Kruševo Republic

The Kruševo Republic (Aromanian: Republica di Crushuva; Bulgarian[1][2] and Macedonian: [3][4] Крушевска Република, romanized: Kruševska Republika) was a short-lived political entity proclaimed in 1903 by rebels from the Secret Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) in Kruševo during the anti-Ottoman Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising.[5] According to subsequent Bulgarian and followed later Macedonian narratives, it was one of the first modern-day republics in the Balkans.

Republic of Kruševo Крушевска Република Republica di Crushuva | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1903–1903 | |||||||||

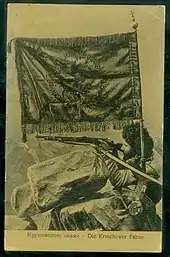

Flag | |||||||||

| Capital | Kruševo | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1903 | Nikola Karev | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1903 | Vangel Dinu | ||||||||

| Historical era | Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising | ||||||||

• Established | 3 August 1903 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 13 August 1903 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

History

On 3 August 1903, rebels captured the town of Kruševo in the Manastir Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire (present-day North Macedonia) and established a revolutionary government. The entity existed only for 10 days: from August 3 to August 13, and was headed by Nikola Karev.[8] He was a strong leftist, rejecting the nationalism of the ethnic minorities and favouring alliances with ordinary Muslims against the Sultanate, as well as supporting the idea of a Balkan Federation.[9]

Amongst the various ethnoreligious groups (millets) in Kruševo, a Republican Council was elected with 60 members – 20 representatives from three groups: Aromanians, Greek Patriarchists and Bulgarian Exarchists.[10][11][12][13] The Council also elected an executive body—the Provisional Government—with six members (2 from each mentioned group),[14] whose duty was to promote law and order and manage supplies, finances, and medical care. The presumable "Kruševo Manifesto" was published in the first days after the proclamation. Written by Nikola Kirov, it outlined the goals of the uprising, calling upon the Muslim population to join forces with the provisional government in the struggle against Ottoman tyranny, to attain freedom and independence.[15] Both Nikola Kirov and Nikola Karev were members of the Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party, from where they derived these leftist ideas.[16]

However, an ethnic identification problem arose. Karev called all the members of the local Council "brother Bulgarians", while the IMRO insurgents flew Bulgarian flags, killed five Greek Patriarchists, accused of being Ottoman spies, and subsequently assaulted the local Turk and Albanian Muslims. As long as the town was controlled by the Bulgarian komitadjis, the Patriarchist majority was suspected and terrorized.[18] Except for Exarchist Aromanians,[19] who were Bulgarophiles,[20][21] (as Pitu Guli and his family), most members of the other ethnoreligious communities dismissed the IMRO as pro-Bulgarian.[22][23]

Initially surprised by the uprising, the Ottoman government took extraordinary military measures to suppress it. Pitu Guli's band (cheta) tried to defend the town from Ottoman troops coming from Bitola. The whole band and their leader (voivode) perished. After fierce battles near Mečkin Kamen, the Ottomans managed to destroy the Kruševo Republic, committing atrocities against the rebel forces and the local population.[24] As a result of the gunnery, the town was set partially ablaze.[25] After the plundering of the town by the Turkish troops and the Albanian bashi-bazouks, the Ottoman authorities circulated a declaration for the inhabitants of Kruševo to sign, stating that the Bulgarian komitadjis had committed the atrocities and looted the town. A few citizens did sign it under administrative pressure.[26]

Celebration

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of North Macedonia |

|

| Chronological |

|

| Topical |

| Related |

|

|

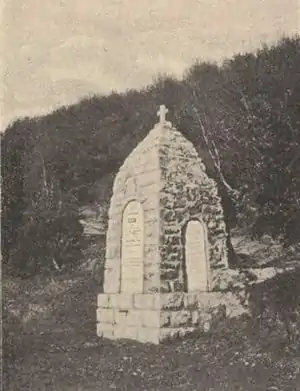

The celebration of the events in Kruševo began during the First World War, when the area, then called Southern Serbia, was occupied by Bulgaria. Naum Tomalevski, who was appointed a mayor of Kruševo, organized the nationwide celebration of the 15th anniversary of the Ilinden uprising.[27] On the place of the Battle of Mečkin Kamen, a monument and a memorial-fountain were built. After the war, they were destroyed by the Serbian authorities, which continued implementing a policy of forcible serbianization. The tradition of celebrating these events was restored during World War II in the region when it was called already Vardarska Banovina and was officially annexed by Bulgaria.[28]

