Brodmann area 22

Brodmann area 22 is a Brodmann's area that is cytoarchitecturally located in the posterior superior temporal gyrus of the brain.[1] In the left cerebral hemisphere, it is one portion of Wernicke's area.[2] The left hemisphere helps with generation and understanding of individual words. On the right side of the brain, it helps to discriminate pitch and sound intensity, both of which are necessary to perceive melody and prosody. Wernicke's area is active in processing language and consists of the left Brodmann area 22 and Brodmann area 40, the supramarginal gyrus.

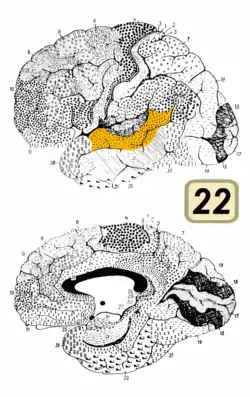

| Brodmann area 22 | |

|---|---|

Brodmann area 22 (orange) | |

Coronal section of the human brain. BA22 is shown in yellow. | |

| Identifiers | |

| NeuroNames | 1017 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1753 |

| FMA | 68619 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

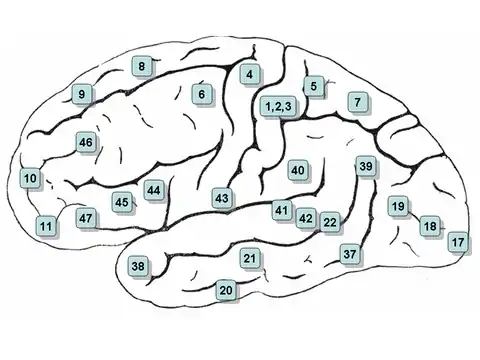

It is bounded rostrally by Brodmann area 38, medially by Brodmann area 42, ventrocaudally by Brodmann area 21, and dorsocaudally by Brodmann area 40, and Brodmann area 39. These cortical regions surround the lower left posterior Sylvian fissure.[1]

History of Brodmann Area

The Brodmann areas originated in 1909 by scientist Korbinian Brodmann after publishing the first cytoarchitectonic map of a human brain. Cytoarchitecture is a method used to divide the cerebral cortex of the brain into Brodmann areas. The cytoarchitectonic map separated the cerebral cortex into 43 areas as a way to study and understand the structure of the human brain.[3] Brodmann developed this idea of using a parcellation approach for areas of the brain by studying cell distribution in grey matter, structure of the cortical layers and neuron density.[3] This idea was founded by examining the human brain compared to human and non-human primates. The human brain areas are labelled 1 through 52, however not all are shown on his illustration. Brodmann found gaps in specific areas that are not distinguishable in the human brain yet they appear in other species. Brodmann labelled these unseen areas as 12-16 and 48-51 on the human brain map. [3] These numbers are used for examining the functional activity in the different areas of the brain. The Brodmann areas that are relevant to language include Broca's area (BA 44/45) and Wernicke's area (BA 42/22), where Broca's area is responsible for language production and Wernicke's area is responsible for language comprehension. [4]

Language

Brodmann area 22 (BA 22) combined with Brodmann area 42 (BA 42) form Wernicke’s area in the superior temporal gyrus in the temporal lobe. Using cytoarchitectonics, BA 22 is located in the superior temporal gyrus which separates it from the primary and secondary auditory cortex.[4] BA 22 is connected with nonverbal sound processing in the right hemisphere of the brain associated with activation in the auditory cortex. More functions associated with language in Brodmann area 22 include producing sentences, semantic processing, and processing of complex sounds.[5] This area of the human brain supports lexical semantic processing and is responsible for language comprehension and production. Wernicke's area is shown to support lexical-semantics because lesions to this area result in difficulties displaying word selection during production of language.[4]

Wernicke's Aphasia

Because Wernicke’s area supports language comprehension in the temporal lobe, lesions to the left auditory cortex, specifically in BA 22, results in Wernicke’s aphasia. Wernicke’s aphasia, also known as receptive aphasia, is a language disorder characterized as having difficulty comprehending language. This disorder varies in outcomes based on severity and localization of the brain damage, which is mostly commonly due to having a stroke.[5] Patients diagnosed with Wernicke's aphasia are shown to have normal intonation and rate of speech, however have difficulty understanding different words of a language. Many individuals have poor awareness when making errors in speech, but are typically able to produce normal sentence structures when speaking. [6] These sentences produced by patients with Wernicke's aphasia are often difficult for others to understand because of the problems with word selection and comprehension. These difficulties are shown at a lexical level, for example patients often struggle with naming figures due to accessing words from the lexicon.[4]

Methodology

Methods used to understand functional activity in BA 22 consists mainly of Functional magnetic resonance imaging. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a neuroimaging technique used to understand how language is processed in the BA 22. [7] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a technique used to study volume of grey matter and white matter in Brodmann area 22 to find deficits in the structural volume.[8]

Parcellations

Brodmann areas are based on cytoarchitectonic parcellation using numbering associated with locations in the brain to illustrate functional activity. BA 22 is separated from the primary and secondary auditory cortex by using cytoarchitectonic parcellation.[4] Connectivity-based parcellations in BA 22 can be broken into three subparts: posterior, middle, and anterior subparts of the superior temporal gyrus. Using connectivity-based parcellations involves connections between white fibers to different areas in the brain.[4] Cytoarchitectonic parecellations and connectivity-based parcellations are two ways of breaking the brain down to the structure and the connection fibers of Brodmann Area 22.

References

- Binder, JR (15 December 2015). "The Wernicke area: Modern evidence and a reinterpretation". Neurology. 85 (24): 2170–5. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002219. PMC 4691684. PMID 26567270.

- Binder, JR (15 December 2015). "The Wernicke area: Modern evidence and a reinterpretation". Neurology. 85 (24): 2170–5. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002219. PMC 4691684. PMID 26567270.

- Amunts, Katrin; Zilles, Karl (2010). "Centenary of Brodmann's Map- conception and fate" (PDF). Nature Reviews. 11 (2): 139–45. doi:10.1038/nrn2776. PMID 20046193. S2CID 5278040. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Friederici, Angela D. (2017). Language in Our Brain: the origins of a uniquely human capacity. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 6–11, 103–210. ISBN 9780262036924.

- Trans Cranial Technologies ldt. (2012). "Cortical Functions" (PDF). 1: 36–37. Retrieved 19 October 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Acharya, Aninda B. (2019). StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- Ardila, Alfredo; Bernal, Byron; Rosselli, Monica (2016). "How Localized are Language Brain Areas? A Review of Brodmann Areas Involvement in Oral Language". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 31 (1): 112–122. doi:10.1093/arclin/acv081. PMID 26663825.

- Mitelman, Serge A.; Shihabuddin, Lina; Brickman, Adam M.; Hazlett, Erin A.; Buchsbaum, Monte S. (2003). "MRI Assessment of Gray and White Matter Distribution in Brodmann's Ares of the Cortex in Patients With Schizophrenia With Good and Poor Outcomes". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (12): 2154–2166. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2154. PMID 14638586.

Gallery

Inside and outside of lateral sulcus. BA22 is shown in orange.

Inside and outside of lateral sulcus. BA22 is shown in orange.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brodmann area 22. |