Born to Kill (1947 film)

Born to Kill (released in the U.K. as Lady of Deceit and in Australia as Deadlier Than the Male) is a 1947 American film noir co-starring Lawrence Tierney, Claire Trevor and Walter Slezak, with Esther Howard, Elisha Cook Jr., and Audrey Long in supporting roles. Directed by Robert Wise for RKO Pictures, the feature was the first film noir production by Wise, whose later films in the genre include The Set-Up (1949) and The Captive City (1952).[1]

| Born To Kill | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Theatrical release poster by William Rose | |

| Directed by | Robert Wise |

| Produced by | Herman Schlom |

| Screenplay by | Eve Greene Richard Macaulay |

| Based on | Deadlier than the Male 1943 novel by James Gunn |

| Starring | Lawrence Tierney Claire Trevor Walter Slezak Phillip Terry Audrey Long |

| Music by | Paul Sawtell |

| Cinematography | Robert De Grasse |

| Edited by | Les Millbrook |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures Mist Entertainment |

Release date | May 3, 1947[1] |

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Plot

The film opens in Reno, Nevada, where San Francisco socialite Helen Brent (Claire Trevor) has just obtained her divorce decree at the local courthouse.

To kill time waiting for a morning train she goes to a casino that evening. At the craps table she makes eye contact with a man, Sam Wilde (Lawrence Tierney), who, though she does not know him,has been vividly described to her as physically imposing, extremely masculine, and potentially violent.

Helen is greeted there by Laury Palmer (Isabel Jewell), a young woman who lives next to the boarding house where Helen has been staying while awaiting her divorce. Laury has recently taken up with Sam, but has accepted a date with a former flame, Danny, specifically to make Sam jealous. Even though Sam does not outwardly react, her flaunting appearance there with the small, wiry tough paramour clearly irritates him.

Sam, an ex-boxer and former prison inmate prone to seizures of violence, cannot tolerate anyone "cutting in on him". Unknown to the audience he goes to Laury’s house, where he lies in wait in the darkness to run his rival off.

Upon being confronted by the obviously spoiling hulk, Danny tries to shrug it off, says Laury is not worth fighting over, that there is plenty of her to go around - all of which only further infuriates the seething Sam. Danny pulls a switchblade, Sam takes it away from him, then, completely losing control, violently bludgeons him to death. When Laury investigates the commotion she receives the same reflexive fate.

Later, heading to her boarding house, Helen happens upon Laury's little dog, which had spooked at the fighting and fled. Putting him in the home she discovers the two bodies. Helen starts to call the police but reconsiders getting involved; instead she calls to enquire about late trains to San Francisco. Sam returns to a room, and bed, he shares with his longtime pal and seeming partner Martin (Elisha Cook, Jr.), and tells him what he did. After a brief and weary reproof, Mart immediately gets Sam packing for the train, but stays behind to monitor the investigation sure to follow. To avoid Sam showing his face to a local, Mart tells him to buy his ticket aboard the train.

Helen has already purchased hers and is waiting when Sam appears. When they board the porter advises them the car is full. Sam bullies their way into the adjacent club car, telling the porter he is re-opening it, where he and Helen spend the ride sizing each other up.

Beneath an affectation of elegance and reserve, Helen reveals telltales of evident low birth; she is instantly attracted to Sam's earthy self-confidence and aggressive manner. Though she is engaged to a steel scion, Fred (Phillip Terry), she intimates that she wants to remain in touch with Sam, even recommends a favored hotel for him. Instead of keeping things in the shadows, Sam shortly arrives unannounced at the mansion where she lives with her wealthy sister, Georgia Staples (Audrey Long), heiress to a newspaper publishing fortune. Fred is there, and confounded by the stranger's appearance. Helen spins some quick lies to cover both Sam’s and her tracks.

As soon as Sam learns from Helen that kshe is merely a penniless foster sister living on Georgia's charity, he immediately shifts his attention to the innocent and insecure younger woman. After a whirlwind romance, they marry. Helen is hurt, but immediately receptive to Sam's overture of an affair.

Meanwhile Laury's best friend, Mrs. Kraft (Esther Howard), owner of the boardinghouse where Helen had stayed, has hired a private investigator, Albert Arnett (Walter Slezak), to find her killer. Shrewd but unscrupulous, he is both greedy and penniless, seemingly unsuccessful at exploiting playing both sides of the law in his work.

