Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution

The Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution (also known as BRLSI) is an educational charity based in Bath, England. It was founded in 1824 and provides a museum, an independent library, exhibition space, meeting rooms and a programme of public lectures, discussion groups and exhibitions related to science, the arts and current affairs.

| |

| Founded | 1824 |

|---|---|

| Type | Educational charity |

| Focus | The promotion and advancement of science, literature and art in the city of Bath |

| Location |

|

Members | approx 500 |

| Website | www.brlsi.org |

Origins: Science Lecturing in Georgian Bath

The early eighteenth century witnessed a vogue for science lecturing in the wake of the pioneering endeavours of scientists such as Isaac Newton, Edmund Halley and Robert Hooke and the founding of the Royal Society in 1662. Bath had long attracted students of chemistry and medicine keen to legitimise claims for the curative properties of its hot spring waters, and soon the patronage of the aristocracy heralded the first wave of the city's Georgian popularity. The first commercial public science (or natural philosophy) lecture was presented by John Theophilus Desaguliers in 1724, explaining the phenomenon of a total eclipse of the sun, which had occurred in May of that year. The lecture may well have been held at Mr. Harrison's Assembly Rooms in Terrace Walk, already becoming a popular venue for the well-heeled visitor to the city. Although it would continue to be host to such itinerant lecturers, it would be another 53 years before the first of Bath's scientific societies was formed.[1]

The Bath and West Society

In 1777 Edmund Rack, the son of a Norfolk labouring weaver, founded the first of Bath's scientific and literary societies. Although partly modelled on the Royal Society of London and other such institutions, Rack was particularly concerned with agricultural and planting improvements in the West Country and so the society would be known as the Bath and West of England Society for the Encouragement of Agriculture, Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (later to become the Royal Bath and West of England Society, its home moving from Bath to Shepton Mallet in 1974 after 196 years with its headquarters in the city). The Bath society published Aims, Rules and Orders and, like its London progenitor, offered prizes or 'premiums' for enterprising projects. These included improvements in areas such as animal husbandry, farm implements and country crafts.[2] Members included William Smith, the 'father of English Geology', whose connections through the society would encourage his geological work in identifying the relationship between rock strata and the distinctive fossils associated with them.[3]

The Bath Philosophical Societies

The first of three Philosophical Societies was inaugurated in 1779, founded by Thomas Curtis with Edmund Rack once more at the helm, as secretary. With the aim of being a select Literary Society for the purpose of discussing scientific and philosophical subjects and making experiments to illustrate them,[4] the model for this venture would have been provincial discussion groups such as the Lunar Society. The Bath Philosophical Societies did not quite have the staying power of the Birmingham-based forum and after three incarnations quietly folded. Despite its failure to thrive the society could still boast influential and important subscribers including William Herschel (whose discovery of Uranus was made in 1781 whilst a resident of the city), and Joseph Priestley who at Bowood House in nearby Calne was embarking on his most important scientific investigations on different kinds of air (including his discovery of oxygen).[5]

The Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution

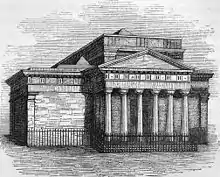

It was in 1824 that the most robust of Bath's literary and scientific societies was founded. Its first home was a grand new building designed by George Allen Underwood on the site of Harrison's Assembly Rooms in Terrace Walk (which had been destroyed by fire in 1820). The Duke of York was the first patron of the Institution and its first president was Marquis of Lansdowne (the son of Joseph Priestley's one-time employer, Lord Sherburne). The first curator of the Institution was William Lonsdale. Lonsdale was a geologist and his study of fossils found in South Devon limestones informed the work of Adam Sedgwick and Roderick Murchison in establishing (after much controversy) the basis for a geological period between the Carboniferous and the Silurian: the Devonian Period.[6] The 'Royal' prefix was added when Queen Victoria continued the patronage bestowed upon the Institution by The Duke of Clarence (later William IV).

Some notable members of the BRLSI

- Leonard Jenyns (later Blomefield) (1800–1893) founded the Bath Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club in 1855, which operated under auspices of the BRLSI. Jenyns was a lifelong friend of Charles Darwin and famously turned down the opportunity to be the naturalist aboard HMS Beagle's voyage to South America. Jenyns recommended the young Charles Darwin to Captain Robert FitzRoy.[7]

- Charles Moore (1815–1881) was an eminent geologist whose most spectacular fossil finds came from a single strata 15 cm-thick at Strawberry bank near Ilminster. His discovery of what he named the 'saurian, fish and insect bed' was made after observing two boys rolling a pebble, or nodule, to each other, which upon splitting apart revealed a beautifully preserved fossil fish of the genus Pachycormus. In the following years he amassed a collection of hundreds of marine specimens from the site, many displaying remarkable soft tissue preservation.[8] In 2010 the BRLSI received a grant of £62,250 from the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation for a research and conservation project devoted to Moore's Strawberry Bank fossil collection.

Collections

The Institution's antiquarian library contains over 7000 volumes, including the Jenyns and the Broome natural history libraries. Its archives contain bound volumes of letters from eminent scientists and naturalists such as Charles Darwin, Professor John Stevens Henslow and Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker. Smaller collections cover theology, government, travel and local history. Four paintings by Andrea Casali and a photography collection by the Reverend Francis Lockey (1796–1869) are also featured.

Building

In 1932 the Institution moved to 16–18, the Georgian Queen Square, a Grade I listed Greek Revival building designed by John Pinch the younger in 1830[9] as a road improvement scheme entailed the demolition of the Terrace Walk.

References

- Science Lecturing in Georgian Bath.. Fawcett, Trevor. Cited in Chapter 11 Innovation and Discovery: Bath and the Rise of Science.

- Bath Scientific Societies and Institutions. Fawcett, Trevor. Cited in Chapter 12 Innovation and Discovery: Bath and the Rise of Science.

- Of Canals and Quarries – The Bath Geologists. Williams, Matt. Cited in Chapter 3 Innovation and Discovery: Bath and the Rise of Science.

- Bath – Some Connections With Science Page 68.

- Airs and Waters. Ford, Peter and Rolls, Roger. Cited in Innovation and Discovery: Bath and the Rise of Science. Pages 27–29.

- Of Canals and Quarries – The Bath Geologists. Williams, Matt. Cited in Chapter 3 Innovation and Discovery: Bath and the Rise of Science. Page 47.

- Bath Naturalists: Apothecary to Zoologist. Randall, Robert. Innovation and Discovery: Bath and the Rise of Science. Pages 76–79.

- Of Canals and Quarries – The Bath Geologists. Williams, Matt. Cited in Chapter 3 Innovation and Discovery: Bath and the Rise of Science. Page 48-53.

- "QUEEN SQUARE (west side)". Images of England. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

Bibliography

- Williams, John; Diana Stoddart (1978). Bath – Some Connections With Science. Kingsmead Press.

- Wallis, Peter (Ed.) (2008). Innovation and Discovery: Bath and the Rise of Science. Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution and The William Herschel Society.