Bodyline

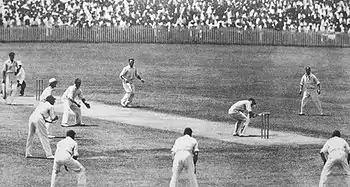

Bodyline, also known as fast leg theory bowling, was a cricketing tactic devised by the English cricket team for their 1932–33 Ashes tour of Australia, created to combat the extraordinary batting skill of Australia's Don Bradman. A bodyline delivery was one in which the cricket ball was bowled at the body of the batsman in the hope that when he defended himself with his bat a resulting deflection could be caught by one of several fielders standing close by.

Critics considered the tactic intimidating and physically threatening to the point of being unfair in a game that was supposed to uphold gentlemanly traditions.[1] England's use of the tactic was perceived by some as overly aggressive or even unfair. It threatened diplomatic relations between the two countries before the situation was calmed.[2][3]

Although no serious injuries arose from any short-pitched deliveries while a leg theory field was actually set, the tactic led to considerable ill feeling between the two teams, particularly when Australian batsmen suffered injuries, which inflamed spectators.

Short-pitched bowling continues to be permitted in cricket, even when aimed at the batsman. However, over time, several of the Laws of Cricket were changed to render the bodyline tactic less effective.

Definition and origin of the term

Bodyline is a tactic devised for and primarily used in the Ashes series between England and Australia in 1932–33. The tactic involved bowling at leg stump or just outside it, pitching the ball short so that it reared at the body of a batsman standing in an orthodox batting position. A ring of fielders ranged on the leg side would catch any defensive deflection from the bat.[4][5] The batsman's options were to evade the ball through ducking or moving aside, allow the ball to strike his body, or play the ball with his bat. The last course carried additional risks, as defensive shots brought few runs and could carry far enough to be caught by fielders on the leg side, and pull and hook shots could be caught on the edge of the field where two men were usually placed for such a shot.[6][7][8]

Bodyline bowling is intimidatory,[4] and was largely designed as an attempt to curb the prolific scoring of Donald Bradman,[9] although other prolific Australian batsmen such as Bill Woodfull, Bill Ponsford, and Alan Kippax were also targeted.[10]

Several terms were used to describe this style of bowling before the name 'bodyline' was used. Among the first to use it was the writer and former Australian Test cricketer Jack Worrall in the match between the English team and an Australian XI. When 'bodyline' was first used in full, he referred to "half-pitched slingers on the body line" and first used it in print after the first Test. Other writers used a similar phrase around this time, but the first use of 'bodyline' in print seems to have been by the journalist Hugh Buggy in the Melbourne Herald, in his report on the first day's play of the first Test.[11]

Genesis

Leg theory bowling

In the 19th century, most cricketers considered it unsportsmanlike to bowl the ball at the leg stump or for batsmen to hit on the leg side. But by the early years of the 20th century, some bowlers, usually slow or medium-paced, used leg theory as a tactic; the ball was aimed outside the line of leg stump and the fielders placed on that side of the field, the object being to test the batsman's patience and force a rash stroke.[12] Two English left-arm bowlers, George Hirst in 1903–04 and Frank Foster in 1911–12, bowled leg theory to packed leg side fields in Test matches in Australia;[13] Warwick Armstrong used it regularly for Australia.[14] In the years immediately before the First World War, several bowlers used leg theory in county cricket.[12]

When cricket resumed after the war, few bowlers maintained the tactic, which was unpopular with spectators owing to its negativity. Fred Root, the Worcestershire bowler, used it regularly and with considerable success in county cricket. Root later defended the use of leg theory—and bodyline—observing that when bowlers bowled outside off stump, the batsmen were able to let the ball pass them without playing a shot.[15]

Some fast bowlers experimented with leg theory prior to 1932, sometimes accompanying the tactic with short-pitched bowling. In 1925, Australian Jack Scott first bowled a form of what would later have been called bodyline in a state match for New South Wales; his captain Herbie Collins disliked it and would not let him use it again. Other Australian captains were less particular, including Vic Richardson, who asked the South Australian bowler Lance Gun to use it in 1925,[16] and later let Scott use it when he moved to South Australia. Scott repeated the tactics against the MCC in 1928–29.[17][18] In 1927, in a Test trial match, "Nobby" Clark bowled short to a leg-trap (a cluster of fielders placed close on the leg side). He was representing England in a side captained by Douglas Jardine.[19] In 1928–29, Harry Alexander bowled fast leg theory at an England team,[20] and Harold Larwood briefly used a similar tactic on that same tour in two Test matches.[18] Freddie Calthorpe, the England captain, criticised Learie Constantine's use of short-pitched bowling to a leg side field in a Test match in 1930;[21] one such ball struck Andy Sandham, but Constantine only reverted to more conventional tactics after a complaint from the England team.[22]

Donald Bradman

The Australian cricket team toured England in 1930. Australia won the five-Test series 2–1,[23] and Donald Bradman scored 974 runs at a batting average of 139.14, an aggregate record that still stands.[24][25] By the time of the next Ashes series of 1932–33, Bradman's average hovered around 100, approximately twice that of all other world-class batsmen.[26][6] The English cricket authorities felt that new tactics would be required to prevent Bradman being even more successful on Australian pitches;[27] some critics believed that Bradman could be dismissed by leg-spin as Walter Robins and Ian Peebles had supposedly caused him problems; two leg-spinners were included in the English touring party of 1932–33.[28]