Meanwhile, the newly organized pro-Yugoslav Macedonian communist partisans developed the idea of some kind of socialist continuity between their struggle and the struggle of the insurgents in Kruševo.[29] Moreover, they exhorted the population to struggle for "free Macedonia" and against the "fascist Bulgarian occupiers". After the war, the story continued in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia, where the Kruševo Republic was included in its historical narrative. The new Communist authorities successfully wiped out the remaining Bulgarophile sentiments.[30] As part of the efforts to prove the continuity of the new Macedonian nation and the former insurgents, they claimed the IMRO-activists had been consciously Macedonian in identity.[31] The establishment of the short-lived entity is seen today in North Macedonia as a prelude to the independence of the modern Macedonian state.[32]

The "Ilinden Uprising Museum" was founded in 1953 on the 50th anniversary of the Krusevo Republic. It was located in the empty house of the Tomalevski family, where the Republic was proclaimed, though the family had long since emigrated to Bulgaria. In 1974 an enormous monument was built on the hill above Kruševo, which marked the feat of the revolutionaries and the ASNOM. In the area, there is another monument called Mečkin Kamen.[33]

Modern references

Nikola Kirov's writings, which are among the most known primary sources on the rebellion, mention Bulgarians, Vlachs (Aromanians), and Greeks (sic: Grecomans), who participated in the events in Krushevo.[34] Although post-World War II Yugoslav Communist historians objected to Kirov's classification of Krusevo's Slavic population as Bulgarian, they quickly adopted everything else in his narrative of the events in 1903 as definitive.[35] However, during the Informbiro period, the name of insurgents leader Nikola Karev was scrapped from the Macedonian anthem,[36] as he and his brothers were suspected of being bulgarophile elements.[37] Some modern Macedonian historians such as Blaže Ristovski have recognized, that the entity, nowadays a symbol of the Macedonian statehood, was composed of people who identified themselves as "Greeks", "Vlachs" ("Aromanians"), and "Bulgarians".[38][39][40] In the early 20th century, Kruševo was populated by a Slavic population, Aromanians and Orthodox Albanians with town inhabitants being ethnoreligiously split among various Ottoman millets, with Greek Patriarchists being the largest community, followed by Bulgarian Exarchists and the Ullah Millet for the Aromanians.[41][42][43] According to the ethnographer Vasil Kanchov's statistics based on linguistic affinity, at that time the town's inhabitants counted: 4,950 Bulgarians, 4,000 Vlachs (Aromanians) and 400 Orthodox Albanians.[44] When the anthropologist Keith Brown visited Kruševo on the eve of the 21st century, he discovered that the local Aromanian dialect still has no way to distinguish "Macedonian" and "Bulgarian", and uses the designation Vrgari, i.e. "Bulgarians", for both ethnic groups.[45] This upsets the younger generations of Macedonians in the town, since being Bulgarian has remained a stigma since Yugoslav times.[46][47][48]

Gallery

The monument of the Battle of Mečkin Kamen built by the Bulgarian authorities during the First World War.

The monument of the Battle of Mečkin Kamen built by the Bulgarian authorities during the First World War. Celebration of the 15th anniversary of the events in Krushevo in 1918 during the Bulgarian occupation.

Celebration of the 15th anniversary of the events in Krushevo in 1918 during the Bulgarian occupation. Old comitadji, celebrating Ilinden Uprising in Krusevo in 1943, during the Bulgarian annexation.

Old comitadji, celebrating Ilinden Uprising in Krusevo in 1943, during the Bulgarian annexation. The monument of the Battle of Sliva, near Krusevo.

The monument of the Battle of Sliva, near Krusevo. Ilinden (memorial) built by the Yugoslav authorities in 1974.

Ilinden (memorial) built by the Yugoslav authorities in 1974. Celebration of Ilinden on August 2, 2011 on Mechkin Kamen, Republic of Macedonia.

