Battle of Grand Gulf

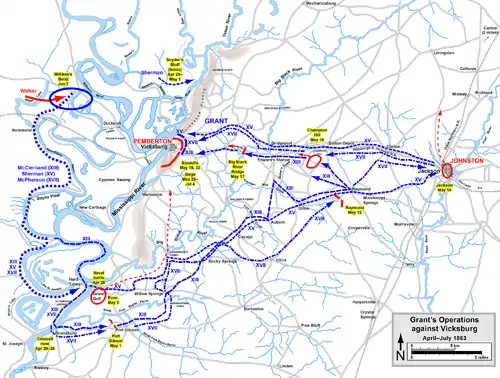

The Battle of Grand Gulf was fought on April 29, 1863, during the American Civil War. As part of Major General Ulysses S. Grant's Vicksburg campaign, seven Union Navy ironclad warships commanded by Admiral David Dixon Porter bombarded Confederate fortifications at Grand Gulf, Mississippi. One of the Confederate fortifications, named Fort Wade, was silenced, but the other, named Fort Cobun, continued firing. Due to the strong Confederate resistance, Grant and Porter decided it was not feasible to make an amphibious landing at Grand Gulf, but later landed at Bruinsburg, Mississippi, instead. After the Confederates were defeated at the Battle of Port Gibson on May 1, Grand Gulf was rendered indefensible and the fortifications were abandoned. The defenders of Grand Gulf then fought at the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16 and the Battle of Big Black River Bridge on May 17, before the start of the Siege of Vicksburg, which ended with a Confederate surrender on July 4. Today, the battlefield is preserved in Grand Gulf Military State Park, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

| Battle of Grand Gulf | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vicksburg campaign | |||||||

Battle of Grand Gulf | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| David D. Porter | John S. Bowen | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Mississippi Squadron | Bowen's Division | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

7 ironclad warships 10,000 men on transport vessels[1] | 4,200[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

75 18 killed, 57 wounded |

22 3 killed, 19 wounded | ||||||

Background

In mid-1862, Confederate field artillery had periodically harassed Union Navy vessels from Grand Gulf, Mississippi, which was located along the Mississippi River. The town was largely burned during bombardments and raids as Union troops attempted to suppress construction of earthworks around the town.[3] However, construction of Confederate batteries with heavy artillery resumed in March 1863 when troops commanded by Brigadier General John S. Bowen reoccupied the works and began to strengthen them. Confederate artillerymen from Wade's Missouri Battery, Landis' Missouri Battery, and Guibor's Missouri Battery manned cannons in the works.[4] On March 19, the sloop-of-war USS Hartford and the schooner USS Albatross tested the strength of the fortifications.[5] Most of the Confederate guns did not have the range to effectively fire at the ships, but Wade's Battery had heavier guns, enabling the unit to inflict some damage on the Hartford. Larger cannons were sent to the fortifications the next day.[4]

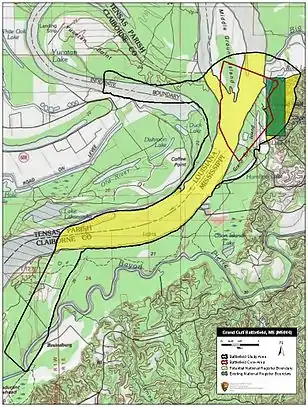

The primary works at the time of the battle were two earthen forts, Fort Cobun and Fort Wade. Atop Point of Rock, Fort Cobun was the stronger fortification due to its elevation and its parapet, 40 feet (12 m) thick. Fort Wade sat only 20 feet (6.1 m) above the river, approximately 0.75 miles (1.21 km) downstream and a quarter of mile from the water's edge. Rifle pits ran along the ridge connecting the two works.[6] Four cannons were also emplaced at Winkler's Bluff to guard the Big Black River, furnaces for heating hot shot were constructed, and a signal station was built across the Mississippi River in Louisiana.[7] Fort Cobun was manned by Battery A, 1st Louisiana Heavy Artillery; Wade's Battery and Guibor's Battery manned Fort Wade. The 3rd Missouri Infantry Regiment defended the rifle pits between the two forts and the 6th Missouri Infantry Regiment manned a second line of rifle pits. The 1st Confederate Battalion held Winkler's Bluff, and the 1st Missouri Cavalry Regiment, the 3rd Missouri Light Battery, and a unit of sharpshooters from Arkansas were positioned four miles up the Big Black River.[8] On April 16 and 22, eight Union Navy gunboats and nine transports went past the fortifications at Vicksburg and Grand Gulf; two of the transports were destroyed.[9]

