Beauty and the Beast

Beauty and the Beast (French: La Belle et la Bête) is a fairy tale written by French novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve and published in 1740 in La Jeune Américaine et les contes marins (The Young American and Marine Tales).[1] Its lengthy version was abridged, rewritten, and published by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont in 1756 in Magasin des enfants[2] (Children's Collection) to produce the version most commonly retold[1] and later by Andrew Lang in the Blue Fairy Book of his Fairy Book series in 1889. It was influenced by Ancient Greek stories such as "Cupid and Psyche", The Golden Ass, written by Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis in the 2nd century AD, and The Pig King, an Italian fairytale published by Giovanni Francesco Straparola in The Facetious Nights of Straparola around 1550.[3]

| Beauty and the Beast | |

|---|---|

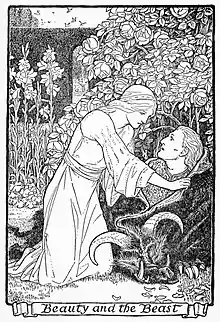

Beauty releases the prince from his beastly curse. Artwork from Europa's Fairy Book, by John Batten | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Beauty and the Beast |

| Also known as | Die Schöne und das Biest |

| Data | |

| Aarne-Thompson grouping | ATU 425C (Beauty and the Beast) |

| Region | France |

| Published in | La jeune américaine, et les contes marins (1740), by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve; Magasin des enfants (1756), by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont |

| Related | Cupid and Psyche (ATU 425B) East of the Sun and West of the Moon (ATU 425A) |

Variants of the tale are known across Europe.[4] In France, for example, Zémire and Azor is an operatic version of the story, written by Marmontel and composed by Grétry in 1771, which had enormous success into the 19th century.[5] Zémire and Azor is based on the second version of the tale. Amour pour amour (Love for love), by Pierre-Claude Nivelle de La Chaussée, is a 1742 play based on de Villeneuve's version. According to researchers at universities in Durham and Lisbon, the story originated about 4,000 years ago.[6]

Plot

Villeneuve's version

A widower merchant lives in a mansion with his twelve children (six sons and six daughters). All of his daughters are very beautiful, but the youngest, Beauty, is the most lovely. She is also kind, well-read, and pure of heart; her elder sisters, though, are cruel, selfish, vain, and spoiled. On a dark and stormy night at sea, the merchant is robbed by pirates who sink most of his merchant fleet and force the entire family to live in a country house and work for a living. While Beauty makes a firm resolution to adjust to rural life with a cheerful disposition, her sisters do not and mistake her firmness for insensibility, forcing her into doing household work in an effort to make enough money to buy back their former home.

A year later, the merchant hears from one of his crew members that one of the trade ships he had sent has arrived back in port, having escaped the destruction of its companions. Before leaving, he asks his children if they wish for him to bring any gifts back for them. The sons ask for weaponry and horses to hunt with, whereas the oldest daughters ask for clothing, jewels, and fine dresses, as they think his wealth has returned. Beauty asks nothing but her father's safety, but when he insists on buying her a present, she is satisfied with the promise of a rose after none had grown last spring. However, to his dismay, the merchant finds that his ship's cargo has been seized to pay his debts, leaving him penniless and unable to buy his children's presents.

On his way back, the merchant is caught in a terrible storm. Seeking shelter, he comes upon a mysterious palace. The merchant sneaks in, seeing that nobody is home, and finds tables laden with food and drinks which seem to have been left for him by the palace's invisible owner. The merchant accepts these gifts and spends the night. The next morning, the merchant sees the palace as his own possession and is about to leave when he sees a rose garden and recalls that Beauty had desired a rose. The merchant quickly plucks the loveliest rose he can find, and is about to pluck more for a bouquet, but is confronted by a hideous "Beast" who warns him that theft of his property (i.e., the rose) is a charge punishable by death. Realizing his deadly mistake, the merchant begs for forgiveness, revealing that he had only picked the rose as a gift for his youngest daughter. After listening to his story, the Beast reluctantly agrees to let him give the rose to Beauty, but only if the merchant brings Beauty to him in exchange without deception; he makes it clear that Beauty must agree to take his place so he can treat her as his fiancée, and not his prisoner, while under no illusions about her predicament. Otherwise, the Beast will destroy his entire family.

At first, the merchant is upset about Beauty being abducted into marrying him, but he reluctantly accepts. The Beast sends him on his way atop a magical horse along with wealth, jewels and fine clothes for his sons and daughters, but stresses that Beauty must never know about his deal. The merchant, upon arriving home, tries to hide the secret from his children, but Beauty pries it from him on purpose. Reacting swiftly, the brothers suggest they could go to the castle and fight the Beast together while the older sisters place blame on Beauty for dooming the entire family. To release her father from the engagement, Beauty volunteers to go to the Beast willingly, and her father reluctantly allows her to go.

Once she arrives at his palace, the Beast is excited to meet Beauty face to face, so he throws a welcome ceremony by treating her to an amazing cabaret. He gives her lavish clothing and food and carries on lengthy conversations with her in which she notes that he is inclined to stupidity rather than savagery. Every night, the Beast asks Beauty to sleep with him, only to be refused each time. After each refusal, Beauty dreams of dancing with a handsome prince. Suddenly, a fairy appears and pleads with Beauty to say why she keeps refusing him. She replies that she doesn't know how to love the Beast because she loves him only as a friend. Despite the apparition of the fairy urging her not to be deceived by appearances, she does not make the connection between a "prince" and a "beast" and becomes convinced that the Beast is holding the Prince captive somewhere in his castle. She searches and discovers many enchanted rooms ranging from libraries to aviaries to enchanted windows allowing her to attend the theater. She also finds live furniture and other live objects which act as servants, but never the Prince from her dreams.