Celebration of Ilinden on August 2, 2011 on Mechkin Kamen, Republic of Macedonia.

See also

References

- "The Macedonian Revolutionary Organization used the Bulgarian standard language in all its programmatic statements and its correspondence was solely in the Bulgarian language. Nearly all of its leaders were Bulgarian teachers or Bulgarian officers, and received financial and military help from Bulgaria. After 1944 all the literature of Macedonian writers, memoirs of Macedonian leaders, and important documents had to be translated from Bulgarian into the newly invented Macedonian." For more see: Bernard A. Cook ed., Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2, Taylor & Francis, 2001, ISBN 0815340583, p. 808.

- "The obviously plagiarized historical argument of the Macedonian nationalists for a separate Macedonian ethnicity could be supported only by linguistic reality, and that worked against them until the 1940s. Until a modern Macedonian literary language was mandated by the communist-led partisan movement from Macedonia in 1944, most outside observers and linguists agreed with the Bulgarians in considering the vernacular spoken by the Macedonian Slavs as a western dialect of Bulgarian". Dennis P. Hupchick, Conflict and Chaos in Eastern Europe, Palgrave Macmillan, 1995, ISBN 0312121164, p. 143.

- Kirov-Majski wrote on the history of the IMRO and authored in 1923 the play "Ilinden" in the dialect of his native town (Kruševo). The play is the only direct source containing the Kruševo Manifesto, the rebels' programmatic address to the neighbouring Muslim villages, which is regularly quoted by modern Macedonian history and textbooks. Dimitar Bechev Historical Dictionary of North Macedonia, Rowman & Littlefield, 2019, ISBN 1538119625, p. 166.

- Kruševo Manifesto's historical authenticity is disputed. There is no original preserved and this fragment from Kirov's play from 1923 was proclaimed to be completely authentic by the Communist partisans in Vardar Macedonia during the Second World War. It was published by them as a separate Proclamation of the headquarters of the Krusevo rebels. For more see: Keith Brown, The past in question: modern Macedonia and the uncertainties of nation, Princeton University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-691-09995-2, p. 230.

- There was even an attempt to form a kind of revolutionary government led by the socialist Nikola Karev. The Krushevo manifesto was declared, assuring the population that the uprising was against the Sultan and not against Muslims in general, and that all peoples would be included. As the population of Krushevo was two thirds hellenised "Vlachs" (Aromanians) and Patriarchist Slavs, this was a wise move. Despite these promises the insurgent flew Bulgarian flags everywhere and in many places the uprising did entail attacks on Muslim Turks and Albanians who themselves organised for self-defence." Who are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1995, ISBN 1850652384, p. 57.

- Keith Brown, The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation, Princeton University Press, 2018, ISBN 0691188432, p. 71.

- Dragi Ǵorǵiev, Lili Blagaduša, Documents Turcs sur l'insurrection de St. Élie provenants du fonds d'archives du Sultan "Yild'z", Arhiv na Makedonija, 1997, p. 131.

- Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. 114.

- "It would nevertheless be far-fetched to see in the Macedonian socialism an expression of national ideology... It is difficult to place the local socialist articulation of the national and social question of the late 19th and early 20th centuries entirely under the categories of today's Macedonian and Bulgarian nationalism. If Bulgarian historians today condemn the "national-nihilistic" positions of that group, their Macedonian colleagues seem frustrated by the fact that it was not "conscious" enough of Macedonians' distinct ethnic character." Entangled Histories of the Balkans – Volume Two, Roumen Daskalov, Diana Mishkova, BRILL, 2013, ISBN 9004261915, p. 503.

- Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900–1996, Chris Kostov, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 71.

- Fieldwork Dilemmas: Anthropologists in Postsocialist States, Editors Hermine G. De Soto, Nora Dudwick, University of Wisconsin Press, 2000, ISBN 0299163741, pp. 36–37.

- Tanner, Arno (2004). The Forgotten Minorities of Eastern Europe: The history and today of selected ethnic groups in five countries. East-West Books. p. 215. ISBN 952-91-6808-X.

- The past in question: modern Macedonia and the uncertainties of nation, Keith Brown, Publisher Princeton University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-691-09995-2, pp. 81–82.

