Beaumont High School (St. Louis)

Beaumont High School was a public high school in St. Louis, Missouri, United States. It was part of the St. Louis Public Schools, and closed after the final graduating class on May 14, 2014.[1] After Beaumont was founded in 1926, it became noted for producing several Major League Baseball players in the 1940s and 1950s. During the Civil Rights Movement, the high school's integration was featured in a documentary film that was nominated for an Academy Award. After the closure of Little Rock Central High School after its integration crisis, three members of the Little Rock Nine completed coursework at Beaumont. After the 1970s, however, the school re-segregated as an all-black school, and from the 1970s through the 1990s, the school suffered deteriorating physical conditions, security, and academics.

| Beaumont High School | |

|---|---|

Signage and front of Beaumont High School, July 2010 | |

| Location | |

| |

United States | |

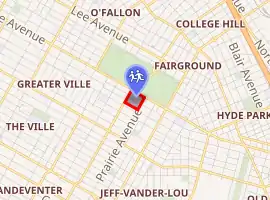

| Coordinates | 38.6626°N 90.2219°W |

| Information | |

| Type | Comprehensive Public High School |

| Opened | 1926 |

| Closed | 2014[1][2] |

| School district | St. Louis Public Schools |

| Superintendent | Kelvin Adams |

| Principal | Michael Brown |

| Faculty | 39.55 (on full-time equivalent (FTE) basis)[3] |

| Grades | 10–12 |

| Enrollment | 577 (2017-18)[3] |

| Student to teacher ratio | 14.59[3] |

| Campus type | Urban |

| Color(s) | Blue and gold |

| Mascot | Bluejacket |

| Newspaper | Beaumont Speaks |

| Yearbook | Caduceus |

| Website | School website |

After a renovation in the early 1990s, the school's physical condition improved, but gang violence at the school led to several incidents, including a classroom invasion by a group of armed youth in 1994. The school continued to struggle with a high dropout rate and low standardized test scores. As of 2010, the school offered its nearly 800 students a variety of athletics and activities, including football, basketball, cross country and track, Future Business Leaders of America, Health Occupation Students of America, and job shadowing programs. It also had several notable alumni, including more than a dozen Major League Baseball or NFL players, and a variety of political and education leaders. For the 2011–2012 school year, Beaumont was converted into a 10th through 12th grade technical high school and no longer accepted 9th grade students.

History

Construction and early years

Due to the limited space at Yeatman High School, the city's only high school for whites on the north side, the St. Louis Public Schools ordered the construction of Beaumont High School in 1925.[4] The cost of land acquisition for the school was $200,000, which purchased Robison Field, the home of the St. Louis Cardinals from 1893 to 1920.[5][6] Designed by R.M. Milligan, the school was built at a cost of more than $1.5 million and opened in January 1926 with a capacity of 3,500 students.[4] The school was named for the early St. Louis surgeon, William Beaumont, after a petition from the St. Louis Medical Society in December 1922.[7] Prior to its renovation in the 1990s, the original building had five levels including the basement and attic level, 96 classrooms, a rifle range in the attic, three tennis courts, and a three-story 2,250-seat auditorium.[8] Its yearbook, the Caduceus, and its original newspaper, The Digest, were tributes to the medical background of the school's namesake.[8]

By 1933, the school had more than 2,800 students, and by 1937, it had increased to 3,100 students.[9][10] Beaumont produced several notable Major League Baseball players from the late 1930s through the early 1950s. In 1944 alone, the school's baseball team had five players who went on to the Major Leagues: Earl Weaver, Roy Sievers, Jim Goodwin, Bob Wiesler and Bobby Hofman.[11]