For a month, Beauty lives a life of luxury at the Beast's palace with no end to riches or amusements and an endless supply of exquisite finery to wear. Eventually, she becomes homesick and begs the Beast to allow her to go see her family again. He allows it on the condition that she returns in exactly two months. Beauty agrees to this and is presented with an enchanted ring which will take her back to the Beast when the two months are up. The rest of her family is surprised to find her well fed and dressed in finery. At first, her father advises Beauty to marry the Beast, but when Beauty refuses, her father and her brothers do all they can to detain her return to the Beast. However, Beauty is determined to honor the deal she made.

When the two months are almost up, Beauty begins hallucinating the Beast lying dead in his quarters and uses her ring to return to the Beast. Once she is back in the castle, Beauty's fears are confirmed as she finds out that the Beast died of shame due to her choice of staying with her family permanently after her first trip to his castle. Completely devastated over the wrong choice she made, Beauty bursts into tears and laments that she should have learned how to love the Beast in the first place, screaming, "I am sorry! This was all my fault!". Suddenly, when she says those words, the Beast is transformed into the handsome prince from Beauty's dreams. The Prince informs her that long ago, a powerful witch turned him into a hideous beast for his selfishness after trying to seduce him and that only by finding true love, despite his ugliness, could the curse be broken. He and Beauty are married and they live happily ever after.

Beaumont's version

Beaumont greatly pared down the cast of characters and pruned the tale to an almost archetypal simplicity.[7] The story begins in much the same way, although now the merchant has only six children: three sons and three daughters of which Beauty is one. The circumstances leading to her arrival at the Beast's castle unfold in a similar manner, but on this arrival, Beauty is informed that she is a mistress and he will obey her. Beaumont strips most of the lavish descriptions present in Beauty's exploration of the palace and quickly jumps to her return home. She is given leave to remain there for a week, and when she arrives, her sisters feign fondness to entice her to remain another week in hopes that the Beast will devour her in anger. Again, she returns to him dying and restores his life. The two then marry and live happily ever after.

Variants

The tale is one of the most popular in oral tradition.

France

Emmanuel Cosquin collected a version with a tragic ending from Lorraine titled The White Wolf (Le Loup blanc), in which the youngest daughter asks her father to bring her a singing rose when he returns. The man cannot find a singing rose for his youngest daughter, and he refuses to return home until he finds one. When he finally finds singing roses, they are in the castle of the titular white wolf, who initially wants to kill him for daring to steal his roses, but, upon hearing about his daughters, changes his mind and agrees to spare him his life under the condition he must give him the first living being that greets him when he returns home. This turns out to be his youngest daughter. In the castle, the girl discovers that the white wolf is enchanted and can turn into a human at night, but she must not tell anyone about it. Unfortunately, the girl is later visited by her two elder sisters who pressure her to tell them what is happening. When she finally does, the castle crumbles and the wolf dies.[8]

Henri Pourrat collected a version from Auvergne in south-central France, titled Belle Rose (sometimes translated in English as Lovely Rose). In this version, the heroine and her sisters are the daughters of a poor peasant and are named after flowers, the protagonist being Rose and her sisters Marguerite (Daisy) and Julianne, respectively. The Beast is described as having a mastiff jaw, lizard legs and a salamander's body. The ending is closer to Villeneuve's and Beaumont's versions with Rose rushing back to the castle and finding the Beast lying dead beside a fountain. When the Beast asks if she knows that he can't live without her, Rose answers yes, and the Beast turns into a human. He explains to Rose that he was a prince cursed for mocking a beggar and could only be disenchanted by a poor but kind-hearted maiden. Unlike in Beaumont's version, it is not mentioned that the protagonist's sisters are punished at the end.[9]

Italy

The tale is popular in the Italian oral tradition. Christian Schneller collected a variant from Trentino titled The Singing, Dancing and Music-making Leaf (German: Vom singenden, tanzenden und musicirenden Blatte; Italian: La foglia, che canta, che balla e che suona) in which the Beast takes the form of a snake. Instead of going to visit her family alone, the heroine can only go to her sister's wedding if she agrees to let the snake go with her. During the wedding, they dance together, and when the girl kicks the snake's tail, he turns into a beautiful youth, who is the son of a count.[10]

Sicilian folklorist Giuseppe Pitrè collected a variant from Palermo titled Rusina 'Mperatrici (The Empress Rosina).[11] Domenico Comparetti included a variant from Montale titled Bellindia, in which Bellindia is the heroine's name, while her two eldest sisters are called Carolina and Assunta.[12] Vittorio Imbriani included a version titled Zelinda and the Monster (Zelinda e il Mostro), in which the heroine, called Zelinda, asks for a rose in January. Instead of going to visit her family, staying longer than she promised, and then returning to the Monster's castle to find him dying on the ground, here the Monster shows Zelinda her father dying on a magic mirror and says the only way she can save him is saying that she loves him. Zelinda does as asked, and the Monster turns into a human, who tells her he is the son of the King of the Oranges.[13] Both Comparetti's and Imbriani's versions were included in Sessanta novelle popolari montalesi by Gherardo Nerucci.

