Battle of Liaoyang

The Battle of Liaoyang (遼陽会戦, Ryōyō-kaisen, 25 August – 3 September 1904) (Russian: Сражение при Ляояне) was the first major land battle of the Russo-Japanese War, on the outskirts of the city of Liaoyang in present-day Liaoning Province, China. The city was of great strategic importance as the major Russian military center for southern Manchuria, and a major population center on the main line on the Russian South Manchurian Railway connecting Port Arthur with Mukden. The city was fortified by the Imperial Russian Army with three lines of fortifications.[7]

| Battle of Liaoyang | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russo-Japanese War | |||||||

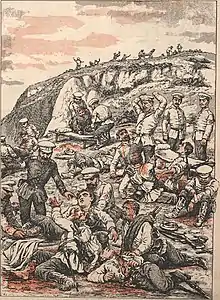

Battle of Liao Yang by Fritz Neumann | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ōyama Iwao | Aleksey Kuropatkin | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 115 battalions, 33 squadrons, 484 guns[1][2] 127,360 men | 208.5 battalions, 153 squadrons, 673 guns,[1][3] 245,300 men[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

22,922[5]

|

19,112[6]

| ||||||

Background

When the Imperial Japanese Army landed on the Liaodong Peninsula, Japanese General Ōyama Iwao divided his forces. The IJA 3rd Army under Lieutenant General Nogi Maresuke was assigned to attack the Russian naval base at Port Arthur to the south, while the IJA 1st Army, IJA 2nd Army and IJA 4th Army would converge on the city of Liaoyang. Russian General Aleksey Kuropatkin planned to counter the Japanese advance with a series of planned withdrawals, intended to trade territory for the time necessary for enough reserves to arrive from Russia to give him a decisive numerical advantage over the Japanese. However, this strategy was not in favor with the Russian Viceroy Yevgeni Ivanovich Alekseyev, who was pushing for a more aggressive stance and quick victory over Japan.

Both sides viewed Liaoyang as a site suitable for a decisive battle which would decide the outcome of the war.[7]

Preparations

At Liaoyang, Kuropatkin had a total of 14 divisions with 158,000 men, supported by 609 artillery pieces. He divided his forces into three groups.

- The Eastern Group was commanded by General Alexandr von Bilderling and consisted of the 3rd Siberian Army Corps and the 10th European Army Corps.

- The Southern Group was commanded by General Nikolai Zarubaev and consisted of the 1st Siberian Army Corps, 2nd Siberian Army Corps and 4th Siberian Army Corps, together with a total of 11 cavalry squadrons under Lieutenant General Pavel Mishchenko.

- Kuropatkin kept a reserve of 30 battalions, mostly from the 17th Siberian Army Corps.[7]

His outermost defensive line extended approximately 12 miles (19 km) to the south of the ancient walled city. With the start of the rainy season in July, the muddy terrain favored the defenders.[8]

Ōyama also divided his forces into three groups:

- IJA 1st Army under General Kuroki Tamemoto,

- IJA 2nd Army under General Oku Yasukata,

- IJA 4th Army under General Nozu Michitsura.

Ōyama had a total of eight divisions with 120,000 men and 170 artillery pieces. The overall Japanese strategy, which had been developed by General Kodama Gentarō, was to have the 2nd Army advance along the railway line, while the 1st Army converged upon the city via Motien Pass from the north. The 4th Army would be a reserve to be committed to the right of the 2nd Army towards the end of the battle.[8]

Due to a disparity in military intelligence, Kuropatkin was convinced that he was outnumbered, whereas Ōyama, with the assistance of the local Chinese population,[8] had precise knowledge of the Russian strength and deployment. However, Ōyama was concerned with his numerical inferiority, and waited to attack in hopes that a quick victory at Port Arthur would enable him to add the strength of IJA 3rd Army to his forces before yet more Russian reinforcements arrived to the north. However, after three weeks without progress at Port Arthur, Ōyama decided that he could wait no longer.

Battle

The battle began on 25 August with a Japanese artillery barrage, followed by the advance of the Japanese Imperial Guards Division under Lieutenant General Hasegawa Yoshimichi against the right flank of the 3rd Siberian Army Corps. The attack was defeated by the Russians under General Bilderling largely due to the superior weight of the Russian artillery and the Japanese took over a thousand casualties.[7]

On the night of 25 August, the IJA 2nd Division and IJA 12th Division under Major General Matsunaga Masatoshi engaged the 10th Siberian Army Corps to the east of Liaoyang. Fierce night fighting occurred around the slopes of a mountain called "Peikou", which fell to the Japanese by the evening of 26 August. Kuropatin ordered a retreat under the cover of heavy rain and fog, to the outermost defensive line surrounding Liaoyang, which he had reinforced with his reserves.[7] Also on 26 August, the advance of the IJA 2nd Army and IJA 4th Army was stalled Russian General Zarubaev before the outmost defensive line to the south.