Integration and re-segregation

After the Brown v. Board of Education decision in May 1954, the St. Louis Public Schools began to implement their desegregation plan; Beaumont High School, formerly an all-white school, was among the first to desegregate.[12] After Beaumont was racially integrated in September 1954, a knife fight broke out in the school between African American and white students that led to coverage in Jet magazine.[13] Following the incidents, a short documentary film titled A City Decides reenacted the events of integration at the school and portrayed the reaction of teachers to student racial conflict.[14] The film was directed by Charles Guggenheim and aired on NBC affiliates, and in 1956 it was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Short Subject.[14] However, not all white-black interactions in the 1950s were negative; several black alumni reported initially positive experiences during the integration process.[12] In 1957, three members of the Little Rock Nine transferred to Beaumont to complete some of their high school coursework.[15]

Despite de jure integration by 1955, Beaumont experienced re-segregation during the 1970s to become an all-black high school.[16] It was during this time that Beaumont experienced several racial conflicts; on February 13, 1970, a celebration of Negro History Week (now known as Black History Month) ended early due to racially inflammatory skits.[17] The skits included profanity and depicted an attack on a white teacher who had made racially derogatory remarks, and students were urged to resort to violence.[17] The principal, John A. Nelson, was transferred from the school, and three teachers were fired.[17] The early end to the week's celebration led to an incident in which 20 students damaged school property and assaulted two police officers.[17] Even after a court mandated desegregation transfer program, Beaumont remained a de facto segregated all-black school from the 1980s through the 2000s.[18]

Physical deterioration and renovation

During the 1970s and 1980s, the school saw significant physical deterioration. By the late 1980s, the school's football playing field had deteriorated, and it was often "littered with broken bottles and other hazardous debris".[19] Interior athletic facilities also deteriorated to the extent that the school's junior varsity basketball team was forced to practice on the school auditorium stage.[19] To address some of these issues, the St. Louis Board of Education passed an $7.3 million bond issue in 1990 for renovations at Beaumont.[20] Due to the renovations, Beaumont students were relocated to McKinley High School from 1991 to 1993.[21][22] The renovations significantly improved conditions at the school, with new lockers, flooring, ceilings, and furniture, while both the swimming pool and auditorium were restored.[23] The school's two gymnasiums were combined into one larger facility.[23]

Security issues

Despite attempts to improve conditions, crime and gang problems plagued Beaumont in the 1990s: in response to threats of gang violence in March 1991, the St. Louis Police Department surrounded the school with dozens of officers.[24] According to self-reporting from gang members and the police, Beaumont was in Crips territory, although some students affiliated with the Bloods gang also attended.[24] One student estimated in 1991 that as many as 20 percent of students were affiliated with a gang.[24] Although claiming that the gang membership estimate was too high, an administrator admitted that Beaumont did "have some violent students" and "I've known students who have been shot, killed and stabbed."[24] During the 1991 Annie Malone Parade that was to end at Beaumont, gang violence slowed part of the parade near its completion.[25]

In what has been described as the "low point" of Beaumont's history, on February 16, 1994, a gang fight broke out in the cafeteria; following the incident, a group of a dozen armed youth entered a building classroom and threatened to kill one student who had escaped the fight. After a scuffle, the student escaped via a window, and the group fled the building.[26][27] Following the incident, security was temporarily increased at Beaumont, and St. Louis Mayor Freeman Bosley, Jr. spoke to the student body.[28] With the start of the 1994–1995 school year, Beaumont and the other St. Louis public high schools received metal detectors to reduce the presence of guns on campus.[29] Beaumont administrators also introduced the U.S. Army Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps program.[30] The JROTC program was designed to both reduce the dropout rate at Beaumont and combat the problem of gang activity at the school.[30] In addition to improved security measures, district officials hired Floyd Crues, a former alternative high school principal, to head Beaumont; his changes to school practices were credited with improving the climate at Beaumont.[31] Under Crues, Beaumont's discipline problems decreased, and he received comparisons to New Jersey high school principal Joe Clark, the inspiration for the 1989 film Lean on Me.[31]