British folklorist Rachel Harriette Busk collected a version from Rome titled The Enchanted Rose-Tree where the heroine does not have any sisters.[14] Antonio De Nino collected a variant from Abruzzo, in eastern Italy, that he also titled Bellindia, in which instead of a rose, the heroine asks for a golden carnation. Instead of a seeing it on a magic mirror, or knowing about it because the Beast tells her, here Bellinda knows what happens in her father's house because in the garden there is a tree called the Tree of Weeping and Laughter, whose leaves turn upwards when there is joy in her family, and they drop when there is sorrow.[15]

Francesco Mango collected a Sardianian version titled The Bear and the Three Sisters (S'urzu i is tres sorris), in which the Beast has the form of a bear.[16]

Italo Calvino included a version on Italian Folktales titled Bellinda and the Monster, inspired mostly from Comparetti's version, but adding some elements from De Nino's, like the Tree of Weeping and Laughter.

Spain

Manuel Milá y Fontanals collected a version titled The King's Son, Disenchanted (El hijo del rey, desencantado). In this tale, when the father asks his three daughters what they want, the youngest asks for the hand of the king's son, and everybody thinks she is haughty for wanting such a thing. The father orders his servants to kill her, but they spare her and she hides in the woods. There, she meets a wolf that brings her to a castle and takes her in. The girl learns that in order to break his spell, she must kill the wolf and throw his body into the fire after opening it. From the body flies a pigeon, and from the pigeon an egg. When the girl breaks the egg, the king's son comes out.[17] Francisco Maspons y Labrós extended and translated the tale to Catalan, and included it in the second volume of Lo Rondallayre.[18]

Maspons y Labrós collected a variant from Catalonia titled Lo trist. In this version, instead of roses, the youngest daughter asks for a coral necklace. Whenever one of her family members is sick, the heroine is warned by the garden (a spring with muddy waters; a tree with withered leaves). When she visits her family, she is warned that she must return to the castle if she hears a bell ringing. After her third visit to her family, the heroine returns to the garden where she finds her favorite rosebush withered. When she plucks a rose, the beast appears and turns into a beautiful youth.[19]

A version from Extremadura, titled The Bear Prince (El príncipe oso), was collected by Sergio Hernández de Soto and shows a similar introduction as in Beaumont's and Villeneuve's versions: the heroine's father loses his fortune after a shipwreck. When the merchant has the chance to recover his wealth, he asks his daughters what gift they want from his travels. The heroine asks for a lily. When the merchant finds a lily, a bear appears, saying that his youngest daughter must come to the garden because only she can repair the damage the merchant has caused. His youngest daughter seeks the bear and finds him lying on the ground, wounded. The only way to heal him is by restoring the lily the father took, and when the girl restores it, the bear turns into a prince.[20] This tale was translated to English by Elsie Spicer Eells and retitled The Lily and the Bear.[21]

Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa Sr. collected a version from Almenar de Soria titled The Beast of the Rose Bush (La fiera del rosal), in which the heroine is the daughter of a king instead of a merchant.[22]

Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa Jr. published a version from Sepúlveda, Segovia titled The Beast of the Garden (La fiera del jardín). In this version, the heroine has a stepmother and two stepsisters and asks for an unspecified white flower.[23]

Portugal

In a Portuguese version collected by Zófimo Consiglieri Pedroso, the heroine asks for "a slice of roach off a green meadow". The father finally finds a slice of roach off a green meadow in a castle that appears to be uninhabited, but he hears a voice saying he must bring his youngest daughter to the palace. While the heroine is at the palace, the same unseen voice informs her of the goings-on at her father's house using birds as messengers. When the heroine visits her family, the master of the castle sends a horse to let her know it is time to return. The heroine must go after hearing him three times. The third time she goes to visit her family, her father dies. After the funeral, she's tired and oversleeps, missing the horse's neigh repeat three times before it leaves. When she finally returns to the castle, she finds the beast dying. With his last breath, he curses her and her entire family. The heroine dies a few days after, and her sisters spend the rest of their lives in poverty.[24]

Another Portuguese version from Ourilhe, collected by Francisco Adolfo Coelho and titled A Bella-menina, is closer to Beaumont's tale in its happy ending – the beast is revived and disenchanted.[25]

Belgium and the Netherlands

In a Flemish version from Veurne titled Rose without Thorns (Roosken zonder Doornen), the prince is disenchanted differently than in Beaumont's and Villeneuve's versions. The heroine and the monster attend each of the weddings of the heroine's elder sisters, and to break the spell, the heroine has to give a toast for the beast. In the first wedding, the heroine forgets, but in the second she remembers, and the beast becomes human.[26]

Another Flemish version from Wuustwezel, collected by Victor de Meyere, is closer to Beaumont's plot, the merchant's youngest daughter staying one day more at her family's home and soon returning to the Beast's palace. When she returns, she fears something bad has happened to him. This one is one of the few versions in which the merchant accompanies his daughter back to the Beast's castle.[27]

More similar Beaumont's plot is a Dutch version from Driebergen titled Rozina. In this version, it's Rozina's vow to marry the Beast that eventually breaks the spell.[28][29]

Germany and Central Europe

The Brothers Grimm originally collected a variant of the story, titled The Summer and Winter Garden (Von dem Sommer- und Wintergarten).[30] Here, the youngest daughter asks for a rose in the winter, so the father only finds one a garden that is half eternal winter and half eternal summer. After making a deal with the beast, the father does not tell her daughters anything. Eight days later, the beast appears in the merchant's house and takes his youngest daughter away. When the heroine returns home, her father is ill. She cannot save him, and he dies. The heroine stays longer for her father's funeral, and when she finally returns, she finds the beast lying beneath a heap of cabbages. After the daughter revives the beast by pouring water over him, he turns into a handsome prince.[31] The tale appeared in Brothers Grimm's collection's first edition, in 1812, but because the tale was too similar to its French counterpart, they omitted it in the next editions.

