Battle of Diu

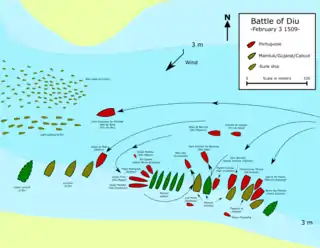

The Battle of Diu was a naval battle fought on 3 February 1509 in the Arabian Sea, in the port of Diu, India, between the Portuguese Empire and a joint fleet of the Sultan of Gujarat, the Mamlûk Burji Sultanate of Egypt, and the Zamorin of Calicut with support of the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire.[4]

| Battle of Diu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Portuguese–Mamluk Naval War | |||||||

Fort Diu, built in 1535 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Kingdom of Calicut Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Dom Francisco de Almeida |

Amir Husain Al-Kurdi Malik Ayyaz Kunjali Marakkar | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

9 naus[1] 6 caravels[1] 2 galleys and 1 brigantine 800 Portuguese soldiers[1] 400 Hindu-Nairs[2] |

10 carracks[1] 6 galleys 30 light galleys[1] 70–150 war-boats 450 Mamluks[1] 4,000-5,000 Gujaratis[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 32 dead, 300 wounded[1] |

All Mamluks killed but 22[1] All Mamluk ships sunk or captured[1] 4 Gujarati carracks captured[1] 1 300 Gujaratis dead[1] | ||||||

The Portuguese victory was critical: the great Muslim alliance was soundly defeated, easing the Portuguese strategy of controlling the Indian Ocean to route trade down the Cape of Good Hope, circumventing the traditional spice route controlled by the Arabs and the Venetians through the Red Sea and Persian Gulf. After the battle, Portugal rapidly captured key ports in the Indian Ocean including Goa, Ceylon, Malacca, and Ormuz, crippling the Mamluk Sultanate and the Gujarat Sultanate, greatly assisting the growth of the Portuguese Empire and establishing its trade dominance for more than a century.

The Battle of Diu was a battle of annihilation like the Battle of Lepanto and the Battle of Trafalgar, and one of the most important of world naval history, for it marks the beginning of European dominance over Asian seas that would last until the Second World War.[5]

Background

Just two years after Vasco da Gama reached India by sea, the Portuguese realized that the prospect of developing trade such as that which they had practiced in West Africa had become an impossibility, due to the opposition of Muslim merchant elites in the western coast of India, who incited attacks against Portuguese feitorias, ships, and agents, sabotaged Portuguese diplomatical efforts, and led the massacre of the Portuguese in Calicut in 1500.[6]

Thus, the Portuguese signed an alliance with a sworn enemy of Calicut instead, the Raja of Cochin, who invited them to establish headquarters. The Zamorin of Calicut invaded Cochin in response, but the Portuguese were able to devastate the lands and cripple the trade of Calicut, which at the time served as the main exporter of spices back to Europe, through the Red Sea. In December 1504, the Portuguese destroyed the Zamorin's yearly merchant fleet bound to Egypt, laden with spices.[7]

When King Manuel I of Portugal received news of these developments, he decided to nominate Dom Francisco de Almeida as the first viceroy of India with expressed orders not just limited to safeguarding Portuguese feitorias, but also to curb hostile Muslim shipping.[8] Dom Francisco departed from Lisbon in March 1505 with twenty ships and his 20-year-old son, Dom Lourenço, who was himself nominated capitão-mor do mar da Índia or captain-major of the sea of India.[9]

Portuguese intervention was seriously disrupting Muslim trade in the Indian Ocean, threatening Venetian interests as well, as the Portuguese became able to undersell the Venetians in the spice trade in Europe.

Unable to oppose the Portuguese, the Muslim communities of traders in India as well as the sovereign of Calicut, the Zamorin, sent envoys to Egypt pleading for aid against the Portuguese.[2]

The Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt

The Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt was, in the beginning of the 16th century, the main middleman between the spice producing regions of India, and the Venetian buyers in the Mediterranean, mainly in Alexandria, who then sold the spices in Europe at a great profit. Egypt was otherwise mostly an agrarian society with little ties to the sea.[10] Venice broke diplomatic relations with Portugal and started looking for ways to counter its intervention in the Indian Ocean, sending an ambassador to the Mamluk court and suggested that "rapid and secret remedies" be taken against the Portuguese.[11]

Light Green - Territories conquered or ceded.

