Laurie Nash

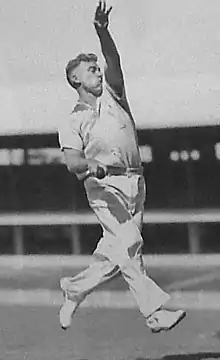

Laurence John "Laurie" Nash (2 May 1910 – 24 July 1986) was a Test cricketer and Australian rules footballer. An inductee into the Australian Football Hall of Fame, Nash was a member of South Melbourne's 1933 premiership team, captained South Melbourne in 1937 and was the team's leading goal kicker in 1937 and 1945. In cricket, Nash was a fast bowler and hard hitting lower order batsman who played two Test matches for Australia, taking 10 wickets at 12.80 runs per wicket, and scoring 30 runs at a batting average of 15.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Laurence John Nash | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 2 May 1910 Fitzroy, Victoria, Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 24 July 1986 (aged 76) Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 5 ft 9 in (1.75 m) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right-arm fast | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | All-rounder | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut (cap 143) | 12 February 1932 v South Africa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 3 March 1937 v England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1929–1932 | Tasmania | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1933–1937 | Victoria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: CricketArchive, 20 January 2009 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The son of a leading Australian rules footballer of the early twentieth century who had also played cricket against the touring Marylebone Cricket Club in 1921, Nash was a star sportsman as a boy. Following the family's relocation from Victoria to Tasmania, he began to make a name for himself as both a footballer and a cricketer, and became both one of the earliest professional club cricketers in Australia and one of the first fully professional Australian rules footballers. Nash made his Test cricket debut in 1932, against South Africa and his Victorian Football League (VFL) debut in 1933.

While Nash had great success in football, he faced opposition from the cricket establishment for his supposedly poor attitude towards authority. This led fellow cricketer Keith Miller to write that his non-selection as a regular Test player was "the greatest waste of talent in Australian cricket history".[1]

During World War II Nash rejected offers of a home posting and instead served as a trooper in New Guinea, stating that he wished to be treated no differently from any other soldier. Following the end of the war, Nash returned to South Melbourne and won the team goal kicking award, although his age and injuries inhibited any return of his previous successes. Nash retired from VFL football at the end of the 1945 season to play and coach in the country before returning to coach South Melbourne in 1953. After retiring, Nash wrote columns for newspapers, was a panellist on football television shows and was a publican before his death in Melbourne, aged 76.

Early life

Nash was born in Fitzroy, Victoria on 2 May 1910, the youngest of three children of Irish Catholics Robert and Mary Nash.[2] He had a brother, Robert Junior, and one sister, Mary, known as Maizie.[3]

Nash belonged to a sporting family; his grandfather Michael Nash and great-uncle Thomas Nash were leading players for Carlton Football Club in the 1880s,[4] his father Robert captained Collingwood Football Club and coached Footscray Football Club,[5] and played cricket, opening the bowling for Hamilton in a match against the 1920–1921 touring English side,[6] while Robert Junior also became a leading footballer in Tasmania and country Victoria. Nash's mother was an orphan who was probably adopted several times, allowing historians no opportunity to determine any sporting links on her side of the family.[7] Nash's biographer also claims that former Prime Minister of New Zealand Sir Walter Nash and pianist Eileen Joyce were related to the family.[8]

Nash's father, who had initially worked as a gas stoker, joined the police force in 1913[2] and served in a number of postings, including Hamilton in western Victoria, taking his family with him.[9] In Hamilton, Nash attended Loreto Convent and began his interest in sport, practising kicking a football made of newspapers and tied together with string.[10]

When Nash Senior was transferred back to Melbourne in 1922, the Nash brothers attended St Ignatius School in the Melbourne working-class suburb of Richmond, where Nash became best friends with fellow student Tommy Lahiff, who would also become a leading Australian rules footballer.[9]

Although short and stocky, Nash and his brother Robert Junior developed into star junior sportsmen,[5] excelling at football and cricket, although Nash Senior preferred Laurie to become a cricketer, considering it a better and longer career option[11] and forbade his sons from playing senior football until age 20.[12]

Nash's performance in junior cricket led Victorian district cricket club Fitzroy to sign him for the 1927/28 season.[5] Nash made his first grade debut for Fitzroy as a seventeen-year-old and spent two and a half seasons at Fitzroy, earning plaudits for his performances and, until he broke his wrist in a fielding mishap,[13] there were suggestions that he was close to Victorian selection.[14]

Nash Senior was a member of a group of 600 police who went on strike in 1923 for better wages but was dismissed from the force[12] and required to find another livelihood. Nash Senior went into the hotel business, firstly in Melbourne before eventually moving his family to Tasmania in 1929 to run the hotel at Parattah.[12]

Tasmania

In Tasmania, Nash gained work in a Launceston sport store[11] and made his Tasmanian district cricket debut for the Tamar Cricket Club on 7 December 1929, taking 7 wickets for 29 (7/29) and 1/16.[15] After one more match for Tamar, in which he took 5/41, Nash was chosen in the Northern Tasmania side in the annual match against Southern Tasmania, where he took match figures of 7/40 and top scored in both innings.[15]

These performances led Nash to make his first-class cricket debut for Tasmania against Victoria in Launceston on 31 December 1929, taking 2/97, with future Test player Leo O'Brien his maiden first-class wicket, and scoring 1 and 48 (Tasmania's top score in their second innings).[16]

Four months later, he made his senior football debut for the Roy Cazaly coached City side in the Northern Tasmanian Football Association (NTFA),[17] immediately standing out on account of his skills, blond hair and confidence in his abilities. Nash made the Tasmanian side for the national carnival in Adelaide where he won the medal for the most outstanding Tasmanian player of the carnival.[18] Nash played in defence for City while Robert Junior played in the forward line and both were considered sensational.[19]

Between 1930 and 1932 Nash played 45 games for City (including premierships in 1930 and 1932), kicking 14 goals, and winning the Tasman Shields Trophy, awarded to the Best and Fairest player in the NTFA, in 1931 and 1932.[18] Additionally, Nash played 10 games for Northern Tasmania (12 goals) and 5 games for Tasmania at the national carnival.[20]

Nash played for Tasmania against the touring West Indian cricket team in December 1930. Batting at number three, Nash made 41 and 0 and took 2/87, including bowling Learie Constantine,[21] who had scored 100 in 65 minutes.[22] Journalists noted that during Constantine's innings, Nash was the only Tasmanian bowler to watch the West Indian closely and take note of his strengths and weaknesses, which led to his eventual success against the batsman.[23]

In September 1932 Nash married Irene Roles in Launceston, with City and Tasmania teammate Ted Pickett acting as best man.[24] Due to the strict sectarianism of the 1930s, there was some controversy as Irene was a Protestant from one of Launceston's establishment families, and the wedding was held in a Protestant church. For years afterwards, Nash was subjected to a campaign by Catholic clergy to hold a Catholic wedding ceremony to legitimise his marriage but refused.[25]

Laurie and Irene had one child, Noelene, in January 1940.[26] Wallish states that it was thought that Laurie sought to have additional children but Irene was opposed.[26]

Called for throwing

On 26 January 1931 Nash was called for throwing in a match for Tasmania against Victoria at Launceston.[27] He later claimed that the throw was deliberate and came out of frustration with his fielders.[28] The call for throwing was early in the innings but Nash was able to recover from the incident to take 5/76 out of Victoria's total of 524.[29] Earlier in the same match Nash opened the batting and made 110, his highest first-class score.[30] It has been speculated by cricket historian Bernard Whimpress that Nash's decision to throw the ball may have been regarded by selectors as "part of a parcel of anti-social behaviours which told against regular selection" for either Australia or Victoria.[29]

