Beau Brummel (1924 film)

Beau Brummel is a 1924 American silent film historical drama starring John Barrymore and Mary Astor. The film was directed by Harry Beaumont and based upon Clyde Fitch's 1890 play, which had been performed by Richard Mansfield,[2] and depicts the life of the British Regency dandy Beau Brummell.

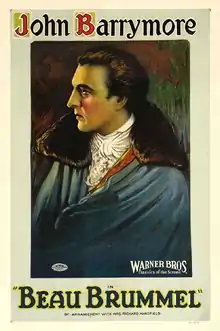

| Beau Brummel | |

|---|---|

theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Harry Beaumont |

| Written by | Dorothy Farnum |

| Based on | Beau Brummel (1890 play) by Clyde Fitch |

| Starring | John Barrymore Mary Astor Carmel Myers Willard Louis Irene Rich |

| Music by | James Schafer |

| Cinematography | David Abel |

| Edited by | Howard Bretherton |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 135 minutes (10 reels) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent (English intertitles) |

| Budget | $343,000[1] |

| Box office | $495,000[1] |

Several years after Barrymore's death, his daughter Diana Barrymore was shown a special screening of this film as she had never seen her father in any of his silent films.[3]

In 1952, the film entered the public domain in the United States because Warner Bros. did not renew its copyright registration in the 28th year after publication.[4]

Plot

In 1795, the cream of English aristocracy attend the wedding of "tradesman's daughter" Margery. She loves Beau Brummel, a penniless captain in the Tenth Hussars, but has been pressured into agreeing to marry Lord Alvanley, exchanging her family's wealth for social standing and a title. When Brummel comes to see her just before the wedding, she begs him to take her away, but her ambitious mother, Mrs. Wertham, intervenes, and Margery gives way. Embittered, Brummel decides to seek revenge against society using his "charm, wit and personal appearance".

At a dinner given by the Prince of Wales for the officers of his regiment, the Prince is attracted to Mrs. Snodgrass, the innkeeper's wife. When Brummel rescues him from the irate husband, he takes a great liking to the captain, enabling Brummel to attach himself to His Royal Highness.

By 1811, Brummel has made his house in London the "rendezvous of the smart world" and himself the arbiter of fashion. When Lord Henry Stanhope catches him dallying with his infatuated wife, a duel ensues. Lord Henry misses, whereupon Brummel fires his pistol into the air. Afterward, however, Brummel informs Lady Hester Stanhope that he never loved her. She attracts the attention of the womanizing Prince.

She and another enemy he has made set out to turn the Prince against him. Brummel unwittingly helps them, having become too sure of his position; he is rude to his royal friend. Brummel turns his attentions to the Duchess of York, the Prince's sister-in-law. She agrees to a late night private supper, but Lady Margery shows up first. She warns him that his enemies are hard at work; one knows about the rendezvous. The Prince arrives unannounced, expecting to find the Duchess, but is (pleasantly) surprised to find Lady Margery instead. When she rejects his initial advances, he offers to appoint Brummel the Ambassador to France. Lady Margery is delighted at the prospect, but it is all for naught. Shortly afterward, the two men quarrel openly, and neither is interested in a reconciliation.

No longer able to fend off his creditors as a result of the withdrawal of the Prince's favor, Brummel flees to Calais to avoid going to debtors prison, accompanied only by his loyal butler Mortimer. Years pass, and the Prince, now King George IV, stops at Calais. In his entourage is Lady Margery. Both see Brummel standing by the side of the road. Without his master's knowledge, Mortimer goes to see the King, pretending to represent Brummel in an effort to heal the breach. When Brummel finds out, he discharges Mortimer. Lady Margery comes to see Brummel in his garret. Her husband has died, and she asks him to marry her. He turns her down, saying he is too worn out and tired, perhaps even of love. After she departs, his resolution wavers, but he regains control of himself.

In old age, Brummel ends up in the hospital prison of Bon Saveur. The ever-faithful Mortimer visits him, but Brummel's mind has deteriorated - he does not recognise his old servant at first. Mortimer informs him that the King has died and that Lady Margery is very ill. The scene shifts to the latter's bed. Her spirit leaves her body and travels to Brummel's cell. When Brummel also dies, their youthful souls are joyfully reunited.

Cast

- John Barrymore as George Bryan "Beau" Brummel

- Mary Astor as Lady Margery Alvanley

- Willard Louis as Prince of Wales

- Carmel Myers as Lady Hester Stanhope

- Irene Rich as Frederica Charlotte, Duchess of York, sister-in-law of the Prince of Wales

- Alec B. Francis as Mortimer, Brummel's butler

- William Humphrey as Lord Alvanley

- Richard Tucker as Lord Henry Stanhope

- George Beranger as Lord Byron

- Clarissa Selwynne as Mrs. Wertham

- John J. Richardson as Poodles Byng

- Claire de Lorez as Lady Manly

- Michael Dark as Lord Manly

- Templar Saxe as Desmond Wertham

- James A. Marcus as Snodgrass, the innkeeper

- Betty Brice as Mrs. Snodgrass

- Roland Rushton as Mr. Abrahams, a creditor of Brummel's

- Carol Holloway as Kathleen, the maid

- Kate Lester as Lady Miora

- Rose Dione as Madame Bergere

- C. H. Chaldecotte as Timothy

- F. F. Guenste as Parkyns, valet to the Prince of Wales

- Beaudine Anderson as child (uncredited)

See also

Production

Shooting on the film began in September 1923.

Barrymore and Astor were conducting an affair during filming.[5]

Barrymore and Willard Louis, who played the Prince of Wales, frequently told bawdy jokes rather than say their lines, since it was a silent film. However, they did not take into account deaf audience members who could lip read what they were saying. Many of these patrons wrote to complain about the actors' antics.[5]

The picture was a remake of a 1913 version and was in turn remade in 1954 with Stewart Granger, Elizabeth Taylor and Peter Ustinov, although the latter film restored the original spelling of "Brummell."

Reception

Box Office

According to Warner Bros records the film earned $453,000 domestically and $42,000 foreign.[6]

Preservation status

Beau Brummel survives today in various edits, the original 135 minute release and 80 minute and 71 minute versions. The short versions usually cut Carmel Myers' scenes.

References

- Glancy, H Mark (1995). "Warner Bros Film Grosses, 1921–51: the William Schaefer ledger". Historical Journal of Film Radio and Television. 15: 55–73. doi:10.1080/01439689500260031.

- Beau Brummel at silentera.com

- The Barrymores in Hollywood by James Kotsilibas Davis, c.1981

- Pierce, David (June 2007). "Forgotten Faces: Why Some of Our Cinema Heritage Is Part of the Public Domain". Film History: An International Journal. 19 (2): 125–43. doi:10.2979/FIL.2007.19.2.125. ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 25165419. OCLC 15122313. S2CID 191633078.. See Note #44, pg. 142.

- Felicia Feaster. "Beau Brummel (1924)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- Warner Bros financial information in The William Shaefer Ledger. See Appendix 1, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, (1995) 15:sup1, 1-31 p 2 DOI: 10.1080/01439689508604551

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beau Brummel. |