However, on 27 August, much to the surprise of the Japanese and consternation of his commanders, Kuropatkin did not order a counterattack, but instead ordered that the outer defense perimeter be abandoned, and that all Russian forces should pull back to the second defensive line.[7] This line was approximately 7 miles (11 km) south of Liaoyang, and included several small hills which had been heavily fortified, most notably a 210-meter tall hill known to the Russians as "Cairn Hill".[8] The shorter lines were easier for the Russians to defend, but played into Ōyama’s plans to encircle and destroy the Russian Manchurian Army. Ōyama ordered Kuroki to the north, where he cut the railroad line and the Russian escape route, while Oku and Nozu were ordered to prepare for a direct frontal assault to the south.[7]

The next phase of the battle began on 30 August with a renewed Japanese offensive on all fronts. However, again due to superior artillery and their extensive fortifications, the Russians repulsed the attacks on 30 August and 31 August, causing considerable losses to the Japanese. Again to the consternation of his generals, Kuropatkin would not authorize a counter-attack. Kuropatkin continued to overestimate the size of the attacking forces, and would not agree to commit his reserve forces to the battle.[7]

On 1 September, the Japanese 2nd Army had taken Cairn Hill and approximately half of the Japanese 1st Army had crossed the Taitzu River about eight miles east of the Russian lines. Kuropatkin then decided to abandon his strong defensive line, and made an orderly retreat to the innermost of the three defensive lines surrounding Liaoyang. This enabled the Japanese forces to advance to a position where they were within range to shell the city, including its crucial railway station. This prompted Kuropatkin to at last authorize a counter-attack, with the aim of destroying the Japanese forces across the Taitzu River and securing a hill known to the Japanese as "Manjuyama", to the east of the city. Kuroki had only two complete divisions to the east of the city, and Kuropatkin decided to commit the entire 1st Siberian Army Corps and 10th Siberian Army Corps and thirteen battalions under Major General N. V. Orlov (the equivalent of five divisions) against him. However, the messenger sent by Kuropatkin with orders got lost, and Orlov’s outnumbered men panicked at the sight of the Japanese divisions.

Meanwhile, the 1st Siberian Army Corps under General Georgii Stackelberg arrived on the afternoon of 2 September, exhausted by a long march through the mud and torrential rains. When Stackelberg asked General Mishchenko for assistance from two brigades of his Cossacks, Mishchenko claimed to have orders to go elsewhere and abandoned him. The night assault of Japanese forces on Manjuyama was initially successful, but in the confusion, three Russian regiments fired upon each other, and by morning the hill was back in Japanese hands. Meanwhile, on 3 September Kuropatkin received a report from General Zarubayev on the inner defensive line that he was running short on ammunition. This report was quickly followed by a report by Stackelberg that his troops were too tired to continue the counter-attack. When a report arrived that the Japanese First Army was poised to cut off Liaoyang from the north, Kuropatkin then decided to abandon the city, and to regroup at Mukden a further 65 kilometres (40 mi) to the north. The retreat began on 3 September and was completed by 10 September.[7]

Aftermath

Despite Ōyama’s goal of encircling and annihilating the Russian forces in Manchuria at Liaoyang, Kuropatkin was able to retreat in good order as the exhausted Japanese were unable to pursue. On 7 September, Kuropatkin informed St Petersburg that he had won a great victory over the Japanese by avoiding encirclement and inflicting great losses. However, Russian War Minister Viktor Sakharov ridiculed the report.[7]

Celebrations in Tokyo were muted by the heavy casualty reports, and the knowledge that their victory was not complete as the decisive battle of the war would need to be fought elsewhere.

Officially, 5,537 Japanese and 3,611 Russian were killed, and 18,063 Japanese and 14,301 Russian wounded.[7] Soviet studies later asserted that the Russian armies suffered about 15,548 casualties (2007 killed 1448 missing, 12 093 wounded) against 23,615 total Japanese casualties [9]

Gallery

Russian forces were supported by observers in a variety of balloons, providing aerial monitoring of the unfolding battle.

Battle of Liaoyang, Russian crew of balloon handlers on the ground

Battle of Liaoyang, Russian crew of balloon handlers on the ground Battle of Liaoyang, Russian balloon anchored between missions

Battle of Liaoyang, Russian balloon anchored between missions Battle of Liaoyang, Russian observation balloon in mid-air

Battle of Liaoyang, Russian observation balloon in mid-air Battle of Liaoyang, Russian balloon, observers in the basket

Battle of Liaoyang, Russian balloon, observers in the basket Japanese General Kuroki Tamemoto and Chief of Staff Fujii Shigeta

Japanese General Kuroki Tamemoto and Chief of Staff Fujii Shigeta

Notes

- The Official history of the Russo-Japanese War / prepared by the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence Part IV p 12

- Русско-японская война 1904—1905 гг., т. 3, ч. 2. с. 257.

- Русско-японская война 1904—1905 гг., т. 3, ч. 2. с. 270.

- Свод материалов к отчету по интендантской части за время войны с Японией" стр. 398–399. табл. #30

- The Official history of the Russo-Japanese War / prepared by the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence Part IV App D

- The Official history of the Russo-Japanese War / prepared by the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence Part IV p 115

- Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War, pp. 205–208.

- Jukes, The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905, pp. 49–52.

- Russia and USSR in Wars of the XX century - Moskow, Veche, 2010 - p.32

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Liaoyang. |

- Connaughton, R. M. (1988). The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear—A Military History of the Russo-Japanese War 1904–5. London. ISBN 0-415-00906-5.

- Jukes, Geoffrey. The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. Osprey Essential Histories. (2002). ISBN 978-1-84176-446-7.

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5.