Test debut

Nash was picked for Tasmania in two matches against the touring South Africans in January 1932. He failed to perform in the first match in Launceston, taking 1/68 and 2/45 and scoring 17 and 9.[31] However, Nash had a lively bowling performance in the Hobart match, making the ball come off the wicket at a great pace[32] and gaining match figures of 9/137, including two wickets in consecutive balls and breaking batsman Eric Dalton's jaw with a vicious bouncer on the hat-trick ball.[33] South African captain Jock Cameron praised Nash for his performance[34] as his bowling in the match was thought to be as quick and dangerous as any bowler in the world.[35]

Following the Hobart match Nash was included in the Australian side to make his Test debut, aged 21 years and 286 days, against South Africa at the Melbourne Cricket Ground beginning 12 February 1932. Nash was the first Tasmanian based player chosen to play for Australia since Charles Eady in 1902 and would be the last until Roger Woolley debuted in 1983.[36] Also making his Test debut for Australia was batsman Jack Fingleton while spin bowler Bert Ironmonger was recalled to the side.[37]

Nash's inclusion raised eyebrows, as The Argus wrote "The inclusion of Nash will occasion most surprise",[38] particularly as Nash was the only fast bowler chosen in the Australian team.[11] However Nash soon silenced any critics with a dangerous opening spell, capturing three of the first four South African wickets to fall[39] and 4 in the first innings for just 18 runs, followed by 1/4 in the second as South Africa were routed for 36 and 45.[40] The match was the first to finish in under six hours' play.[41]

Following the match, The Times commented favourably on Nash, reporting "Nash is a short, powerfully built man, … made the ball kick awkwardly, several balls getting up head-high, and in one spell before luncheon took three wickets for four runs. Nash has plenty of stamina for a fast bowler and is considered by some to be the man for whom the selectors are searching to fill the place of Gregory."[42]

Nash's performance also drew the interest of VFL clubs, as he was "said to be a better footballer than he is a cricketer."[43] Victorian Football League clubs Richmond and Footscray sought to recruit Nash[5] but the VFL considered Nash a Fitzroy player due to his time at Fitzroy Cricket Club.[43]

Bodyline

The 1932–1933 cricket season saw the Douglas Jardine-led England side tour Australia, with Nash expected to open the bowling.[44] English newspaper the News Chronicle stated that the emergence of Nash was "a grim prospect for England in its attempts to recover the Ashes."[45] Despite this, he was left out of what became known as the Bodyline series.

In the wake of England's tactics of sustained fast short pitched bowling at the body of the Australian batsman, Australian vice-captain Vic Richardson urged that Nash be brought into the Test team to "give the Poms back some of their own medicine."[46] Another Australian cricketer, Jack Fingleton, later wrote that the Australian selectors erred in not playing Nash, believing he was to be the best exponent in Australia of intimidatory fast bowling.[47] However, the Australian Board of Control for International Cricket, which had been protesting to the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) about the Bodyline tactics of Jardine, believed that the inclusion of Nash would only aggravate an already tense situation, and Australian captain Bill Woodfull thought Bodyline bowling to be unsportsmanlike and refused to use the tactic.[46]

Nash himself claimed that he could have ended Bodyline in two overs without needing to resort to a leg field, as he believed that the English batsman could not hook and a few overs of sustained, fast short pitched bowling would have caused England to abandon their Bodyline tactics.[48]

As it was, Nash only played one first-class game during the 1932–1933 season—for an Australian XI side against MCC at the MCG. Opening the bowling, Nash took 3/39 in the first innings and 0/18 in the second,[49] with reporters noting that he occasionally got a lot of bounce out of the wicket.[50] By this point Nash had played 17 matches for Tasmania, scoring 857 runs at 29.55 and taking 51 wickets at 31.96.[51] There was also talk, which proved unfounded, that Nash would be invited to join the touring team to Canada that Arthur Mailey was compiling.[43]

Move to Victoria

| Laurie Nash | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Laurie Nash playing for South Melbourne against Collingwood in 1936. | |||

| Personal information | |||

| Original team(s) | City (NTFA) | ||

| Debut |

Round 1, 1933, South Melbourne vs. Carlton, at Princes Park | ||

| Height | 175 cm (5 ft 9 in) | ||

| Weight | 82 kg (181 lb) | ||

| Playing career1 | |||

| Years | Club | Games (Goals) | |

| 1933–1937, 1945 | South Melbourne | 99 (246) | |

| Coaching career | |||

| Years | Club | Games (W–L–D) | |

| 1953 | South Melbourne | 18 (9–9–0) | |

|

1 Playing statistics correct to the end of 1945. | |||

| Career highlights | |||

| |||

| Sources: AFL Tables, AustralianFootball.com | |||

1933

Nash's football career continued to soar as several Victorian Football League clubs sought to recruit Laurie and Robert Junior.[52] South Melbourne, partly through its connection to Roy Cazaly and partly through its offer to Nash of an unprecedented £3 per match, accommodation and a job in a sports store, eventually won the battle for the Nash brothers' signatures for the 1933 VFL season.[52] Such was the interest in Melbourne in where Nash would play, when South Melbourne committee member Joe Scanlan travelled to Tasmania to sign Nash, he was smuggled aboard the steamer to avoid media attention.[53]

Nash moved to Melbourne in late 1932 and began playing cricket for South Melbourne Cricket Club[54] while waiting for his transfer to South Melbourne Football Club to be processed.[55]

The collection of players recruited from interstate in 1932/1933 became known as South Melbourne's "Foreign Legion".[56] Laurie starred in practice matches for South Melbourne but Robert Junior struggled and left the club prior to the start of the season to successfully play firstly for VFA club Coburg and then play and coach in country Victoria,[52] Wearing guernsey number 25, Nash made his VFL debut for South Melbourne against Carlton Football Club at Princes Park on 29 April 1933, aged 22 years and 362 days. A near-record crowd of 37,000 attended the match[53] and Nash immediately became one of the League's top players,[52] dominating matches from centre half-back. Due in large part to Nash's performance, South Melbourne finished the 1933 Home and Away season in second.[57]

Nash caused the South Melbourne coaching staff concern when he fractured two fingers in a match against Hawthorn two weeks before the final series.[58] Normally this type of injury would require a player to miss six weeks of football but Nash, who kicked six goals in the match,[59] missed just one week, returned for South's Semi-Final win against Richmond and was considered Best on Ground in South Melbourne's 1933 premiership win.[48] In the Grand Final Nash played at centre-half-back,[60] took thirteen marks and had twenty-nine kicks and dominated play.[61]

Nash was adjudged the finest defender since World War I by The Sporting Globe and was runner-up in the Best and Fairest at South Melbourne.[62]

A week after the Grand Final and still on a high from the premiership win, Nash opened the bowling for his district club South Melbourne against Australian captain Bill Woodfull's team, Carlton.[48] Mindful of the upcoming Test tour of England, Nash thought he could impress Woodfull by bowling him a series of short pitched deliveries,[48] eventually hitting him over the heart[63] (Woodfull had been hit just under the heart by Harold Larwood during the Bodyline series).[64] Nash dismissed Woodfull caught and bowled later that over for 15[63] but did not realise that "there was no way in the world Woodfull would take this wild and slightly uncouth cricketer with him to England in the current political climate (or perhaps any other)"[48] and was not chosen for the subsequent tour of England.