When Mart travels to San Francisco for Sam's wedding, Arnett follows him, then weasels himself into the Staples’ home during the reception. Raising suspicion with his persistent questioning of the staff, he is confronted by Helen. He refuses to reveal his client, but intimates to her that Sam is responsible for the Reno murders. Still wounded by Sam's betrayal, she returns the "favor" by offering some valuable but minor information about Sam and Mart to Arnett. Whose side she is on begins to cloud over....

Sam later overhears Helen making a call to Arnett and, ever paranoiac, begins to suspect she is plotting against him. Instead she is seeking to bribe the snoop to drop his investigation. He asks for an enormous amount, more than she can raise on her own. She knows she will have to get it from Fred. When she gets home, Sam confronts her. She professes loyalty. Mart overhears who hired Arnett, and, following instructions from Sam, arranges an isolated late-night rendezvous with Mrs. Kraft to eliminate her.

Before Mart leaves for the sand dunes he briefly visits Helen in her bedroom to helpfully suggest that she should end her affair with Sam. Sam sees Mart leaving and misconstrues. Before Mart can murder Mrs. Kraft Sam appears, accuses him of dallying with Helen, and, fixated, slays him, allowing Mrs. Kraft to escape.

Before Helen can lean on her fiancé Fred for the bribe money he accuses her of coldness since Sam arrived, and, in spite of her pleas, calls off their engagement. Arnett phones to tell Helen that Mrs. Kraft has been scared off, but that he is still demanding the $15,000 to keep quiet - adding ominously at the now-cornered Helen's refusal that the police will be at Georgia's house in an hour if she fails to pay.

Trying to keep everything from caving in on her, Helen confesses all to Georgia, who accuses her of making the story up, including Sam's ardor for her. Outraged, Georgia tells her she is through with her, and that she will never given Helen another dime. Helen then invites Sam into the room, who, unaware of Georgia's presence, passionately kisses Helen and announces they are fleeing together. Georgia breaks down, and Helen demands he kill her.

Before he can the police arrive. In the mayhem Sam believes it was Helen who had called them, and turns his wrath on her. She is gravely wounded by a pistol shot from him before Sam is dropped by several rounds from the officers. A morning newspaper headline confirms she dies.

Cut to Arnett, travel bag in hand in downtown San Francisco, headed back to Reno. Laury is dead. So are Mart, Sam, and Helen. Once again Arnett has overplayed his hand and outwitted himself of another payday. As he is prone to, he quotes from the Bible: "'The way of the transgressor is hard" (Proverbs 13:15), adding "More's the pity, more's the pity." It is unclear if he is referring to the deceased or himself.

Cast

- Claire Trevor as Helen Brent

- Lawrence Tierney as Sam Wilde

- Walter Slezak as Albert Arnett

- Phillip Terry as Fred Grover

- Audrey Long as Georgia Staples

- Elisha Cook Jr. as Marty Waterman

- Isabel Jewell as Laury Palmer

- Esther Howard as Mrs. Kraft

- Tony Barrett as Danny

Production

Pre-production on the film began in early February 1945, more than two years before its release. Thalia Bell of Motion Picture Daily and Irving Spear for Boxoffice reported then that RKO had hired author Steve Fisher to begin writing the screenplay for James Gunn's 1943 novel Deadlier Than the Male.[2][3] By April, however, the studio had replaced Fisher and enlisted freelance screenwriter Eve Greene and later Richard Macaulay to compose the script as a team and to manage its editing through production.[4][5]

Cast selections began in August 1945 with Lawrence Tierney being RKO's first choice due to his rising popularity after his powerful performance in Metro Pictures' Dillinger, which had been released four months earlier.[6] After announcing the casting of Tierney in August, film-industry publications in September and October reported that Tallulah Bankhead was RKO's top pick for the role of Helen Brent, but the actress was unavailable. According to the Film Bulletin the "timing was bad for Miss Bankhead" to join the project, so the part went to Claire Trevor, whose work the previous year in RKO's Murder, My Sweet had impressed studio executives.[7] Trevor in January 1946 signed the contract to co-star in the "psychological mystery" Deadlier Than the Male, which continued to be the working title for the production, as well as the title used later in the year in a series of official release charts.[8] RKO would not officially change the title to Born to Kill for domestic release until December 1946.