Despite the other folklorists collecting variants from German-speaking territories, Ludwig Bechstein published two versions of the story. In the first, Little Broomstick (Besenstielchen), the heroine, Nettchen, has a best friend called Little Broomstick because her father is a broommaker. Like in The Summer and Winter Garden, Nettchen asks for roses in the dead of winter, which her father only finds in the Beast's garden. When a carriage comes to bring Nettchen to the Beast's castle, Nettchen's father sends Little Broomstick, who pretends to be Nettchen. The Beast discovers the scheme, sends Little Broomstick back home, and Nettchen is sent to the Beast's castle. The prince is disenchanted before Nettchen's visit to her family to cure her father using the sap of a plant from the prince's garden. Jealous of her fortune, Nettchen's sisters drown her in the bath, but Nettchen is revived by the same sorceress who cursed the prince. Nettchen's eldest sisters are too dangerous, but Nettchen doesn't want them dead, so the sorceress turns them into stone statues.[32]

In Bechstein's second version, The Little Nut Twig (Das Nußzweiglein), the heroine asks for the titular twig. When the father finally finds it, he has to make a deal with a bear, promising him the first creature that he meets when he arrives at home. This turns out to be his youngest daughter. Like in Little Broomstick, the merchant tries to deceive the bear by sending another girl, but the bear discovers his scheme and the merchant's daughter is sent to the bear. After she and the bear cross twelve rooms of disgusting creatures, the bear turns into a prince.[33][34]

Carl and Theodor Colshorn collected two versions from Hannover. In the first one, The Clinking Clanking Lowesleaf (Vom klinkesklanken Löwesblatt), the heroine is the daughter of a king. She asks for the titular leaf, which the king only gets after making a deal with a black poodle, promising to give him the first person that greets the king when he arrives home. This turns out to be his youngest daughter. The merchant tries to trick the poodle, giving him other girls pretending to be the princess, but the poodle sees through this. Finally, the princess is sent to the poodle, who brings her to a cabin in the middle of the woods, where the princess feels so alone. She wishes for company, even if it is an old beggar woman. In an instant, an old beggar woman appears, and she tells the princess how to break the spell in exchange for inviting her to the princess' wedding. The princess keeps her promise, and her mother and sisters, who expressed disgust at the sight of the old beggar woman, become crooked and lame.[35]

In Carl and Theodor Colshorn's second version, The Cursed Frog (Der verwunschene Frosch), the heroine is a merchant's daughter. The enchanted prince is a frog, and the daughter asks for a three-colored rose.[36][37]

Ernst Meier collected a version from Swabia, in southwestern Germany, in which the heroine has only one sister instead of two.[38]

Ignaz and Josef Zingerle collected an Austrian variant from Tannheim titled The Bear (Der Bär) in which the heroine is the eldest of the merchant's three daughters. Like in The Summer and Winter Garden and Little Broomstick, the protagonist asks for a rose in the middle of winter.[39] Like in Zingerle's version, the Beast is a bear.

In the Swiss variant, The Bear Prince (Der Bärenprinz), collected by Otto Sutermeister, the youngest daughter asks for grapes.[40]

Scandinavia

Evald Tang Kristensen collected a Danish version that follows Beaumont's version almost exactly. The most significant difference is that the enchanted prince is a horse.[41]

In a version from the Faroe Islands, the youngest daughter asks for an apple instead of a rose.[42][43]

Russia and Eastern Europe

Alexander Afanasyev collected a Russian version, The Enchanted Tsarevich (Заклятый царевич), in which the youngest daughter draws the flower she wants her father to bring her. The beast is a three-headed winged snake.

In a Ukrainian version, both the heroine's parents are dead. The Beast, who has the form of a snake, gives her the ability to revive people.[44]

An apple also plays a relevant role when the heroine goes to visit her family in a Polish version from Mazovia, in this case to warn the heroine that she is staying longer than she promised.[45]

In another Polish version from Kraków, the heroine is called Basia and has a stepmother and two stepsisters.[46] In a Czech variant, the heroine's mother plucks the flower and makes the deal with the Beast, who is a basilisk, who the heroine later will behead to break the spell.[47][48]

In a Moravian version, the youngest daughter asks for three white roses, and the Beast is a dog;[49]

In another Moravian version, the heroine asks for a single red rose and the Beast is a bear.[50]

The Beast is also a bear in a Slovakian variant titled The Three Roses (Trojruža), collected by Pavol Dobšinský, in which the youngest daughter asks for three roses on the same stem.[51]

In a Slovenian version from Livek titled The Enchanted Bear and the Castle (Začaran grad in medved), the heroine breaks the spell reading about the fate of the enchanted castle in an old dusty book.[52]

In a Hungarian version titled The Speaking Grapes, the Smiling Apple and the Tinkling Apricot (Szóló szőlő, mosolygó alma, csengő barack), the Beast is a pig, and the king agrees to give him his youngest daughter's hand in marriage if the pig is capable of moving the king's carriage, which is stuck in the mud.[53]

Greece and Mediterranean Area

In a version from the island of Zakynthos in Western Greece, the prince is turned into a snake by a nereid whom he rejected.[54]