1934

Nash continued to play district cricket and was considered a strong possibility for the 1934 tour of England. He was chosen to play in the Bert Ironmonger/Don Blackie benefit match, which was also a Test trial, but was forced to withdraw after contracting rheumatism in his shoulder. Nash's replacement, Hans Ebeling, bowled well enough to secure a place in the tour squad instead.[65]

Following the 1933 Premiership success, hopes were high for the 1934 VFL season, which was known as the Centenary Premiership year, in recognition of one hundred years since the European settlement of Victoria.[66] Nash continued to move between centre half-back and centre half-forward, kicking 53 goals for the year (47 of which from 9 games)[67] as well as playing a significant role in South Melbourne full-forward Bob Pratt reaching a record 150 goals[68] (although later in life Pratt would joke that Nash only kicked to him once "but that was a mistake.")[69]

In August 1934, Nash was chosen to play for Victoria in an interstate match against South Australia at the MCG, replacing the injured Pratt.[70][71][72] Initially selected at centre half-forward, Nash had kicked 2 goals by the start of the second quarter when he was moved to full-forward to replace the injured Bill Mohr and proceeded to kick a further 16 goals to finish with 18 goals, a record for a Victorian player in an interstate match[73] and for the MCG as Victoria defeated South Australia 30.19 (199) to 14.10 (94).[60][74] Brownlow Medallist Ivor Warne-Smith wrote of Nash's performance; "his was a great achievement. He showed superb marking, good ground play, and accurate kicking. Some of his shots from left-foot snaps were gems… His performance has never been equalled."[71] He later claimed he would have kicked 27 goals that day but for the selfishness of the rovers who refused to kick to him.[75]

Following the inter-State match, Dr Bertram Langan Crellin (1876-1939), a former President of the Collingwood Cricket Club and former Vice-Persident and Medical Officer of the Collingwood Football Club,[76] who had attended the birth of Nash, publicly apologised to the South Australian side, claiming part responsibility for the mayhem that had been inflicted by Nash.[77]

South Melbourne finished the home and away series in third position, defeated Collingwood by three points in the first Semi-Final and Geelong by 60 points in the Preliminary Final, with Nash in brilliant form in the drizzling rain, kicking four goals.[78]

Going into the 1934 Grand Final, South Melbourne were favourites to retain the premiership but while Nash kicked six goals and was adjudged one of the best players of the match, South Melbourne were defeated by Richmond by 39 points.[66] Such was the surprise around South Melbourne's loss, there were post-match rumours of South players being offered and accepting bribes to play poorly – and Bob Pratt and Peter Reville angrily confronted teammates who underperformed.[79]

1935

Nash resigned his position at the sports store and followed in his father's footsteps by joining the Victorian police force on 14 January 1935,[80] and at 5'9" only just reached the minimum height requirement.[81] Constable Nash served in the South Melbourne area for two years before resigning,[82] having made no arrests in that time.[83]

Nash continued to cement his reputation as one of the top footballers in the country, being called "the most versatile player in Australia",[84] as, in addition to playing at centre half-back and centre half-forward, he successfully played in the ruck.[85]

Named at centre half-back for Victoria in the game against Western Australia, Nash arrived in Perth with such a severe cold he was unable to train in the lead up to match.[86] Nash injured his knee and ankle in Victoria's win over Western Australia in Perth in early July and was unable to train for a week.[87] While Nash did not miss any matches due to the injuries, they bothered him throughout the season and he was forced to miss South Melbourne Footballers' weekly dance at the Lake Oval Social Hall.[88] Although carrying injuries, Nash continued to show his versatility, playing around the ground[85] and led South Melbourne to the Grand Final, their third in a row, only to be defeated by Collingwood.[89]

At the end of the 1935 season, Nash was adjudged the Best Player in the VFL by the Sporting Globe,[90] yet only came runner-up to Ron Hillis in South Melbourne's Best and Fairest.[91]

1936

Appointed vice-captain of South Melbourne, Nash had his best Brownlow Medal result in 1936, receiving ten votes and finishing equal sixteenth behind winner Denis Ryan,[92] while at South Melbourne, Nash was voted runner-up in the Best and Fairest and was runner-up in the Leading Goalkicker award.[93] Nash however was considered by many judges as the best footballer in Australia, being adjudged "VFL Best Player" by the Sporting Globe, "VFL Footballer of the Year" by the Melbourne Herald and "VFL Best Player of the Year" by The Australian,[90] while newspapers reported that crowds "gasped" at the remarkable things he was able achieve with the ball.[94]

South Melbourne finished the year as Minor Premier but lost to Collingwood in the Second Semi-Final, although Nash, at centre-half-back, was listed as one of South's best players in the match.[95] South then won the Preliminary Final against Melbourne, with the dominance of Nash, again at centre-half-back, over his opponent Jack Mueller, himself one of the VFL's leading players, deciding the result of the final.[96]

For the fourth season in a row, South Melbourne reached the Grand Final, only to lose, for the third season in a row, to Collingwood for the second time in a row.[97] Nash kicked one goal in the Grand Final and was adjudged one of South's best players but Collingwood's Jack Ross's dogged tagging of Nash throughout the match was considered the decisive factor in Collingwood's win.[95]

1937

Nash was best on the ground.[99]

Nash was selected as captain of South Melbourne for the 1937 season to replace the retiring Jack Bisset,[100] becoming part of the first father and son team to captain a VFL/AFL side.[101] It is thought that South Melbourne's newly appointed coach Roy Cazaly influenced the selection of Nash as captain, as Cazaly, Nash's coach in Tasmania, believed Nash to be the best footballer ever.[102] There was some controversy over Nash's selection as captain, as it had been expected that vice-captain Brighton Diggins would be named captain. In response, Diggins quit South.[103]

South Melbourne did not enjoy the same level of success it had in the past four seasons, dropping to ninth position as retirements of some its key players from the previous four seasons, as well as injuries meant Nash was forced to play a lone hand for much of the year.[104] Nash won the club goal kicking award with 37 goals.[100]

Test comeback

Nash spent five years out of the cricketing spotlight (although he dominated Melbourne district cricket, the Victorian selectors refused to select him and he never played a Sheffield Shield match). In 1936–1937 he topped the district cricket bowling averages.[105]

Nash was chosen for Victoria against the touring English cricket team and responded with figures of 2/21 and 2/16 and had the tourists ducking and weaving with "several head and rib-hunting deliveries an over".[106] By playing for Victoria in this match, Nash became the first person to represent two different states in cricket and Australian rules football. He remains one of only three players to do so (the others being Keith Miller and Neil Hawke).

In response to his bowling performance, Nash was picked for the deciding Fifth Test of the 1936–1937 Ashes series at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, with the sides locked at 2–2 in the series.[107] His selection invoked complaints from the touring English side, where it was reported that a "feeling bordering on panic" had arisen at the thought of facing Nash during the Test.[107] England captain Gubby Allen pressed for Nash's banishment from the Australian team,[107] organising a private lunch with Bradman, then Australian captain.[106] Bradman refused to omit Nash, believing "his presence in the team would be a psychological threat to England whether he bowled bouncers or underarm grubbers".[106] Allen then approached the Australian Board of Control.[106] It has been suggested that the Board of Control wanted to accede to Allen's demand and veto Nash's selection but were forced to relent when the selectors threatened to resign if Nash was not included.[105] Finally, Allen informed the umpires that if Nash was to bowl one ball aimed at the body, he would immediately bring his batsmen off the ground.[108]

Nash claimed 4/70 and 1/34 and scored a sedate 17 in seventy-five minutes (disappointing the crowd which "was expecting fireworks from him")[109] as Australia clinched the series.[110] Nash also took a number of catches, including Wally Hammond off Bill O'Reilly and a spectacular catch to dismiss Ken Farnes, the last England batsman,[111] pocketing the ball and a stump as souvenirs.[112] When later asked about his inclusion, Nash replied "They knew where to come when they stood 2-all in the rubber."[105]

The media was full of praise for Nash's performance in the Test, claiming that Nash was a much more reliable fast bowler than his "erratic" opening partner Ernie McCormick.[113] Nash was praised for his stamina, his ability to keep his footing and his direction during long bowling stints and his vicious yorker, which he used to dismiss Leslie Ames in the first innings and Joe Hardstaff junior in the second.[113]

Bradman later wrote that Nash's bowling was scrupulously fair and that any bouncers were few and adhered to the spirit of cricket.[114]

