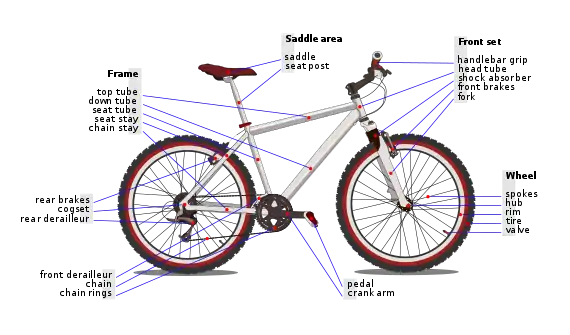

Bicycle drivetrain systems

Bicycle drivetrain systems are used to transmit power on bicycles, tricycles, quadracycles, unicycles, or other human-powered vehicles from the riders to the drive wheels. Most also include some type of a mechanism to convert speed and torque via gear ratios.

History

The history of bicycle drivetrain systems is closely linked to the history of the bicycle. Major changes in bicycle form have often been initiated or accompanied by advances in drivetrain systems. Several early drivetrains used straight-cut gears that meshed directly with each other outside of the hub.[1][2] Some bicycles have used a double-sided rear wheel, with different-sized sprockets on each side. To change gears, the rider would stop and dismount, remove the rear wheel and reinstall it in the reverse direction. Derailleur systems were first developed in the late 19th century, but the modern cable-operated parallelogram derailleur was invented in the 1950s.

Power collection

Bicycle drivetrain systems have been developed to collect power from riders by a variety of methods.

From legs

From arms

From whole body

- Rowing[5]

- Hand and foot[5]

- Exycle: from legs and chest[8]

From multiple riders

Power transmission

Bicycle drivetrain systems have been developed to transmit power from riders to drive wheels by a variety of methods. Most bicycle drivetrain systems incorporate a freewheel to allow coasting, but direct drive and fixed-gear systems do not. The latter are sometimes also described as bicycle brake systems.

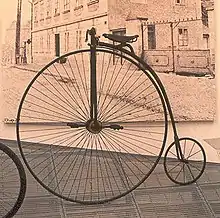

Direct

Some human powered vehicles, both historical and modern, employ direct drive. Examples include most Penny-farthings, unicycles, and children's tricycles.

Another interpretation of direct drive is that the rider pushes directly against the ground with a foot, as employed in balance bicycles, kick scooters, and chukudus.

Non-rotating

Two-wheel drive

In 1991, a two-wheel drive bicycle was marketed under the Legacy name. It used a flexible shaft and two bevel gears to transmit torque from the rear wheel, driven by a conventional bicycle chain with derailleurs, to the front wheel.[11] In 1994, Steve Christini and Mike Dunn introduced a two-wheel drive option.[12] Their AWD system, aimed at mountain bikers, comprises an adapted differential that sends power to the front wheel once the rear begins to slip. In the late 1990s, 2WD 'Dual Power' mountain bikes were sold in Germany under the Subaru name. They used one belt to transfer power from the rear wheel to the head tube, a small gearbox to allow rotation of the front fork, and then a second belt to transfer power to the front wheel.[13]

Speed and torque conversion

A cyclist's legs produce power optimally within a narrow pedalling speed range. Gearing is optimized to use this narrow range as best as possible. Bicycle drivetrain systems have been developed to convert speed and torque by a variety of methods.

Implementation

Several technologies have been developed to alter gear ratios. They can be used individually, as an external derailleur or an internal hub gear, or in combinations such as the SRAM Dual Drive, which uses a standard 8 or 9-speed cassette mounted on a three-speed internally geared hub, offering a similar gear range as a bicycle with a cassette and triple chainrings.

- Derailleur gears

- Hub gear

- Gearbox bicycle

- Retro-Direct

- Lever and cam mechanism, as in the Stringbike

Theory

Single-speed

Integration

While several combinations of power collection, transmission, and conversion exist, not all combinations are feasible. For example, a shaft-drive is usually accompanied by a hub gear, and derailleurs are usually implemented with chain drive.

Gallery

ElliptiGO uses motion similar to that of an elliptical trainer for motion on a modern treadle bicycle

ElliptiGO uses motion similar to that of an elliptical trainer for motion on a modern treadle bicycle Hand crank on a tricycle

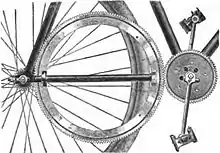

Hand crank on a tricycle Hildick Chainless Bicycle Gear 1898

Hildick Chainless Bicycle Gear 1898 Cable of a row bike

Cable of a row bike

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bicycle drivetrains. |

- Berto, Frank J. (2008) [2000]. The Dancing Chain: History and Development of the Derailleur Bicycle (3rd ed.). Cycle Publishing/Van der Plas Publications. pp. 23–28. ISBN 978-1-892495-59-4. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Berto, Frank J. (2016) [2000]. The Dancing Chain: History and Development of the Derailleur Bicycle (5th ed.). Cycle Publishing/Van der Plas Publications. ISBN 978-1-892495-77-8. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- "3G Stepper Bike: A Fitness Monster that Beats Your Gym Membership". Popular Mechanics. October 1, 2009. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- "A Different Kind Of Bicycle". Gadgetopia. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- Wallack, Roy M. (30 November 2009). "Going Beyond the Basic Bike". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

- Richard Peace (11 Jan 2010). "ElliptiGO seatless bike launched". BikeRadar.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- "Weird Bikes II - More Weird Bike Stuff". Charlie Kelly. Retrieved 2012-07-17.

Here we have not one but TWO examples of bikes that raise and lower the rider during each pedal stroke. On both of these bikes, the rider pedals with his feet together and stands up and sits back down to propel himself.

- "Weird Bikes II - Total Body Bikes". Charlie Kelly. Retrieved 2012-07-17.

Slide the handles in and out as you ride, with the motion transmitted to the front wheel via a system of cords and springs.

- James Huang (September 11, 2014). "The incredible Mando Footloose IM e-bike". Bike Radar. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

There is no mechanical connection between the cranks and rear wheel at all. Instead, the cranks are connected to an alternator, which continually recharges the battery that powers the 250-watt motor at the rear wheel.

- Pete (October 16, 2014). "No Chain?! Mando Footloose IM Series Hybrid Electric Bike". Electric Bike Report. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- "Weird Bike Stuff - Legacy 2 wheel drive!". Charlie Kelly. Retrieved 2012-07-17.

- "Christini background". Elan Ligfietsen. 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-08-21. Retrieved 2012-07-17.

- Michael Embacher (2011). Cyclopedia. Fontaine & Noë / Lannoo. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-90-72975-08-9.