Gradually, the idea developed that Bradman was vulnerable to pace bowling. In the final Test of the 1930 Ashes series, while he was batting, the pitch became briefly difficult following rain. Bradman was seen to be uncomfortable facing deliveries which bounced higher than usual at a faster pace, being seen to step back out of the line of the ball. Former England player and Surrey captain Percy Fender was one who noticed, and the incident was much discussed by cricketers. Given that Bradman scored 232, it was not initially thought that a way to curb his prodigious scoring had been found.[29][30] When Douglas Jardine later saw film footage of the Oval incident and noticed Bradman's discomfort, according to his daughter he shouted, "I've got it! He's yellow!"[31] The theory of Bradman's vulnerability developed when Fender received correspondence from Australia in 1932, describing how Australian batsmen were increasingly moving across the stumps towards the off side to play the ball on the on side. Fender showed these letters to Jardine when it became clear that he was to captain the English team in Australia during the 1932–33 tour, and he also discussed Bradman's discomfort at the Oval.[30] It was also known in England that Bradman was dismissed for a four-ball duck by fast bowler Eddie Gilbert, and looked very uncomfortable. Bradman had also appeared uncomfortable against the pace of Sandy Bell in his innings of 299 not out at the Adelaide Oval in South Africa's tour of Australia earlier in 1932, when the desperate bowler decided to bowl short to him, and fellow South African Herbie Taylor, according to Jack Fingleton, may have mentioned this to English cricketers in 1932.[32] Fender felt Bradman might be vulnerable to fast, short-pitched deliveries on the line of leg stump.[33][34] Jardine felt that Bradman was afraid to stand his ground against intimidatory bowling, citing instances in 1930 when he shuffled about, contrary to orthodox batting technique.[6][7]

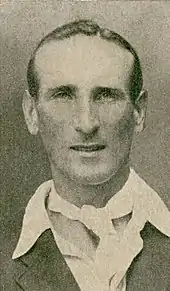

Douglas Jardine

Jardine's first experience against Australia came when he scored an unbeaten 96 to secure a draw against the 1921 Australian touring side for Oxford University. The tourists were criticised in the press for not allowing Jardine to reach his hundred,[35] but had tried to help him with some easy bowling. There has been speculation that this incident helped develop Jardine's antipathy towards Australians, although Jardine's biographer Christopher Douglas denies this.[36] Jardine's attitude towards Australia hardened after he toured the country in 1928–29.[37] When he scored three consecutive hundreds in the early games, he was frequently jeered by the crowd for slow play; the Australian spectators took an increasing dislike to him, mainly for his superior attitude and bearing, his awkward fielding, and particularly his choice of headwear—a Harlequin cap that was given to successful Oxford cricketers.[38] Although Jardine may simply have worn the cap out of superstition, it conveyed a negative impression to the spectators; his general demeanour drew one comment of "Where's the butler to carry the bat for you?"[39] By this stage Jardine had developed an intense dislike for Australian crowds. During his third century at the start of the tour, during a period of abuse from the spectators, he observed to Hunter Hendry that "All Australians are uneducated, and an unruly mob".[38] After the innings, when teammate Patsy Hendren remarked that the Australian crowds did not like Jardine, he replied "It's fucking mutual".[38][40] During the tour, Jardine fielded next to the crowd on the boundary. There, he was roundly abused and mocked for his awkward fielding, particularly when chasing the ball.[41] On one occasion, he spat towards the crowd while fielding on the boundary as he changed position for the final time.[38]

Jardine was appointed captain of England for the 1931 season, replacing Percy Chapman who had led the team in 1930. He defeated New Zealand in his first series, but opinion was divided as to how effective he had been.[42] The following season, he led England again and was appointed to lead the team to tour Australia for the 1932–33 Ashes series.[43] A meeting was arranged between Jardine, Nottinghamshire captain Arthur Carr and his two fast bowlers Harold Larwood and Bill Voce at London's Piccadilly Hotel to discuss a plan to combat Bradman.[44] Jardine asked Larwood and Voce if they could bowl on leg stump and make the ball rise into the body of the batsman. The bowlers agreed they could, and that it might prove effective.[33][45][46] Jardine also visited Frank Foster to discuss his field-placing in Australia in 1911–12.[13]

Larwood and Voce practised the plan over the remainder of the 1932 season with varying but increasing success and several injuries to batsmen.[47][48] Ken Farnes experimented with short-pitched, leg-theory bowling but was not selected for the tour. Bill Bowes also used short-pitched bowling, notably against Jack Hobbs.[49]

Ashes series of 1932–33

Early development on tour

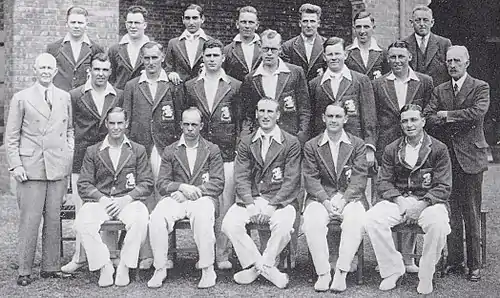

The England team which toured Australia in 1932–33 contained four fast bowlers and a few medium pacers; such a heavy concentration on pace was unusual at the time, and drew comment from the Australian press and players, including Bradman.[50] On the journey, Jardine instructed his team on how to approach the tour and discussed tactics with several players, including Larwood;[51] at this stage, he seems to have settled on leg theory, if not full bodyline, as his main tactic.[52] Some players later reported that he told them to hate the Australians in order to defeat them, while instructing them to refer to Bradman as "the little bastard."[51] Upon arrival, Jardine quickly alienated the press and crowds through his manner and approach.[53][54]

