Bethmaus

Bethmaus, or Beth Maʿon (Greek: Βηθμαούς) (Hebrew: בית מעון), was a Jewish village during the late Second Temple and Mishnaic periods, and which was already a ruin (Tell Maʿūn) when Kitchener visited the site in 1877.[1][2] It was situated upon the hill, directly north-west of the old city of Tiberias, at a distance of one biblical mile,[3] rising to an elevation of 250 metres (820 ft) above sea-level. It is now incorporated within the modern city bounds of Upper Tiberias.

Beth Maʿon | |

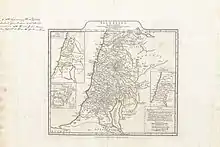

Shown within Mandatory Palestine  Bethmaus (Israel) | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Region | Lower Galilee |

| Coordinates | 32°47′40″N 35°32′00″E |

| Type | village (ruin) |

| History | |

| Periods | Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine |

| Cultures | Jewish |

| Associated with | Jews |

The Midrash (Genesis Rabba § 85:7) says of the village, "Beth Maʿon, they ascend to it from Tiberias, but they go down to it from Kefar Shobtai."[4][5] The Jerusalem Talmud, citing a variant account, says that they would go down to Beth Maʿon from its broad place.[6]

History

Based on the potsherds found in situ, the place was inhabited as early as the Bronze Age and Iron Age.[7]

Josephus, the Jewish general turned historian, mentions that when he was put in charge of the public affairs of Galilee by the people of Jerusalem during the war with Rome, he moved with two of his fellow-legates who were priests of Aaron's lineage from Sepphoris to the village Bethmaus (henceforth: Beth Maʿon), a village situated four furlongs (stadia) distant from Tiberias.[8] It was at Beth Maʿon that Josephus met Justus of Tiberias. There, they convened a meeting with the principal persons of Tiberias, to discuss a plan to demolish a house built by Herod the Tetrarch in Tiberias, and which had the figures of living creatures in it (contrary to Jewish law), but to restore the royal furniture of that house, consisting of candlesticks made of Corinthian brass, and of royal tables, and of a great quantity of uncoined silver, to the king. However, when Josephus took leave of Beth Maʿon and went into Upper Galilee, before Josephus and the senate of Tiberias could carry out their schemes, certain mariners and poor people of Galilee had plundered the house built by Herod of its effects, and taken away the spoils.

In the early 2nd-century CE, following the Bar Kokhba revolt, Beth Maʿon became the residence of one of the priestly clans known as Ḥuppah. Around this time, representatives of the twenty-four priestly wards moved and settled in the Galilee.[9][10] In the 20th-century, three stone inscriptions were discovered bearing the names of the priestly wards, their order and the name of the locality to which they had moved after the destruction of the Second Temple: In 1920, a stone inscription was found in Ashkelon showing a partial list of the priestly wards; in 1962 three small fragments of one Hebrew stone inscription bearing the partial names of places associated with the priestly courses (the rest of which had been reconstructed) were found in Caesarea Maritima, dated to the third-fourth centuries;[11][12] in 1970 a stone inscription was found on a partially buried column in a mosque, in the Yemeni village of Bayt al-Ḥaḍir, showing ten names of the priestly wards and their respective towns and villages. The Yemeni inscription is the longest roster of names of this sort ever discovered unto this day, and mentions the priestly course in Beth Maʿon. The seventh-century poet, Eleazar ben Killir, echoing the same tradition, also wrote a liturgical poem detailing the 24-priestly wards and their places of residence.[13] Historian and geographer, Samuel Klein (1886–1940), thinks that Killir's poem proves the prevalence of this custom of commemorating the courses in the synagogues of Ereẓ Israel.[14] The purpose of composing these lists was to keep in living memory the identities and traditions of each priestly family, in hopes that the Temple would be quickly rebuilt.[15]

In extant Turkish documents dating to May 1566, the Ottoman ruler, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, ordered that water be drawn from Beth Maʿon and brought to Tiberias,[16] the purpose of which is not now known, although thought to have been for agricultural crops. By April 1566, when the work had not yet been completed and the workers (under Don Joseph Nasi) demanded more money from the Sultan to complete the project, the Sultan refused to set aside more money for the project. Below Beth Maʿon, between the ruins of the ancient village and Tiberias, are found two natural springs.