- We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe, Diana Mishkova, Central European University Press, 2009, SBN 9639776289, p. 124.

- Pål Kolstø, Myths and boundaries in south-eastern Europe, Hurst & Co., ISBN 1850657726, p. 284.

- Mercia MacDermottFreedom Or Death: The Life of Gotsé Delchev, Pluto Press, 1978, ISBN 0904526321, p.386.

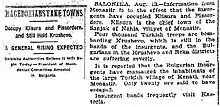

- In a series of reports, the newspaper's correspondents informed the readers: On August 7, The Governor's Palace at Krushevo Blown Up. Fifty Turks Killed. The Porte to Adopt "Measures of Extreme Severity"; On Aug. 8, Bulgarian bands have occupied Krushevo and are besieging other villages near Monastir; On August 14, Four thousand Turkish troops are bombarding the town, and the Bulgarians there are suffering severely; On August 15, Ruthless Massacres by Both Sides Reported. All the Turks in Krushevo Slain, Mussulmans Said to Have Killed Nearly All the Christians in Kitshevo; On August 22, Three Hundred Bulgarians Slain in Krushevo, Besides Innocent Greeks and Vlachs. 8,000 People Starving.

- Michael Palairet, Macedonia: A Voyage through History (Vol. 2), Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, ISBN 1443888494, p. 149.

- Aromanian consciousness was not developed until the late 19th century, and was influenced by the rise of Romanian national movement. As result, wealthy, urbanized Ottoman Vlachs were culturally hellenised during 17-19th century and some of them bulgarized during the late 19th and early 20th. century. Raymond Detrez, 2014, Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 1442241802, p. 520.

- Коста Църнушанов, Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него, Университетско изд. "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1992, стр. 132.

- Тодор Балкански, Даниела Андрей, Големите власи сред българите, Знак 94, ISBN 9548709082, 1996, стр. 60-70.

- Andrew Rossos, Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History, Hoover Press, 2013, ISBN 081794883X,p. 105.

- Philip Jowett, Armies of the Balkan Wars 1912–13: The priming charge for the Great War, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012, ISBN 184908419X, p. 21.

- P. H. Liotta, Dismembering the State: The Death of Yugoslavia and why it Matters, Lexington Books, 2001, ISBN 0739102125, p. 293.

- John Phillips, Macedonia: Warlords and Rebels in the Balkans, I.B.Tauris, 2004, ISBN 0857714511, p. 27.

- Feliks Gross, Violence in politics: Terror and political assassination in Eastern Europe and Russia, Volume 13 of Studies in the Social Sciences, Walter de Gruyter, 2018, ISBN 3111382443, p. 128.

- Цочо В. Билярски, Из рапортите на Наум Томалевски до ЦК на ВМРО за мисията му в Западна Европа; 2010-04-24, Сите българи заедно.

- Bulgaria During the Second World War, Marshall Lee Miller, Stanford University Press, 1975, ISBN 0804708703, p. 128.

- Roumen Daskalov, Diana Mishkova, Entangled Histories of the Balkans – Volume Two: Transfers of Political Ideologies and Institutions, BRILL, 2013, ISBN 9004261915, p. 534.

- Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996, Chris Kostov, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 84.

- James Frusetta "Common Heroes, Divided Claims: IMRO Between Macedonia and Bulgaria". Central European University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-963-9241-82-4, pp. 110–115.

- The political and military leaders of the Slavs of Macedonia at the turn of the century seem not to have heard the call for a separate Macedonian national identity; they continued to identify themselves in a national sense as Bulgarians rather than Macedonians.[...] (They) never seem to have doubted "the predominantly Bulgarian character of the population of Macedonia". "The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world", Princeton University Press, Danforth, Loring M. 1997, ISBN 0691043566, p. 64.

- Meckin Kamen monument - Travel to Macedonia.

- For more see: Chris Kostov, Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996, Volume 7 of Nationalisms across the globe, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 71.

- Keith Brown, The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation, Princeton University Press, 2003, ISBN 0691099952, p. 81.

- Pål Kolstø, Strategies of Symbolic Nation-building in South Eastern Europe, Routledge, 2016, ISBN 1317049365, p. 188.

- Keith Brown, The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation, Princeton University Press, 2018 ISBN 0691188432, p. 191.