Cricket wilderness

| Charles Marriott (ENG) | 8.72 |

| Frederick Martin (ENG) | 10.07 |

| George Lohmann (ENG) | 10.75 |

| Laurie Nash (AUS) | 12.60 |

| John Ferris (AUS/ENG) | 12.70 |

| Tom Horan (AUS) | 13.00 |

| Harry Dean (ENG) | 13.90 |

| Albert Trott (AUS/ENG) | 15.00 |

| Mike Procter (SA) | 15.02 |

| Jack Iverson (AUS) | 15.23 |

| Tom Kendall (AUS) | 15.35 |

| Alec Hurwood (AUS) | 15.45 |

| Billy Barnes (ENG) | 15.54 |

| John Trim (WI) | 16.16 |

| Billy Bates (ENG) | 16.42 |

Source: Cricinfo Qualification: 10 wickets, career completed. | |

Following the Test, Nash was selected for Victoria for their match against South Australia at the Adelaide Oval in what would have been his first Sheffield Shield match.[115] However, Nash was forced to withdraw and fly to Tasmania following his wife Irene's sudden collapse in Hobart with peritonitis.[116]

At the start of the 1937–1938 cricket season, it was expected that Nash would be chosen for the 1938 Ashes Tour, with one journalist stating that if he was not selected, the team "would not be truly representative of our nation's real cricketing strength."[117] Nash continued to terrorise batsmen in district cricket, including the rare occurrence of taking all 10 wickets in an innings (for 35 runs) for South Melbourne against Prahran in 1937–38,[105] but was not selected for Victoria throughout the season. Nash's non-selection for Victoria led some Victorian Cricket Association delegates to publicly question why "the best fast bowler in Australia, and probably the world, is not chosen to represent Victoria" and demand that the Victorian selectors explain their non-selection of Nash.[118]

Nash's first-class career ended at the age of 26. His career Test figures 10 wickets at 12.60 places him fourth on the list of averages for bowlers to have taken 10 or more Test wickets (and the best by an Australian). His 22 first-class matches reaped 69 wickets at 28.33 and 953 runs at 28.02. His district cricket career of 63 matches netted 174 wickets at 14.95.[119]

A young Keith Miller also played for the South Melbourne Cricket Club and gained his first wicket in district cricket from a catch by Nash.[120] Miller later declared that the non-selection of Nash as a regular Test player was "the greatest waste of talent in Australian cricket history", adding that Australian captain Don Bradman wanted Nash in the side to tour England in 1938 but that Nash "suffered injustices at the hands of high-level cricket administration", who refused to consider his selection.[1]

The reasons given for the administrators' disinclination towards Nash include his reputation for blunt speech, his abrasive personality, which included sledging, and even the fact that he wore cut off sleeves, which was considered a serious faux pas in the 1930s.[121] Nash himself believed it was due to his working-class background, saying "I didn't wear the old school tie. I was a working man's son. I didn't fit in".[122]

Transfer to Camberwell

Prior to the 1938 season, the Victorian Football Association (VFA), the second-tier senior football competition in the state, made an ambitious break from tradition in what was ultimately a successful ploy to improve its popularity: it legalised throwing the ball in general play and made a few other rule changes to create a distinct and faster variation of Australian rules football, and ended the legal framework which required players to obtain a clearance when switching from the VFL to the VFA (or vice versa).[123][124] On 31 March Nash caused a sensation when he became the first VFL player to defect under this schism,[125] transferring from South Melbourne to Camberwell without a clearance.[126] Nash was already one of the highest paid players in the VFL, but accepted an offer of £8/week to captain-coach the Camberwell Football Club, £3/week to captain-coach the sub-district Camberwell Cricket Club and a job as a Camberwell Council official.[127]

South Melbourne and the VFL objected to the transfer and South Melbourne sent out a public appeal for a job for Nash that would match that offered by Camberwell but nothing suitable was forthcoming.[128] There were also threats of legal action against Nash and Camberwell, which did not eventuate,[127] although for playing in another competition without a clearance, Nash was banned from playing in the VFL competition for three years – a suspension which meant he would have to sit out of all football (both VFA and VFL) for three years if he wished to return from the VFA to the VFL.[129]

Nash was immediately appointed captain of Camberwell and quickly became one of the most popular figures in the VFA, drawing large crowds to even practice matches.[130] Playing mainly at centre-half-back in his first season but later in the forward-line, Nash was runner-up in the 1938 Camberwell Best and Fairest and won the 1939 Best and Fairest;[131] and in 1939, he finished second in both of the VFA's Best and Fairest awards: the Recorder Cup and VFA Medal.[132][133] Nash spent four seasons at Camberwell, where he played 74 games and kicked 418 goals,[134] including 100 in 1939[135] and 141 in 1941.[136] At the start of the 1940 season Nash was still considered amongst the best footballers in the country[137] and, with the transfer of former South Melbourne teammate Bob Pratt and Collingwood full-forward Ron Todd to rival VFA sides Coburg and Williamstown respectively, there was talk that the VFA would now match the VFL for crowds.[137]

Nash was officially appointed Captain/Coach of Camberwell Cricket Club on 19 September 1938[138] and his debut for the club in the summer of 1938–1939 meant that he was the first person to be paid for playing grade cricket in Australia.[139]

War service

.jpg.webp)

Nash did not rush to enlist in the Australian armed forces on the outbreak of war in 1939. While there was no public statement from Nash, it is thought that with a family to support and an Irish Catholic anti-pathy to the British, Nash did not feel an urgency to fight.[140] However, following the commencement of the war against Japan, Nash enlisted on 2 February 1942.[141]

Realising the potential public relations coup in having a star sportsman enlist, officers recommended that Nash be seconded to the Army School of Physical Training (where Don Bradman had been given a commission), which offered greater pay and rank and ensured that Nash would not be posted overseas, away from family.[142] Additionally, a medical examination detected osteoarthritis in both his knees, derived from the number of injuries he sustained throughout his footballing career.[143] Nash refused, stating that he did not wish to be treated differently from ordinary recruits,[144] and enlisted in the Second Australian Imperial Force, gaining the rank of Trooper.[141]

Nash was posted to the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion, which had seen action in the Syria-Lebanon and the Netherlands East Indies campaigns.[145] The 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion was sent to the South West Pacific theatre, supporting the 7th Division in the New Guinea campaign[146] and fought in the Finisterre Range campaign in the advance to Lae.[145]

Throughout his tour of duty Nash had been wary of preferential treatment towards him due to his fame and opposed any attempts to promote him, which he believed he did not deserve.[147] However, a jeep crash resulted in further injury to Nash's knees and ultimately led to a medical discharge from the Army on 18 February 1944.[141] Following his return to Australia, Nash sold War Bonds[148] and appeared at war-related charity functions, including one where he raised an additional £100 by singing to the large crowd.[149]

Although Nash would claim that he was never prouder than when he was a soldier,[147] always wore his Returned Services League (RSL) badge and eagerly attended reunions of the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion, he never marched on Anzac Day or applied for the campaign medals for which he was eligible.[150]

Postwar sport

Although out of shape and with arthritic knees, Nash announced that he was making a football comeback in 1945.[151] He sought to return to South Melbourne, rather than Camberwell,[152] but Camberwell declined Nash's transfer application[153] and both clubs stated that they would be naming Nash in their respective sides for Round 1.[152] An impediment to Nash's return to South Melbourne arose as a result of Nash having played two games for his old boy scout troop, the 6th Melbourne Scouts, while on leave in mid-1942; these games were considered competitive, and playing in them meant that Nash had not sat out of football for the three years required to serve the suspension he had received for crossing to Camberwell without a clearance.[154] After an appeal by South Melbourne, a special meeting of the VFL was held to amend the rules so ex-servicemen would not be penalised for playing in minor matches.[155] The amendment was made the day before the commencement of the 1945 season, allowing Nash to take his place for South Melbourne in their Round 1.[155]

Nash was slower and more portly than he was in the 1930s, short of match practice and forced to spend most Sundays in hospital having fluid drained from his injured knees swollen from the exertions of the day before,[156] forcing South Melbourne coach Bull Adams to nurse Nash through the season.[156] Additionally, in the Round 5 match against Footscray, he tore the webbing between his fingers which later became infected, causing him to miss the Round 6 match against North Melbourne and although Nash wore a special leather glove to protect his hand, the injury would trouble him for the rest of the season.[156] Despite these setbacks, Nash could still be a match winner and many opposition players saw him as the key player for South Melbourne.[157] Nash's best return for the year was seven goals against St Kilda in Round 12 and he twice kicked six goals in a match; against Geelong in Round 15 and Fitzroy in Round 18.[158] When an opposition player did well against Nash, it was something to savour; years later leading Richmond player Don "Mopsy" Fraser wrote "Trouncing Nash does a lot for your confidence, even an ageing Nash."[159]

