Battle of Cassel (1328)

On 23 August 1328, the Battle of Cassel took place near the city of Cassel, 30 km south of Dunkirk in present-day France. Philip VI, (King of France from 1328 to 1350) fought Nicolaas Zannekin, a wealthy farmer from Lampernisse. Zannekin was the leader of a band of Flemish independence rebels. The fighting erupted over taxation and punitive edicts of the French over the Flemish. The battle was won decisively by the French. Zannekin and about 3,200 Flemish rebels were killed in the battle.

| Battle of Cassel | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Peasant revolt in Flanders 1323-1328 | |||||||

The Battle of Cassel on 23rd August 1328 by Hendrik Scheffer, 1837, Galerie des Batailles, Palace of Versailles | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Flemish peasants | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Nicolaas Zannekin † Winnoc le Fiere † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

14,500 2,500 men-at-arms 12,000 infantry | 15,000+ | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 17 knights killed | 3,185 killed | ||||||

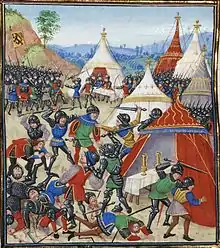

The Virgil Master, c. 1410

.jpg.webp)

Beginnings

The Count of Flanders, Louis I, was collecting taxes for Charles IV of France. Residents of the bailiwicks of Veurne, St. Winoksbergen, Belle, Kassel, Poperinge and Bourbourg united and refused to pay. The Count threatened reprisals and the people rioted, under the leadership of Nicolaas Zannekin. In 1325, Zannekin captured Nieuwpoort, Veurne and Ypres. He also captured Kortrijk and the Count of Flanders himself. Later attempts to capture Ghent and Oudenaarde failed. In February 1326, Charles IV intervened and Louis I was released and the "Peace of Arques" was agreed.

Role of the Church

On 6 April 1327, at the request of Charles IV, Pope John XXII of Avignon renewed an interdict which denied those in Flanders, other than the aristocracy and the clergy the sacraments of the church and a sacred burial. The Pope was seen as a puppet of the King. The Flemish clergy disagreed about whether or not to apply the rule. Some clergymen (who feared they would be killed by opponents of French rule) laid the papal regulation aside. Jean Laing, Dean of St. Winoksbergen, asked the clergy of his diocese to apply the regulation. Jacob Peyt, a leader of the Flemish rebels in Hondschote, tried to capture Laing and pressure the clergy to ignore the edict. The rebels' actions had some success.

Influence of the French and English royalty

Louis I feared the Flemish and Edward III would form a coalition against him. He asked Charles IV of France to intervene. Louis I departed from Ghent, (the last French stronghold in Flanders) to Paris to plead his case. On 24 January 1328 Edward III married Philippa of Hainault (1314 - 1369). Phillipa was the daughter of William I, Count of Hainaut of Avesnes and Holland, who was an ally of Charles IV.

On 1 February, Charles IV died unexpectedly. Edward III claimed the throne of France but the aristocracy favoured Philip, the son of Charles of Valois who ascended the throne as Phillip VI. The Pope urged Phillip to 'sort out' the Flemish rebels. The King re-established the rights of the Flemish aristocracy but violence erupted and some were overrun and slain by the Flemish rebels. Louis I, Count of Nevers, fled to seek help from Phillip VI.

Willem de Deken, Mayor of Bruges, an ally of the Flemish rebels, hoped the marriage of Phillipa and Edward III would assuage the English King in his dealings with Flanders. In June, de Deken travelled to England seeking support for the Flemish movement. Even though Edward III was troubled with a Scottish rebellion at the time and still held a desire to claim the French throne he was reconciled with Phillip VI and did not lend his support.[2]

Situation in the Flemish lands prior 1328

Louis I gained the upper hand against the Flemish rebels when the Bishop of Paris signed a document to the effect that anyone causing unrest would be beaten and their property confiscated with half the proceeds going to the Treasury of France. Nevertheless, the unrest continued. For example, in 1322, Louis I had forbidden cloth production outside Ieper (Ypres). The town of Poperinge ignored the monopoly and the Ieper Militia formed. Again, on 8 August 1328, in Bruges, rebels were led in uprising by Jan Breydel.