Despite increased security measures, violence continued at and near the school: in October 1994, a Beaumont student was shot in the street outside the school as the building was being dismissed.[32] Also, during the JROTC program's first semester in the spring of 1995, one of its students was murdered by another Beaumont student in a case of mistaken identity.[33] During the next year, in October 1995, a Beaumont student shot at a school bus that was taking other students to Lindbergh High School after gang signs were exchanged.[34] In March 1996, in another bus incident, a student shot and critically injured a Beaumont bus driver, and shot and killed a pregnant Beaumont student.[35]

Academic issues

Starting in the 1970s, academic problems began to surface at Beaumont High School; one student who graduated in 1974 found after testing that she was able to read at only a third grade level.[36] The school also suffered from financial and academic problems in the 1980s and 1990s, with teachers paying for basic supplies and textbooks during the early 1990s.[37] According to an internal report from the St. Louis Public Schools, only 26.1 percent of Beaumont students who entered in September 1984 graduated in June 1988.[38] 40.8 percent officially dropped out, while an additional 19.4 percent "did not return" but also did not request transcripts as a transfer student.[38] In an effort to reduce the dropout rate in 1991, administrators developed "Project Courage", a life skills and self-esteem course. However, its curriculum and standards were weak, and the district was accused of pervasive inequality amid disparities between comprehensive high schools such as Beaumont and newly implemented magnet schools.[39] Project Courage, for its part, had little effect on educational performance.[40]

In 1994, Beaumont in particular was noted for its lack of curricular strength in mathematics and language; advanced English courses were eliminated at the school in 1995 by the board of education, and although a computer-based remedial mathematics program was mandated by court order in 1989, it still had not been implemented by 1994.[18] In response to the allegations of lack of academic rigor at Beaumont, St. Louis Public Schools Superintendent David J. Mahan argued that Beaumont would continue to offer advanced social studies, science and foreign language courses, and that the remedial mathematics program had not been implemented due to the 1991–1993 renovation project.[41] Mahan also argued that "The schools indeed are improving. They are not failing."[41] However, advanced mathematics courses such as calculus were not offered at Beaumont due to lack of student readiness, the drama club was cancelled, and the computer-aided reading program had no computers.[40] By the 1995–1996 school year, some of the problems had been rectified: the mathematics curriculum was upgraded and computer courses were implemented.[42] However, Beaumont lacked both an orchestra and a drama program, and only after inquiries from local media was a band director hired to replace one who had quit three months earlier.[42] Dropout rates remained particularly high through the 1990s; education expert and Harvard professor Gary Orfield noted, "I've never seen a graduation rate as low as I've seen in the central city of St. Louis."[43]

Improvements

By the late 1990s, security problems at the school had decreased, and both students and faculty noted that the school atmosphere was "calmer".[44] The efforts of Floyd Crues to improve discipline succeeded via a student safety task force, in which students were encouraged to report potential acts of violence.[44] By 1998, Beaumont was regarded as a "turnaround" due to the efforts of Crues, who further instituted zero tolerance policies on gang activity at the school.[45]

Progress also was made during the late 1990s in academic performance. In 1996–1997 school year, more students gained induction into the National Honor Society than had in the previous five years; 10 students met the requirements of a 3.3 grade point average for three consecutive semesters.[46] Some part of the academic progress was credited to the principal, Floyd Crues, who created a school-within-a-school at Beaumont to teach students about banking and finance.[45] The school's finance academy was lauded as one of only two such academies in the state.[47] In January 1999, Monica Washington, a Beaumont senior, presented research at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[48] The next year, the Open Society Institute began funding the Urban Debate League, an association of St. Louis high school debate programs; Beaumont thus began its speech and debate program.[49]