In the early matches, although there were instances of the English bowlers pitching the ball short and causing problems with their pace, full bodyline tactics were not used.[55] There had been little unusual about the English bowling except the number of fast bowlers. Larwood and Voce were given a light workload in the early matches by Jardine.[54] The English tactics changed in a game against an Australian XI team at Melbourne in mid-November, when full bodyline tactics were deployed for the first time.[56][57] Jardine had left himself out of the English side, which was led instead by Bob Wyatt who later wrote that the team experimented with a diluted form of bodyline bowling. He reported to Jardine that Bradman, who was playing for the opposition, seemed uncomfortable against the bowling tactics of Larwood, Voce and Bowes. The crowd, press and Australian players were shocked by what they experienced and believed that the bowlers were targeting the batsmen's heads. Bradman adopted unorthodox tactics—ducking, weaving and moving around the crease—which did not meet with universal approval from Australians and he scored just 36 and 13 in the match.[58]

The tactic continued to be used in the next game by Voce (Larwood and Bowes did not play in this game), against New South Wales, for whom Jack Fingleton made a century and received several blows in the process. Bradman again failed twice, and had scored just 103 runs in six innings against the touring team; many Australian fans were now worried by Bradman's form.[59] Meanwhile, Jardine wrote to tell Fender that his information about the Australian batting technique was correct and that it meant he was having to move more and more fielders onto the leg side: "if this goes on I shall have to move the whole bloody lot to the leg side."[60][61]

The Australian press were shocked and criticised the hostility of Larwood in particular.[62] Some former Australian players joined the criticism, saying the tactics were ethically wrong. But at this stage, not everyone was opposed,[63] and the Australian Board of Control believed the English team had bowled fairly.[64] On the other hand, Jardine increasingly came into disagreement with tour manager Warner over bodyline as the tour progressed.[65] Warner hated bodyline but would not speak out against it. He was accused of hypocrisy for not taking a stand on either side,[66] particularly after expressing sentiments at the start of the tour that cricket "has become a synonym for all that is true and honest. To say 'that is not cricket' implies something underhand, something not in keeping with the best ideals ... all who love it as players, as officials or spectators must be careful lest anything they do should do it harm."[67]

First two Test matches

Bradman missed the first Test at Sydney, worn out by constant cricket and the ongoing argument with the Board of Control.[68] Jardine later wrote that the real reason was that the batsman had suffered a nervous breakdown.[56][69] The English bowlers used bodyline intermittently in the first match, to the crowd's vocal displeasure,[70] and the Australians lost the game by ten wickets.[notes 1] Larwood was particularly successful, returning match figures of ten wickets for 124 runs.[71] One of the English bowlers, Gubby Allen, refused to bowl with fielders on the leg side, clashing with Jardine over these tactics.[72][notes 2] The only Australian batsman to make an impact was Stan McCabe, who hooked and pulled everything aimed at his upper body,[74] to score 187 not out in four hours from 233 deliveries.[71][56] Behind the scenes, administrators began to express concerns to each other. Yet the English tactics still did not earn universal disapproval; former Australian captain Monty Noble praised the English bowling.[75]

Meanwhile, Woodfull was being encouraged to retaliate to the short-pitched English attack, not least by members of his own side such as Vic Richardson, or to include pace bowlers such as Eddie Gilbert or Laurie Nash to match the aggression of the opposition.[76] But Woodfull refused to consider doing so.[77][78][79] He had to wait until minutes before the game before he was confirmed as captain by the selectors.[80][81]

For the second Test, Bradman returned to the team after his newspaper employers released him from his contract.[82] England continued to use bodyline and Bradman was dismissed by his first ball in the first innings.[notes 3] In the second innings, against the full bodyline attack, he scored an unbeaten century which helped Australia to win the match and level the series at one match each.[85] Critics began to believe bodyline was not quite the threat that had been perceived and Bradman's reputation, which had suffered slightly with his earlier failures, was restored. However, the pitch was slightly slower than others in the series, and Larwood was suffering from problems with his boots which reduced his effectiveness.[86][87]

Third Test match

The controversy reached its peak during the Third Test at Adelaide. On the second day, a Saturday, before a crowd of 50,962 spectators,[81][88] Australia bowled out England who had batted through the first day. In the third over of the Australian innings, Larwood bowled to Woodfull. The fifth ball narrowly missed Woodfull's head and the final ball, delivered short on the line of middle stump, struck Woodfull over the heart. The batsman dropped his bat and staggered away holding his chest, bent over in pain. The England players surrounded Woodfull to offer sympathy but the crowd began to protest noisily. Jardine called to Larwood: "Well bowled, Harold!" Although the comment was aimed at unnerving Bradman, who was also batting at the time, Woodfull was appalled.[89][90] Play resumed after a brief delay, once it was certain the Australian captain was fit to carry on and, since Larwood's over had ended, Woodfull did not have to face the bowling of Allen in the next over. However, when Larwood was ready to bowl at Woodfull again, play was halted once more when the fielders were moved into bodyline positions, causing the crowd to protest and call abuse at the England team. Subsequently, Jardine claimed that Larwood requested a field change, Larwood said that Jardine had done so.[91] Many commentators condemned the alteration of the field as unsporting, and the angry spectators became extremely volatile.[92] Jardine, although writing that Woodfull could have retired hurt if he was unfit, later expressed his regret at making the field change at that moment.[91] The fury of the crowd was such that a riot might have occurred had another incident taken place and several writers suggested that the anger of the spectators was the culmination of feelings built up over the two months that bodyline had developed.[92]

