Battle of Muye

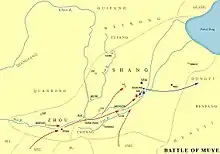

The Battle of Muye or Battle of Mu (c. 1046 BC)[1][lower-alpha 1] was a battle fought in ancient China between the rebel Zhou state and the reigning Shang dynasty. The Zhou army, led by Ji Fa, defeated the defending army of King Zhou of Shang at Muye and captured the Shang capital Yin, ending the Shang dynasty. The Zhou victory led to the establishment of the Zhou dynasty, and was used through history as a justified example of the doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven.

| Battle of Muye | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Shang | Zhou and its allies | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| King Zhou of Shang | Jiang Ziya | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Historical Records: 530,000 Shang troops (not all loyal) 170,000 slaves (who later defected) ~Total 700,000 men Modern Estimates: 50,000-70,000 Shang Troops Many slaves |

Historical Records: 300 Zhou chariots 3,700 rebel principalities chariots 3,000 Zhou elite 45,000 Zhou footmen | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| All loyal Shang soldiers were slaughtered | Relatively minor | ||||||

| Battle of Muye | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 牧野之戰 | ||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Mùyě zhī Zhàn | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Background

By the 12th century BC, Shang influence extended west to the Wei River valley, a region that was occupied by clans known as the Zhou. King Wen of Zhou, the ruler of the Zhou, who was a Shang vassal, was given the title "Count of the West" by the King Di Xin of Shang (King Zhòu). Di Xin used King Wen to guard his rear while he was involved in a south-eastern campaign.

Eventually Di Xin, fearing King Wen's growing power, imprisoned him. Although Wen was later released, the tension between Shang and Zhou grew. Wen prepared his army, and conquered a few smaller states which were loyal to Shang, slowly weakening Shang's allies. However, King Wen died in 1050 BC before Zhou's actual offensive against Shang.

Di Xin paid very little attention to these, as he viewed himself as the rightful ruler of China, a position appointed by the heavens, or perhaps because he was becoming engrossed with his personal life with his beautiful consort Daji, to the exclusion of all else.

King Wen's son King Wu of Zhou led the Zhou in a revolt a few years later. The reason for this delay was because King Wu believed that the "heavenly order" to conquer Shang had not been given, as well as the advice of Jiang Ziya to wait for the right opportunity.

Chinese civilians greatly supported King Wu's rebellion. In legend, Di Xin, initially, had been a good ruler. But after he married Daji, he became a ruthless ruler. Many called for the end of the Shang dynasty.

Battle

With Jiang Ziya as the strategist, King Wu of Zhou led an army of about 50,000. Di Xin's army was at war in the east, but he still had about 530,000 men to defend the capital city of Yin. But to further secure his victory, he gave weapons to about 170,000 slaves to protect the capital. These slaves did not want to fight for the corrupt Shang dynasty, and defected to the Zhou army instead.

This event greatly lowered the morale of the Shang troops. When engaged, many Shang soldiers did not fight and held their spears upside down, as a sign that they no longer wanted to fight for the corrupt Shang. Some Shang soldiers joined the Zhou outright.

Still, many loyal Shang troops fought on, and a very bloody battle followed, which is described in the Shijing (poem #236), as translated by James Legge:

- The troops of Yin-shang,

- Were collected like a forest,

- And marshalled in the wilderness of Mu.

- ...

- 'God is with you, ' [said Shang-fu to the king],

- 'Have no doubts in your heart. '

- The wilderness of Mu spread out extensive ;

- Bright shone the chariots of sandal ;

- The teams of bays, black-maned and white-bellied, galloped along ;

- The grand-master Shang-fu,

- Was like an eagle on the wing,

- Assisting king Wu,

- Who at one onset smote the great Shang.

- That morning's encounter was followed by a clear bright [day].

The Zhou troops were much better trained, and their morale was high. In one of the chariot charges, King Wu broke through the Shang's defense line. Di Xin was forced to flee to his palace, and the remaining Shang troops fell into further chaos. The Zhou were victorious and showed little mercy to the defeated Shang, shedding enough blood "to float a log".

Aftermath

After the battle, Di Xin adorned himself with many valuable jewels then lit a fire and burned himself to death in his palace on the Deer Terrace Pavilion. King Wu killed Daji after he found her with the order to execute her given by Jiang Ziya. Shang officials were released without charge with some later working as Zhou officials. The imperial grain store was opened immediately after the battle to feed the starving population. The battle marked the end of the Shang dynasty and the beginning of the Zhou dynasty.

