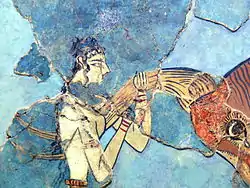

Bull-Leaping Fresco

The Bull-Leaping Fresco, as it has come to be called, is the most completely restored of several stucco panels originally sited on the upper-story portion of the east wall of the palace at Knossos in Crete. Although they were frescos, they were painted on stucco relief scenes and therefore are classified as plastic art. They were difficult to produce. The artist had to manage not only the altitude of the panel but also the simultaneous molding and painting of fresh stucco. The panels, therefore, do not represent the formative stages of the technique. In Minoan chronology, their polychrome hues – white, pale red, dark red, blue, black – exclude them from the Early Minoan (EM) and early Middle Minoan (MM) Periods. They are, in other words, instances of the "mature art" created no earlier than MM III. The flakes of the destroyed panels fell to the ground from the upper story during the destruction of the palace, probably by earthquake, in Late Minoan (LM) II. By that time the east stairwell, near which they fell, was disused, being partly ruinous.

| Bull-Leaping Fresco | |

|---|---|

| Greek: Ταυροκαθάψια (Taurokathapsia) | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Artist | Unknown |

| Year | 1450 BC |

| Type | Fresco |

| Medium | Stucco panel with scene in relief |

| Dimensions | 78.2 cm × 104.5 cm (30.8 in × 41.1 in) |

| Location | Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Heraklion, Crete |

| Owner | Hellenic Republic |

The subject is common in Minoan art, one of a number depicting the handling of bulls. Arthur Evans, Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, owner of the palace and director of excavation, presents the topic in Chapter III of his monumental work on Knossos and Minoan Civilization, Palace of Minos. There he calls the several frescos "The Taureador Frescos."[1]

Theme

Concepts of bull-leaping

Arthur Evans recognized that depictions of bulls and bull-handling had a long tradition represented by copious instances in multi-media art, not only at Knossos, and other sites on Crete, but also in the Aegean and on mainland Greece, with a tradition even more ancient in Egypt and the Middle East. At Knossos he distinguished between "bull-grappling scenes" or "'cow-boy' feats in the open" and "Circus Sports." The cowboy scenes depict the catching and handling of wild cattle, represented by animal icons very like the aurochs from which kine were domesticated. This type of cattle motif is shown on the stucco fresco in the North Entrance of the palace. Additionally, Jordan Wolfe, of Furman University, explains how the act of bull-leaping is especially significant to Minoan culture because it highlights man's dubious mastery of nature.[3]

The Circus Sports are to be contrasted to Bull-Catching. They are "a more structurally organized and ceremonial form of the sport confined, of its very nature, to a specially devised structure."[4] He goes on to conjecture, "the Palace Bull-Ring itself lay on the river flat immediately below." The Taureador Frescoes, then, are not depictions of real events in real time, but are decorative motifs on the wall above a ceremonial bull-ring. They depict a stock scene, of a conventional nature, which has come to be termed "bull-leaping." It still has no viable definition. Although it vaguely brings to mind the act of jumping over bulls, the technique and the reasons for doing that remain obscure, a century after the discovery of the frescos.

Modern attempts to recreate the leaping on modern cattle have resulted only in a number of deaths. In short, the bull is too fast, too powerful and too aggressive to allow seizure of the horns, much less the use of the energy of the neck toss for acrobatics. Moreover, that toss is a hook to the side, not a neat backward boost. The bull attempts to skewer the human with one horn, without a view toward the style of the frescos. It is possible to leap over small bulls without touching them, even as they charge, and such spectacles still practiced in France may be the ultimate source of the icon. A stationary bull might be touched or pushed on the way over, but pressing on a bull in motion would have the same effect as being sideswiped by a speeding vehicle; that is, tumbling out of control.[2]

The Taureador Frescoes are not frauds or incorrect reconstructions. The same bull-leaping scene appears in miniature in sealings and sealstones of the MM and LM periods.[5] Explanations and classifications of the figures depicted are strictly theoretical, never illustrated by real-life examples. The only certain perception is that the leaper goes over the bull in an upside-down position, whether diving from above, leaping up from below, or with or without the assistance of another human or a device such as a pole. Why he should choose to do so also is strictly theoretical, although motives may probably presumed to be similar to those of modern adolescents in France: adventure and peer status. It would have to be, certainly, a volunteer activity of some social reward.