Dark Green - Allies or under influence.

Yellow - Main Factorys

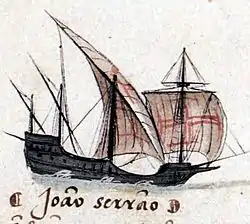

Mamluk soldiers had little expertise in naval warfare, so the Mamluk Sultan, Al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri requested Venetian support, in exchange for lowering tariffs to facilitate competition with the Portuguese.[11] Venice supplied the Mamluks with Mediterranean-type carracks and war galleys manned by Greek sailors, which Venetian shipwrights helped disassemble in Alexandria and reassemble on the Suez. The galleys could mount cannon fore and aft, but not along the gunwales because the guns would interfere with the rowers. The native ships (dhows), with their sewn wood planks, could carry only very light guns.

Command of the expedition was entrusted to a Kurdish Mamluk, former governor of Jeddah, Amir Hussain Al-Kurdi, Mirocem in Portuguese. The expedition (referred to by the Portuguese the generic term "the rumes"[12]) included not only Egyptian Mamluks, but also a large number of Turkish, Nubian and Ethiopian mercenaries as well as Venetian gunners[10] Hence, most of the coalition's artillery were archers, whom the Portuguese could easily outshoot.

The fleet left Suez in November 1505, 1100 men strong.[10] They were ordered to fortify Jeddah against a possible Portuguese attack and quell rebellions around Suakin and Mecca. They had to spend the monsoon season on the island of Kamaran and landed at Aden at the tip of the Red Sea, where they got involved in costly local politics with the Tahirid Emir, before finally crossing the Indian Ocean.[13] Hence only in September 1507 did they reach Diu, a city at the mouth of the Gulf of Khambhat, in a journey that could have taken as little as a month to complete at full sail.[14]

Diu and Malik Ayyaz

At the time of the arrival of the Portuguese in India, the Gujarati were the main long distance dealers in the Indian Ocean, and an essential intermediary in east–west trade, between Egypt and Malacca, mostly trading cloths and spices. In the 15th century, the Sultan of Gujarat nominated Malik Ayyaz, a former bowman and slave of possible Georgian or Dalmatian origin, as the governor of Diu. A cunning and pragmatic ruler, Malik Ayyaz turned the city into the main port of Gujarat (known to the Portuguese as Cambaia) and one of the main entrepôts between India and the Persian Gulf, avoiding Portuguese hostility by pursuing a policy of appeasement and even alignment – up until Hussain unexpectedly sailed into Diu.[15]

Malik Ayyaz received Hussain well, but besides the Zamorin of Calicut, no other rulers of the Indian subcontinent were forthcoming against the Portuguese, unlike what the Muslim envoys to Egypt had promised. Ayyaz himself realized the Portuguese were a formidable naval force whom he did not wish to antagonize. He could not, however, reject Hussain for fear of retaliation from the powerful Sultan of Gujarat – besides obviously Hussain's own forces now within the city. Caught in a double bind, Ayyaz decided to only cautiously support Hussain.[16]

The Battle of Chaul

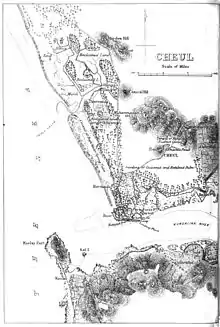

In March 1508, Hussain's and Ayyaz's fleets sailed south and clashed with Portuguese ships in a three-day naval engagement within the harbour of Chaul. The Portuguese commander was the captain-major of the seas of India, Lourenço de Almeida, tasked with overseeing the loading of allied merchant ships in that city and escort them back to Cochin.[17]

