Battle of Mečkin Kamen

The Battle of Mečkin Kamen also known as 'Battle of Mechkin Kamen'[1][2] (Bulgarian: Битка при Мечкин Камен, Macedonian: Битка на Мечкин Камен) occurred on the hill now known as Mečkin Kamen ("Bear's Stone"[3]), a few kilometres south from the town of Kruševo[4] on 2–3 August 1903.

| Battle of Mečkin Kamen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

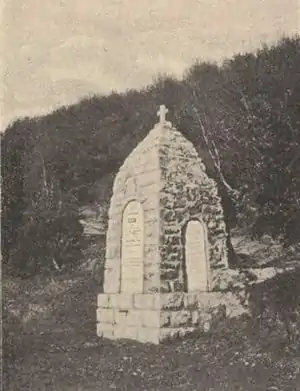

The monument on the place of the battle of Mečkin Kamen built by the Bulgarian administration during the First World War and demolished by the Serbian authorities afterwards | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 370 | 2,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 40 killed | Unknown | ||||||

It was part of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising, most of the participants were local Bulgarians peasants[5][6] with the help of bulgarophile Aromanians[7] such as Pitu Guli[8] led by the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organisation (IMARO or VMARO) against the Ottoman Empire. The leading revolutionary commanders of the local Kruševo Republic were Nikola Karev and Pitu Guli.[9]

The battle is an important event that is celebrated in Bulgaria and North Macedonia.

History

Before the battle, Pitu Guli inspected his forces and found out that 70 out of the 300 men part of his unit did not have any weapons so he let them return home.[10]

Following the takeover, and subsequent declaration of the Krusevo Republic, the surrounding areas were besieged by the Ottoman forces for an estimated 10 days, with the forces of the Macedonian Bulgarians and Vlach being outnumbered and overrun. Following the battles of Sliva and Meckin Kamen, large parts of the Vlach areas and villages were destroyed while 'the Bulgarian quarter' was mostly spared.[11]

Revolutionary Pitu Guli and most of his men were killed at the battle of Mečkin Kamen while Nikola Karev managed to break through the Turkish lines and escaped back to Bulgaria.[12]

The Turkish forces entered the town of Kruševo on the 12th August 1903.[13]

Legend

There is a legend behind the name of the hill. A long time ago in a small suburb besides the orchids lived a number of brothers. They occupied their time with agriculture and livestock. One day the brothers were returning from the hill when they were confronted by a big bear. The brave people of Kruševo were not frightened, instead they attacked the bear. The bear rolled a rock down the hill towards the brothers, but then they killed the bear with a couple of strikes from their axes. The rock which was rolled by the bear was known as Mečkin Kamen (Bear's Rock) by the people.

Legacy

A monument exists today on Mečkin Kamen where Pitu Guli was killed.[14] There is a Second World war memorial by Dimo Todorovski at the same site.

References

- The Macedonian Times, Issues 63-74, Republic of Macedonia, MI-AN, pg 5, pg 23, pg 36

- Višinski, Boris (1973). The Epic of Ilinden. SR Macedonia: Macedonian Review Editions. pp. 241, 242.

- Леандра Петрова, Димо Тодоровски (1980). Димо Тодоровски. Македонска книга. p. 49.

- MacDermott, Mercia (1978). Freedom Or Death, the Life of Gotsé Delchev. Journeyman Press. p. 378. ISBN 9780904526325.

- The "Adrianopolitan" part of the organization's name indicates that its agenda concerned not only Macedonia but also Thrace — a region whose Bulgarian population is by no means claimed by Macedonian nationalists today. In fact, as the organization's initial name ("Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees") shows, it had a Bulgarian national character: the revolutionary leaders were quite often teachers from the Bulgarian schools in Macedonia. This was the case of founders of the organization... Their organization was popularly seen in the local context as "the Bulgarian committee(s). Tchavdar Marinov, Famous Macedonia, the Land of Alexander: Macedonian identity at the crossroads of Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian nationalism in Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies with Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov as ed., BRILL, 2013, ISBN 900425076X, pp. 273-330.

- The political and military leaders of the Slavs of Macedonia at the turn of the century seem not to have heard the call for a separate Macedonian national identity; they continued to identify themselves in a national sense as Bulgarians rather than Macedonians.[...] (They) never seem to have doubted "the predominantly Bulgarian character of the population of Macedonia". "The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world", Princeton University Press, Danforth, Loring M. 1997, ISBN 0691043566, p. 64.

- Autonomy for Macedonia and the vilayet of Adrianople (southern Thrace) became the key demand for a generation of Slavic activists. In October 1893, a group of them founded the Bulgarian Macedono-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Committee in Salonica...It engaged in creating a network of secretive committees and armed guerrillas in the two regions as well as in Bulgaria, where an ever-growing and politically influential Macedonian and Thracian diaspora resided. Heavily influenced by the ideas of early socialism and anarchism, the IMARO activists saw the future autonomous Macedonia as a multinational polity, and did not pursue the self-determination of Macedonian Slavs as a separate ethnicity. Therefore, Macedonian (and also Adrianopolitan) was an umbrella term covering Bulgarians, Turks, Greeks, Vlachs, Albanians, Serbs, Jews, and so on. While this message was taken aboard by many Vlachs as well as some Patriarchist Slavs, it failed to impress other groups for whom the IMARO remained the Bulgarian Committee.' Historical Dictionary of Republic of Macedonia, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, Introduction.

- Brown, K. (2003) The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation (Princeton: Princeton University Press) ISBN 0-691-09995-2

- Brown, Keith S. (2013). Loyal Unto Death: Trust and Terror in Revolutionary Macedonia. Indiana University Press. p. 192. ISBN 9780253008350.

- Stojčev, Vanče (2004). Military History of Macedonia. Military Academy "General Mihailo Apostolski". p. 321.

- Bechev, Dimitar (2019). Historical Dictionary of North Macedonia. London: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 174. ISBN 9781538119617.

- Assa, Aaron (1994). Macedonia and the Jewish People. Macedonian Review. p. 80.

- Apostolski, Mihailo (1969). From the Past of the Macedonian People. Skopje Radio and Television. p. 173.

- "7 Best Places to Visit in Macedonia Before You Die". Insider Monkey. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

Sources

- MI-AN Publishing, Skopje 1998, Macedonia Yesterday And Today.