Battle

Porter determined to attack the fortifications at Grand Gulf from upstream with seven casemate ironclads. At 7:00 a.m. on April 29 the ironclads left for Grand Gulf. USS Pittsburgh was in the lead, followed by USS Louisville, USS Carondelet, and USS Mound City. A second wave composed of USS Benton, USS Tuscumbia, and USS Lafayette followed. The ironclads first targeted Fort Cobun, then Pittsburgh, Louisville, Carondelet, and Mound City moved to focus on Fort Wade, while the other three focused on Fort Cobun. After passing Fort Cobun, the ships turned so that their bows pointed upstream.[10][11]

While Pittsburgh, Louisville, Carondelet, and Mound City each carried 13 guns, the positioning of the guns on the ships allowed a maximum of four guns at a time to be aimed at the Confederate fortifications, reducing the Union firepower. By 10:00 a.m., Fort Wade was knocked out of action. One of the large cannons in Fort Wade had exploded, the fortifications themselves had been severely damaged, and Colonel William F. Wade, commanding the post, had been decapitated by Union fire.[12] However, Fort Cobun fought on. A Confederate shot struck Benton, destroying the ship's wheel.[13] Around 1:00 p.m., Fort Cobun decreased its fire due to ammunition shortages. However, Porter and Grant decided not to attempt an amphibious landing against Grand Gulf due to the strength of the Confederate position. During the action, Porter had been struck in the back of his head with a shell fragment; the painful wound caused Porter to use his sword as a cane.[13] Overall, Union forces lost 18 men killed and 57 wounded, for a total of 75. Confederate losses totaled 22: three dead and 19 wounded.[13] Additionally, Tuscumbia, which was poorly built (for instance, the spikes holding the ship's iron plating on were not secured with nuts), had been badly damaged and knocked out of the fighting.[14]

Aftermath

Later that afternoon, while the angle of the sun interfered with Confederate aiming, Porter again sent his ships to Grand Gulf. This time, the navy ships served as a protecting screen for transport vessels carrying Union infantry downriver. The ships successfully passed Grand Gulf; Porter lost one man in the affair, the Confederates lost none.[15] After passing Grand Gulf, the infantrymen were unloaded at Bruinsburg, Mississippi.[9] On May 1, the troops Grant had landed fought the Battle of Port Gibson with Bowen's Confederates. Bowen's right flank was driven in, and Bowen's Confederate conducted a fighting withdrawal from the field.[16] On May 3, the Confederates abandoned the fortifications at Grand Gulf. The men of the 2nd Missouri Infantry Regiment spiked the cannons at Grand Gulf and destroyed supplies that could not be carried off.[17] Bowen's men next fought at the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16 and the Battle of Big Black River Bridge on May 17; both battles ended in Confederate defeats. Grant was then able to begin the Siege of Vicksburg on May 18. The Confederate garrison of Vicksburg surrendered on July 4, providing a major setback for the Confederate war effort.[18]

The site of the battle is preserved by Grand Gulf Military State Park. The park contains the land where forts Wade and Cobun were located, as well as an observation tower, a museum, and remains of the old town of Grand Gulf.[19] The park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.[20]

Notes

- Bearss 2007, p. 208.

- Bearss 2007, p. 210.

- Wright 1982, pp. 4–8.

- Gottschalk 1991, pp. 190–191.

- Silverstone 2006, pp. 20, 53.

- Bearss 1986, p. 307.

- Gottschalk 1991, p. 191.

- Gottschalk 1991, p. 192.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 158.

- Ballard 2004, pp. 217–218.

- Konstam 2002, pp. 24, 35–37, 40–41.

- Bearss 2007, pp. 209.

- Ballard 2004, pp. 218–219.

- Bearss 2007, pp. 208–209.

- Ballard 2004, p. 219.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 158–164.

- Gottschalk 1991, pp. 229–230.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 167–173.

- Weeks 2009, p. 102.

- "NPGallery Asset Detail". National Park Service. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

References

- Ballard, Michael B. (2004). Vicksburg, The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2893-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1986). The Campaign for Vicksburg: Grant Strikes a Fatal Blow. 2. Dayton, OH: Morningside House. ISBN 0-89029-313-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (2007) [2006]. Fields of Honor. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-0093-9.

- Gottschalk, Phil (1991). In Deadly Earnest: The Missouri Brigade. Columbia, Missouri: Missouri River Press. ISBN 0-9631136-1-5.

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Konstam, Angus (2002). Union River Ironclad 1861-65. New Vanguard. 56. Oxford, England: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-444-2.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (2006). Civil War Navies, 1855–1883. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97870-5.

- Weeks, Michael (2009). The Complete Civil War Road Trip Guide. Woodstock, Vermont: The Countryman Press. ISBN 978-0-88150-860-4.

- Wright, William C. (1982). "Archaeological Report No. 8" (PDF). The Confederate Magazine at Fort Wade Grand Gulf, Mississippi, Excavations 1980-1981. Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-22.