Although the Portuguese were caught off-guard (the distinctively European-like ships of Hussein were at first thought to belong to the expedition of Afonso de Albuquerque, assigned to the Arabian Coast), the battle ended as a Pyrrhic victory for the Muslims, who suffered too many losses to be able to proceed towards the Portuguese headquarters in Cochin.[18] Despite fortuitously sinking the Portuguese flagship, the rest of the Portuguese fleet escaped, while Hussain himself barely survived the encounter because of the unwilling committal of Malik Ayyaz to the battle. Hussain was left with no other choice but to return to Diu with Malik Ayyaz and prepare for a Portuguese retaliation. Hussain reported this battle back to Cairo as a great victory; however, the Mirat Sikandari, a contemporary Persian account of the Kingdom of Gujarat, details this battle as a minor skirmish.[19]

Nevertheless, among the dead was the viceroy's own son, Lourenço, whose body was never recovered, despite the best efforts of Malik Ayyaz to retrieve it for the Portuguese viceroy.

Portuguese preparations

_-_Autor_desconhecido.png.webp)

Upon hearing in Cochin of the death of his only son, Dom Francisco de Almeida was heart-stricken, and retired to his quarters for three days, unwilling to see anyone. The presence of a Mamluk fleet in India posed a grave threat to the Portuguese, but the viceroy now sought to personally exact revenge for the death of his son at the hands of Mirocem, supposedly having said that "he who ate the chick must also eat the rooster or pay for it".

Nevertheless, the monsoon was approaching, and with it the storms that inhibited all navigation in the Indian Ocean until September. Only then could the viceroy call back all available Portuguese ships for repairs in dry dock and assemble his forces in Cochin.[20]

Before they could depart though, on 6 December 1508 Afonso de Albuquerque arrived in Cannanore from the Persian Gulf with orders from the King of Portugal to replace Almeida as governor. Dom Francisco had a personal vendetta against Albuquerque, as the latter had been assigned to the Arabian Coast specifically to prevent Muslim navigation from entering or leaving the Red Sea. Yet his intentions of personally destroying the Muslim fleet in retaliation of his son's death became such a personal issue that he refused to allow his appointed successor take office. In doing so, the viceroy was in official rebellion against royal authority, and would rule Portuguese India for another year as such.[21]

On 9 December, the Portuguese fleet departed for Diu.[22]

The Armada da Índia on the move

From Cochin, the Portuguese first passed by Calicut, hoping to intercept the Zamorin's fleet, but it had already left for Diu. The armada then anchored in Baticala, to quell a dispute between its king and a local Hindu privateer allied to the Portuguese, Timoja. In Honavar, the Portuguese met with Timoja himself, who informed the viceroy of enemy movements. While there, the Portuguese galleys destroyed a fleet of raiders belonging to the Zamorin of Calicut.[22]

At Angediva, the fleet fetched freshwater and Dom Francisco met with an envoy of Malik Ayyaz, though the details of such rendezvous are unknown.[23] While there, the Portuguese were attacked by oar ships of the city of Dabul, unprovoked.

Dabul

From Angediva, the Portuguese set sail to Dabul, an important fortified port city belonging to the Sultanate of Bijapur. The captain of the galley São Miguel, Paio de Sousa, decided to investigate the harbour and put to shore, but he was ambushed by a force of about 6,000 men and was killed, along with other Portuguese. Two days later, the viceroy led his heavily armoured forces ashore and crushed the garrison stationed by the riverbank in an amphibious pincer attack. Dabul paid dearly for the act of provocation, as per the viceroy's orders the city was then razed, the surrounding riverside settlements devastated, and almost all their inhabitants killed, along with the cattle and even stray dogs in retaliation.

