Battistello Caracciolo

Giovanni Battista Caracciolo (also called Battistello) (1578–1635) was an Italian artist and important Neapolitan follower of Caravaggio.

Battistello Caracciolo | |

|---|---|

Portrait drawing which Onofrio Giannone presumed to be of Caracciolo and published in 1773 (Museo Civico Filangieri, Naples). | |

| Born | Giovanni Battista Caracciolo December 7, 1578[lower-alpha 1] Naples |

| Died | December 23, 1635 (aged 57)[lower-alpha 2] Naples |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Francesco Imparato, Fabrizio Santafede |

| Known for | painting, fresco |

| Movement | Caravaggism |

| Spouse(s) | Beatrice de Mario |

Early life

The only substantial early source of biography is that of Bernardo de' Dominici's unreliable publication of 1742.[1] De Dominici's statements are often contradicted by documented facts and others cannot be substantiated independently.[2][lower-alpha 3] Archival documents state Caracciolo was born in Naples and baptised on 7 December 1578, as the son of Cesare Caracciolo and his wife Elena. The family lived in the parish of San Giovanni Maggiore.[2]

On 3 August 1598, at the age of twenty, Caracciolo married Beatrice de Mario. They had ten children, of whom eight survived to adulthood.[2][lower-alpha 4]

Caravaggesque phase

His initial training was said to be with Francesco Imparato and Fabrizio Santafede, but the first impulse that directed his art came from Caravaggio's sudden presence in Naples in late 1606.[3] Caravaggio had fled there after killing a man in a brawl in Rome, and he arrived at the end of September or beginning of October 1606.[4] His stay in the city lasted only about eight months, with another brief visit in 1609/1610, yet his impact on artistic life there was profound.

Caracciolo, only five years younger than Caravaggio, was among the first there to adopt the startling new style with its sombre palette, dramatic tenebrism, and sculptural figures in a shallow picture plane defined by light rather than by perspective. He is considered to be the solitary founder of the Neapolitan school of Caravaggism.[5] Among the other Neapolitan Caravaggisti were Giuseppe Ribera,[lower-alpha 5] Carlo Sellitto, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Caracciolo's pupil, Mattia Preti, then early in his career.

Caracciolo's Caravaggesque phase was fundamental to his entire career. His first contact with Caravaggio must have been around the time of the Radolovich commission, dated 6 October 1606, and the contacts continued through Caravaggio's completion of the Seven Works of Mercy during the last months of that year and early 1607. A notable result of Caravaggio's influence is Caracciolo's The Crucifixion of Christ, with its strong echoes of the Crucifixion of Saint Andrew.[6]

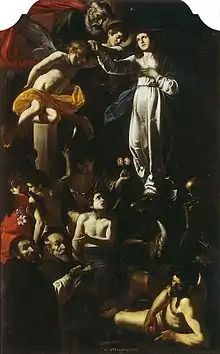

In 1607, he painted the Immaculate Conception for the Santa Maria della Stella in Naples.[7] It is considered to be his first documented Caravaggesque painting.[8]

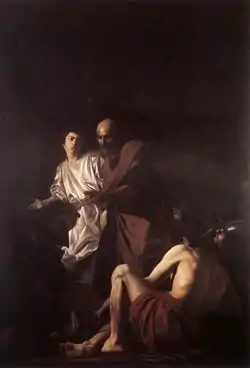

In 1612, he made a trip to Rome.[9] A work showing the influence of this visit, and especially that of Orazio Gentileschi, is the Liberation of Saint Peter (1615), painted for the Pio Monte della Misericordia,[9] to hang next to Caravaggio's Seven Works of Mercy painted for the same church.[lower-alpha 6] By this time he had become the leader of the new Neapolitan school, dividing his time between religious subjects (altarpieces and, unusually for a Caravaggist, frescos) and paintings for private patrons.

After 1618 he visited Genoa, Rome and Florence. In Rome he came under the influence of the revived Classicism of the Carracci cousins and the Emilian school, and began working towards a synthesis of their style with his own tenebrism – his Cupid, with its bravura handling of the red cloth, shows the influence of the Carracci synthesis. Back in Naples, he translated this into grandiose, wide-ranging scenes frescos including his masterpiece Christ Washing the Feet of the Disciples of 1622, painted for the Certosa di San Martino.[3] He also painted further works in the Certosa di San Martino, Santa Maria La Nova and San Diego all'Ospedaletto and these works of the late second decade of the 17th century onward, show the strong influence of Bolognese classicism he might have been exposed to in Rome.[5]

He died in Naples, in the few days between creating his last will, on 19 December 1635, and 24 December 1635, when it was opened and read.[2]

Gallery

Immaculate Conception with Saints Dominic and Francis of Paola, (1607)

Immaculate Conception with Saints Dominic and Francis of Paola, (1607) Salome. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. The painting illustrates Battistello's mastery of the visual language of Caravaggio.