In the early 2000s, the finance and jobs program at Beaumont began to show results; students at the school began job shadowing programs throughout the region, while students at the Beaumont Academy of Finance finished third in a national stock-picking contest sponsored by CNBC.[50][51] After the departure of Floyd Crues, new principal Travis L. Brown continued to attempt to improve academics; in 2001, Brown began to focus efforts on scores on the state achievement tests.[52] It was also in 2001 that Beaumont sprinter Orlando Payton ran a 100 meter dash in 10.2 seconds, which was the best time in the United States for the year.[53] Although academic achievement remained among the worst in the region, graduation rates improved to roughly 50 percent by 2003, nearly double their rate in the mid-1990s.[54]

Security gains remained tenuous, however, as in September 2003, after a significant fight at the school, a student being treated for injuries was discovered with a loaded gun.[55] On the last day of classes of the 2004–2005 school year, police were forced to disperse a brawl of more than 200 students and others outside the school.[56] In October 2008, a fire broke out in a classroom, causing the evacuation of the building; in November 2008, another fire was lit in a bathroom.[57] Investigators ruled both fires as arson.[57] Academic gains also were hampered by the loss of the St. Louis Public School's accreditation during the 2006–2007 school year. After the loss, Beaumont had difficulty replacing a French instructor by the beginning of the 2007–2008 year.[58][59] Also, the issue of de facto segregation remained; Beaumont's neighborhood boundaries caused its student population to remain solidly all-black through the 2000s.[60]

Later steps taken to curb discipline incidents at the school included the formation of the Young Gentlemen's Club in 2007, in which male students wore ties and attempted to improve their etiquette.[61] In 2007, the school and its principal, Travis Brown, were featured in The New York Times.[62] The article described the building as "loom[ing] over the troubled neighborhood like a castle of trapdoors and passageways", although it also emphasized the positive role of Brown and other administrators in encouraging academics and discipline at the school.[62] During the 2009–2010 school year, Beaumont also became one of the first high schools in the country to offer a respiratory therapy program to teach students hands-on skills.[63]

Last years

As of the 2010–2011 school year, Beaumont operated on an 8:05 am to 3:02 pm schedule.[64] Its principal, Michael Brown, assumed the position in August 2009 after serving as an assistant principal at Clyde C. Miller Career Academy.[65] Starting in 2011–2012, Beaumont was converted into a technical high school with "employment ready" programs.[66] To that end, the school no longer accepted 9th grade students, and 10th through 12th grade students attended a comprehensive high school for half of the school day, then transferred to Beaumont for technical education for the other half of the day.[66][67] In preparation for the conversion, the school underwent $500,000 in physical upgrades.[66]

The school song was as follows:[68]

Beaumont High, we pledge our love

Let our chorus ring above

Beaumont's warm and friendly walls

Campus broad and ample halls

Pay we now the honor due

To Beaumont's Gold and Blue

The Gold of Youth

The Blue of Truth

and staunch Loyalty.

Seventy seniors graduated on May 14, 2014, as the final class of the 88-year-old institution.[1]

Activities

For the 2010–2011 school year, the school offered ten activities approved by the Missouri State High School Activities Association (MSHSAA): boys' and girls' basketball, boys' and girls' cross country, boys' and girls' track and field, girls' volleyball, 11-man football, sideline cheerleading, and baseball.[69] In addition to its current activities, Beaumont students have won several state championships, including:

- Baseball: 1956, 1960

- Boys' Basketball: 1933, 1942, 1943, 1947, 1948, 1956

- Boys' Cross Country: 1953, 1957, 1959

- Boys' Swimming and Diving: 1946, 1949, 1950

- Boys' Outdoor Track and Field: 1942, 1944, 1945, 1946, 1960, 1961, 1967

- Boys' Indoor Track and Field: 1959, 1960, 1966

The school has produced three singles and three doubles tennis state champions, and two individual wrestling state champions.[70]