The prince is also turned into a snake in a version from Cyprus in which he is cursed by an orphan who was his lover. In the end, the heroine's elder sisters are turned into stone pillars.[55][56]

Eastern Asia

North American missionary Adele M. Fielde collected a version from China titled The Fairy Serpent, in which the heroine's family is visited by wasps until she follows the beast, who is a serpent. One day, the well she usually fetches water from is dry, so she walks to a spring. When the heroine returns, she finds the snake dying and revives him plunging him in the water. This turns him into a human.[57]

In a second Chinese variant, The King of the Snakes, the Prince of Snakes sees an old man plucking flowers in the Prince's gardens and, irritated, demands the old man sends one of his daughters to him. The youngest, Almond Blossom, being the "most devotedly filial", offers to go in her father's place.[58]

In a third Chinese variant, Pearl of the Sea, the youngest daughter of rich merchant Pekoe asks for a chip of The Great Wall of China because of a dream she had. Her father steals a chip and is threatened by an army of Tatars who work for their master. In reality, the Tatar master is her uncle Chang, who has been enchanted prior to the story, and could only be released from his curse until a woman consented to live with him in the Great Wall.[59]

Southeast Asia

North America

William Wells Newell published an Irish American variant simply titled Rose in the Journal of American Folklore. In this version, the Beast takes the form of a lion.[60]

Marie Campbell collected a version from the Appalachian Mountains, titled A Bunch of Laurela Blooms for a Present, in which the prince was turned into a frog.[61]

Joseph Médard Carrière collected a version in which the Beast is described having a lion's head, horse legs, a bull's body and a snake's tail. Like the end of Beaumont's version, Beauty's sisters are turned into stone statues.[62]

South and Central America

Lindolfo Gomes collected a Brazilian version titled A Bela e a Fera in which the deal consists of the father promising to give the Beast the first living creature that greets him at home. The heroine later visits her family because her eldest sister is getting married.[63]

Mexican linguist Pablo González Casanova collected a version from the Nahuatl titled La doncella y la fiera, in which after returning to her family's home, the heroine finds the beast dead on the ground. The girl falls asleep by his side, and she dreams of the beast, who tells her to cut a specific flower and spray its water on his face. The heroine does so, and the beast turns into a beautiful young man.[64][65]

Broader themes

Harries identifies the two most popular strands of fairy tale in the 18th century as the fantastical romance for adults and the didactic tale for children.[66] Beauty and the Beast is interesting as it bridges this gap, with Villeneuve's version being written as a salon tale for adults and Beaumont's being written as a didactic tale for children.

Commentary

Tatar (2017) compares the tale to the theme of "animal brides and grooms" found in folklore throughout the world,[67] pointing out that the French tale was specifically intended for the preparation of young girls in 18th century France for arranged marriages.[68] The urban opening is unusual in fairy tales, as is the social class of the characters, neither royal nor peasants; it may reflect the social changes occurring at the time of its first writing.[69]

Hamburger (2015) points out that the design of the Beast in the 1946 film adaptation by Jean Cocteau was inspired by the portrait of Petrus Gonsalvus, a native of Tenerife who suffered from hypertrichosis, causing an abnormal growth of hair on his face and other parts, and who came under the protection of the French king and married a beautiful Parisian woman named Catherine.[70]

Modern uses and adaptations

The tale has been notably adapted for screen, stage, prose, and television over many years.

Literature

- The Scarlet Flower (1858), a Russian fairy tale by Sergey Aksakov.

- Beauty and the Beast ... The Story Retold (1886), by Laura E. Richards.

- Beauty: A Retelling of the Story of Beauty and the Beast (1978), by Robin McKinley.

- Rose Daughter (1997), by Robin McKinley.

- The Courtship of Mr. Lyon (1979), from Angela Carter's The Bloody Chamber, based on Madame Le Prince de Beaumont's version.[71]

- Beauty (1983), a short story by Tanith Lee, a science fiction retelling of Beauty and the Beast.

- Fashion Beast, a 1985 screenplay by Alan Moore, adapted into a graphic novel in 2012.

- A Grain of Truth (1993), a short story by Andrzej Sapkowski in The Last Wish.

- Lord of Scoundrels (1995), by Loretta Chase, a Regency romance and retelling of Beauty and the Beast.[72]

- The Fire Rose (1995), by Mercedes Lackey.

- The Quantum Rose, by Catherine Asaro, a science fiction retelling of Beauty and the Beast.

- Beastly (2007), by Alex Flinn, a version that sets the story in modern-day Manhattan.

- Bryony and Roses (2015), by T. Kingfisher (pen name of Ursula Vernon)

- Belle: An Amish Retelling of Beauty and the Beast (2017), by Sarah Price

- A Court of Thorns and Roses (2015), by Sarah J. Maas

- A Curse So Dark and Lonely (2019), by Brigid Kemmerer

Film

- La Belle et la Bête (1946), directed by Jean Cocteau, starring Jean Marais as the Beast and Josette Day as Beauty.[73]

- The Scarlet Flower (1952), an animated feature film directed by Lev Atamanov and produced at the Soyuzmultfilm.

- Beauty and the Beast (1962), directed by Edward L. Cahn, starring Joyce Taylor and Mark Damon.[74]

- Panna a netvor (1978), a Czech film directed by Juraj Herz.

