Brummagem

Brummagem (and historically also Bromichan, Bremicham and many similar variants, all essentially "Bromwich-ham") is the local name for the city of Birmingham, England, and the dialect associated with it. It gave rise to the terms Brum (a shortened version of Brummagem) and Brummie (applied to inhabitants of the city, their accent and dialect).

"Brummagem" and "Brummagem ware" are also terms for cheap and shoddy imitations, in particular when referring to mass-produced goods. This use is archaic in the UK, but persists in some specialist areas in the US and Australia.

History

The word appeared in the Middle Ages as a variant on the older and coexisting form of Birmingham (spelled Bermingeham in Domesday Book), and was in widespread use by the time of the Civil War.

17th century

The term's pejorative use appears to have originated with the city's brief 17th-century reputation for counterfeited groats.

Birmingham's expanding metal industries included the manufacture of weapons. In 1636, one Benjamin Stone petitioned that a large number of swords, which he claimed to have made, should be purchased for the use in the King's service; but in 1637, the Worshipful Company of Cutlers, in London, countered this by stating that these were actually "bromedgham blades" and foreign blades, and that the former "are no way serviceable or fit for his Majesty's store".[1][2][3] John F. Hayward,[4] an experienced historian on swords, suggests that London's snobbery towards these blades at that time "may have been due to" commercial rivalry; at that time London was the largest provider of weapons in Britain, and Birmingham was fast becoming a viable commercial threat to their trade.[5]

The word passed into political slang in the 1680s.[6] The Protestant supporters of the Exclusion Bill were called by their opponents Birminghams or Brummagems (a slur, in allusion to counterfeiting, implying hypocrisy). Their Tory opponents were known as anti-Birminghams or anti-Brummagems.

Around 1690 Alexander Missen, visiting Bromichan in his travels, said that "swords, heads of canes, snuff-boxes, and other fine works of steel," could be had, "cheaper and better here than even in famed Milan."

Guy Miege, in The New State of England (1691), wrote: "Bromicham is a large and well-built Town, very populous, and much resorted unto; particularly noted, few years ago, for the counterfeit Groats made here, and from hence dispersed all over the Kingdom."[7]

18th century

During the 18th century Birmingham was known by several variations of the name "Brummagem".

In 1731, an old "road-book" said that "Birmingham, Bromicham, or Bremicham, is a large town, well built and populous. The inhabitants, being mostly smiths, are very ingenious in their way, and vend vast quantities of all sorts of iron wares."

Around 1750, England's Gazetteer described Birmingham or Bromichan as "a large, well-built, and populous town, noted for the most ingenious artificers in boxes, buckles, buttons, and other iron and steel wares; wherein such multitudes of people are employed that they are sent all over Europe; and here is a continual noise of hammers, anvils, and files".

The town was renowned for its miscellany of metal and silver industries, some of whose manufacturers used cheap materials, exhibiting poor quality and design. The poorer-quality "Brummagem ware" was beginning to give the better more skilled metal workers of the town a bad name; Matthew Boulton of the Lunar Society and several toy makers and silversmiths realized this and campaigned to have the town's first assay office constructed. Great opposition came from the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths in London but royal assent was given for assay offices in both Birmingham and Sheffield on the same day. Eventually this filtered out much of the poor workmanship of silver and jewellery in Birmingham, keeping mainly the higher-quality jewellery produced, which ultimately enabled the town to become one of the most important silver manufacturing centres in the 19th century.

It is thought by some, including historian Carl Chinn, that around this time Matthew Boulton favoured "Birmingham" over "Brummagem" to avoid negative connotations.

19th century

By the 19th century Birmingham had become one of the most important players in the Industrial Revolution. Matthew Boulton had taken part in the first British trade missions to China and the city was one of the most advanced, diverse and productive manufacturing centres in the modern world. Birmingham was sometimes referred to as the "toyshop of Europe", "workshop of the world", or "city of a thousand trades". The Birmingham pen trade prospered and areas such as the Gun Quarter and Jewellery Quarter existed with high standards of production set out by institutions such as the Birmingham Proof House and Birmingham Assay Office. The Birmingham Mint also became internationally renowned for its high-quality coins, as did Cadburys for its chocolate and workers' welfare and rights.