South Melbourne won the minor premiership in 1945 and reached the 1945 VFL Grand Final, where it lost to Carlton.[160] Named at full-forward, Nash was the oldest player in the Grand Final at 35 years and 150 days. The match, known as 'the Bloodbath', was notorious for its onfield violence. For his part, Nash king-hit Carlton captain Bob Chitty in the final quarter with what he later described as the sweetest punch he had ever thrown, knocking Chitty out, breaking his jaw and leaving a large wound over his left eye which required several stitches;[161] as the umpire was unsighted, Nash went unreported over this incident.[162] Nash was generally ineffective on the day, and his opponent Vin Brown was a consensus pick for best player on ground.[163][164] Nash was described as a "sad figure… age and injury had reduced him to almost a caricature, a lion in winter simply going through the motions. His body was no longer capable of performing the feats that a decade earlier had seen him feted as the finest footballer to ever play the game."[165]

Nash played 17 games for South in 1945, kicking 56 goals. This left him with 99 VFL matches and 246 goals in his career. Nash also played three matches for Victoria, kicking 19 goals.[166]

On 18 February 1944, the day he was discharged from the Army, Nash played an internal trial cricket match for South Melbourne,[167] although he had not played competitive cricket for four years. However, he did not play another first XI district match for South Melbourne after the war.[119]

Post-VFL footballing career

Nash trained with South Melbourne during the 1946 pre-season[168] but ultimately retired from VFL football to accept a position as captain-coach of the Ovens and Murray Football League side Wangaratta for a salary of £12 per week, four times the wage he would have received playing for South Melbourne.[169] The high wage also meant that Nash was not required to find additional employment to cover his family's expenses, and in so doing, became one of the first fully professional Australian rules football players.[168]

Nash not only led Wangaratta to a premiership[105] but, as a favour to a friend, also coached another country side, Greta in 1946, leading them to a premiership in the Ovens and King Football League,[136] becoming one of the few people to have coached two different teams to a premiership in the same season.[170] Nash is still remembered in Greta for placing a football in a cowpat and placekicking it over a tall gum tree.[171]

In 1947, Nash was appointed captain-coach of Casterton, in western Victoria, once again at a wage of £12 per week.[172] He took Casterton to a grand final that season, losing by a point.[173] The grand final would be Nash's final official game as a player, although he did play in charity matches for some years.[174]

South Melbourne coach

Nash's success as a coach in country football lead South Melbourne to appoint him as coach for the 1953 VFL season.[175] Following his appointment, Nash confidently predicted that he would coach South Melbourne to a premiership that year[176] and at the halfway point of the season South were tipped to play in the finals but injuries to key players led to five consecutive losses[177] and at the end of the season South Melbourne had won nine games and lost nine games to finish eighth in the twelve team competition.[178]

There was some criticism of Nash as a coach as he apparently could not understand how players were unable to do things on the football field that came to him naturally.[179] Nash had signed a two-year contract, yet the South Melbourne committee re-advertised the position of coach following the end of the 1953 season and while Nash applied, he was not reappointed.[180] Fellow South Melbourne champion Bob Skilton claimed that had Nash been given time, he "would have become one of the all-time great coaches".[181]

Post-sporting career

Following his retirement from coaching, Nash became involved in the sporting media. He wrote a column for the Sporting Globe newspaper,[182] spoke at sportsmans' nights[183] and made regular television appearances, including on World of Sport, to comment on Australian rules football and point out that there had not been a player of his ability in the VFL since his retirement.[184]

In his newspaper column, Nash did not shy away from controversy, claiming on one occasion that Sir Donald Bradman had openly "roasted" a number of leading Australian cricketers for their performance during a Test.[185] The claim sparked an angry response from Bradman, who claimed "everything in the article as attributed to me is completely without foundation in every particular."[185]

In addition to his positions in the media, Nash was also a publican, which proved so financially successfully he was able to pay cash for a house in the upmarket Melbourne suburb of South Yarra.[186] An altercation with a drunken patron resulted in a broken left hip and forced Nash to sell his hotel, the Prince Alfred in Port Melbourne[187] and gain employment as a clerk in the Melbourne Magistrates Court,[68] a position he held until his mandatory retirement at 65.[131]

Along with fellow former Test cricketer Lindsay Hassett, Nash voluntarily served on the executive committee of the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria and worked closely with the Aboriginal community of Melbourne, partly in recognition of his old friend Doug Nicholls, a former VFL footballer and leading figure in the Indigenous community.[188] He also turned his interest to fishing, stating that he felt "edgy" if he did not go fishing a couple of times a week.[186]

Nash strongly opposed the relocation of South Melbourne Football Club to Sydney (renamed the Sydney Swans) in 1981, considering it a repudiation of the proud South Melbourne he had helped create.[189] Nash stated that he had given fifty years to South Melbourne but due to the relocation they had now lost him forever[190] and refused to attend Swans matches for many years, relenting only shortly before his death to attend a match between Sydney and Footscray.[191]

Nash was forced to have a pin and plate inserted in his broken left hip and as a result walked with a profound limp.[186] He also began to drink and eat more and stopped his exercise routine, leading him to become bloated, "like an old, red balloon that had been slightly let down".[12]

Nash's father Bob Senior collapsed and died in 1958 while at the MCG watching Collingwood win the 1958 VFL Grand Final. Laurie Nash later said that it would have been the perfect way for his father to die.[192] Nash's brother Bob Junior died of emphysema in the early 1970s,[192] while in 1975 Irene Nash, who had been in poor health for some time, died, leaving Nash heartbroken. Every day for five years he visited the cemetery where her remains were scattered.[193]

In 1980 Nash met twice widowed Doreen Hutchison and eventually moved in with her.[188] While they never married, Doreen answered to the name "Mrs Nash".[181] When Doreen died suddenly from a heart attack in 1985, Nash's health quickly deteriorated and he suffered a stroke in early 1986.[194] Visitors to Nash's bedside remarked that Nash could not believe his own mortality.[195]

Following a succession of strokes, Nash died in the Repatriation Hospital in Heidelberg, Victoria on 24 July 1986, aged 76.[191] Survived by his daughter Noelene and grandsons Anthony and Simon,[196] a service for Nash was held at a Catholic church in Melbourne and his cremated remains were scattered at Fawkner Memorial Park, near that of his wife Irene.[197]

Style

Nash's great sporting success can be partly attributed to his self-confidence. Once, when asked who was the greatest footballer he had ever seen, Nash replied "I see him in the mirror every morning when I shave".[198]

[The conversation then turned] to former South Melbourne great (and Test cricketer) Laurie Nash, who was renowned, besides for his prodigious talent, for being on fairly good terms with himself.