During the over, another rising Larwood delivery knocked the bat out of Woodfull's hands. He batted for 89 minutes, being hit a few more times before Allen bowled him for 22.[93] Later in the day, Pelham Warner, one of the England managers, visited the Australian dressing room. He expressed sympathy to Woodfull but was surprised by the Australian's response. According to Warner, Woodfull replied, "I don't want to see you, Mr Warner. There are two teams out there. One is trying to play cricket and the other is not."[94] Fingleton wrote that Woodfull had added, "This game is too good to be spoilt. It is time some people got out of it."[95] Woodfull was usually dignified and quietly spoken, making his reaction surprising to Warner and others present.[94][96] Warner was so shaken that he was found in tears later that day in his hotel room.[97]

There was no play on the following day, Sunday being a rest day, but on Monday morning, the exchange between Warner and Woodfull was reported in several Australian newspapers.[98] The players and officials were horrified that a sensitive private exchange had been reported to the press. Leaks to the press were practically unknown in 1933. David Frith notes that discretion and respect were highly prized and such a leak was "regarded as a moral offence of the first order."[99] Woodfull made it clear that he severely disapproved of the leak, and later wrote that he "always expected cricketers to do the right thing by their team-mates."[100][101] As the only full-time journalist in the Australian team, suspicion immediately fell on Fingleton, although as soon as the story was published, he told Woodfull he was not responsible. Warner offered Larwood a reward of one pound if he could dismiss Fingleton in the second innings; Larwood obliged by bowling him for a duck.[100][102] Fingleton later claimed that Sydney Sun reporter Claude Corbett had received the information from Bradman;[103] for the rest of their lives, Fingleton and Bradman made claim and counter-claim that the other man was responsible for the leak.[104]

The following day, as Australia faced a large deficit on the first innings, Bert Oldfield played a long innings in support of Bill Ponsford, who scored 85. In the course of the innings, the English bowlers used bodyline against him, and he faced several short-pitched deliveries but took several fours from Larwood to move to 41.[105] Having just conceded a four, Larwood bowled fractionally shorter and slightly slower. Oldfield attempted to hook but lost sight of the ball and edged it onto his temple; the ball fractured his skull. Oldfield staggered away and fell to his knees and play stopped as Woodfull came onto the pitch and the angry crowd jeered and shouted, once more reaching the point where a riot seemed likely. Several English players thought about arming themselves with stumps should the crowd come onto the field.[106] The ball which injured Oldfield was bowled to a conventional, non-bodyline field;[107] Larwood immediately apologised but Oldfield said that it was his own fault before he was helped back to the dressing room and play continued.[106][notes 4] Jardine later secretly sent a telegram of sympathy to Oldfield's wife and arranged for presents to be given to his young daughters.[109]

The cable exchange

At the end of the fourth day's play of the third Test match, the Australian Board of Control sent a cable to the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), cricket's ruling body and the club that selected the England team, in London:

Australian Board of Control to MCC, January 18, 1933:

Bodyline bowling assumed such proportions as to menace best interests of game, making protection of body by batsmen the main consideration. Causing intensely bitter feeling between players, as well as injury. In our opinion is unsportsmanlike. Unless stopped at once likely to upset friendly relations between Australia and England.[110]

Not all Australians, including the press and players, believed that the cable should have been sent, particularly immediately following a heavy defeat.[111] The suggestion of unsportsmanlike behaviour was deeply resented by the MCC, and was one of the worst accusations that could have been levelled at the team at the time. Additionally, members of the MCC believed that the Australians had over-reacted to the English bowling.[5][112] The MCC took some time to draft a reply:

MCC to Australian Board of Control, January 23, 1933:

We, Marylebone Cricket Club, deplore your cable. We deprecate your opinion that there has been unsportsmanlike play. We have fullest confidence in captain, team and managers, and are convinced they would do nothing to infringe either the Laws of Cricket or the spirit of the game. We have no evidence that our confidence is misplaced. Much as we regret accidents to Woodfull and Oldfield, we understand that in neither case was the bowler to blame. If the Australian Board of Control wish to propose a new law or rule it shall receive our careful consideration in due course. We hope the situation is not now as serious as your cable would seem to indicate, but if it is such as to jeopardise the good relations between English and Australian cricketers, and you would consider it desirable to cancel remainder of programme, we would consent with great reluctance.[113]

At this point, the remainder of the series was under threat.[114][115] Jardine was shaken by the events and by the hostile reactions to his team. Stories appeared in the press, possibly leaked by the disenchanted Nawab of Pataudi,[116] about fights and arguments between the England players. Jardine offered to stop using bodyline if the team did not support him, but after a private meeting (not attended by Jardine or either of the team managers) the players released a statement fully supporting the captain and his tactics.[117][118] Even so, Jardine would not have played in the fourth Test without the withdrawal of the unsportsmanlike accusation.[119]