Taurokathapsia and other classical words

Evans noted the survival of bull sports into classical times; for example, the taurokathapsia of Thessaly. The word means "laying hold of the bull," which in modern times is sometimes used for dabing of the Taureador Fresco. Evans did not use it in that way. The Thessalian taurokathapsia was performed from horseback. The Tiryns Fresco depicts a youth on the back of a bull holding its horns, an activity similar to bull-dogging. First the bull in the ring is baited by riders to exhaust him. Then a rider comes up beside him, leaps on his back, seizes the horns, and falling to one side twists the head, bringing down the tired bull. Macedonian coins depict Artemis Tauropolos, "Artemis Bullrider," mounted on a charging bull. Miletus held the Boegia, "Bull Driving," involving a bull-grappling contest.[6]

One problem with the Taureador Fresco as a taurokathapsia is its logical sequence. Depicted are three individuals, two women (one at the front, one at the back), and a male youth shown balancing on the bull.[7] Their genders are identified according to the accepted Minoan art convention of painting women with pale skin and men with dark skin. The status of the participants is identified by their clothes and jewelry. The bull evidences the Mycenaean Flying Leap, which means he is intended to be at full gallop. The artist has shown the bull's body in an elongated form with extended legs to indicate movement. His horns, however, are being firmly held by the woman in front - possibly either in preparation to leap over the bull, or while stationary. However, if the woman is holding the bull, it cannot be galloping. The boy could be interpreted as being shown in a balancing, not a tumbling, position. He holds the flanks of the bull with both hands. If he were tumbling, and if he had used the horns to get a purchase, the woman would not be now holding them. It may not show a compressed chronological sequence, as the individuals are all different. Instead, icons that are disconnected in real time and space may have been superimposed to give an overall impression of a scene familiar to the artists and their viewers, but not to today's public.

Gallery of other Minoan bull-leaping scenes

.jpg.webp) Bull-leaping on a gold signet ring

Bull-leaping on a gold signet ring_(cropped).jpg.webp) Bronze bull-leaper group in the British Museum

Bronze bull-leaper group in the British Museum.jpg.webp) Ivory bull-leaper, "Ivory Deposit" at Knossos, prob. MM IIIB, AMH.[8]

Ivory bull-leaper, "Ivory Deposit" at Knossos, prob. MM IIIB, AMH.[8] Fragment of painting on rock crystal, Knossos, 1600-1450 BC, AMH

Fragment of painting on rock crystal, Knossos, 1600-1450 BC, AMH

Notes

- Evans 1930, p. 203.

- McInerney, Jeremy (Winter 2011). "Bulls and Bull-leaping in the Minoan World" (PDF). Expedition. 53 (3): 6–13.

- ""Bull-Leaping Fresco (ca. 1450-1400 BC)" by Jordan Wolfe". scholarexchange.furman.edu. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- Evans 1930, p. 204.

- Younger, John G. (1995), "Bronze Age Representations of Aegean Bull-Games III", in Laffineur, Robert; Niemeier, Wolf-Dietrich (eds.), POLITEIA. Society and State in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 5th International Aegean Conference / 5e Rencontre égéenne internationale, University of Heidelberg, Archäologisches Institut, 10–13 April 1994 (PDF), Aegaeum 12, pp. 507–549, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016, retrieved 9 May 2012

- Evans & 1935A, pp. 45–47.

- Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective. Volume I. Wadsworth, 2010. p.72

- Hood, 119

References

- Hood, Sinclair, The Arts in Prehistoric Greece, 1978, Penguin (Penguin/Yale History of Art), ISBN 0140561420

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bull-leaping fresco (Knossos, main palace). |

- Evans, Arthur John (1930). PM. Volume III: The great transitional age in the northern and eastern sections of the Palace: the most brilliant record of Minoan art and the evidences of an advanced religion. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2012-05-08.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- —— (1935A). PM. Volume IV Part I: Emergence of outer western enceinte, with new illustrations, artistic and religious, of the Middle Minoan Phase, Chryselephantine "Lady of Sports", "Snake Room" and full story of the cult Late Minoan ceramic evolution and "Palace Style". Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2012-05-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- —— (1935B). PM. Volume IV Part II: Camp-stool Fresco, long-robed priests and beneficent genii, Chryselephantine Boy-God and ritual hair-offering, Intaglio Types, M.M. III - L. M. II, late hoards of sealings, deposits of inscribed tablets and the palace stores, Linear Script B and its mainland extension, Closing Palatial Phase, Room of Throne and final catastrophe. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2012-05-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacGillivray, Joseph Alexander. Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth. Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, 2000.

- (in Greek) C. Christopoulos (ed.), Ελληνική Τέχνη, Η Αυγή της Ελληνικής Τέχνης, Εκδοτική Αθηνών (Greek Art, The Dawn of Greek Art), (Athens 1994).