Dating

Although the day and month on which the Battle of Muye was fought are certain, there is doubt about the year.[2] Prior to the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project, previous chronologies had proposed at least 44 different dates for this event, ranging from 1130 to 1018 BC.[3][4] The most popular have been 1122 BC, calculated by the Han dynasty astronomer Liu Xin, and 1027 BC, deduced from a statement in the "old text" Bamboo Annals that the Western Zhou (whose end point is known to be 770 BC) had lasted 257 years.[5][6]

A few documents relate astronomical observations to this event:

- A quotation in the Book of Han from the lost Wǔchéng 武成 chapter of the Book of Documents appears to describe a lunar eclipse just before the beginning of King Wu's campaign. This date, and the date of his victory, are given as months and sexagenary days.[7][8]

- A passage in the Guoyu gives the positions of the Sun, Moon, Jupiter and two stars on the day King Wu attacked the Shang.[6][8]

- The "current text" Bamboo Annals mentions conjunctions of all five planets occurring before and after the Zhou conquest. Han-period texts mention the first conjunction as occurring in the 32nd year of the reign of the last king. Such events are rare, but all five planets did gather on 28 May 1059 BC and again on 26 September 1019 BC. Although the recorded positions in the sky of these two events are the reverse of what occurred, they could not have been retrospectively calculated at the time the account first appears.[9]

The strategy adopted by the Project was to use archeological investigation to narrow the range of dates that would need to be compared with the astronomical data. Although no archaeological traces of King Wu's campaign have been found, the pre-conquest Zhou capital at Fengxi in Shaanxi has been excavated and strata at the site have been identified with the pre-dynastic Zhou. Radiocarbon dating of samples from the site as well as at late Yinxu and early Zhou capitals, using the wiggle matching technique, yielded a date for the conquest between 1050 and 1020 BC. The only date within that range matching all the astronomical data is 20 January 1046 BC. This date had previously been proposed by David Pankenier, who had matched the above passages from the classics with the same astronomical events, but here it resulted from a thorough consideration of a broader range of evidence.[10][11][12]

Other scholars have raised several criticisms of this process. The connection between the layers at the archaeological sites and the conquest is uncertain.[13] The narrow range of radiocarbon dates are cited with a less stringent confidence interval (68%) than the standard requirement of 95%, which would have produced a much wider range.[14] The texts describing the relevant astronomical phenomena are extremely obscure.[15][16] For example, the inscription on the Li gui, a key text used in dating the conquest, can be interpreted in several different ways, with one alternative reading leading to the date of 9 January 1044 BC.[6]

Notes

- 1046 BC is the year endorsed by the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project, though doubts persist on this dating. See § Dating.

References

Citations

- Cambridge History of Ancient China, p. 233.

- Wu, note 40, 319 and note 41, 320

- Yin (2002), p. 1.

- Lee (2002), p. 32.

- Pankenier (1981–1982), p. 3.

- Lee (2002), p. 34.

- Lee (2002), pp. 33–34.

- Liu (2002), p. 4.

- Zhang (2002), p. 350.

- Lee (2002), pp. 31–34.

- Yin (2002), pp. 2–3.

- Pankenier (1981–1982), pp. 3–7.

- Lee (2002), p. 36.

- Keenan (2007), p. 147.

- Keenan (2002), pp. 62–64.

- Stephenson (2008), pp. 231–242.

Bibliography

- Keenan, Douglas J. (2002), "Astro-historiographic chronologies of early China are unfounded" (PDF), East Asian History, 23: 61–68.

- Keenan, Douglas J. (2007), "Defence of planetary conjunctions for early Chinese chronology is unmerited" (PDF), Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 10: 142–147.

- Lee, Yun Kuen (2002), "Building the chronology of early Chinese history", Asian Perspectives, 41 (1): 15–42, doi:10.1353/asi.2002.0006, hdl:10125/17161.

- Liu, Ci-Yuan (2002), "Astronomy in the Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project", Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 5 (1): 1–8, Bibcode:2002JAHH....5....1L.

- Pankenier, David W. (1981–1982), "Astronomical Dates in Shang and Western Zhou" (PDF), Early China, 7: 2–37.

- Stephenson, F. Richard (2008), "How reliable are archaic records of large solar eclipses?", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 39: 229–250, Bibcode:2008JHA....39..229S, doi:10.1177/002182860803900205.

- Wu, K. C. (1982). The Chinese Heritage. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-517-54475-X.

- Yin, Weizhang (2002), trans. Victor Cunrui Xiong, "New development in the research on the chronology of the Three Dynasties" (PDF), Chinese Archaeology, 2: 1–5.

- Zhang, Peiyu (2002), "Determining Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology through Astronomical Records in Historical Texts", Journal of East Asian Archaeology, 4: 335–357, doi:10.1163/156852302322454602.

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Chinese Stories/The Battle of Muye |