The Australian Board met to draft a reply cable, which was sent on 30 January, indicating that they wished the series to continue and offering to postpone consideration of the fairness of bodyline bowling until after the series. The MCC's reply, on 2 February, suggested that continuing the series would be impossible unless the accusation of unsporting behaviour was withdrawn.[120]

The situation escalated into a diplomatic incident. Figures high up in both the British and Australian government saw bodyline as potentially fracturing an international relationship that needed to remain strong.[121] The Governor of South Australia, Alexander Hore-Ruthven, who was in England at the time, expressed his concern to British Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs James Henry Thomas that this would cause a significant impact on trade between the nations.[122][3] The standoff was settled when the Australian prime minister, Joseph Lyons, met with members of the Australian Board and outlined to them the severe economic hardships that could be caused in Australia if the British public boycotted Australian trade. Following considerable discussion and debate in the English and Australian press, the Australian Board sent a cable to the MCC which, while maintaining its opposition to bodyline bowling, stated "We do not regard the sportsmanship of your team as being in question".[3][123] Even so, correspondence between the Australian Board and the MCC continued for almost a year.[124]

The end of the series

Voce missed the fourth Test of the series, being replaced by a leg spinner, Tommy Mitchell. Larwood continued to use bodyline, but he was the only bowler in the team using the tactic; even so, he used it less frequently than usual and seemed less effective in high temperatures and humidity.[125] England won the game by eight wickets, thanks in part to an innings of 83 by Eddie Paynter who had been admitted to hospital with tonsillitis but left in order to bat when England were struggling in their innings.[126][127] Voce returned for the final Test, but neither he nor Allen were fully fit,[128] and despite the use of bodyline tactics, Australia scored 435 at a rapid pace, aided by several dropped catches.[129] Australia included a fast bowler for this final game, Harry Alexander who bowled some short deliveries but was not allowed to use many fielders on the leg side by his captain, Woodfull.[130] England built a lead of 19 but their tactics in Australia's second innings were disrupted when Larwood left the field with an injured foot; Hedley Verity, a spinner, claimed five wickets to bowl Australia out;[131] England won by eight wickets and won the series by four Tests to one.[132]

In England

Bodyline continued to be bowled occasionally in the 1933 English season—most notably by Nottinghamshire, who had Carr, Voce and Larwood in their team.[133] This gave the English crowds their first chance to see what all the fuss was about. Ken Farnes, the Cambridge University fast bowler, also bowled it in the University Match, hitting a few Oxford batsmen.

Jardine himself had to face bodyline bowling in a Test match. The West Indian cricket team toured England in 1933, and, in the second Test at Old Trafford, Jackie Grant, their captain, decided to try bodyline. He had a couple of fast bowlers, Manny Martindale and Learie Constantine.[133] Facing bodyline tactics for the first time, England first suffered, falling to 134 for 4,[134] with Wally Hammond being hit on the chin,[133] though he recovered to continue his innings. Then Jardine himself faced Martindale and Constantine.[133] Jardine never flinched. With Les Ames finding himself in difficulties, Jardine said, "You get yourself down this end, Les. I'll take care of this bloody nonsense."[135] He played right back to the bouncers, standing on tiptoe, and played them with a dead bat, sometimes playing the ball one handed for more control.[135] While the Old Trafford pitch was not as suited to bodyline as the hard Australian wickets, Martindale did take 5 for 73, but Constantine only took 1 for 55.[134] Jardine himself made 127, his only Test century.[133] In the West Indian second innings, Clark bowled bodyline back to the West Indians, taking 2 for 64. The match in the end was drawn but played a large part in turning English opinion against bodyline. The Times used the word bodyline, without using inverted commas or using the qualification so-called, for the first time.[136] Wisden also said that "most of those watching it for the first time must have come to the conclusion that, while strictly within the law, it was not nice."[136][137]

In 1934, Bill Woodfull led Australia back to England on a tour that had been under a cloud after the tempestuous cricket diplomacy of the previous bodyline series. Jardine had retired from International cricket in early 1934 after captaining a fraught tour of India and under England's new captain, Bob Wyatt, agreements were put in place so that bodyline would not be used.[138][139][140] However, there were occasions when the Australians felt that their hosts had crossed the mark with tactics resembling bodyline.[138]

In a match between the Australians and Nottinghamshire, Voce, one of the bodyline practitioners of 1932–33, employed the strategy with the wicket-keeper standing to the leg side and took 8/66.[140][141] In the second innings, Voce repeated the tactic late in the day, in fading light against Woodfull and Bill Brown. Of his 12 balls, 11 were no lower than head height.[141] Woodfull told the Nottinghamshire administrators that, if Voce's leg-side bowling was repeated, his men would leave the field and return to London. He further said that Australia would not return to the country in the future. The following day, Voce was absent, ostensibly due to a leg injury.[140][141][142][143] Already angered by the absence of Larwood, the Nottinghamshire faithful heckled the Australians all day.[140] Australia had previously and privately complained that some pacemen had strayed past the agreement in the Tests.[141]