Regular news notices document that filming of the production began on May 6, 1946, with exterior scenes being shot first on location at El Segundo Beach, situated about 25 miles southwest of Hollywood.[9] Additional location work was done in San Francisco as filming continued into the latter half of June. As early as July, it was reported that the film was ready to be scheduled for release.[10]< Those notices proved to be premature, for problems evidently arose generating a satisfactory final cut of the film. These persisted into October 1946, when RKO announced that scheduled November 7 previews of "Deadlier Than the Male" at a national trade show and at exchange centers were being postponed.[11] In updating the status of the film, the Hollywood news journal Box Office Digest revealed that the picture was still being edited in October and was on a list of productions identified to be on RKO's "Back Log In Cutting Room".[12] A general release date of November 10, 1946 published earlier for the film was postponed as well.[13]

Post-production problems persisted right up to the final weeks prior to the film's distribution to theaters.[14]

Reception in 1947

At the time of its release in 1947, RKO's production was panned by Bosley Crowther, film critic for The New York Times, who called it "a smeary tabloid fable" and "an hour and a half of ostentatious vice." His review concluded: "Surely, discriminating people are not likely to be attracted to this film. But it is precisely because it is designed to pander to the lower levels of taste that it is reprehensible."[15] Cecelia Ager of PM, another New York newspaper, was equally blunt in expressing her utter contempt. Portions of her assessment are quoted in the May 26, 1947 issue of the Independent Exhibitors Bulletin:

"As unsavory and untalented an exhibition of deliberate sensation-pandering as ever sullied a movie screen. RKO made it, the Johnson office [in Hollywood] sanctioned it, the Palace is now playing it. It muddles them all with dishonor...Were Born to Kill merely a third rate picture hoping nevertheless to entertain, it could be passed by with a sigh. But it is third rate aiming—and with a blunderbuss—to shock, and so it provokes shudders, and not of fear.[16]

Irving Kaplan, the reviewer for the trade journal Motion Picture Daily, found "weaknesses in several departments" of "the heavy-handed melodrama", although his appraisal of the film was far less severe.[17] Kaplan focused his attention on the performances of the "tough and ruthless" Tierney and the "captivating and calculating" Trevor:

The picture itself is one of those affairs which winds up with five corpses...Portrayals generally betray a tendency toward over-acting and grotesque emphasis, perhaps to achieve over-all melodrama, while the dialogue, in spots, appears forced and weighted with flourishes.[17]

After previewing the picture two weeks prior to its release, the trade paper The Film Daily cautioned theater owners about the "homicidal drama", describing it as "a sexy, suggestive yarn of crime with punishment, strictly for the adult trade."[18] Other reviewers in 1947 also recognized the "yarn" as adult fare, but some still commended various elements of the film. William R. Weaver, the critic for the Motion Picture Herald, watched a final cut of Born to Kill in mid-April at RKO and rated it "Good".[19] He found the film's overall look "painstaking and polished" and Robert Wise's direction successful in maintaining "a steady pace".[19] Weaver did, though, find fault with what he viewed as a distinct imbalance between the motives and actions portrayed in the story. "Produced for melodrama fans," he noted, "[the film] contains enough killing for anybody, but furnishes less than adequate reasons for it."[19]

Adverse publicity and efforts to ban the film

In the weeks before and after the film's release, RKO faced two significant public-relations problems in promoting and distributing Born to Kill: widespread news coverage of the ongoing turmoil in Lawrence Tierney's personal life and actions by some state and local authorities to ban the film's presentation within their jurisdictions.

On May 2, 1947—the day before the film's official release—newspapers across the country were reporting yet another arrest of Tierney for his involvement in a "drunken brawl" and for violating probation on an earlier conviction for public drunkenness.[20][21] Other newspapers as far from Hollywood as Baltimore, Hartford, Atlanta, and Austin picked up the story, one adding that the actor had already been spending his weekends in a Los Angeles jail as punishment for three earlier convictions for public intoxication.[22] [23]

Tierney's frequent off-screen troubles with law enforcement also attracted greater scrutiny of his screen projects by state film-review boards and local censors, who began advocating banning Born to Kill in their communities.