With such a vast array of items being produced it was inevitable that not all would have been of high quality; and the advances of the industrial revolution enabled machines to mass-produce cheaper items such as buttons, toys, trinkets and costume jewellery. The poor quality of a proportion of these gave rise to a pejorative use of the word, "Brummagem ware", although such items were not exclusive to the city.

The significant button industry gave rise to the term "Brummagem button". Charles Dickens's novel The Pickwick Papers (1836) mentions it as a term for counterfeit silver coins; but Samuel Sidney's Rides on Railways (1851) refers to it as "an old-fashioned nickname for a Birmingham workman".[8]

By the late 19th century, "Brummagem" was still used as a term for Birmingham. Some people still used it as a general term for anything cheap and shoddy disguised as something better. It was used figuratively in this context to refer to moral fakery: for instance, the Times leader, 29 January 1838, reported Sir Robert Peel's slur on an opponent: "[who] knew the sort of Brummagem stuff he had to deal with, treated the pledge and him who made it with utter indifference".

One particularly negative use of the word is "brummagem screwdriver", a term for a hammer, a jibe which suggested that Brummie workers were unskilled and unsophisticated, though it was similarly applied to the French and Irish.[9]

The negative use of the word was included in several dictionaries around the world.

Carts were passing to and fro; groups of Indians squatting on their haunches were chattering together, and displaying to one another the flaring red and yellow handkerchiefs, the scarlet blankets, and muskets of the most worthless Brummagem make, for which they had been exchanging their bits of gold, while their squaws looked on with the most perfect indifference.[10]

The equipages were generally much more gorgeous than at a later period, when democracy invaded the parks, and introduced what may be termed a "brummagem society," with shabby-genteel carriages and servants.[11]

The furs, fossil ivory, sheepskins and brick tea brought by them after voyages often reaching a year and eighteen months, come, strictly enough, under the head of raw products. Still, it is the best they can bring; which cannot be said of what Europe offers in exchange – articles mostly of the class and quality succinctly described as "Brummagem".[12]

The term was not always used with negative meaning. A character in Jeffery Farnol's novel The Broad Highway (1910) comments:

"A belt, now," he suggested mournfully, "a fine leather belt wi' a steel buckle made in Brummagem as ever was, and all for a shillin'; what d'ye say to a fine belt?"[13]

and the Rev. Richard H. Barham:

He whipp'd out his oyster-knife, broad and keen

A Brummagem blade which he always bore,

To aid him to eat,

By way of a treat,

The "natives" he found on the Red Sea shore;

He whipp'd out his Brummagem blade so keen,

And he made three slits in the Buffalo's hide,

And all its contents,

Through the rents, and the vents,

Come tumbling out, – and away they all hied![14]

However, as shown by James Dobbs's song "I can't find Brummagem" (see below), it remained in use as a geographical name for the city.[15]

In the Henry James story "The Lesson of the Master" (1888), the novelist Henry St. George refers to his "beautiful fortunate home" as "brummagem" to indicate that it is worth little in comparison to what he has given up to have it; he has sacrificed his pursuit of great writing in order to live the life of a comfortable, well-off man. He expresses his regret to the story's protagonist, an aspiring young writer named Paul Overt.[16]

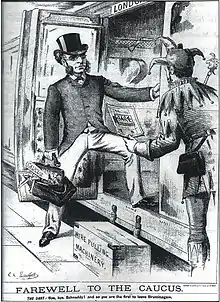

The Birmingham politician Joseph Chamberlain was nicknamed "Brummagem Joe" (affectionately or satirically, depending on the speaker). See, for instance, The Times, 6 August 1895: "'Chamberlain and his crew' dominated the city ... Mr Geard thought it was advisable to have a candidate against 'Brummagem Joe'".

