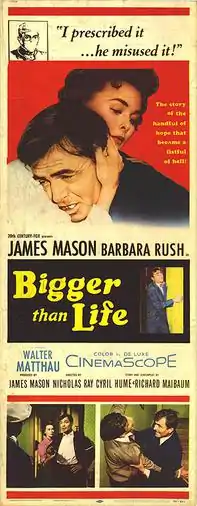

Bigger Than Life

Bigger Than Life is an American film made in 1956 directed by Nicholas Ray and starring James Mason, who also co-wrote and produced the film, about a school teacher and family man whose life spins out of control upon becoming addicted to cortisone.[2] The film co-stars Barbara Rush as his wife and Walter Matthau as his closest friend, a fellow teacher. Though it was a box-office flop upon its initial release,[3] many modern critics hail it as a masterpiece and brilliant indictment of contemporary attitudes towards mental illness and addiction.[4] In 1963, Jean-Luc Godard named it one of the ten best American sound films ever made.[5]

| Bigger Than Life | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Nicholas Ray |

| Produced by | James Mason |

| Screenplay by | Cyril Hume Richard Maibaum |

| Based on | Ten Feet Tall 1955 story in The New Yorker by Berton Roueché |

| Starring | James Mason Barbara Rush Walter Matthau |

| Music by | David Raksin |

| Cinematography | Joseph MacDonald |

| Edited by | Louis R. Loeffler |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million[1] |

Bigger Than Life was based on a 1955 article by medical writer Berton Roueché in The New Yorker, titled "Ten Feet Tall".[6]

Plot

Schoolteacher and family man Ed Avery (James Mason), who has been suffering bouts of severe pain and even blackouts, is hospitalized with what is diagnosed as polyarteritis nodosa, a rare inflammation of the arteries. Told by doctors that he probably has only months to live, Ed agrees to an experimental treatment: doses of the hormone cortisone.

Ed makes a remarkable recovery. He returns home to his wife, Lou (Barbara Rush), and their son, Richie (Christopher Olsen). He must keep taking cortisone tablets regularly to prevent a recurrence of his illness. But the "miracle" cure turns into a nightmare when Ed begins to misuse the tablets, causing him to experience wild mood swings and, ultimately, a psychotic episode which threatens the safety of his family.

Cast

- James Mason as Ed Avery

- Barbara Rush as Lou Avery

- Walter Matthau as Wally Gibbs

- Robert F. Simon as Dr. Norton

- Christopher Olsen as Richie Avery

- Roland Winters as Dr. Ruric

- Rusty Lane as Bob LaPorte

- Rachel Stephens as Nurse

- Kipp Hamilton as Pat Wade

Reception

Bigger Than Life was not a financial success. Mason, who produced the film as well as starring in it, blamed its failure on its use of the relatively new widescreen CinemaScope format.[3] American critics panned the film, considering it melodramatic and heavyhanded.[7] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called it tedious, "dismal", and "more pitiful than terrifying to watch".[8]

However, the film was well received by the influential magazine Cahiers du cinéma. Jean-Luc Godard called it one of the ten best American sound films.[5] Likewise, François Truffaut praised the film, noting the "intelligent, subtle" script, the "extraordinary precision" of Mason's performance, and the beauty of the film's CinemaScope photography.[9]

Modern critics have praised Nicholas Ray's use of widescreen cinematography to depict the interior spaces of a family drama, rather than the open vistas typically associated with the format, as well as his use of extreme close-ups in portraying the main character's psychosis and megalomania.[10] The film is recognized for its multi-layered examination of the American nuclear family in the Eisenhower era. While the film can be read as a straightforward exposé on medical malpractice and the overuse of prescription drugs in modern American society,[11] it has also been seen as a critique of consumerism, the male-dominated traditional family structure, and the claustrophobic conformism of suburban life.[4][12][13] Truffaut saw Ed's drug-influenced speech to the parents of the parent-teacher association as having fascist overtones.[14] The film has also been interpreted as an examination of masculinity and a leftist critique of the low salaries of public school teachers in the United States.[15]

In 1998, Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader included the film in his unranked list of the best American films not included on the AFI Top 100.[16]

References

- Solomon 1989, p. 250.

- DVD of the Week: Bigger Than Life|The New Yorker

- Cossar 2011, p. 273.

- Halliwell 2013, pp. 159-162.

- Marshall, Colin (December 2, 2013). "A Young Jean-Luc Godard Picks the 10 Best American Films Ever Made (1963)". Open Culture.

- Roueché, Berton (September 10, 1955). "Ten Feet Tall". The New Yorker: 47–77.

- Schiebel 2014, p. 183.

- Crowther, Bosley (August 3, 1956). "Screen: Tax of Tedium; 'Bigger Than Life' Has Debut at Victoria". The New York Times.

- Truffaut 2009, pp. 143-147.

- Cossar 2011, pp. 120-123.

- Truffaut 2009, pp. 145–146. Truffaut noted Nicholas Ray's low opinion of the medical profession, and of so-called "miracle drugs". His discussion of Bigger Than Life points out the visual similarity between the doctors in the film and "gangsters in crime films".

- Basinger 2013, pp. 231-234.

- Rosenbaum 1997, pp. 131-133.

- Truffaut & pp-145-146.

- Schiebel 2014, p. 182.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan (June 25, 1998). "List-o-Mania: Or, How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love American Movies". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020.

Sources

- Basinger, Jeanine (2013). I Do and I Don't: A History of Marriage in the Movies. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780307962225.

- Cossar, Harper (2011). Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813126517.

- Halliwell, Martin (2013). Therapeutic Revolutions: Medicine, Psychiatry, and American Culture, 1945-1970. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813560663.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1997). Movies as Politics. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520918108.

- Schiebel, Will (2014). "Bigger Than Life: Melodrama, Masculinity, and the American Dream". In Rybin, Steven; Schiebel, Will (eds.). Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground: Nicholas Ray in American Cinema. SUNY Press. ISBN 9781438449814.

- Solomon, Aubrey (1989). Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History. Scarecrow Press.

- Truffaut, François (2009). The Films In My Life. Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780786749720.

External links

- Bigger Than Life at IMDb

- Bigger Than Life at Rotten Tomatoes

- Bigger Than Life at AllMovie

- Bigger Than Life at the TCM Movie Database

- Bigger Than Life at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Bigger Than Life: Somewhere in Suburbia an essay by B. Kite at the Criterion Collection