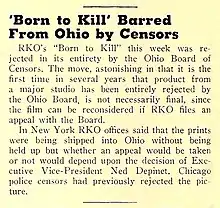

Among other publications, The Film Daily in its April 8 issue reports that Ohio's board of censors had rejected the film and banned it from state theaters.[24][25] The same news item added that Chicago's police censor board had "declined to pass" the motion picture.[24] The trade paper then reported in subsequent issues that censors in Tennessee had "cracked down" on films they deemed unacceptable and had also banned all presentations of Born to Kill in theaters in Memphis or anywhere else in Shelby County.[26] Then, in mid-May, The Motion Picture Herald disclosed that the National Legion of Decency had not condemned the film outright for its depictions of violence, although the Catholic organization had rated it "Class-B" or "objectionable in part, because it 'reflects the acceptability of divorce.'"[27]

Box office and the film's effect on future RKO productions

In the weeks leading up to the film's release, some industry publications predicted that the crime drama would be "a strong draw at the box-office".[17][28] The controversies surrounding Born to Kill, however, forced Dore Schary, RKO's executive vice-president in charge of production, to distance the company publicly from the film just days after its release. Schary in assorted interviews with reporters in early May insisted, "As a result of unfavorable reaction to 'Born to Kill', RKO will cut down on the arbitrary use of violence in its films."[29] The Hollywood executive at a motion-picture conference in New York City on May 5 was even more emphatic in his statements about production changes, vowing that "gangster pictures" such as "'Born to Kill' will no longer be produced by RKO Radio".[30][31] RKO ended up reporting a net loss of $243,000 on the production after the film's run.[17][28]

Barred from re-release by MPA

Negative reviews and unfavorable public reactions to Born to Kill and to another 1947 release, Shoot to Kill, prompted the Motion Picture Association (MPA) before the end of the year to revise its Production Code to strengthen restrictions relating to the content of crime-related films.[32] Additions were also made to the Code's guidelines under Section XI for judging and rejecting unacceptable titles given to studio productions.[33] Following a meeting of its board of directors in New York City on December 3, 1947, the MPA announced to the press that its members had voted unanimously to bar 14 "'objectionable and unsuitable'" films released between 1928 and 1947 from ever being reissued to theaters, including Born to Kill.[32][34] The association also approved the immediate deletion from its official title registry more than two dozen films with names deemed "salacious or indecent".[32] The day after the New York meeting, the Los Angeles Times summarized the board's decisions in a front-page story headlined "Film Heads Vote Ban On Gangster Pictures" and reported that the American film industry was ceasing the "distribution of new and old pictures glorifying gangster names or criminal practices".[35]

Film showcased in murder trial, 1948

Although Born to Kill faced multiple problems in 1947 with regard to its reception and distribution, RKO's production had to cope with even worse publicity in 1948, most notably with news coverage of the film's alleged connections to a homicide in Illinois. The case involved 12-year-old Howard Lang, who was charged with using a switchblade and a heavy "chunk of concrete" to kill a seven-year-old boy in Thatcher Woods outside Chicago in October 1947.[36] At the time, Lang was the youngest person ever to be arrested and formally tried for murder in that city.[37] The boy's initial trial, which drew widespread media attention, occurred in February 1948.[36] Lang was convicted of the crime, and on April 20 he was sentenced to 22 years in the state penitentiary.[38]

As part of Lang's overall defense and during the successful appeal of his conviction, his lawyers informed the court that their client had seen Born to Kill less than three weeks prior to the homicide.[39] The attorneys insisted that the violent, morally destructive aspects of the film "had affected the boy because of his emotional instability", impairing his judgement and fostering in him a form of temporary insanity.[40] They petitioned the presiding judge to view the film himself so he could appreciate the substance of their allegation that the "gangster" film was a contributing factor in the crime.[39] In the media's ongoing updates on the murder case, newspapers reported that allegation in articles with titles such as "Movie Blamed", "'Born to Kill' Movie Cited In Mitigation For Boy Slayer Lang", and "Court Refuses Plea of Lang Attorney To View 'Killer' Movie".[41]

Less than a year after Lang's initial sentencing, the Illinois Supreme Court overturned his conviction on the grounds that the boy was too young to understand his actions.[42] Lang was then acquitted of the murder in a second trial held in Chicago. The end of the case, however, did not erase the additional negative attention that the trial had focused on Born to Kill and on RKO Pictures itself. In acquitting Lang in April 1949, Judge John A. Sbarbaro recommended the enactment of several new laws to help prevent such ghastly crimes by children, two of those recommendations being to restrict the content of comic books and "to censor movies to the extent of holding theater managers liable for exhibiting 'harmful pictures'".[43]