Demographics

In the 2009–2010 school year, Beaumont had an enrollment of 782 students with 48.7 full-time-equivalent teachers, for a student-teacher ratio of 16.1.[71] Nearly 80 percent of students qualified for free or reduced price lunches.[72] After 2005, more than 99 percent of the student population at Beaumont was African American; in addition to its African American population, during the 2009–2010 school year, two White students and one Hispanic student attended the school.[72]

| Year | Black | White | Hispanic | Asian |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 99.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| 2007 | 99.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2008 | 99.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| 2009 | 99.3 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| 2010 | 99.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Year | Percent |

|---|---|

| 2006 | 77.3 |

| 2007 | 71.1 |

| 2008 | 59.5 |

| 2009 | 56.9 |

| 2010 | 79.9 |

| Year | Average years experience | Percent with master's degree |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 9.6 | 28.9 |

| 2007 | 11.4 | 35.3 |

| 2008 | 10.1 | 37.6 |

| 2009 | 9.5 | 36.9 |

| 2010 | 7.4 | 46.5 |

| Year | Regular certification | Temporary certification | Substitute or no certification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 69.7 | 24.7 | 5.6 |

| 2006 | 58.9 | 22.2 | 18.9 |

| 2007 | 76.7 | 13.7 | 9.6 |

| 2008 | 75.9 | 13.7 | 9.6 |

| 2009 | 79.6 | 7.4 | 13.0 |

Academic and discipline issues

For many years Beaumont had a significant dropout rate; for the 2009–2010 school year, more than 42 percent of students dropped out compared to the Missouri state dropout rate at that time of 3.5 percent.[72] Beaumont also had a significant discipline incident rate of 13.9 percent, more than seven times the average Missouri rate.[72][73] Following the passage of No Child Left Behind in 2001, Beaumont met the requirements for adequate yearly progress (AYP) only once. In 2009, Beaumont students achieved 51.9 percent proficiency in communication arts, allowing the school to meet the annual proficiency target of 59.2 within a confidence interval.[72] In addition, Beaumont graduates averaged lower first and second semester grades during their first year in college than the average Missouri graduate, and as of 2010, more than 80 percent of Beaumont graduates enrolling in a public university in Missouri required remedial coursework in either English or mathematics.[74][75]

| Year | Graduates | Cohort dropouts‡ | Graduation rate† |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 165 | 272 | 37.8 |

| 2007 | 158 | 266 | 37.3 |

| 2008 | 234 | 315 | 42.6 |

| 2009 | 208 | 455 | 31.4 |

| 2010 | 189 | 242 | 43.9 |

| ‡ Cohort dropouts is the number of students from the grade level graduating for that year who dropped out. † Graduation rate is calculated as number of graduates divided by number of graduates plus dropouts, multiplied by 100. | |||

| Year | Total dropouts‡ | Dropout rate† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 378 | 29.0 | |

| 2007 | 295 | 24.5 | |

| 2008 | 306 | 31.5 | |

| 2009 | 305 | 37.6 | |

| 2010 | 293 | 42.5 | |

| ‡ Total dropouts is the number of students who dropped out of school for the school year. † Dropout rate is calculated as number of total dropouts/(September enrollment plus transfers in and minus transfers out + September enrollment)/2). | |||

| Year | Total incidents‡ | Incident rate† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 330 | 23.7 | |

| 2007 | 369 | 30.3 | |

| 2008 | 211 | 19.9 | |

| 2009 | 244 | 27.1 | |

| 2010 | 109 | 13.9 | |

| ‡ Total incidents is the number of incidents in which as a result a student was removed for ten or more consecutive days from a traditional classroom. † Incident rate is calculated as enrollment divided by total incidents. | |||

Notable people

Alumni

- Gene Barth: NFL official[76]

- Bud Blattner: Major League Baseball player and broadcaster[77]

- Roy Branch: Major League Baseball player (Seattle Mariners)

- Chuck Diering: Major League Baseball player[77]

- Jim Goodwin: Major League Baseball player[77]

- Bobby Hofman: Major League Baseball player[77]

- Ken Iman: NFL player and coach[78]

- Frank M. Karsten: U.S. Representative from Missouri[79]