According to Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, the sack of Dabul gave rise to a 'curse' on the western coast of India, where one might say: "may the wrath of the franks befall you".[24]

Chaul and Bombay

From Dabul, the Portuguese called at Chaul, where Dom Francisco ordered the governor of the town to prepare a tribute to be collected on the return from Diu. Moving towards Mahim, close to Bombay, the Portuguese found the town deserted.[25]

At Bombay, Dom Francisco received a letter from Malikk Ayyaz. Doubtlessly aware of the danger facing his city, he wrote to appease the viceroy, stating that he had the prisoners and how bravely his son had fought, adding a letter from the Portuguese prisoners stating that they were well treated.[26] The viceroy answered Malik Ayyaz (referred to as Meliqueaz in Portuguese) with a respectful but menacing letter, stating his intention of revenge, that they had better join all forces and prepare to fight or he would destroy Diu:

I the Viceroy say to you, honored Meliqueaz captain of Diu, that I go with my knights to this city of yours, to take the people who were welcomed there, who in Chaul fought my people and killed a man who was called my son, and I come with hope in God of Heaven to take revenge on them and on those who assist them, and if I don't find them I will take your city, to pay for everything, and you, for the help you have done at Chaul. This I tell you, so that you are well aware that I go, as I am now on this island of Bombay, as he will tell you the one who carries this letter.[27][28]

Difficulties on the Muslim side

In the ten months between the Battle of Chaul and Diu, important developments took place on the Muslim field: Hussain took the chance to careen his ships and recovered a straggled carrack with a reinforcement of 300 men. Notwithstanding, the relationship between Hussain and Ayyaz worsened, with Hussain now plainly aware of the duplicity of Ayyaz, who had taken custody of the Portuguese prisoners at Chaul – which Hussain apparently intended "to send back to Cairo stuffed". Unable to pay the remaining of his troops, Hussain was forced to pawn his own artillery pieces to Ayyaz himself. Presumably, only either the hope of fresh reinforcements or fear of the reaction of the Sultan now prevented him from returning to Egypt.[20]

At this point, should Malik Ayyaz assist Amir Hussain, he risked his city and his life; should he choose to turn on Hussain, the Sultan might take Ayyaz' head. If Hussain stood his ground, he risked annihilation and should he retreat, risked being executed by the Sultan of Egypt.

Now in a quadruple bind, they faced the Portuguese forces.

Order of battle

Mamluk-Gujarat-Calicut fleet

Portuguese fleet

- 5 large naus: Flor de la mar (Viceroy's flagship; captain João da Nova), Espírito Santo (captain Nuno Vaz Pereira), Belém (Jorge de Melo Pereira), Rei Grande (Francisco de Távora), and Taforea Grande (Pêro Barreto de Magalhães)

- 4 smaller naus: Taforea Pequena (Garcia de Sousa), Santo António (Martim Coelho), Rei Pequeno (Manuel Teles Barreto) and Andorinha (Dom António de Noronha)

- 4 square rigged caravels: Flor da Rosa (António do Campo), Espera (Filipe Rodrigues), Conceição (Pero Cão), Santa Maria da Ajuda (Rui Soares)

- 2 caravels: Santiago (Luís Preto), – (Álvaro Pessanha)

- 2 galleys: São Miguel (Diogo Pires), São Cristóvão (Paio Rodrigues de Sousa)

- 1 brigantine: Santo António (Simão Martins)

The Battle of Diu

On 2 February 1509, the Portuguese sighted Diu from atop the crow nests. As they approached, Malik Ayyaz withdrew from the city, leaving overall command to Hussain. He ordered the oar ships to sally out and harass the Portuguese fleet before they had time to recover from the journey, but they did not pass beyond the range of the fortress' cannon. As night fell the Muslim fleet retreated into the channel, while the viceroy summoned all his captains to decide on the course of action.[25]

As day broke, the Portuguese could see that the Muslims had decided to take advantage of the harbour of Diu protected by its fort, latching their carracks and galleys together close to shore and await the Portuguese attack, thus relinquishing the initiative.[29] Portuguese forces were to be divided in four: one group to board the Mamluk carracks after a preliminary bombardment, another to attack the stationary Mamluk galleys from the flank, a 'bombardment group' that would support the rest of the fleet, and the flagship itself, which would not participate in the boarding, but would position itself in a convenient position to direct the battle and support it with its firepower. The brigantine Santo António would ensure communications.[30]