Changes to the laws of cricket

As a direct consequence of the 1932–33 tour,[112] the MCC introduced a new rule to the laws of cricket for the 1935 English cricket season.[144] Originally, the MCC hoped that captains would ensure that the game was played in the correct spirit, and passed a resolution that bodyline bowling would breach this spirit.[112][145] When this proved to be insufficient,[112] the MCC passed a law that "direct attack" bowling was unfair and became the responsibility of the umpires to identify and stop.[144] In 1957, the laws were altered to prevent more than two fielders standing behind square on the leg side; the intention was to prevent negative bowling tactics whereby off spinners and slow inswing bowlers aimed at the leg stump of batsmen with fielders concentrated on the leg side.[146] However, an indirect effect was to make bodyline fields impossible to implement.[112]

Later law changes, under the heading of "Intimidatory Short Pitched Bowling", also restricted the number of "bouncers" which might be bowled in an over. Nevertheless, the tactic of intimidating the batsman is still used to an extent that would have been shocking in 1933, although it is less dangerous now because today's players wear helmets and generally far more protective gear.[147][148] The West Indies teams of the 1980s, who regularly fielded a bowling attack comprising some of the best fast bowlers in cricket history, were perhaps the most feared exponents.[149]

Reaction

The English players and management were consistent in referring to their tactic as fast leg theory considering it to be a variant of the established and unobjectionable leg theory tactic. The inflammatory term "bodyline" was coined and perpetuated by the Australian press (see below). English writers used the term fast leg theory. The terminology reflected differences in understanding, as neither the English public nor the Board of the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC)—the governing body of English cricket—could understand why the Australians were complaining about what they perceived as a commonly used tactic. Some concluded that the Australian cricket authorities and public were sore losers.[150][151] Of the four fast bowlers in the tour party, Gubby Allen was a voice of dissent in the English camp, refusing to bowl short on the leg side,[147] and writing several letters home to England critical of Jardine, although he did not express this in public in Australia.[72] A number of other players, while maintaining a united front in public, also deplored bodyline in private. The amateurs Bob Wyatt (the vice-captain), Freddie Brown and the Nawab of Pataudi opposed it,[147] as did Wally Hammond and Les Ames among the professionals.[152]

During the season, Woodfull's physical courage, stoic and dignified leadership won him many admirers. He flatly refused to employ retaliatory tactics and did not publicly complain even though he and his men were repeatedly hit.[8][153]

Jardine however insisted his tactic was not designed to cause injury and that he was leading his team in a sportsmanlike and gentlemanly manner, arguing that it was up to the Australian batsmen to play their way out of trouble.[109]

It was subsequently revealed that several of the players had private reservations, but they did not express them publicly at the time.[117][118]

Legacy

Following the 1932–33 series, several authors, including many of the players involved, released books expressing various points of view about bodyline. Many argued that it was a scourge on cricket and must be stamped out, while some did not see what all the fuss was about.[154] The series has been described as the most controversial period in Australian cricket history,[8] and voted the most important Australian moment by a panel of Australian cricket identities.[155] The MCC asked Harold Larwood to sign an apology to them for his bowling in Australia, making his selection for England again conditional upon it. Larwood was furious at the notion, pointing out that he had been following orders from his captain, and that was where any blame should lie.[156] Larwood refused, never played for England again,[133] and became vilified in his own country.[157] Douglas Jardine always defended his tactics and in the book he wrote about the tour, In Quest of the Ashes, described allegations that the England bowlers directed their attack with the intention of causing physical harm as stupid and patently untruthful.[158] The immediate effect of the law change which banned bodyline in 1935 was to make commentators and spectators sensitive to the use of short-pitched bowling; bouncers became exceedingly rare and bowlers who delivered them were practically ostracised.[159] This attitude ended after the Second World War, and among the first teams to make extensive use of short-pitched bowling was the Australian team captained by Bradman between 1946 and 1948. Other teams soon followed.[160]

Outside the sport, there were significant consequences for Anglo-Australian relations, which remained strained until the outbreak of World War II made cooperation paramount. Business between the two countries was adversely affected as citizens of each country avoided goods manufactured in the other. Australian commerce also suffered in British colonies in Asia: the North China Daily News published a pro-bodyline editorial, denouncing Australians as sore losers. An Australian journalist reported that several business deals in Hong Kong and Shanghai were lost by Australians because of local reactions.[161] English immigrants in Australia found themselves shunned and persecuted by locals, and Australian visitors to England were treated similarly.[162] In 1934–35 a statue of Prince Albert in Sydney was vandalised, with an ear being knocked off and the word "BODYLINE" painted on it.[163] Both before and after World War II, numerous satirical cartoons and comedy skits were written, mostly in Australia, based on events of the bodyline tour. Generally, they poked fun at the English.[164]

In 1984, Australia's Network Ten produced a television mini-series titled Bodyline, dramatising the events of the 1932–33 English tour of Australia. It starred Gary Sweet as Don Bradman, Hugo Weaving as Douglas Jardine, Jim Holt as Harold Larwood, Rhys McConnochie as Pelham Warner, and Frank Thring as Jardine's mentor Lord Harris.[165] The series took some liberties with historical accuracy for the sake of drama, including a depiction of angry Australian fans burning a British flag at the Sydney Cricket Ground, an event which was never documented.[165] Larwood, having emigrated to Australia in 1950, was largely welcomed with open arms, although received several threatening and obscene phone calls after the series aired.[166] The series was widely and strongly attacked by the surviving players for its inaccuracy and sensationalism.[166]

To this day, the bodyline tour remains one of the most significant events in the history of cricket, and strong in the consciousness of many cricket followers. In a poll of cricket journalists, commentators, and players in 2004, the bodyline tour was ranked the most important event in cricket history.[167]

Notes and references

Notes

- Winning by ten wickets means that the team batting last had ten wickets left to fall when they passed their opponent's match aggregate of runs.