Modern assessments of the film

Distanced by time and desensitized by contemporary standards, modern film critics find Born to Kill something of a harmless guilty pleasure. In his 2003 reference Film Noir Guide: 745 Films of the Classic Era, 1940-1959, Michael Keaney describes Born to Kill as compelling despite its "hard-to-swallow plot".[44] "This one is all Tierney", Keaney states. "He's outstanding as one of the most violently disturbed psychos in all of film noir, giving even Robert Ryan in Crossfire a run for his money."[44]

Reviewing the film in 2006 for Slant Magazine, critic Fernando F. Croce focuses on the production's director rather than on Tierney:

The usually meek Robert Wise trades his chameleonic tastefulness for full-on, jazzy misanthropy in this nasty melodrama ... Wise swims in the genre's amorality, scoring a kitchen brawl to big-band radio tunes, terrorizing a soused matron at a nocturnal beach skirmish, and leaving the last word to Walter Slezak's jovially corrupt detective.[45]

In 2009, writing for Film Monthly, critic Robert Weston also focused his attention on Wise's directorial work:

This was the first and the nastiest of the noirs directed by Robert Wise ... Wise came to the genre with a background in the Val Lewton horror team and the expressionistic films of Orson Welles, so he was the right tool for the job when it came to film noir ... As the title suggests, Born to Kill is a film about the grimmest corners of the human condition, the wicked place where sex, corruption and violence join hands and rumba round in darkness.[46]

References

- "Born to Kill (1947)", catalog, American Film Institute (AFI), Los Angeles, California. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Bell, Thalia. "Hollywood", Motion Picture Daily, February 6, 1945, p. 9. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- Spear, Irving. News item under "Clarence Brown Set to Produce 'Guardian Angel' for Metro", Boxoffice (Kansas City, Missouri), February 10, 1945, p. 36. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "26 Writers at RKO Busy on Scripts of 20 Productions", The Showmen's Trade Review, April 28, 1945, p. 68. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 17, 1945.

- "Deadlier Than the Male", Boxoffice Barometer (a supplement published by Boxoffice), November 1946, p. 196. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "Riding Herd on the Studio News Range", The Film Daily, August 29, 1945, p. 8. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "RKO-RADIO", The Film Bulletin, October 15, 1945, p. 26. I.A. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "RKO Inks Claire Trevor", Variety (New York, N.Y.), January 30, 1946, p. 8; "Production Notes From The Studios", Showmen's Trade Review, February 2, 1946, p. 29. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- "RKO Sets Two Films", Showmen's Trade Review, May 4, 1946, p. 42; "RKO Busiest Lot in Town", Showmen's Trade Review, May 25, 1946, p. 38. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- "Ready for Release Dates", The Film Daily, July 3, 1946, p. 8. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "RKO Tradeshow Off", Motion Picture Daily, October 28, 1946, p. 3. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 16, 2030.

- "RKO Pictures / Back Log In Cutting Room", Box Office Digest (Hollywood, California), October 19, 1946, p. 18. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "THE RELEASE CHART / Deadlier Than the Male...", "Product Digest Section" of Motion Picture Herald, October 19, 1946, p. 3266. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "RKO-RADIO Release Chart / Born to Kill...", Film Bulletin, February 17, 1947, p. 31. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- Crowther, Bosley (May 1, 1947). ""The Screen" (review)". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- "'Born to Kill': RKO-Radio", Independent Exhibitors Bulletin, May 26, 1947, p. 27. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- Kaplan, Irving. "Reviews: 'Born to Kill'", Motion Picture Daily (New York, N.Y.), April 21, 1947, p. 7. Internet Archive, San Francisco, California. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- "Reviews: 'Born to Kill'", The Film Daily (New York, N.Y.), April 17, 1947, p. 7. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- Weaver, William R. "Born to Kill: RKO Radio—Murder Melodrama", Motion Picture Herald (New York City), April 19, 1947, p. 3585. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- "Tierney Fights Brother; Gets 90 Days In Jail", Los Angeles Times, May 2, 1947, p. 2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers, Ann Arbor, Michigan; subscription access through the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.