There were many contradictory comments and accounts to the idea that Birmingham or Brummagem was associated with poor-quality manufacture around the 19th century. Robert Southey wrote in 1807: "Probably in no other age or country was there ever such an astonishing display of human ingenuity as may be found in Birmingham."

Modern usage

"Brummagem" remained a staple of British political and critical discourse into the early 20th century. The Times of 13 August 1901 quoted a House of Commons speech by J. G. Swift MacNeill on the subject of the Royal Titles Bill: "The initiative of the Bill ... had the 'Brummagem' brand from top to bottom. It was a mean attempt, inspired by the absurd and vulgar spirit of Imperialism, to subsidize the Crown with a parvenu title, and a tawdry gewgaw reputation".[17]

A Punch book review for December 1917 said: "But, to be honest, the others (with the exception of one quaint little comedy of a canine ghost) are but indifferent stuff, too full of snakes and hidden treasure and general tawdriness – the kind of Orientalism, in fact, that one used to associate chiefly with the Earl's Court Exhibition. Mrs. PERRIN must not mingle her genuine native goods with such Brummagem ware".

In John Galsworthy's In Chancery (1920), the second volume of his Forsyte Saga trilogy (Book II, Part II, Chapter I: The Third Generation), when responding to the question, "Do you know Crum?", Jolly Forsyte replies, "Of Merton? Only by sight. He's in that fast set too, isn't he? Rather La-di-da and Brummagem." Around this time, Birmingham's foremost criminal gang referred to themselves as the Brummagem boys.

By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, British usage had shifted toward a purely geographical and even positive sense. The Housing Design Awards 1998 said of one Birmingham project, City Heights, "this gutsy Brummagem bruiser of a building handles its landmark status with ease and assurance". In The Guardian "Notes from the touchline" sport report, 21 March 2003, journalist Frank Keating used the headline "World Cup shines with dinkum Brummagem" to praise the performance of Birmingham-born Australian cricketer Andrew Symonds.

A particular activist in reclaiming the term as a traditional name reflecting positive aspects of the city's heritage is historian Carl Chinn MBE, Professor of Community History at the University of Birmingham, who produces Brummagem Magazine.

The British poet Roy Fisher (b. 1930) uses the term in his poetry sequence, "Six Texts For a Film", in Birmingham River (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994). "Birmingham's what I think with. / It's not made for that sort of job,/ but it's what they gave me. / As a means of thinking, it's a Brummagem/ screwdriver" (lines 1–4).

US usage

In the US, the negative usage appears to have continued into the 1930s. F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1922 novel The Beautiful and Damned uses the word twice: "It was one of the type known as 'tourist' cars, a sort of brummagem Pullman ... a single patch of vivid green trees that guaranteed the brummagem umbrageousness of Riverside Drive". Gilbert Seldes, in his 1924 book The Seven Lively Arts, wrote in praise of Krazy Kat: "everything paste and brummagem has had its vogue with us; and a genuine, honest native product has gone unnoticed". It appears in two essays by H.L. Mencken from 1926: "Valentino" ("Consider the sordid comedy of his two marriages – the brummagem, star-spangled passion that invaded his very deathbed!") and "A Glance Ahead" ("It would be hard to find a country in which such brummagem serene highnesses are revered with more passionate devotion than they get in the United States."). Mencken's influence is apparent when the term appears in John Fante's 1939 novel Ask the Dust: "The church must go, it is the haven of the booboisie, of boobs and bounders and all brummagem mountebanks."