- Beauty and the Beast (1987), a musical live-action version directed by Eugene Marner, starring John Savage as Beast, and Rebecca De Mornay as Beauty.[75]

- Beauty and the Beast (1991), an animated film produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation and directed by Kirk Wise and Gary Trousdale, with a screenplay by Linda Woolverton, and songs by Alan Menken and Howard Ashman.[76]

- Blood of Beasts (2005), a Viking period film directed by David Lister alternately known as Beauty and the Beast.[77]

- Spike (2008), directed by Robert Beaucage, a dark version of the fairy tale updated to modern times.[78]

- Beastly (2011), directed by Daniel Barnz and starring Alex Pettyfer as the beast (named Kyle) and Vanessa Hudgens as the love interest.[79]

- Beauty and the Beast, (2014), a French-German film.[80]

- Beauty and the Beast (2017), a Disney live-action adaptation of the 1991 animated film, starring Emma Watson and Dan Stevens.[81]

Television

- Beauty and the Beast (1976), a made-for-television movie starring George C. Scott and Trish Van Devere.

- "Beauty and the Beast" (1984), an episode of Shelley Duvall's Faerie Tale Theatre, starring Klaus Kinski and Susan Sarandon.

- Beauty and the Beast (1987), a television series which centers around the relationship between Catherine (played by Linda Hamilton), an attorney who lives in New York City, and Vincent (played by Ron Perlman), a gentle but lion-faced "beast" who dwells in the tunnels beneath the city.

- Grimm's Fairy Tale Classics episode "Beauty and the Beast (The Story of the Summer Garden and the Winter Garden)" (1988), in which the Beast has an ogre-like appearance.

- Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child (1995), episode "Beauty and the Beast", featuring the voices of Vanessa L. Williams and Gregory Hines. The Beast is depicted as having a rhinoceros head, a lion-like mane and tail, a humanoid body, and a camel-like hump.

- Stories from My Childhood, episode "Beauty and the Beast (A Tale of the Crimson Flower)" (1998), featuring the voices of Amy Irving as the Beauty, Tim Curry as the Beast, and Robert Loggia as Beauty's father.

- Beauty & the Beast (2012), a reworking of the 1987 TV series starring Jay Ryan and Kristin Kreuk.

- Once Upon a Time episode "Skin Deep" (2012), starring Emilie de Ravin and Robert Carlyle.

- Beauty and the Beast (2014), an Italian/Spanish two-part miniseries starring Blanca Suárez and Alessandro Preziosi.

- Sofia the First episode "Beauty is the Beast" (2016), in which Princess Charlotte of Isleworth (voiced by Megan Hilty) is turned into a beast (a cross between a human and a wild boar with a wolf-like tail) by a powerful enchantress.

Theatre

- La Belle et la Bête (1994), an opera by Philip Glass based on Cocteau's film. Glass's composition follows the film scene by scene, effectively providing a new original soundtrack for the movie.[82]

- Beauty and the Beast (1994), a musical adaptation of the Disney film by Linda Woolverton and Alan Menken, with additional lyrics by Tim Rice.[83]

- Beauty and the Beast (2011), a ballet choreographed by David Nixon for Northern Ballet, including compositions by Bizet and Poulenc.[84]

Other

- A hidden object game, Mystery Legends: Beauty and the Beast, was released in 2012.[85]

- The hidden object game series Dark Parables based the main story of 9th game (The Queen of Sands) on the tale.

- The narrative of the Sierra Entertainment adventure game King's Quest VI follows several fairy tales, and Beauty and the Beast is the focus of one multiple part quest.[86]

- Stevie Nicks recorded "Beauty and the Beast" for her 1983 solo album, The Wild Heart.

- Real Life based the video for their signature hit "Send Me an Angel" on the fairy story.

- Disco producer Alec R. Costandinos released a twelve inch by his side project Love & Kisses with the theme of the fairy-tale set to a disco melody in 1978.

- The interactive fiction work, Bronze by Emily Short, is a puzzle-oriented adaptation of Beauty and the Beast.[87]

References

- Windling, Terri. "Beauty and the Beast, Old and New". The Journal of Mythic Arts. The Endicott Studio. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014.

- Stouff, Jean. "La Belle et la Bête". Biblioweb.

- Harrison, "Cupid and Psyche", Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome',' p. 339.

- Heidi Anne Heiner, "Tales Similar to Beauty and the Beast"

- Thomas, Downing. Aesthetics of Opera in the Ancien Régime, 1647–1785. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2002.

- BBC. "Fairy tale origins thousands of years old, researchers say". BBC News. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- Betsy Hearne, Beauty and the Beast: Visions and Revisions of An Old Tale, p 25 ISBN 0-226-32239-4

- Cosquin, Emmanuel Contes populaires de Lorraine Tome II. Deuxiéme Tirage. Paris: Vieweg 1887 pp. 215-217

- Pourrat, Henri French Folktales New York: Pantheon Books 1989 pp. 447-456

- Schneller, Christian Märchen und Sagen aus Wälschtirol Innsbruck: Wagner 1867 pp. 63-65.

- Pitrè, Giuseppe Fiabe, novelle e racconti popolari siciliane Volume Primo. Palermo: Luigi Pedone Lauriel 1875 pp. 350-356

- Comparetti, Domenico Novelline popolari italiane Roma: Ermanno Loescher. 1875. pp. 274-280.