[Bob] Davis: "We were at the Lake Oval one day, and a kid, I think it might have been Billy Gunn, took a mark about 30 yards out straight out in front, and I said to Laurie, who was long retired – I was standing with him – I said: 'Will he kick this goal?' And he said: 'I don't know if he will, but I would, in my pyjamas, dressing gown and carpet slippers, left or right foot. And I mean now!' " The Age, Saturday, 28 June 2008.[199]

Yet, whilst Nash tended to sound arrogant in public, he was very modest about his success in private; in fact, his daughter Noelene was not aware of her father's sporting success until aged 12 when a friend's father told her.[200]

Footballing style

Nash was a superbly fit athlete who never smoked, drank rarely, and dedicated himself to a punishing exercise regime; something rare in 1930s sports circles.[12]

Legendary Richmond Football Club player and coach Jack Dyer asserted that Nash was "Inch for inch, pound for pound, the greatest player in the history of Australian Rules",[201] adding "He was the only man I knew who could bite off more than he could chew and chew it."[190]

In the view of champion Collingwood full-forward Gordon Coventry, whose record of 1299 VFL career goals between 1920 and 1937 would not be surpassed for 62 years, if Nash had played at full-forward for his entire career, he would have kicked more goals than anyone, Coventry included.[202] In 1936 Coventry stated that Nash was the best player he had seen; "No player is more versatile, for he can play anywhere. He is fast, has great control of the ball, kicks with either foot and has that little bit of "devil" so essential in the makeup of a champion of to-day."[203]

Fellow footballer Vic Richardson wrote in 1968 that Nash "was faster than any player I have seen in getting the ball moving to players running on. Add his high marking ability and speed to his quick thinking and you had a player who practically originated today's style of play and one who would be unbeatable at it."[204]

In retirement, Nash was asked why he never won a Brownlow Medal (the award for the Best and Fairest player in the VFL). He replied, "I was never the best and fairest but I reckon I might have been the worst and dirtiest. I played it hard and tough."[186]

Cricketing style

Nash's bowling action has been described as letting "the ball go with a furious arm action, as if a fortune depended on every ball",[205] making "the ball fizz as he charged through the crease at a speed that always appeared likely to topple him over."[205] Another witness added "there was little beauty in his bowling. He sprinted to the wicket faster than most bowlers but had an almost round-arm flipping delivery" which made him the most dangerous bowler in Australia on lively pitches.[206] In 1990, famed Australian historian Manning Clark recalled Nash's bowling when he wrote of the period in the 1930s when he was an opening batsman for the University of Melbourne in Victorian district cricket and had to draw on his mother's strength to help him "face Laurie Nash at the South Melbourne ground without flinching."[207]

Nash was also complimented on his control, stamina and "an ever present confidence in his ability", which, combined with his speed, made him a formidable bowler.[208] Additionally, Nash was also praised for his fielding in almost any position, with one scribe referring to his "amazingly athletic ability".[209]

Nash's batting stance was described as "peculiar".[109]

His bat touches the turf in line with the off-stump, but his feet are well clear of the leg stump. He grips the bat near the tip of the handle, and it gives an impression that the bat is inordinately long.[109]

After making a duck in the first innings of the match between Tasmania and the touring Australian side in March 1930, members of the Australian side advised Nash to change his stance, stating that it was too unorthodox to be successful.[210] Nash ignored this advice[210] and promptly scored 93 in the second innings of the match.[211]

Other sports

Nash also excelled in other sports, winning awards in golf, tennis and quoits, including the Australian cricket team's 1932 deck quoits championship at the Oriental Hotel in Melbourne, defeating Clarrie Grimmett in the final.[186] Nash's natural skills in any sport he tried led former first-class cricketer Johnnie Moyes to call Nash "one of the finest all-round athletes of the century".[212]

Honours and legacy

In addition to the awards he received during his playing career, Nash was awarded accolades for his sporting prowess after his retirement.

Nash was made a life member of South Melbourne Football Club in 1960[93] and following his death, the Sydney Swans wore black armbands in their match against Carlton,[197] named their Best and Fairest Award the "Laurie Nash Medal",[213] in 2003 named him at centre-half-forward in their "Team of the Century"[214] and in 2009 named him as an inaugural member of their Hall of Fame.[215] The central place Nash held at the Swans was illustrated in 2005, when following Sydney's grand final win, a cartoon appeared in the Melbourne Herald Sun, featuring Swans players surrounding Nash, who was wearing his South Melbourne guernsey and was drinking from the premiership cup.[216] In 1987 Nash was made a foundation member of the Tasmanian Sporting Hall of Fame[17] and named at centre-half-back in the Tasmanian Australian rules "Team of the Century".[217] When he was selected for the Australian Football Hall of Fame in 1996, the summary commented "One of the most gifted players ever, his career was half as long as many but it shone twice as brightly as most. Considered by many judges (himself included) the best player in the land…".[218][219] In 2003, he was named at centre half forward in the Camberwell Team of the Century.[220]

Test batsman Merv Harvey once claimed that his greatest achievement was scoring runs off Nash's bowling, which he classed as the fastest he had ever faced, in a club match.[221] Author Ian Shaw called Nash "perhaps the greatest all-round sportsman Australia has ever produced",[222] while some fans old enough to remember Nash at his peak list him as the greatest player they ever saw[201][223] and a football journalist who failed to include Nash in a "Best Ever" list was the target of a letter writing campaign from elderly fans.[201]

Additionally, by way of a folk memorial, he is recalled in the Australian vernacular term "Laurie Nash", rhyming slang for "cash"[224] and is mentioned in the 1993 novel Going Away by award-winning journalist Martin Flanagan.[225]

See also

Footnotes and citations

- Miller, Keith in Foreword, Wallish, p. iv.

- Wallish, p. 10.

- Wallish, p. 11.

- "M. Nash". Blueseum. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- Shaw, p. 124.

- "Hamilton v Marylebone Cricket Club in 1920/21". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- Wallish, pp. 11–12.

- Wallish, p. 12.

- Wallish, p. 14.

- Wallish, p. 20.

- Dunstan, p. 156.

- Flanagan, M. "Laurie Nash – The Genius", The Melbourne Age, p. 8, 5 May 1998.

- "Cricket", The Argus, 11 February 1929, p. 11.

- Wallish, pp. 23–24.

- Wallish, p. 26.

- "Scorecard, Tasmania v Victoria in 1929/30". CricketArchive. Retrieved 6 May 2008.

- Tasmanian Sporting Hall of Fame, p. 80.

- Wallish, p. 359.

- Piesse (1993), p. 33.

- "Laurie Nash – Senior Football Career in Tasmania". R. Smith. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- "Tasmania v West Indies in 1930/31". CricketArchive. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- Findley, R. "Pickett's death marks a record innings", Sunday Tasmanian, 8 February 2009, p. 73.

- Page, p. 107.

- Wallish, p. 68.

- Wallish, p. 322.

- Wallish, p. 214.

- "Tasmania v Victoria in 1930/31". CricketArchive. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- Ric Findlay. "The Companion to Tasmanian History". Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- Whimpress, p. 42.

- "Laurie Nash". Cricinfo. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- "Scorecard, Tasmania v South Africans in 1931/32". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- "South Africans in Tasmania", The Times, 16 January 1932, p. 4.

- "Scorecard, Tasmania v South Africans in 1931/32". CricketArchive. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- Page, p. 108.

- Page, p. 101.

- Smith, p. 187.

- "Changes in the Australian Team", The Times, 4 February 1932, p. 4.

- "Ironmonger Chosen. Nash and Fingleton Included", The Argus, 4 February 1932, p. 7.

- Perry (1995), p. 253.

- "Australia v South Africa Fifth Test". CricketArchive. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- Piesse (2003), p. 126.

- "CRICKET: Low Scoring at Melbourne", The Times, No.46056, (Saturday 13 February 1932), p.5, col.F.

- Old Boy, "Position of L. Nash", The Argus, 16 February 1932, p. 11.

- Wallish, pp. 76–77.

- Wallish, p. 53.

- Perry (1995), p. 297.

- Fingleton, p. 121.

- Frith, p. 413.

- "Australian XI v Marylebone Cricket Club, 1932/33". CricketArchive. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- "Struggle For Runs", The Argus, 19 November 1932, p. 23.

- "First-class Bowling For Each Team by Laurie Nash". CricketArchive. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- Shaw, p. 125.

- Main (2005), p. 109.

- "Tasmanian Bowler Joins South Melbourne", The Canberra Times, 6 October 1932, p. 1.

- Fiddian (2004), p. 8.

