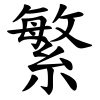

Traditional Chinese characters

Traditional Chinese characters (traditional Chinese: 正體字/繁體字; simplified Chinese: 正体字/繁体字, Pinyin: Zhèngtǐzì/Fántǐzì)[1] are Chinese characters, of any character set, that were created before 1946, later creations being designated simplified Chinese characters.

| Traditional Chinese | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Type | |

| Languages | Chinese |

Time period | Since 5th century AD |

Parent systems | Oracle Bone Script

|

Child systems | |

| Direction | Varies |

| ISO 15924 | Hant, 502 |

Traditional Chinese characters are used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau, as well as in most overseas Chinese communities outside Southeast Asia. In contrast, simplified Chinese characters are used in Mainland China, Malaysia, and Singapore in official publications.

The debate on traditional and simplified Chinese characters has been a long-running issue among Chinese communities. Currently, many overseas Chinese online newspapers allow users to switch between both character sets.

History

The modern shapes of traditional Chinese characters first appeared with the emergence of the clerical script during the Han dynasty and have been more or less stable since the 5th century (during the Southern and Northern Dynasties).

The retronym "Traditional Chinese" is used to contrast traditional characters with "simplified Chinese characters", a standardized character set introduced in the 1950s by the government of the People's Republic of China on Mainland China.

Modern usage in Chinese-speaking areas

Mainland China

Although simplified characters are endorsed by the government of China and taught in schools, there is no prohibition against using traditional characters. Traditional characters are used informally, primarily in handwriting, but also for inscriptions and religious text. They are often retained in logos or graphics to evoke yesteryear. Nonetheless, the vast majority of media and communications in China use simplified characters.

Hong Kong and Macau

In Hong Kong and Macau, Traditional Chinese has been the legal written form since colonial times. In recent years, however, simplified Chinese characters are used to accommodate Mainland Chinese tourists and immigrants.[2] The use of simplified characters has led to residents being concerned about protecting their local heritage.[3][4]

Taiwan

Taiwan has never adopted simplified characters. The use of simplified characters in official documents and educational settings is prohibited by the government of Taiwan, although simplified characters are mostly understood by any educated Taiwanese, as it takes little effort learn them, some stroke simplifications having already been in common use in handwriting.[5][6]

Philippines

.jpg.webp)

The Chinese Filipino community continues to be one of the most conservative in Southeast Asia regarding simplification. Although major public universities teach simplified characters, many well-established Chinese schools still use traditional characters. Publications such as the Chinese Commercial News, World News, and United Daily News all use traditional characters. So do some magazines from Hong Kong, such as the Yazhou Zhoukan. On the other hand, the Philippine Chinese Daily uses simplified characters.

DVD subtitles for film or television mostly use traditional Characters, that subtitling being influenced by Taiwanese usage and by both countries being within the same DVD region, 3.

United States

Having immigrated to the United States during the second half of the 19th century, well before the institution of simplified characters, Chinese-Americans have long used traditional characters. Therefore, US public notices and signage in Chinese are generally in traditional Chinese.[1]

Nomenclature

Traditional Chinese characters are known by different names within the Chinese-speaking world. The government of Taiwan officially calls traditional Chinese characters standard characters or orthodox characters (traditional Chinese: 正體字; simplified Chinese: 正体字; pinyin: zhèngtǐzì; Zhuyin Fuhao: ㄓㄥˋ ㄊㄧˇ ㄗˋ).[7] However, the same term is used outside Taiwan to distinguish standard, simplified, and traditional characters from variant and idiomatic characters.[8]

In contrast, users of traditional characters outside Taiwan—such as those in Hong Kong, Macau, and overseas Chinese communities, and also users of simplified Chinese characters—call the traditional characters complex characters (traditional Chinese: 繁體字; simplified Chinese: 繁体字; pinyin: fántǐzì; Zhuyin Fuhao: ㄈㄢˊ ㄊㄧˇ ㄗˋ), old characters (Chinese: 老字; pinyin: lǎozì; Zhuyin Fuhao: ㄌㄠˇ ㄗˋ), or full Chinese characters (traditional Chinese: 全體字; simplified Chinese: 全体字; pinyin: quántǐ zì; Zhuyin Fuhao: ㄑㄩㄢˊ ㄊㄧˇ ㄗˋ) to distinguish them from simplified Chinese characters.

Some users of traditional characters argue that traditional characters are the original form of the Chinese characters and cannot be called "complex". Similarly, they argue that simplified characters cannot be called "standard" because they are not used in all Chinese-speaking regions. Conversely, supporters of simplified Chinese characters object to the description of traditional characters as "standard", since they view the new simplified characters as the contemporary standard used by the vast majority of Chinese speakers. They also point out that traditional characters are not truly traditional, as many Chinese characters have been made more elaborate over time.[9]

Some people refer to traditional characters as simply proper characters (Chinese: 正字; pinyin: zhèngzì or Chinese: 正寫; pinyin: zhèngxiě ) and to simplified characters as "simplified-stroke characters" (traditional Chinese: 簡筆字; simplified Chinese: 简笔字; pinyin: jiǎnbǐzì) or "reduced-stroke characters" (traditional Chinese: 減筆字; simplified Chinese: 减笔字; pinyin: jiǎnbǐzì) (simplified- and reduced- are actually homophones in Mandarin Chinese, both pronounced jiǎn).