- Imbriani, Vittorio La Novellaja Fiorentina Livorno: Coi tipi di F. Vigo 1877 pp. 319-327

- Busk, Rachel Harriette The Folk-lore of Rome: collected by Worth of Mouth from People London: Longmans, Green & Co. 1874 pp. 115-118

- De Nino, Antonio Usi e costumi abruzzesi Volume Terzo. Firenze: Tipografia di G. Barbèra 1883 pp. 161-166

- Mango, Francesco Novelline popolari sarde Palermo: Carlo Clausen 1885 pp. 39-41

- Milá y Fontanals Observaciones sobre la poesía popular Barcelona: Imprenta de Narciso Ramirez 1853 pp. 185-186

- Maspons y Labrós, Francisco Lo Rondallayre: Quentos Populars Catalans Vol. II Barcelona: Llibrería de Álvar Verdaguer 1871 pp. 104-110

- Maspons y Labrós, Francisco Lo Rondallayre: Quentos Populars Catalans Vol. I Barcelona: Llibrería de Álvar Verdaguer. 1871. pp. 103-106

- Hernández de Soto, Sergio. Biblioteca de las Tradiciones Populares Españolas. Madrid: Librería de Fernando Fé. 1886. pp. 118-121.

- Eells, Elsie Spicer Tales of Enchantment from Spain. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. 1920. p. 109.

- Espinosa, Aurelio Macedonio Cuentos Populares Españoles Standford University Press. 1924. pp. 271-273

- Espinosa, Aurelio Macedonio Cuentos populares de Castilla y León Volumen 1 Madrid: CSIC 1987 pp. 240-243

- Pedroso, Consiglieri. Portuguese Folk-Tales. New York: Folklore Society Publications. 1882. pp. 41-45.

- Coelho, Adolfo. Contos Populares Portuguezes. Lisboa: P. Plantier. 1879. pp. 69-71.

- Wolf, Johann Wilhelm. Grootmoederken, Archiven voor Nederduitsche Sagen, Sprookjes, Volksliederen, Volksfeesten en Volksgebruiken Gent: Boek en Steendrukkery van C. Annoot-Braeckman. 1842. pp. 61-66.

- De Meyere, Victor De Vlaamsche vertelselschat Deel 2 Antwerpen: De Sikkel 1927 pp. 139.147

- Meder, Theo De magische Vlucht Amsterdan: Bert Bakker 2000 pp. 54-65

- Meder, Theo The Flying Dutchman and Other Folktales from the Netherlands Westport and London: Libraries Unlimited. 2008. pp. 29-37.

- Grimm, Jacob, Wilhelm Grimm, JACK ZIPES, and ANDREA DEZSÖ. "THE SUMMER AND THE WINTER GARDEN." In: The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. pp. 225-27. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014. Accessed 29 August 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctt6wq18v.75.

- Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Kinder- und Hausmärchen Berlin: Realschulbuchhandlung 1812 pp. 323-328

- Bechstein, Ludwig Deutsches Märchenbuch Leipzig: Verlag von Georg Wigand 1847 pp. 228-232

- Bechstein, Ludwig Deutsches Märchenbuch Leipzig: Verlag von Georg Wigand 1847 pp. 81-85

- Bechstein, Ludwig The Old Story-teller: Popular German Tales London: Addey & Co. 1854 pp. 17-22

- Colshorn, Carl and Theodor Märchen und Sagen aus Hannover Hannover: Verlag von Carl Ruempler 1854 pp. 64-69

- Colshorn, Carl and Theodor Märchen und Sagen aus Hannover Hannover: Verlag von Carl Ruempler 1854 pp. 139-141

- Zipes, Jack The Golden Age of Folk and Fairy Tales: From the Brothers Grimm to Andrew Lang Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company 2013 pp. 215-217

- Meier, Ernst Deutsche Volksmärchen aus Schwaben Stuttgart: C.P. Scheitlin 1852 pp. 202-204

- Zingerle, Ignaz und Josef Kinder- und Hausmärchen aus Süddeutschland Regensburg 1854 pp. 310-313

- Sutermeister, Otto Kinder- und Hausmärchen aus der Schweiz Aarau: H.R. Sauerländer 1869 pp. 75-78

- Tang Kristensen, Evald Æventyr fra Jylland Vol. I. Kjobehavn: Trykt hos Konrad Jorgensen i Kolding 1884 pp. 335-340

- Jakobsen, Jakob Færøske folkesagn og æventyr København: S. L. Møllers Bogtrykkeri 1898 pp. 430-438

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm Zweiter Band Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung 1913 p. 242

- Chubynsky, Pavlo Труды этнографическо-статистической экспедиции в Западно-Русский Край TOM 2 St. Petersburg 1878 pp. 444-445

- Zmorski, Roman Podania i baśni ludu w Mazowszu Wrocław: Zygmunta Schlettera 1852 pp. 58-74

- Kolberg, Oskar Lud: Jego zwyczaje, sposób życia, mowa, podania, przysłowia, obrzędy, gusła, zabawy, pieśni, muzyka i tańce Serya VIII Kraków: Ludwika Gumplowicza 1875 pp. 47-48

- Kubín, Josef Štefan Povídky kladské Prague: Společnost Národopisného musea českoslovanského 1908 pp. 130-135

- Baudiš, Josef The Key of Gold: 23 Czech Folk Tales London: George Allen & Unwind Ltd. 1917 pp. 123-128

- Kulda, Beneš Metod Moravské národní pohádky a pověsti z okolí rožnovského Svazek první Prague: I.L. Kober 1874 pp. 148-151

- Mikšíček, Matěj Národní báchorky moravské a slezské Prague: I.L. Kober 1888 pp. 214-220