- Jack Maguire: Major League Baseball player[77]

- Bobby Mattick: MLB player (Chicago Cubs, Cincinnati Reds) and Toronto Blue Jays manager

- Lloyd Merritt: Major League Baseball player[77]

- Bob Miller: Major League Baseball player[77]

- Joe Moore: first-round pick in 1971 NFL Draft[80]

- Tommie Pierson: state representative[81]

- Pete Reiser: MLB player (Brooklyn Dodgers, Boston Braves, Pittsburgh Pirates, Cleveland Indians)

- Bud Schwenk: NFL player[82]

- Roy Sievers: Major League Baseball player[77][83]

- Cory Spinks: boxer[1]

- Lee Thomas: Major League Baseball player[77]

- Quincy Troupe: poet and journalist[84]

- Earl Weaver: Major League Baseball player and manager[77]

- Ronnie L. White: Missouri Supreme Court justice; first African American chief justice[85]

- Mary Wickes: film and television actress[86]

- Bob Wiesler: Major League Baseball player[77]

- Dick Williams: Major League Baseball player and manager[87]

Others

- Elizabeth Eckford: member of Little Rock Nine; attended one course to complete high school requirements[15]

- Will Franklin: fourth-round pick in 2008 NFL Draft; attended Beaumont for two years

- Carlotta Walls LaNier: member of the Little Rock Nine; attended one course to complete high school requirements[15]

- Thelma Mothershed: member of Little Rock Nine; attended one course to complete high school requirements[15]

- Pete Reiser: Major League Baseball player; attended Beaumont for two years (David Porter's Biographical dictionary of American sports: 1992–1995)

- Tom Stanton: Major League Baseball player; coached and taught at Beaumont[88]

References

- "Beaumont High School graduates its final class". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. May 15, 2014.

- "Impending closure of Beaumont High tells a larger story". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. August 17, 2013.

- "BEAUMONT CTE HIGH SCHOOL". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- Fairgrounds Neighborhood: Schools.

- Fox, Tim (1995). Where We Live: a Guide to St. Louis Communities. St. Louis, Missouri: Missouri Historical Society Press. pp. 150. ISBN 978-1-883982-12-6., 150.

- Bosenbecker, Ray (2004). So, Where'd You Go to High School?. 1. St. Louis, Missouri: Virginia Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-891442-30-8.

- "Petition to Name School After Dr. Wm. Beaumont". Journal of the Missouri State Medical Association. St. Louis, Missouri: Missouri State Medical Association. 19 (12): 518–519. December 1922. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- Dillon, Dan (2005). So, Where'd You Go to High School: The Baby Boomer Years. 2. St. Louis, Missouri: Virginia Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 1-891442-33-3.

- Edwards, Ward; Luella St. Clair Moss; Charles C. Schuttler (1933). Annual Report of the Missouri Library Commission. 27. Jefferson City, Missouri., 28.

- Edwards, Ward; Luella St. Clair Moss; Charles C. Schuttler (1937). Annual Report of the Missouri Library Commission. 31. Jefferson City, Missouri., 21.

- Brennan, Charlie; Bridget Garwitz; Joe Lattal (2006). Here's Where: a Guide to Illustrious St. Louis. St. Louis, Missouri: Missouri Historical Society Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-883982-57-7.

- Freeman, Gregory (January 18, 1998). "High School History Moves into Spotlight". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- "St. Louis Students Act to End Racial Flare-Ups". Jet. Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company. March 24, 1955. p. 24. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- McCarthy, Ann (2010). The Citizen Machine: Governing by Television in 1950s America. New York: The New Press. pp. 99–101. ISBN 978-1-59558-498-4..

- LaNier, Carlotta Walls; Lisa Frazier Page; Bill Clinton (July 2010). A Mighty Long Way: My Journey to Justice at Little Rock Central High School. ISBN 9780345511010., 205.