The brigantine Santo António then ran through the fleet delivering the viceroy's speech, in which he detailed the reasons for which they sought the enemy, and the rewards to be granted in case of victory: the right to the sack, knighthood to all soldiers, nobility to the knights, criminals banished from the realm would be pardoned and slaves would receive the condition of squires if they were freed within a year.[31]

Battle starts

As the wind turned by about 11:00 am, the royal banner was hoisted atop the Flor do Mar and a single shot fired, signaling the start of the battle.[31] At the general cry of Santiago! the Portuguese began their approach, with the galley São Miguel at the head of the formation, probing the channel. A general bombardment between the two forces preceded the grapple, and within the calm waters of the harbour of Diu, the Portuguese employed an innovative gunnery tactic: by firing directly at the water, the cannonballs bounced like skipping stones. A broadside from the Santo Espírito hit one of the enemy ships by the waterline, sinking it instantly.[32]

As the carracks made contact, Hussain's flagship was grappled by the Santo Espírito. When their bowcastles crossed, a group of men led by Rui Pereira jumped onto the enemy bowcastle, and before the ships were secured, already the Portuguese had stormed all the way to midship. Before the flagship was dominated though, another Mamluk carrack came to its aid, boarding the Santo Espírito from the opposite side. Hussain had strengthened his forces with a great number of Gujarati soldiers, distributed across the ships, and the heavily armoured Portuguese infantry suddenly risked being overwhelmed. Rui Pereira was killed, but at this crucial moment, the Rei Grande slammed against the free side of Hussain's flagship, delivering direly needed reinforcements, which tipped the scales in favour of the Portuguese.[33]

Up on the crow's nests, Ethiopian and Turkish bowmen proved their worth against Portuguese matchlock crews. Many of the Muslim mercenaries otherwise "fled at the first sight of the Portuguese".[34]

Hussain had expected the Portuguese to commit their entire forces to the grapple, so he kept the light oarships back within the channel, to attack the Portuguese from behind when they engaged the carracks. Comprehending the stratagem, João da Nova maneuvered the Flor do Mar to block the channel entrance and prevent the oarships from sallying out. The compact mass of oarships provided an ideal target for Portuguese gunners, who disabled many ships that then blocked the path of the ones following. Unable to break through, the Zamorin's boats turned around after a short exchange, and retreated to Calicut. Throughout the course of the battle, the Flor do Mar fired over 600 shots.[35]

Meanwhile, the faster group of galleys and caravels grappled the flank of the stationary enemy galleys, whose guns were unable to respond. An initial Portuguese assault was repelled, but a Portuguese salvo threw three of the galleys adrift.[33]

Slowly but surely, the Portuguese secured most of the carracks, half-blinded by the smoke. Hussain's flagship was overpowered and many began jumping ship. The galleys were dominated, and the shallow caravels positioned themselves between the ships and the coast, cutting down any who attempted to swim ashore.[36]

Eventually, only a single ship remained – a great carrack, larger than any other vessel in the battle, anchored too close to shore for most of the deep-draught Portuguese vessels to reach. Its reinforced hull was impervious to Portuguese cannonfire and it took a continuous bombardment from the whole fleet to finally sink it by dusk, thus marking the end of the Battle of Diu.[36]

Aftermath

The battle ended in victory for the Portuguese, with the Gujarat-Mamluk-Calicut coalition all but defeated. The Mamluks fought bravely to the very end, but were at a loss as to how to counter a naval force, the like of which they had never seen before. The Portuguese had modern ships crewed by seasoned sailors, better equipped infantry – with heavy plate armour, arquebuses, and a type of clay grenade filled with gunpowder – more cannon and gunners more proficient in an art the Mamluks could not hope to match.

After the battle, Malik Ayyaz returned the prisoners of Chaul, well dressed and fed. Dom Francisco refused to take over Diu, claiming that it would be expensive to maintain, but signed a trade agreement with Ayyaz and opened a feitoria in the city.[37] The Portuguese would later seek ardently the construction of a fortress at Diu, but the Malik managed to postpone this for as long as he was governor.