- "'Dillinger' Tierney In Trouble Again", The Atlanta Constitution, May 2, 1947, p. 1. ProQuest.

- "Actor Jailed After Fight", The Austin Statesman (Austin, Texas), May 2, 1947, p. 24. ProQuest.

- "Tierney Fights Brother; Gets 90 Days In Jail", Los Angeles Times, May 2, 1947, p. 2; "Actor Tierney Must Sleep on Jail Floor", Los Angeles Times, May 3, 1947, p. 3; "Lawrence Tierney Fined $25 For Intoxication", The Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), May 10, 1947, p. 11; "Tierney Draws New $25 Fine", Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1947, p. A3; "Board Grants Parole To Film Actor Tierney", The Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut), June 18, 1947, p. 2; "Bad Man Tierney Granted Freedom", The Atlanta Constitution, June 19, 1947, p. 4. ProQuest.

- "Ohio's Censors Reject RKO's 'Born to Kill'", The Film Daily (New York, N.Y.), April 19, 1947, p. 4. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- "'Born to Kill' Barred From Ohio by Censors", Showmen's Trade Review, April 12, 1947, p. 8.

- "'Born to Kill' Joins Memphis Banned Pix", The Film Daily, April 25, 1947, pp. 1, 3. Internet Archive; "Memphis Bans Another Film", The New York Times, April 25, 1947, p. 29. ProQuest.

- "Legion of Decency Reviews Five New Productions", The Motion Picture Herald, May 17, 1947, p. 44. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- Jewell, Richard B. (2016) Slow Fade to Black: The Decline of RKO Radio Pictures, Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520289673

- "Good Story Material Scarce", Motion Picture Herald, May 10, 1947, p. 19. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- "Films of Violence Abandoned: Schary", Motion Picture Daily (New York, N.Y.), May 6, 1947, pp. 1, 6. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- "Reaction to 'Born to Kill' Will Affect New RKO Product—Schary", Showmen's Trade Review, May 10, 1947. pp. 5, 18.

- "MPA Strengthens Code on Titles And Crime Films", Motion Picture Herald, December 6, 1947, p. 20.

- "Code Changes Hit Reissue of 14 Films", The Motion Picture Daily, December 5, 1947, pp. 1, 4. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- "Movie Makers Bar Glorifying Crime", The New York Times, December 4, 1947, p. 64.

- "Film Heads Vote Ban On Gangster Pictures", Los Angeles Times, December 4, 1947, p. 1.

- Murder Trial Begins For Chicago Boy Of 12", Los Angeles Times, February 17, 1948, p. 2. ProQuest.

- Cohn, Victor. "Howard Lang Trial Like a 'Bad Dream'", The Minneapolis Morning Tribune, February 20, 1948, p. 11. ProQuest.

- "Lang Weeps Over 22 Year Term", Chicago Daily Tribune, April 21, 1948, p. 1. ProQuest.

- "Bans Film From Court", Boxoffice, April 6, 1948, p. 64. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- "'Born to Kill' Movie Cited In Mitigation For Boy Slayer Lang", Chicago Daily Tribune, March 20, 1948, p. 3. ProQuest.

- "Movie Blamed", The Minneapolis Morning Tribune (Minnesota), March 20, 1948, p. 10; "'Born to Kill' Movie Cited In Mitigation For Boy Slayer Lang", Chicago Daily Tribune, March 20, 1948, p. 3; "Court Refuses Plea of Lang Attorney To View 'Killer' Movie", Chicago Daily Tribune, March 26, 1947, p. 17. ProQuest.

- "Illinois Supreme Court", news item, The St. Petersburg Times (Florida), January 20, 1949, p. 1.

- "LANG ACQUITTED BY JUDGE IN 2D MURDER TRIAL: State Plans New Move to Confine Him", Chicago Daily Tribune, April 27, 1949. p. 7.

- Kearney, Michael. Film Noir Guide: 745 Films of the Classic Era, 1940-1959. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003, pp. 63-64.

- Croce, Fernando F. (2006) "Born to Kill (Robert Wise, 1947)" (review) Slant Magazine. Last accessed: January 19, 2019.

- Weston, Robert (October 2, 2001) "Born to Kill (1947)" (review) Film Monthly. Last accessed: December 1, 2009.