- "Беше наполно прав и Мисирков во своjата фундаментална критика за Востанието и неговите раководители. Неговите укажуваньа се покажаа наполно точни во послешната практика. На пр., во ослободеното Крушево се формира градска управа составена од "Бугари", Власи и Гркомани, па во зачуваните писмени акти не фигурираат токму Македонци(!)..." Блаже Ристовски, "Столетиjа на македонската свест", Скопје, Култура, 2001, стр. 458.

- "We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe" Diana Mishkova, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, p. 124: Ristovski regrets the fact that the "government" of the "republic" (nowadays held to be a symbol of Macedonian statehood) was actually composed of two "Greeks", two "Bulgarians" and one "Romanian". cf. Ristovski (2001).

- "The IMRO activists saw the future autonomous Macedonia as a multinational polity, and did not pursue the self-determination of Macedonian Slavs as a separate ethnicity. Therefore, Macedonian was an umbrella term covering Bulgarians, Turks, Greeks, Vlachs, Albanians, Serbs, Jews, and so on." Historical Dictionary of Macedonia, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, Introduction.

- Zografski, Dančo (1986). Odbrani dela vo šest knigi: Makedonskoto nacionalno dviženje. Naša kniga. p. 21. "Населението на Крушево во време на востанието гб сочинуваат Македонци, Власи и Албанци. Први се доселиле во него Власите кон втората половина од XVIII век, односно по познатите грчки востанија од 1769 година..."

- William Miller, Ottoman Empire and Its Successors 1801–1927: With an Appendix, 1927–1936, Cambridge University Press, 2013, ISBN 1107686598, p. 446.

- Thede Kahl, The Ethnicity of Aromanians after 1990: the Identity of a Minority that Behaves like a Majority, Ethnologia Balkanica, Vol. 6 (2002), LIT Verlag Münster, p. 148.

- Васил Кънчов. „Македония. Етнография и статистика“. София, 1900, стр.240 (Kanchov, Vasil. Macedonia — ethnography and statistics Sofia, 1900, p. 39-53).

- Chris Kostov, Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 71.

- After WWII in Macedonia the past was systematically falsified to conceal the fact that many prominent ‘Macedonians’ had supposed themselves to be Bulgarians, and generations of students were taught the pseudo-history of the Macedonian nation. The mass media and education were the key to this process of national acculturation, speaking to people in a language that they came to regard as their Macedonian mothertongue, even if it was perfectly understood in Sofia. For more see: Michael L. Benson, Yugoslavia: A Concise History, Edition 2, Springer, 2003, ISBN 1403997209, p. 89.

- Yugoslav Communists recognized the existence of a Macedonian nationality during WWII to quiet fears of the Macedonian population that a communist Yugoslavia would continue to follow the former Yugoslav policy of forced Serbianization. Hence, for them to recognize the inhabitants of Macedonia as Bulgarians would be tantamount to admitting that they should be part of the Bulgarian state. For that the Yugoslav Communists were most anxious to mold Macedonian history to fit their conception of Macedonian consciousness. The treatment of Macedonian history in Communist Yugoslavia had the same primary goal as the creation of the Macedonian language: to de-Bulgarize the Macedonian Slavs and to create a separate national consciousness that would inspire identification with Yugoslavia. For more see: Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.

- In Macedonia, post-WWII generations grew up "overdosed" with strong anti-Bulgarian sentiment, leading to the creation of mainly negative stereotypes for Bulgaria and its nation. The anti-Bulgariansim (or Bulgarophobia) increased almost to the level of state ideology during the ideological monopoly of the League of Communists of Macedonia, and still continues to do so today, although with less ferocity... However, it is more important to say openly that a great deal of these anti-Bulgarian sentiments result from the need to distinguish between the Bulgarian and the Macedonian nations. Macedonia could confirm itself as a state with its own past, present and future only through differentiating itself from Bulgaria. For more see: Mirjana Maleska. With the eyes of the "other"(about Macedonian-Bulgarian relations and the Macedonian national identity). In New Balkan Politics, Issue 6, pp. 9-11. Peace and Democracy Center: "Ian Collins", Skopje, Macedonia, 2003. ISSN 1409-9454.