked to the 1745 Jacobite rising.

Isabella Montgomerie of Dalmore House married Robert Reid of Bonshaw (b 1827, d 1887).

Dr. Duguid's visit to Bonshaw

Dr. Duguid in a work of well informed fiction[11] visited 'Bonnshie', circa the 1840s and lists some of the items in Reid's collection, including garden seats made of bog-oak from Auchentiber Moss, his grandfathers Ferrara sword with which he fought at Drumclog, the first winnowing machine and teapot in Stewarton, devices for catching robbers, etc. etc. He had the stirrups from the horse that the Earl of Eglinton was riding when he was shot and killed by the gauger Mungo Campbell. The 'Hut Knoll' is described as a 'humplock', built by the 'wee Pechs' or by Druids.

In a small planting is described the place where Alexander Watt, a Jacobite participant in 1745 rebellion, hid his silver when he was forced to flee to Ireland. Duguid comments that it is said that Reid has A fouth o'auld nicks nackets (nick-nacks) and that Captain Francis Grose himself (the author, artist & historian, and friend of Robbie Burns) was envious of the collection.[11]

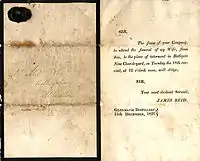

The Bonshaw Visitor's Book

1901

1901 1903

1903 1906–1907

1906–1907 Charles Rennie Mackintosh style. 1909–1915

Charles Rennie Mackintosh style. 1909–1915 Boats by Janet Reid

Boats by Janet Reid Peasant girl collecting water by W Reid

Peasant girl collecting water by W Reid Mountains and boat by M Reid

Mountains and boat by M Reid Boats and Bluetits by Mary Montgomerie of Dalmore House

Boats and Bluetits by Mary Montgomerie of Dalmore House

See also

References

- Strawhorn, John (1985). The History of Irvine. Pub. John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-140-1. p. 4.

- Robertson, George (1820). Topographical Description of Ayrshire; more Particularly of Cunninghame: together with a Genealogical account of the Principal families in that Bailiwick. Cunninghame Press. Irvine.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow.

- Archaeological & Historical Collections relating to the counties of Ayrshire & Wigtown. Edinburgh : Ayr Wig Arch Soc. 1882, p. 143

- Bonshaw Papers. Scottish National Archives.

- Smith, John (1895). Prehistoric Man in Ayrshire. Pub. Elliot Stock.

- Linge, John (1987). Re-discovering a landscape: the barrow and motte in north Ayrshire. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Vol. 117. p. 28.

- Fairhurst, Horace (1967–68). Rosal:a Deserted Township in Strath Naver, Sutherland. Proc Soc Nat Hist V.100. P. 152.

- Roy's Map

- Hastings, John (2006), the Younger. Oral Communications to Roger S.Ll. Griffith.

- Service, John (Editor) (1887). The Life & Recollections of Doctor Duguid of Kilwinning. Pub. Young J. Pentland. Pps.81- 83.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bonshaw, Ayrshire. |

- General Roy's Military map of Scotland.

- Details of the De Soulis, De Morville and other Cunninghame families.

- Video and commentary on 'Water Meetings', Bankend Farm & ford