Currently US collectors of political memorabilia use "brummagem" to refer to imitations.[18] The Dictionary of Sexual Terms and Expressions by Farlex Inc., maintainers of TheFreeDictionary.com, lists several related terms such as "Brummagem buttons", tufts sewn to brassiere cups to give the appearance of larger nipples. Lemony Snicket, in his 1999 young adult novel The Reptile Room, introduces brummagem as a "rare word for 'fake'".[19]

Brummagem in song

A song, "I Can't Find Brummagem", was written by James Dobbs (1781–1837), a Midland music hall entertainer.[15]

"The Birmingham School of Business School", a song by The Fall on the 1992 album Code: Selfish, about the "creative accounting techniques" of Trevor Long, a manager of the band, includes the lyric "Brummagem School of Business School".[20]

References

- Calendar of State Papers, Domestic series, of the reign of Charles I, page 105, paragraph 47 at archive.org

- Welch, Charles History of the Cutlers' Company of London and of Minor Cutlery Crafts: From 1500 to modern times, 1923

- Hayward, John F. English Swords 1600–1650 at myArmoury.com

- Contributing Authors at myArmoury.com

- Hayward, John F. English Swords 1600–1650 at myArmoury.com

- "Brummagem, adj. and n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Miege, Guy (1691). The New State of England Under Their Majesties K. William and Q. Mary. London: Jonathan Robinson. p. 235.

- Sidney, Samuel (1851). Rides on Railways Leading to the Lake & Mountain Districts of Cumberland, North Wales, and the Dales of Derbyshire. London: William S. Orr & Co. p. 81.

- Slang Down the Ages: the historical development of slang, Jonathon Green, Kyle Cathie, 1993.

- J. Tyrwhitt Brooks, California, 1849

- Rees Howell Gronow, The Reminiscences of Captain Gronow, 1862.

- Description of a trade fair, Lippincott's Magazine, 1876.

- 'The Broad Highway'.

- 'The Ingoldsby Legends'

- Raven, Jon (1978). Victoria's Inferno: Songs of the Old Mills, Mines, Manufactories, Canals and Railways. Wolverhampton: Broadside Books. ISBN 0-9503722-3-4.

- James, Henry. The Lesson of the Master. Hoboken: Melville House Publishing, 2004: 90.

- "House of Commons: Monday, Aug. 12". The Times. 13 August 1901. p. 4.

- "Brummagem (Fakes, Reproductions, Fantasy Items, and Re-pins)". American Political Items Collectors. American Political Items Collectors. 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Snicket, Lemony (1999). The Reptile Room: A Series of Unfortunate Events, Book the Second. New York: Scholastic Inc. p. 90. ISBN 0-439-20648-0.

"My, my, my, my, my," said a voice from behind them, and the Baudelaire orphans turned to find Stephano standing there, the black suitcase with the shiny silver padlock in his hands and a look of brummagem surprise on his face. "Brummagem" is such a rare word for "fake" that even Klaus didn't know what it meant, but the children did not have to be told that Stephano was pretending to be surprised.

- "The Birmingham School of Business School: Lyrics". The Annotated Fall. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Brummagem. |

- Why Brummies Why not Birmies? Etymological article by Dr Carl Chinn

- Birmingham or Brummagem? Birmingham City Council page listing the name variants from William Hamper's 1880 booklet AN HISTORICAL CURIOSITY, by a Birmingham Resident, ONE HUNDRED AND FORTY-ONE WAYS OF SPELLING BIRMINGHAM.

- Macaulay's The History of England from the Accession of James II, Vol. 1 Origin of political slang 'Birminghams'

- Brummagem Magazine

- I can't find Brummagem at the Digital Tradition Folksong Database

- Brummagem: An APIC Project: A Handbook on Fakes, Fantasies & Repins American Political Items Collectors guide

- The Pickwick Papers at Project Gutenberg

- Rides on Railways, 1851, by Samuel Sidney at FullTextArchive.com

- The Beautiful and Damned F. Scott Fitzgerald, 1922, The University of Adelaide Library Electronic Texts Collection

- The Seven Lively Arts, Gilbert Seldes, 1924, University of Virginia Electronic texts for the Study of American Culture