References

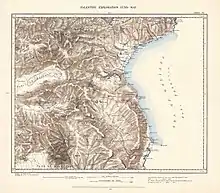

- Conder & Kitchener (1881), p. 371. Tell Maʿūn is shown on the 1880 Survey of Western Palestine map, sheet no. 6.

- Cf. Conder, C.R. (1879), p. 181

- Ishtori Haparchi (2007), p. 56, who makes mention of the village Maʿon, which he describes as being "within a Sabbath day's journey to the west of Tiberias." The editor of the volume has identified the site as Beth Maʿon, mentioned in the Jerusalem Talmud, Sotah 1:8, and Baba Metziah 7:1. Ishtori Haparhi had mistaken this Maʿon in Galilee for being the one where David and his men took refuge from King Saul, in I Samuel 23:24.

- Klein, S. (1939), p. 16

- Neubauer, A. (1868), p. 218

- Original: paloṭetha = perhaps der. of πλατεια ("a broad place"). Above Bethmaus there was an extensive plateau. See Jerusalem Talmud, Sotah 1:8 (7a)

- Yitzhaki, A. (1978). Israel Guide - Lower Galilee and Kinneret Region (A useful encyclopedia for the knowledge of the country) (in Hebrew). 3. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, in affiliation with the Israel Ministry of Defence. p. 216. OCLC 745203905., s.v. Ancient sites in the vicinity of Tiberius: The ruin of Beit Ma'on

- Josephus, Vita § 12, which happens to be the equivalent of a biblical mile.

- Klein, S. (1939), p. 164 (s.v. בית מעון); Klein, S. (1945), p. 65

- Rosenfeld, B. (1998), p. 82 [26]

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1962), pp. 137–139

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1964), pp. 24–28

- Poem entitled, Lamentation for the 9th of Ab, composed in twenty-four stanzas, and the last line of each stanza contains the name of the village where each priestly family lived.

- Klein, S. (1909); Enrico Tuccinardi, Nazareth, the Caesarea Inscription, and the hand of God, (translated from the French by René Salm), Academia, pp. 6–7

- Enrico Tuccinardi, Nazareth, the Caesarea Inscription, and the hand of God, (translated from the French by René Salm), Academia, p. 7

- Heyd, U. (1966), p. 199

Bibliography

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1962). "A List of Priestly Courses from Caesarea". Israel Exploration Journal. 12 (2): 137–139. JSTOR 27924896.

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1964). "The Caesarea Inscription of the Twenty-Four Priestly Courses". Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies (in Hebrew). L.A. Mayer Memorial Volume (1895-1959): 24–28. JSTOR 23614642.

- Conder, C.R. (1879). Tent Work in Palestine - A Record of Discovery and Adventure. 2. London: Richard Bentley & Son.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Heyd, U. (1966). "Turkish Documents on the Rebuilding of Tiberias in the sixteenth century". Sefunot: Studies and Sources on the History of the Jewish Communities in the East. 10: 193–210. JSTOR 23416042.

- Ishtori Haparchi (2007). Avraham Yosef Havatzelet (ed.). Sefer Kaftor Ve'ferah (in Hebrew). 2 (chapter 11). Jerusalem.

- Klein, S. (1909). "Barajta der vierundzwanzig Priester Abteilungen (Baraitta of the Twenty-Four Priestly Divisions)". Beiträge zur Geographie und Geschichte Galiläas (in German).

- Klein, S. (1939). Sefer Ha-Yishuv (The Book of the Yishuv: A treasure of information and records, inscriptions and memoirs, preserved in Israel and in the people in the Hebrew language and in other languages on the settlement of the Land of Israel) (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Bialik Institute.

- Klein, S. (1945). Yehuda Elitzur (ed.). Land of the Galilee: From the Time of Babylonian Immigration until the Redaction of the Talmud (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook.

- Neubauer, A. (1868). Géographie du Talmud (in French). Paris: M. Lévy Frères.

- Rosenfeld, Ben-Zion (1998). "Places of Rabbinic Settlement in the Galilee, 70-400 C.E.: Periphery versus Center". Hebrew Union College Annual. 69: 57–103. JSTOR 23508858.

External links

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 6: IAA, Wikimedia commons