- The caricature at the foot of page 10 of Table Talk (22 June 1933) was created by Richard "Dick" Ovenden (1897–1972). From left to right those represented are: Jack Bisset, the team's captain; Dick Mullaly, the club's secretary; Brighton Diggins, from Subiaco (WAFL); Bert Beard, from South Fremantle (WAFL); Bill Faul, from Subiaco (WAFL); Jim O'Meara, from East Perth (WAFL); Frank Davies, from City (NTFA); Laurie Nash, from City (NTFA); John Bowe, from Subiaco (WAFL); Jack Wade, from Port Adelaide (SANFL); Ossie Bertram, from West Torrens (SANFL); and Wilbur Harris, from West Torrens (SANFL).

- Atkinson (1996), p. 123.

- Main (2006), p. 95.

- Wallish, p. 92.

- Holmesby, Russell; Main, Jim (2002). The Encyclopedia of AFL Footballers: every AFL/VFL player since 1897 (4th ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Crown Content. p. 476. ISBN 1-74095-001-1.

- Main (2006), p. 96.

- Wallish, pp. 360–361.

- "Two Centuries", The Courier Mail, 9 October 1933, p. 9.

- Frith, p. 179.

- "Spectator", The Argus, 10 February 1934, p. 25.

- Atkinson (1996), p. 131.

- Eva, B. "Bobby Dazzler", The Sunday Age, 11 October 2009, Sport Section, p. 24.

- "Laurie Nash", The Herald (Melbourne), 21 September 1974, p. 27.

- Fiddian (1996), p. 30.

- Victoria's Team of Champions, The Age, (Monday, 13 August 1934), p.6.

- Warne-Smith, I., "Crushing Defeat", The Argus, 13 August 1934, p. 11.

- "Nash's Feat: Five Goals Off Australian Inter-State Record", The Age, 13 August 1934, p.6.

- The overall record is 23 goals by East Perth footballer, Hugh "Bonny" Campbell for Western Australia, against Queensland, on 12 August 1924 (Football Carnival: Another Record Score: W. Australia 43.19; Queensland 2.1: Campbell Gets 23 Goals, The (Burnie) Advocate, (Wednesday, 13 August 1924), p.3).

- "Melbourne Match – L. Nash 18 goals", The Canberra Times, 13 August 1934, p.3.

- Piesse (1993), p. 197.

- A Wonderful Record: A Sportsman of Yesteryear, The Frankston and Somerville Standard, (Saturday, 4 January 1930), p3.

- "Nash's 18 Goals: Dr. Crellin takes the blame", The Argus, 13 August 1934, p. 11.

- "South Melbourne Succeeds Again", The Canberra Times, 8 October 1934, p.4.

- Main (2009), p. 114.

- Wallish, p. 116.

- Boulton, M. (2007) "Ten Footy Policemen" Sunday Age, 10 June 2007.

- "L. Nash Leaves Police", The Argus, 25 March 1937, p. 17.

- Wallish, p. 189.

- Wallish, p. 126.

- "St Kilda and Richmond", The Mercury (Hobart), 30 May 1935, p. 16.

- "The Visiting Team", The West Australian, 21 June 1935, p. 24.

- "L. Nash Unable to Train", The Age, 3 July 1935, p. 7.

- "Nash to be tested", The Age, 5 July 1935, p. 3.

- Atkinson (1996), p. 136.

- Wallish, p. 360.

- "Football Trophies", The Argus, 17 October 1935, p. 13.

- "D. Ryan wins Brownlow Medal", The Argus, 10 September 1936, p. 11.

- Wallish, p. 361.

- "Nash Brilliant", The Argus, 16 July 1936, p. 15.

- Atkinson (1996), p. 140.

- Atkinson (1996), p. 139.

- Atkinson (1996), p. 142.

- The Sporting Globe, (Wednesday, 30 June 1937), p.8.

- Best and Fairest, The Argus, (Monday, 28 June 1937), p.4.

- Smith, p. 188.

- Wallish, p. 162.

- Wallish, p. 156.

- Main (2009), p. 120.

- Wallish, p. 168.

- Anderson, J. "Nash a Wasted Talent", Herald Sun, 25 June 1998.

- Perry (1995), p. 401.

- Hendry, H. The Truth, "Did Allen Want Nash Out?", 25 February 1937.

- Frith, p. 414.

- Not Out, "Debits and Credits", The Referee (Sydney), 4 March 1937, p. 15.

- "Australia v England in 1936/37 Fifth Test". CricketArchive. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- Bradman Albums Vol. II – 1935–1949.

- "Tame Ending", The Canberra Times, 4 March 1937, p. 1.

- "Australia Retains Ashes Through Rare Batting", The Referee (Sydney), 4 March 1937, p. 15.

- Bradman (1994), p. 95.

- "Cricket: Sheffield Shield", The Times, 13 March 1937, p. 6.

- Wallish, p. 155.

- Wallish, p. 181.

- "Dr Hartlett's Plea", The Argus, 10 November 1938, p. 18.

- "VCA 1st XI Career records 1889–90 to 2014–15, N-R" (PDF). Cricket Victoria. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Palmer, S. "Blues Legend Still in Swing", Herald Sun, 10 May 1998.

- Nash cut off his sleeves to avoid them flapping as he ran into bowl, Wallish, p. 304.

- Smith, p. 18.

- Rover (16 April 1938). "Crowds will be attracted by new rules". The Argus. Melbourne. p. 22.

- Percy Taylor (16 February 1938). "Football experiments". The Argus. Melbourne. p. 24.

- Percy Taylor (31 March 1938). "To leave League – Nash joins Camberwell". The Argus. Melbourne. p. 1.

- Booth, R. (1997) "History of Player Recruitment, Transfer and Payment Rules in the Victorian and Australian Football League", Australian Society For Sports History Bulletin, No. 26, June 1997.

- "Naughty Nash", The Canberra Times, 4 April 1938.

- Priestley, p. 348.

- Shaw, p. 51.

- "Big Crowd Sees Nash in Practice Match", The Argus, 4 April 1938, p. 18.

- Wallish, p. 362.

- "Cutting wins medal". The Argus. Melbourne. 14 September 1939. p. 18.

- Rover (18 September 1939). "Northcote loses – exciting game". The Argus. Melbourne. p. 15.

- Wallish, p. 358-59.

- Atkinson (1982), p.124.

- Hobbs, G. & Palmer, S., p. 23.

- "Laurie Nash again", The Age, 20 April 1940, p. 17.

- The Argus, 19 September 1938, p. 9.

- Wallish, p. 196.

- Wallish, p. 232.

- "WW2 Nominal Roll – Nash, Laurence, John". Government of Australia. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- Wallish, pp. 232–233.

- Wallish, p. 234.

- Wallish, p. 233.

- "2/2nd Pioneer Battalion". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- "Australia's Winter Allrounders: XI Test Cricketers who played Australian Rules football at the highest level". Cricinfo. Retrieved 6 May 2008.

- Wallish, p. 235.

- "Laurie Nash", The Argus, 26 September 1945, p. 11.

- Shaw, p. 57.

- Wallish, p. 238.

- Shaw, p. 127.

- "Two Clubs Still Claim Nash", The Argus, 6 April 1945, p. 11.

- "Camberwell and Nash", The Argus, 23 March 1945.

- "Transfer Application By Nash", The Argus, 12 April 1945, p. 13.

- "Last-Minute Permit For Nash", The Argus, 21 April 1945, p. 7.

- Shaw, p. 96.

- "Nash Shows How", The Argus, 9 April 1945, p.12.

- "Player round-by-round statistics 1945". Australian Football League. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- Hutchinson, p. 197.

- Atkinson (1996), pp. 177–178.

- Shaw, p. 166.

- Shaw, p. 167.

- Main (2006), p. 124.

- Shaw, p. 176.

- Shaw, p. 198.

- "AFL Hall of Fame Players". Australian Football League. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- "Nash", The Argus, 19 February 1944, p. 12.

- Wallish, p. 259.

- Wallish, p. 258.

- Anderson, J. (1997) "Maybe Laurie's Right, After All", Melbourne Herald Sun, p. 91, 28 July 1997.

- Flanagan, Martin (21 August 2010). "Ah, such is football life in Kelly country". The Age. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- "Football – Nash to coach Casterton". Portland Guardian. Portland, Victoria. 10 April 1947. p. 4.