Salome. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. The painting illustrates Battistello's mastery of the visual language of Caravaggio. Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (Fogg Art Museum)

Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (Fogg Art Museum) Joseph and Potiphar's wife (1618)

Joseph and Potiphar's wife (1618) Tobias and the Angel (1635)

Tobias and the Angel (1635) Christ and Caiaphas

Christ and Caiaphas Nativity in the Oratory of the Nobles

Nativity in the Oratory of the Nobles Virgin welcomes the Carmelites

Virgin welcomes the Carmelites

Notes

- Using date of baptism.

- Using date of baptism and the day before the reading of his will.

- Benedetto Croce referred to De Dominici as 'il Falsario'

- De Dominici claimed Caracciolo never married and was childless.

- On 3 May 1626, Caracciolo and Ribera are witnesses to the wedding of Giovanni Do[2]

- The Liberation is now in the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples.

References

- de' Dominici, Bernardo (1742). Vite dei Pittori, Scultori, ed Architetti Napolitani (in Italian). Napoli: Nella Stamperia del Ricciardia. pp. 273–291.

- Stoughton, Michael (April 1978). "Giovanni Battista Caracciolo: New Biographical Documents". The Burlington Magazine. 120 (901): 204, 206–213, 215. JSTOR 879164.

- Salinger, Margaretta (January 1937). "Christ and the Woman of Samaria by Caracciolo". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 32 (1): 4–6. doi:10.2307/3255289. JSTOR 3255289.

- Pacelli, Vincenzo (December 1977). "New Documents concerning Caravaggio in Naples". The Burlington Magazine. 119 (897): 819–827, 829. JSTOR 879030.

- Wittkower, Rudolf (1999). Art and Architecture in Italy, 1600–1750: The High Baroque, 1625–1675, Volume 2. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300079401.

- Pacelli, Vincenzo (August 1978). "Caracciolo Studies". The Burlington Magazine. 20 (905): 493–497, 499. JSTOR 879326.

- Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E.; Spinosa, Nicola (1992). Jusepe de Ribera, 1591–1652. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870996474. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.); Museo e gallerie nazionali di Capodimonte (1985). The Age of Caravaggio. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 106. ISBN 9780870993800.

- Spinosa, Nicola (2012). "Neapolitan Painters in Rome (1600-1630)". In Rossella Vodret (ed.). Caravaggio's Rome: 1600-1630 (paperback). Milan: Skira Editore S.p.A. p. 338. ISBN 9788857213873.

Bibliography

- Bryan, Michael (1886). Robert Edmund Graves (ed.). Dictionary of Painters and Engravers, Biographical and Critical (Volume I: A-K). York St. #4, Covent Garden, London; Original from Fogg Library, Digitized May 18, 2007: George Bell and Sons. p. 230.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Benedict Nicolson, Caravaggism in Europe, Oxford, 1979, 2e ed., dl.I, p. 74–77

- Wittkower, Rudolf (1980). Art and Architecture Italy, 1600–1750. Penguin Books. pp. 356–358.

- Ferdinando Bologna (Herausgeber) Battistello Caracciolo e il primo naturalismo a Napoli, Ausstellungskatalog Castel San Elmo, Chiesa della Certosa di San Martino, 1991/92

- Causa, Rafaello (1950). "Aggiunte al Caracciolo" [Additions to Caracciolo]. Paragone (in Italian). I (9): 42–45.

- Stefano Causa Battistello Caracciolo: L'Opera Completa 1578–1635, Neapel 2000 (Causa promovierte über Battistello an der Universität Neapel: Ricerche su Battistello Caracciolo 1994/95)

- Nicola Spinosa u.a. Tres Siglos de Oro de la Pintura Napolitana. De Battistello Caracciolo a Giacinto Gigante, Ausstellungskatalog, Museum der Schönen Künste Valencia 2003/4, Ed. Caja Duero, 2003

- Longhi, Roberto (1915). "Battistello Caracciolo". L'Arte. 18: 120–137.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battistello Caracciolo. |

- Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, which contains material on Battistello Caracciolo (see index)