Prelude

In 1328, the Count of Flanders requested assistance from his new lord Philip VI at the latter's coronation ceremony in June. Philip saw restoring the social order in Flanders as an opportunity to strengthen his legitimacy. He wanted to march immediately against the Flemish; a French army was assembled in Arras in July. Ghent then attacked Bruges, immobilising a large part of the insurrection forces to defend the city. Counting on forcing the enemy to fight him on an open field and on terrain favourable to his cavalry, the king entrusted the marshals with the organisation of a chevauchée. The French subsequently ravaged and pillaged western Flanders as far as the gates of Bruges. Meanwhile, the bulk of the army marched on Cassel.

The battle

The engagement took place there on 23 August. The insurgents were entrenched on Mount Cassel. From there they saw their villages burning and the French army deploying. The battle of the French king consisted of 29 banners and that of the Count of Artois, 22. The memory of the Battle of the Golden Spurs in 1302, where the Flemish pikemen decimated the French chevalerie, was still well and alive. Philip VI was careful not to let his cavalry assault the enemy without thinking. Nicolaas Zannekin was the leader of the insurgents. He sent messengers to the French in order to set the day of the battle but they were received with contempt and deemed leaderless people whose only purpose was to get beat up. Without consideration for their low-born adversaries, the king's knights got rid of their armors and the French troops went to relax in their camp. The insurgents, learning of the disdain displayed by the French were infuriated. They decided to attack them immediately. The French infantry, which was caught in the middle of a nap, was overwhelmed and owed its salvation to flight. The infantrymen were found roughly grouped together the next day at Saint-Omer.

Meanwhile, the alert was given. The king, in a blue dress embroidered with golden fleurs-de-lis and wearing only a leather hat, regrouped his knights and launched a counterattack, which he led himself. The knights had lost the habit of seeing the king expose himself this way since King Louis IX. The French counter-attack forced the insurgents to form a circle, elbow to elbow, which prevented them from retreating. The tide of the battle had turned and heavy losses were inflicted on the Flemish.

Aftermath

The Flemings lost 3,185 men killed,[3][4] while the French lost 17 knights.[4] Contemporary chroniclers counted Flemish casualties as 9,000–22,000.[5] An inventory drawn up by royal French agents lists 3,185 Flemings killed at the battle, of whom 2,294 owned property worthy of confiscation, while 891 owned nothing.[6]

The French army burned down Cassel. Ypres and Bruges surrendered. King Philip designated John III of Bailleul as governor of the city of Ypres. Louis of Nevers regained control of the County of Flanders. The properties of the Flemish combatants, those who died and those who survived alike, were confiscated by envoys of the King. A third of the confiscated lands were to be given to the Count of Flanders and Robert of Cassel.

Citations

- Jan Frans Verbruggen (2002). The Battle of the Golden Spurs: (Courtrai, 11 July 1302) ; a Contribution to the History on Flanders' War of Liberation, 1297 - 1305. Boydell & Brewer. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-85115-888-4. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- James M. Murray (2005). Bruges, Cradle of Capitalism, 1280-1390. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-0-521-81921-3.

- Verbruggen 1997, p. 167.

- Kelly DeVries, Infantry Warfare in the Early Fourteenth Century, (The Boydell Press, 1996), 102.

- Kelly DeVries, Infantry Warfare in the Early Fourteenth Century, (The Boydell Press, 1996), 108.

- Tebrake 1993, p. 139.

References

- Juliaan Van Belle, Een andere Leeuw van Vlaanderen, 1985

- Leo Camerlynck and Edward De Maesschalck, In de sporen van 1302 Kortrijk Rijsel Dowaai, 2002

- Tebrake, W. (1993). A Plague of Insurrection: Popular Politics and Peasant Revolt in Flanders. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812215267.

- Verbruggen, J.F. (1997) [1954]. De Krijgskunst in West-Europa in de Middeleeuwen, IXe tot begin XIVe eeuw [The Art of Warfare in Western Europe During the Middle Ages: From the Eighth Century to 1340]. Translated by Willard, S. (2nd ed.). Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 0 85115 630 4.