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. February 22, 1988 http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Retrieved July 30, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Tangle with Police". Youngstown Vindicator. Youngstown, Ohio. February 14, 1970. p. 8. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Freivogel, William H. (May 15, 1994). "40 Years After Ruling, City Schools Are Failing". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. February 27, 1988 http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Retrieved July 30, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. June 27, 1990 http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Retrieved July 30, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. September 4, 1991 http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Retrieved July 30, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Principals Are In Vanguard Against Chaotic Year". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. August 15, 1992. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Eardley, Linda (September 3, 1993). "'Beautiful' Beaumont High Facelife Finished". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. March 20, 1991 http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Retrieved July 30, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. May 21, 1991 http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Retrieved July 30, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Little, Joan (February 19, 1994). "Armed Youths Hunt Student in Classroom". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- "Pupils Told to 'Run for Your Lives'". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. February 22, 1994. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Little, Joan (March 3, 1994). "Bosley Vows to Ensure Safe Schools". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Little, Joan (June 15, 1994). "City Schools to Get Metal Detectors". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Henson Pope, Sharon (February 6, 1995). "Junior ROTC: High Goals, Hopes". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Autman, Samuel (September 29, 1996). "In for the Long Haul: Crues Control Steers Revamped Beaumont High". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Bryan, Bill (October 21, 1994). "Teen-ager Shot, Wounded Near Beaumont High". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Nower, Lia (May 19, 1995). "Family, Friends Mourn Youth – ROTC Student was Slain by Gunfire". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Memon Yaqub, Reshma (October 14, 1995). "Schools' Rough Week Spurs Action". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Bryan, Bill (March 1, 1996). "Student, 15, Slain on Bus – Gunman Kills Pregnant Teen, Wounds Driver at Bus Stop". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Little, Joan (March 17, 1996). "For Those Who Stay in City, Choices and Opportunities, but the St. Louis School System is Full of Potholes that Even the Brightest Must Work to Overcome". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. March 25, 1991 http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Retrieved July 30, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. May 24, 1992 http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Retrieved July 30, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Little, Joan (February 20, 1994). "Discrimination in City Schools Lives On, But Basis is Magnet Schools, Not Race". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Freivogel, William H. (June 13, 1994). "After 40 Years, Old Afflictions Dog Desegregation's Trail". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Mahan, David J. (May 22, 1994). "Letters from the People". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Freivogel, William H. (March 24, 1996). "History Lessons: Class and Court Ponder Progress in Schools for Blacks". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Little, Joan (July 1, 1996). "Hammonds v. Dropout Rate, as New Chief, Keeping Students in School Will Be a Challenge". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Carroll, Colleen (September 1, 1997). "City Schools Beefing Up Security". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Freeman, Gregory (April 23, 1998). "Beaumont High School's Turnaround is Largely Based on a Creative Principal". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Autman, Samuel (April 27, 1997). "'Nerd Patrol' - For Bright Beaumont Students, Study is its Own Reward". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Mueller, Michelle (December 7, 1998). "Finance Academy Gives Beaumont High Students Taste of Business World". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- "Two St. Louis Students Present Science Reports at Conference". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. January 24, 1999. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Mueller, Michelle (February 21, 2000). "Urban Debate Students are Gaining Essential Skills". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Pierce, Rick (February 2, 2001). "Students Hit 'Paydirt' on Virtual Wall Street; Beaumont High Teens Finish Third in U.S. Contest". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Cohn, Cathy (February 12, 2001). "Students Gain Firsthand Experience About 'Dream' Jobs in Shadow Program". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Hacker, Holly (May 3, 2001). "State Test Scores Reveal Little About School If Too Few Students Take Exams". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Boone, Kevin (May 10, 2001). "Beaumont Sprinter Turns in a 10.2 in the 100 - Payton's Time is Fastest in the Nation This Year". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Wagman, Jake (May 28, 2003). "Top Grads Say Beaumont Helped Them Soar". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- STUDENT PROBABLY WILL BE CHARGED AFTER BRINGING LOADED GUN TO HIGH SCHOOL, OFFICIALS SAY St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO) – Saturday, September 27, 2003 Author: Jake Wagman