The spoils of the battle included three galleys, three carracks, 600 bronze artillery pieces, and three royal flags of the Mamlûk Sultan of Cairo that were sent to Portugal to be displayed in the Convento de Cristo, in Tomar, headquarters of the Order of Christ, former Knights Templar, which Almeida was part of.[38] The Viceroy extracted from the merchants of Diu (who funded the refittal of the Muslim fleet) a payment of 300,000 gold xerafins, 100,000 of which were distributed among the troops and 10,000 donated to the hospital of Cochin.[39]

The treatment of the Mamluk captives by the Portuguese however, was brutal. The Viceroy ordered most of them to be hanged, burned alive, or torn to pieces, tied to the mouths of cannon, in retaliation for his son's death. Commenting in the aftermath of the battle, Almeida reported to King Manuel: "As long as you may be powerful at sea, you will hold India as yours; and if you do not possess this power, little will avail you a fortress on the shore."[40] After handing over the Viceroy's post to Afonso de Albuquerque and leaving for Portugal in November 1509, Almeida was himself killed in December in a skirmish against the Khoikhoi tribe near the Cape of Good Hope, along with 70 other Portuguese – more than in the Battle of Diu. His body was buried on the beach.

Hussain survived the battle, and managed to flee Diu along with 22 other Mamluks on horseback. He returned to Cairo, and several years later was put in charge of another fleet with 3,000 men to be sent against the Portuguese, but he was murdered on the Red Sea, by his Turkish second-in-command – future Selman Reis of the Ottoman navy. The Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt would collapse to an Ottoman invasion shortly after.[38]

Of all the leading participants of the Battle of Diu, Malik Ayyaz would be the only one not to die a violent death; he died a wealthy man in his estate in 1522.[41]

Legacy

The Battle of Diu is considered as one of the most important battles in history. The author William Weir in his book 50 Battles That Changed the World, ranks this battle as the 6th most important in history, losing only to the Battle of Marathon, the Nika Rebellion, the Battle of Bunker Hill, the Battle of Arbela (Gaugamela) and the Battle of Hattin.[42] He says: "When the 15th century began, Islam seemed about ready to dominate the world. That prospect sank in the Indian Ocean off Diu."[43] The historian Rainer Daehnhardt says that this battle is compared only to the Battles of Lepanto and Trafalgar in terms of importance and legacy.[44] According to the scholar Michael Adas, this battle "established European Naval superiority in the Indian Ocean for centuries to come."[45]

See also

References

- Pissarra, José (2002). Chaul e Diu −1508 e 1509 – O Domínio do Índico Lisbon, Tribuna da História, pg.96–97

- Malabar manual by William Logan p.316, Books.Google.com

- Conquerors: How Portugal seized the Indian Ocean and forged the first Global Empire by Roger Crowley p.228

- Rogers, Clifford J. Readings on the Military Transformation of Early Modern Europe, San Francisco:Westview Press, 1995, pp. 299–333 at Angelfire.com

- Saturnino Monteiro (2011), Portuguese Sea Battles Volume I – The First World Sea Power p. 273

- Saturnino Monteiro (2011), Portuguese Sea Battles Volume I – The First World Sea Power p. 153-155

- Saturnino Monteiro (2011), Portuguese Sea Battles Volume I – The First World Sea Power p. 200-206

- Pissarra, José (2002). Chaul e Diu −1508 e 1509 – O Domínio do Índico Lisbon, Tribuna da História, pg.25

- Saturnino Monteiro (2011), Portuguese Sea Battles Volume I – The First World Sea Power p. 207

- Pissarra, José (2002). Chaul e Diu −1508 e 1509 – O Domínio do Índico Lisbon, Tribuna da História, pg.26

- Foundations of the Portuguese empire, 1415–1580 Bailey Wallys Diffie pp. 230–31 ff

- Ozbaran, Salih, "Ottomans as 'Rumes' in Portuguese sources in the sixteenth century" Portuguese Studies, Annual, 2001

- Brummett, Palmira.Ottoman Seapower and Levantine Diplomacy in the Age of Discovery, SUNY Press, New York, 1994, ISBN 0-7914-1701-8 , pp. 35, 171,22