- "Obituaries". Australian Football League Umpires Association. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- Wallish, p. 282.

- "Sydney Swans Honour Board". Sydney Swans. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- Main (2009), p. 165.

- Main (2009), p. 167.

- Rodgers, p. 390.

- Wallish, p. 286.

- Main (2009), p. 168.

- "Laurie Nash, 'the greatest of them all', dies, still estranged from his old club", Hobart Mercury, 25 July 1986, p. 25.

- Cousins, p. 277.

- Wallish, p. 314.

- Shaw, p. 225.

- Fingleton, J. "Did Test men get a roasting", The Straits Times, 11 January 1955, p. 14.

- Knox, K. "Never the fairest, but one of the best", The Age (Melbourne), 14 July 1970, p. 22.

- Wallish, p. 318.

- Wallish, p. 326.

- Piesse (1993), p. 251.

- "The Passing of a Legend", The Examiner (Launceston), 25 July 1986, p. 7.

- Hobbs, G. & Lovett, M. (1986) "South Legend Nash is Dead", The Herald (Melbourne), 24 July 1986, p. 22.

- Wallish, p. 339.

- Wallish, pp. 321–322.

- Wallish, p. 330.

- Wallish, p. 331.

- Wallish, p. iii.

- "Greats said goodbye to the 'greatest' of all, Laurie Nash", Football Times, 7 August 1986, p. 22.

- Reed, R. (2000) "Nash's cap comes home", Melbourne Herald Sun, 15 December 2000.

- Connolly, R., "THE CONNOLLY REPORT: The Legends' 50 Greatest", The Age, (Saturday, 28 June 2008), p.1.

- Wallish, pp. 171–172.

- Sheahan, M. (2008) "Lack of Longevity Nash's Downfall", Herald Sun, 15 March 2008.

- Holmesby & Main, p. 321.

- Coventry, G. "Coventry Selects Best Footballers", The Argus, 13 August 1936, p. 15.

- Richardson, p. 169.

- Pollard p. 776.

- Page, p. 101.

- Clark, p. 47.

- Smith, p. 183.

- Smith, p. 184.

- Page, p. 106.

- "Tasmania v Australian XI in 1929/30". CricketArchive. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- Smith, p. 190.

- Cordy, N, "Swans Badly Need Role Models", The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 September 1992, p. 56.

- "Capper huffed but Lockett's chuffed", The Age, 10 August 2003, p. 73.

- Lane, D. "Nash at home among Swans' greatest.", The Sunday Age, 19 July 2009, Sport Section, p. 5.

- Main (2009), p. 371.

- "For the Record", The Australian, 26 June 2004.

- Hutchinson & Ross, p. 348.

- Commber, J. "AFL: Test cricketer Nash played in last Swans' premiership win", AAP Australian Sports News Wire, 23 September 2005.

- Michael Howard (7 August 2003). "Star status confirmed". Hamilton Spectator. Hamilton, VIC. Archived from the original on 21 March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- Taylor, P., "Introducing Mervyn Harvey, of Fitzroy", The Argus, Weekend Supplement, (4 February 1950), p. 8.

- Shaw, back cover.

- Anderson, J. "Sid Boxall still a Hawthorn member after 85 years", Herald Sun, 27 March 2010.

- Illingworth, p. 203.

- Flanagan, p. 71.: "He'd played footy with the City club when Laurie Nash and Roy Cazaly were there and had ridden second in the island's biggest road race on a borrowed bike."

References

- Atkinson, G. (1982) Everything you ever wanted to know about Australian rules football but couldn't be bothered asking, The Five Mile Press: Melbourne. ISBN 0 86788 009 0.

- Atkinson, G. (1996). The Complete Book of AFL Finals. Melbourne: The Five Mile Press. ISBN 1-875971-47-5.

- Bradman, Don (1988). The Bradman Albums. London: MacDonald. ISBN 0-356-15411-4.

- Bradman, Don (1994). Farewell to Cricket. Sydney: Editions Tom Thompson. ISBN 1-875892-01-X.

- Clark, Manning (1990). The quest for grace. Melbourne: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-83034-3.

- Collins, B. (2008). The Red Fox: The Biography of Norm Smith: Legendary Melbourne Coach. Melbourne: Slattery Media Group. ISBN 0-9803466-2-2.

- Dunstan, Keith (1988). The Paddock That Grew: The Story of the Melbourne Cricket Club (Third ed.). Sydney: Hutchinson Australia. ISBN 0-09-169170-2.

- Fiddian, Marc (1996). Goals, Goals, Goals. Pakenham: South Eastern Independent Newspapers. ISBN 1-875475-11-7.

- Fiddian, Marc (2004). Swan Lake Spectacular: how South Melbourne won the 1933 VFL Premiership. Melbourne: Hastings. ISBN 0-9757098-0-1.

- Fingleton, Jack (1984). Cricket Crisis: Bodyline and Other Lines. London: Pavilion Books. ISBN 0-907516-68-8.

- Flanagan, Martin (1993). Going Away. Melbourne: McPhee Gribble. ISBN 0-86914-292-5.

- Frith, David (2002). Bodyline Autopsy. Sydney: ABC Books. ISBN 0-7333-1172-5.

- Hobbs, G. & Palmer, S. (1977). Football's 50 Greatest (In the Past 50 Years). Victoria: Bradford Usher & Associates, Pty. Ltd. ISBN 0-909186-00-6.

- Holmesby, Russell & Main, Jim (2002). The Encyclopedia of AFL Footballers: every AFL/VFL player since 1897 (4th ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Crown Content. ISBN 1-74095-001-1.

- Hutchinson, Garry (1983). The Great Australian Book of Football Stories. Melbourne: Currey O'Neil. ISBN 0-85902-153-X.

- Hutchinson, G. & Ross, J. (managing editors) (1998). The Clubs. Melbourne: Viking. ISBN 0-670-87858-8.

- Illingworth, Shane (2008). Filthy Rat. Fremantle: Fontaine Press. ISBN 978-0-9804170-4-3.

- Main, Jim (2006). When It Matters Most. Melbourne: Bas Publishing. ISBN 1-920910-68-9.

- Main, Jim (2009). In the Blood. Melbourne: Bas Publishing. ISBN 978-1-921496-01-1.

- Page, Roger (1957). A History of Tasmanian Cricket. Hobart: L.G. Shea.

- Perry, Roland (1995). The Don: A Biography. Sydney: Ironbark. ISBN 0-330-36099-X.

- Perry, Roland (2010). The Changi Brownlow. Sydney: Hachette. ISBN 978-0-7336-2464-3.

- Piesse, Ken (1993). The Complete Guide to Australian Football. Sydney: Ironbark. ISBN 0-7251-0703-0.

- Piesse, Ken (2003). Cricket's Colosseum. South Yarra: Hardie Grant Books. ISBN 978-1-74066-064-8.

- Pollard, Jack (1988). Australian Cricket: The Game and its Players. Sydney: Angus & Robertson Publishers. ISBN 0-207-15269-1.

- Priestley, Susan (1995). South Melbourne: A History. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84649-1.

- Richardson, Victor (1968). The Vic Richardson Story. London: Angus & Robertson.

- Rodgers, Stephen (1992). Every Game Ever Played. Melbourne: Viking O'Neil. ISBN 0-670-90526-7.

- Shaw, Ian (2006). The Bloodbath. Melbourne: Scribe. ISBN 1-920769-97-8.

- Smith, Rick (1985). Prominent Tasmanian Cricketers. Launceston: Foot & Playsted. ISBN 0-9599873-5-5.

- Tasmanian Sporting Hall of Fame (2008), Department of Sport and Recreation, Hobart.

- Wallish, E. A. (1998). The Great Laurie Nash. Melbourne: Ryan Publishing. ISBN 0-9587059-6-8.

- Whimpress, Bernard (2004). Chuckers: A history of throwing in Australian cricket. Adelaide: Elvis Press. ISBN 0-9756746-1-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Laurie Nash. |