- METROPOLITAN AREA DIGEST St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO) – Saturday, June 11, 2005

- KSDKFire at Beaumont High School investigated by bomb and arson squad 12:47 pm, November 19, 2008

- City schools open with optimism and some glitches Enrollment in the district is down by almost 2,000 students. St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO) – Tuesday, August 21, 2007 Author: Steve Giegerich

- Investigators: Fire Intentionally Set at Beaumont High School KSDK 11:31 am, October 10, 2008 http://www.ksdk.com/news/local/story.aspx?storyid=157198&catid=3

- STRUGGLE AGAINST SEGREGATION GOES ON – MANY STILL GO TO SCHOOL WITH THOSE WHO LOOK LIKE THEM St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO) – Sunday, May 16, 2004 Author: Story By Jake Wagman

- TAKING MANNERS INTO OWN HANDS Boys don ties, exude courtesy and adopt self-control via clubs at some city schools. St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO) – Monday, February 26, 2007 Author: Steve Giegerich

- NYT Planning a Path Through Life on the Walk to School April 22, 2007 by Dan Barry

- which emphasizes real-world experiences. St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO) – Wednesday, October 28, 2009 Author: Jane Coaston

- St. Louis Public Schools: Beaumont High School Archived July 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- STLPD Shawn Clubb New principals come to 28 city schools August 3, 2009

- "St. Louis Public Schools: Budget Presentation 2011–2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- STL Public Radio: Budget of schools

- Dan Dillon, Where'd You Go to High School Vol 2., p. 13.

- MSHSAA: Beaumont

- MSHSAA: Championship Histories by Sport

- Beaumont High School, National Center for Education Statistics, retrieved July 29, 2011

- Student Demographics, Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, November 5, 2010, archived from the original on January 9, 2009, retrieved July 29, 2011

- The discipline incident rate is calculated by the number of incidents resulting in a removal from school for ten or more days divided by the number of students in the school.

- Missouri DESE: Remedial coursework

- Missouri DESE: Grade point averages

- Gene F. Barth Dies; Was NFL Official For 20 Years St. Louis Post-Dispatch – October 13, 1991

- Kansas City Star (April 2001). George Brett: a Royal Hero. ISBN 9781582613376., 5.

- Kenneth Charles Iman Obituary.

- Dodge, Andrew R. (2005). Biographical Directory of the United States Congress: 1774–2005. ISBN 9780160731761., 1358.

- BEARS DRAFT MISSOURI'S MOORE AS NO. 1 – Chicago Tribune – January 29, 1971

- Rosenbaum, Jason (June 30, 2015). "Pierson will jump into scramble for Missouri lieutenant governor". KWMU. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- Crippen, Kenneth R. (November 10, 2009). The Original Buffalo Bills. ISBN 9780786446193., 278.

- Porter, David L. (2000). Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Q-Z. ISBN 9780313311765., 1415.

- Sandweiss, Lee Ann (2000). Seeking St. Louis: Voices from a River City, 1670–2000. ISBN 9781883982119., 1031.

- COURTING CHANGE: MISSOURI IS GETTING ITS FIRST BLACK CHIEF JUSTICE – RONNIE WHITE TAKES POST THIS WEEK St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO) – Monday, June 30, 2003 Author: Virginia Young

- "St. Louis Walk of Fame: Wickes". Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- Feldmann, Doug (March 15, 2007). El Birdos: The 1967 and 1968 St. Louis Cardinals. ISBN 9780786455355., 170.

- Lossos, David A. (2004). Irish St. Louis. Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. ISBN 9780738532226., 54.

External links

- Part of A City Decides, the 1955 documentary film about integration in St. Louis