- Dobšinský, Pavol Prostonárodnie slovenské povesti Sošit 5 1881 pp. 12-18

- Gabršček, Andrej Narodne pripovedke v Soških planinah Vol. II 1894 pp. 33-38

- Jones, W. Henry & Kropf, Lewis L. The Folk-Tales of the Magyars London: Elliot Stock 1889 pp. 131-136

- Schmidt, Bernhard Griechische Märchen, Sagen und Volkslieder Leipzig: Teubner 1877 pp. 88-91

- Liebrecht, Felix Jahrbuch für romanische und englische Literatur Elfter Band Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus 1870 pp. 374-379

- Garnett, Lucy M.J. Greek Folk Poesy vol. II Guildford: Billing and Sons 1896 pp. 152-157

- Fielde, Adele M. Chinese Night Entertaiments New York and London: G. P. Putnam's Sons 1893 pp. 45-41

- Macgowan, John. Chinese folk-lore. Shanghai: North-China Daily News & Herald. 1910. pp. 212-224.

- Goddard, Julia. Fairy tales in other lands. London, Paris, Melbourne: Cassell & Company. 1892. pp. 9-33.

- Newell, William Wells Journal of American Folklore vol. 2 1889 pp. 213-214 American Folklore Society

- Campbell, Marie Tales from the Cloud Walking Country Indiana University Press 1958 pp. 228-230

- Carrière, Joseph Médard Contes du Detroit Sudbury: Prise de parole 2005 pp. 68-981

- Gomes, Lindolfo Contos Populaires Brasileiros São Paulo: Melhoramentos 1931 pp. 185-188

- González Casanova, Pablo Cuentos indígenas Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 2001 pp. 99-95

- Baudot, Georges. "La Belle et la Bête dans le folklore náhuatl du Mexique central". In: Cahiers du monde hispanique et luso-brésilien, n°27, 1976. Hommage à Paul Mérimée. pp. 53-61. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/carav.1976.2049]; www.persee.fr/doc/carav_0008-0152_1976_num_27_1_2049

- Harries, Elizabeth (2003). Twice upon a time: Women Writers and the History of the Fairy Tale. Princeton University Press. p. 80.

- Tatar, Maria (7 March 2017). Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales of Animal Brides and Grooms from Around the World. Random House Penguin. ISBN 9780143111696.

- Gilbert, Sophie (31 March 2017). "The Dark Morality of Fairy-Tale Animal Brides". The Atlantic. Retrieved 31 March 2017. "Maria Tatar points [...] the story of Beauty and the Beast was meant for girls who would likely have their marriages arranged".

- Maria Tatar, p 45, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- Andreas Hamburger in: Andreas Hamburger (ed.) Women and Images of Men in Cinema: Gender Construction in La Belle et La Bete by Jean Cocteauchapter 3 (2015). see also: "La Bella y la Bestia": Una historia real inspirada por un hombre de carne y hueso (difundir.org 2016)

- Crunelle-Vanrigh, Anny. "The Logic of the Same and Différance: 'The Courtship of Mr. Lyon'". In Roemer, Danielle Marie, and Bacchilega, Cristina, eds. (2001). Angela Carter and the Fairy Tale, p. 128. Wayne State University Press.

- Wherry, Maryan (2015). "More than a Love Story: The Complexities of the Popular Romance". In Berberich, Christine (ed.). The Bloomsbury Introduction to Popular Fiction. Bloomsbury. p. 55. ISBN 978-1441172013.

- David J. Hogan (1986). Dark Romance: Sexuality in the Horror Film. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 90. ISBN 0-7864-0474-4.

- "50s and 60s Horror Movies B". The Missing Link. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- Russell A. Peck. "Cinderella Bibliography: Beauty and the Beast". The Camelot Project at the University of Rochester. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- Janet Maslin (13 November 1991). "Disney's 'Beauty and the Beast' Updated in Form and Content". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- Maslin, Janet. "Beauty and the Beast: Overview". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- Calum Waddell. "Spike". Total Sci-Fi. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- Larry Carroll (30 March 2010). "Vanessa Hudgens And Alex Pettyfer Get 'Intense' In 'Beastly'". MTV. Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- http://www.premiere.fr/Cinema/News-Cinema/Christophe-Gans-decrypte-sa-version-de-La-Belle-et-la-Bete

- "Beauty and the Beast (2017)". Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- "Alternate Versions for La Belle et la Bête". IMDb. Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- Tale as Old as Time: The Making of Beauty and the Beast. [VCD]. Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2002.

- Thompson, Laura (19 December 2011). "Beauty and the Beast, Northern Ballet, Grand Theatre, Leeds, review". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- Mystery Legends: Beauty and the Beast Collector's Edition (PC DVD)

- KQ6 Game Play video

- Bronze homepage, including background information and download links

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beauty and Beast. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- "The Story of the Beauty and the Beast", James Planché's translation of Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve's original version of the fairytale, on Project Gutenberg.

- The story of beauty & the beast; the complete fairy story translated from the French by Ernest Dowson on Internet Archive. Ernest Dowson's translation of de Villeneuve's original fairytale.

- "Beauty and the Beast", the revised and abridged version by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, at the website of the University of Pittsburgh.

- "Beauty and the Beast: folktales of Aarne-Thompson type 425C

- Cinderella Bibliography – includes an exhaustive list of B&tB productions in books, TV and recordings

- Original version and psychological analysis of Beauty and the Beast (Archive on Wayback Machine)

- (in French) La Belle et la Bête, audio version