- Allen, whose definition of bodyline differed from that of others, maintained that England did not use bodyline until the second innings of the second Test, when Larwood began to bowl outside leg stump.[73] Despite his objection to bodyline, he fielded in the leg trap throughout the series and took several catches off Larwood's bowling.[72]

- Jardine, who was known for being extremely dour even by the standards of the day,[83] was seen to be so delighted that he had clasped his hands above his head and performed a "war dance".[84]

- As a result of the injuries in this game, the costs of insurance cover for players doubled.[108]

References

- Unit 2 – Managing the Match: Management issues and umpiring Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. International Institute of Cricket Umpiring and Scoring. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Frith, pp. 241–59.

- Pollard, pp. 260–261.

- Douglas, p. 103.

- Watson, Greig (16 January 2013). "Bodyline: 80 years of cricket's greatest controversy". BBC. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- Piesse, p. 130.

- Haigh and Frith, p. 70.

- Colman, p. 171.

- Douglas, pp. 86, 111.

- Frith, p. 44.

- Frith, pp. 35–36.

- Frith, pp. 22–23.

- Frith, pp. 18–19.

- Frith, p. 25.

- Frith, p. 23.

- Frith, pp. 27–29.

- Douglas, pp. 79–80.

- Frith, pp. 28–29.

- Douglas, pp. 59–60.

- Douglas, p. 83.

- Howat (1976), p. 60.

- Frith, pp. 31–32.

- "Statsguru—Australia—Tests—Results list". Cricinfo. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- "Records: Test matches: Batting records: Most runs in a series". ESPNcricinfo. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- Perry, p. 133.

- Cashman, pp. 32–35.

- Frith, pp. 39–41.

- Douglas, p. 121.

- Frith, pp. 42–43.

- Douglas, p. 111.

- Frith, p. 50

- Frith, pp. 39–40; p. 48

- Perry, p. 135.

- Pollard, p. 244.

- Fingleton (1981), pp. 81–82.

- Douglas, pp. 30–31.

- Douglas, p. 64.

- Frith, p. 71.

- Fingleton (1981), pp. 84–85.

- Douglas, p. 68.

- Douglas, p. 82.

- Douglas, pp. 93–95.

- Douglas, pp. 107–08.

- Perry, p. 134.

- Frith, pp. 43–44.

- Pollard, p. 242.

- Frith, pp. 45–48.

- Douglas, pp. 113–117.

- Frith, pp. 49–50.

- Frith, pp. 54–55.

- Frith, pp. 61, 66.

- Douglas, pp. 123–24.

- Frith, pp. 69, 90–91.

- Douglas, p. 126.

- Frith, pp. 79–94.

- Harte, p. 344.

- Pollard, p. 249.

- Frith, pp. 94–96.

- Frith, pp. 99–105.

- Frith, p. 105.

- Douglas, p. 128.

- Frith, pp. 97–98.

- Frith, pp. 106–7.

- Frith, p. 99.

- Frith, p. 98.

- Growden, pp. 62–63.

- Frith, p. 68.

- Frith, p. 109.

- Haigh and Frith, p. 71.

- Frith, pp. 117, 120, 126, 134.

- Frith, p. 137.

- Frith, p. 116.

- Swanton, pp. 137–38.

- Colman, p. 172.

- Frith, pp. 134–35.

- Whitington and Hele, p. 132.

- Frith, p. 134.

- Haigh, Gideon (22 October 2007). "Gideon Haigh on Bodyline: A tactic of its time". ESPNCricinfo. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- Colman, pp. 181–182.

- O'Reilly, p.88.

- Harte, p. 346.

- Frith, p. 139.

- Piesse, p. 132.

- Bowes, p. 107.

- Frith, pp. 150, 159–63.

- Douglas, p. 137.

- Frith, p. 165.

- Haigh and Frith, p. 73.

- Hamilton, p. 156.

- Frith, p. 179.

- Frith, p. 180.

- Frith, p. 181.

- Frith, p. 182.

- Frith, p. 185.

- Fingleton (1947), p. 18.

- Fingleton (1947), p. 17.

- Hamilton, pp. 156–57.

- Frith, p. 194.

- Frith, p. 187.

- Frith, p. 188.

- Growden, p. 72.

- Hamilton, p. 157.

- Fingleton (1981), p. 108.

- Frith, pp. 187–92.

- Frith, pp. 194–96.

- Frith, pp. 196–98.

- Frith, p. 200.

- Frith and Haigh, p. 77.

- Frith, p. 201.

- Frith, p. 218.

- Frith, pp. 218–19.

- Williamson, Martin. "A brief history ... Bodyline". ESPNCricinfo. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- Frith, pp. 218–22.

- Pollard, p. 259.

- Frith, p. 227.

- Frith, p. 215.

- Frith, pp. 214–15.

- Douglas, p. 146.