- Porter, Venetia Ann (1992) The history and monuments of the Tahirid dynasty of the Yemen 858-923/1454-1517, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5867/ p. 100

- Pissarra, José (2002). Chaul e Diu −1508 e 1509 – O Domínio do Índico Lisbon, Tribuna da História, pg.27

- Pissarra, José (2002). Chaul e Diu −1508 e 1509 – O Domínio do Índico Lisbon, Tribuna da História, pg.32–33

- Pissarra, José (2002). Chaul e Diu −1508 e 1509 – O Domínio do Índico Lisbon, Tribuna da História, pg.33–35

- Pissarra, José (2002). Chaul e Diu −1508 e 1509 – O Domínio do Índico Lisbon, Tribuna da História, pg.61

- Bayley, Edward C. The Local Muhammadan Dynasties: Gujarat, London, 1886, 222

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 68

- Pissarra, José (2002). Chaul e Diu −1508 e 1509 – O Domínio do Índico Lisbon, Tribuna da História, pg.66

- Pissarra, José (2002). Chaul e Diu −1508 e 1509 – O Domínio do Índico Lisbon, Tribuna da História, pg.70

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 71

- "Dõde antre os indios naceo aquela maldição que dizem a ira dos frangues venha sobre ti", in Castanheda, Fernão Lopes de (1551) História do Descobrimento e Conquista da Índia pelos Portugueses, 1833 edition, Rolland, Pg 312.

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 74

- Michael Naylor Pearson, "Merchants and rulers in Gujarat: the response to the Portuguese in the sixteenth century", p. 70 University of California Press, 1976. ISBN 0-520-02809-0

- http://www.dancingwithdolphins.com.au/discovery/index.html

- http://www.ancruzeiros.pt/anchistoria-comb-1509.html Archived 3 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine (in Portuguese)

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 76

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 77–78

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 80

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 81

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 84–85

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 88

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 89–92

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 92

- Saturnino Monteiro (2011), Portuguese Sea Battles Volume I – The First World Sea Power pg. 272

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 93

- Saturnino Monteiro (2011), Portuguese Sea Battles Volume I – The First World Sea Power pg. 273

- Ghosh, Amitav The Iman and the Indian: Prose Pieces, Orient Longman, New Delhi, 2002, ISBN 81-7530-047-7, 377pp, 107

- Pissarra, 2002, pg. 57

- Weir, William (30 March 2009). 50 Battles That Changed the World: The Conflicts That Most Influenced the Course of History: Easyread Large Bold Edition. ReadHowYouWant.com. ISBN 9781442976443.

- Weir, William (3 April 2009). 50 Battles That Changed the World: The Conflicts That Most Influenced the Course of History. ReadHowYouWant.com. ISBN 9781442976566.

- Daehnhardt, Rainer (2005). Homens, Espadas e Tomates. Portugal: Zéfiro — Edições, Actividades Culturais, Unipessoal Lda. p. 34.

- Adas, Michael (1993). Islamic & European Expansion: The Forging of a Global Order. Temple University Press. ISBN 9781566390682.

Further reading

- de Camões, Luís (2002), The Lusiadas, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 254, ISBN 0-19-280151-1.

- Subrahmanyan, Sanjay (1993), The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500-1700 - A Political and Economic History, London: Longmans, ISBN 0-582-05068-5.

- Brummett, Palmira (1994), Ottoman Seapower and Levantine Diplomacy in the Age of Discovery, New York: SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1701-8.

- Kuzhippalli-Skaria, Mathew (1986), Portuguese and the Sultanate of Gujarat, 1500-1573, New Delhi: Mittal Publishers & Distr..

- Monteiro, Saturnino (2011), Portuguese Sea Battles Volume I – The First World Sea Power, Lisbon: Editora Sá da Costa.

- Kerr, Robert (1881), General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels, arranged in a systematic order, Project Gutenberg at University of Columbia.

- Pissarra, José (2002), Chaul e Diu, 1508 e 1509: O Domínio do Índico, Lisbon: Tribuna da História, ISBN 9789728563851