Printed text

When printing text, people in mainland China and Singapore use the simplified system. In writing, most people use informal, sometimes personal simplifications. In most cases, an alternative character (異體字) will be used in place of one with more strokes, such as 体 for 體. In the old days, there were two main uses for alternative characters. First, alternative characters were used to name an important person in less formal contexts, reserving traditional characters for use in formal contexts, as a sign of respect, an instance of what is called "offence-avoidance" (避諱) in Chinese. Secondly, alternative characters were used when the same characters were repeated in context to show that the repetition was intentional rather than a mistake (筆誤).

Computer encoding and fonts

In the past, Traditional Chinese was most often rendered using the Big5 character encoding scheme, a scheme that favours Traditional Chinese. However, Unicode, which gives equal weight to both simplified and traditional Chinese characters, has become increasingly popular as a rendering method. There are various IMEs (Input Method Editors) available to input Chinese characters. There are still many Unicode characters that cannot be written using most IMEs, one example being the character used in the Shanghainese dialect instead of 嗎, which is U+20C8E 𠲎 (伐 with a 口 radical).

In font filenames and descriptions, the acronym TC is used to signify the use of traditional Chinese characters to differentiate fonts that use SC for Simplified Chinese characters.[10]

Web pages

The World Wide Web Consortium recommends the use of the language tag zh-Hant as a language attribute and Content-Language value to specify web-page content in Traditional Chinese.[11]

Usage in other languages

In Japanese, kyūjitai is the now-obsolete, non-simplified form of simplified (shinjitai) Jōyō kanji. These non-simplified characters are mostly congruent with the traditional characters in Chinese, save for a few minor regional graphical differences. Furthermore, characters that are not included in the Jōyō list are generally recommended to be printed in their original non-simplified forms, save for a few exceptions.

In Korean, traditional Chinese characters are identical with Hanja (now almost completely replaced by Hangul for general use in most cases, but nonetheless unchanged from Chinese except for some Korean-made Hanja).

Traditional Chinese characters are also used by non-Chinese ethnic groups, especially the Maniq people—of southern Yala Province of Thailand and northeastern Kedah state of Malaysia—for writing the Kensiu language.[12][13]

See also

- Simplified Chinese characters

- Debate on traditional and simplified Chinese characters

- Chữ Nôm

- Hanja

- Kaishu

- Kanji

- Kyūjitai (旧字体 or 舊字體 – Japanese traditional characters)

- Multiple association of converting Simplified Chinese to Traditional Chinese

References

- See, for instance, https://www.irs.gov/irm/part22/irm_22-031-001.html (Internal Revenue Manual 22.31.1.6.3 – "The standard language for translation is Traditional Chinese."

- Li, Hanwen (李翰文). 分析:中國與香港之間的「繁簡矛盾」. BBC News (in Chinese). Retrieved 2018-07-01.

- Lai, Ying-kit (17 July 2013). "Hong Kong actor's criticism of simplified Chinese character use stirs up passions online | South China Morning Post". Post Magazine. scmp.com. Retrieved 2018-07-01.

- "Hong Kong TV station criticized for using simplified Chinese". SINA English. 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2018-07-01.

- Cheung, Yat-Shing (1992). "Language variation, culture, and society". In Bolton, Kingsley (ed.). Sociolinguistics Today: International Perspectives. Routledge. pp. 211.

- Price, Fiona Swee-Lin (2007). Success with Asian Names: A Practical Guide for Business and Everyday Life. Nicholas Brealey Pub. ISBN 9781857883787 – via Google Books.

- 查詢結果. Laws and Regulations Database of The Republic of China. Ministry of Justice (Republic of China). 2014-09-26. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- Academy of Social Sciences, (1978), Modern Chinese Dictionary, The Commercial Press: Beijing.

- Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 81.

- "Noto CJK". Google Noto Fonts.

- "Internationalization Best Practices: Specifying Language in XHTML & HTML Content". W3.org. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- Phaiboon, D. (2005). Glossary of Aslian languages: The northern Aslian languages of South Thailand. Mon–Khmer Studies, 36: 207-224. Retrieved from http://sealang.net/sala/archives/pdf8/phaiboon2006glossary.pdf

- Bishop, N. (1996). Who's who in Kensiw? Terms of reference and address in Kensiw. The Mon–Khmer Studies Journal, 26, 245-253. Retrieved from "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2010-12-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)