- Douglas, pp. 145–46.

- Frith, pp. 226–28.

- Frith, pp. 241–59.

- Frith, pp. 242–248.

- Frith, pp. 255–259.

- Douglas, pp. 145–47.

- Frith, pp. 274, 277, 293.

- Frith, pp. 288–91.

- "England v Australia 1932–33 (Fourth Test)". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1934. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- Frith, p. 309

- Frith, p. 314.

- Frith, pp. 315–18.

- Frith, pp. 324–25.

- Frith, pp. 328, 330.

- Perry, p. 141.

- "HowSTAT! Match Scorecard". Howstat.com.au. 22 July 1933. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- Douglas, p.166.

- Douglas, p.168.

- See Cricinfo for the scorecard of the second Test between England and West Indies in 1933.

- Haigh and Frith, p. 84.

- Harte, p. 354.

- Robinson, p. 164.

- Haigh and Frith, p. 85.

- Perry, pp. 147–148.

- Harte, p. 356.

- Frith, p. 408.

- Frith, p. 374.

- Chalke, Stephen; Hodgson, Derek (2003). No Coward Soul. The remarkable story of Bob Appleyard. Bath: Fairfield Books. p. 177. ISBN 0-9531196-9-6.

- "A Dummy's Guide to Bodyline". Cricinfo. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- Frith, pp. 10–17.

- Dellor, Ralph. "Cricinfo Player Profile, Clive Lloyd". Cricinfo. Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- Frith, pp. 142, 222, 231–238.

- Pollard, p. 258.

- E. W. Swanton. Sort of a Cricket Person, William Collins & Sons, 1972, p. 19.

- Cashman, pp. 322–323.

- Frith, pp. 378–397.

- Haigh and Frith, foreword.

- Frith, pp. 399–401.

- Frith, pp. 437–441.

- Douglas, p. 157.

- Frith, pp. 410–17.

- Frith, pp. 418–20.

- Frith, p. 382.

- Frith, p. 383.

- Frith, p. 384.

- Frith, pp. 381, 385.

- Frith, p. 386.

- Frith, p. 387.

- "It just wasn't cricket". The Sun-Herald. 8 February 2004. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

References

- Bowes, Bill (1949). Express Deliveries. London: Stanley Paul. OCLC 643924774.

- Cashman, Richard; Franks, Warwick; Maxwell, Jim; Sainsbury, Erica; Stoddart, Brian; Weaver, Amanda; Webster, Ray (1997). The A–Z of Australian cricketers. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-9756746-1-7.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Colman, Mike; Edwards, Ken (2002). Eddie Gilbert:The true story of an Aboriginal cricketing legend. Sydney, New South Wales: ABC Books. ISBN 0-7333-1154-7.

- Douglas, Christopher (2002). Douglas Jardine: Spartan Cricketer. Methuen. ISBN 0-413-77216-0.

- Fingleton, Jack (1947). Cricket Crisis. London, Melbourne: Cassell.

- Fingleton, Jack (1981). Batting from Memory. Collins. ISBN 0-00-216359-4.

- Frith, David (2002). Bodyline Autopsy. Sydney, New South Wales: ABC Books. ISBN 0-7333-1321-3.

- Gibson, Alan (1989). The Cricket Captains of England. The Pavilion Library. ISBN 1-85145-390-3.

- Growden, Greg (2008). Jack Fingleton : the man who stood up to Bradman. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-548-0.

- Haigh, Gideon; Frith, David (2007). Inside story: unlocking Australian cricket's archives. Southbank, Victoria: News Custom Publishing. ISBN 1-921116-00-5.

- Hamilton, Duncan (2009). Harold Larwood. London: Quercus. ISBN 978-1-84916-207-4.

- Harte, Chris; Whimpress, Bernard (2003). The Penguin History of Australian Cricket. Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin Books Australia. ISBN 0-670-04133-5.

- Howat, Gerald (1976). Learie Constantine. Newton Abbot: Readers Union Limited. (Book Club edition. First published London, 1975. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-920043-7)

- Jardine, Douglas (1933). In Quest of the Ashes. Hutchison.

- Le Quesne, Laurence (1983). The bodyline controversy. Martin Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0-436-24410-1.

- O'Reilly, Bill (1985). Tiger—60 Years of Cricket. Collins. ISBN 0-00-217477-4.

- Perry, Roland (2006). The Ashes: a celebration. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House Australia. ISBN 1-74166-490-X.

- Piesse, Ken (2003). Cricket's Colosseum: 125 Years of Test Cricket at the MCG. South Yarra, Victoria: Hardie Grant Books. ISBN 1-74066-064-1.

- Pollard, Jack (1988). The Bradman Years: Australian Cricket 1918–48. North Ryde, New South Wales: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-207-15596-8.

- Robinson, Ray (1975). On top down under : Australia's cricket captains. Stanmore, New South Wales: Cassell Australia. ISBN 0-7269-7364-5.

- Wheeler, Paul (1983). Bodyline: The Novel. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-13383-5.

- Bodyline IMDB entry.. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- Whitington, Richard; Hele, George (1974). Bodyline Umpire. Adelaide, South Australia: Rigby. ISBN 0-85179-820-9.

External links

- Footage of the 1933 Ashes test where bodyline bowling is used on Don Bradman

- The Bodyline Series Original reports from The Times

- Bodyline Series – State Library of NSW