Aurochs

The aurochs (/ˈɔːrɒks/ or /ˈaʊrɒks/; pl. aurochs, or rarely aurochsen, aurochses) (Bos primigenius), also known as urus or ure, is an extinct species of large wild cattle that inhabited Asia, Europe, and North Africa. It is the ancestor of domestic cattle. The species survived in Europe until 1627, when the last recorded aurochs died in the Jaktorów Forest, Poland.

| Aurochs Temporal range: Early Pleistocene — 1627 CE | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton of a bull at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Bovinae |

| Genus: | Bos |

| Species: | †B. primigenius |

| Binomial name | |

| †Bos primigenius (Bojanus, 1827) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Wild:

domestic:

| |

| |

| Distribution of the three subspecies | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

During the Neolithic Revolution, which occurred during the early Holocene, at least two aurochs domestication events occurred: one related to the Indian subspecies, leading to zebu cattle, and the other related to the Eurasian subspecies, leading to taurine cattle. Other species of wild bovines were also domesticated, namely the wild water buffalo, gaur, wild yak, and banteng. In modern cattle, many breeds share characteristics of the aurochs, such as a dark colour in the bulls, with a light eel stripe along the back (the cows being lighter), or an aurochs-like horn shape.[2]

Taxonomy

The aurochs was variously classified as Bos primigenius, Bos taurus, or, in old sources, Bos urus. However, in 2003, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature "conserved the usage of 17 specific names based on wild species, which are predated by or contemporary with those based on domestic forms",[3] confirming Bos primigenius for the aurochs. Taxonomists who consider domesticated cattle a subspecies of the wild aurochs should use B. primigenius taurus; those who consider domesticated cattle to be a separate species may use the name B. taurus, which the commission has kept available for that purpose.[4]

Etymology

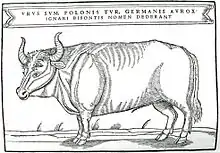

The words aurochs, urus, and wisent have all been used synonymously in English.,[5][6] but the extinct aurochs/urus is a completely separate species from the still-extant wisent, also known as the European bison. The two were often confused, and some 16th-century illustrations of aurochs and wisent have hybrid features.[7] The word urus (/ˈjʊərəs/; plural uri)[5][6] is a Latin word, but was borrowed into Latin from Germanic (cf. Old English/Old High German ūr, Old Norse úr).[5] In German, OHG ūr "primordial" was compounded with ohso "ox", giving ūrohso, which became the early modern Aurochs. The modern form is Auerochse.[8]

The word aurochs was borrowed from early modern German, replacing archaic urochs, also from an earlier form of German. The word is invariable in number in English, though sometimes a back-formed singular auroch and/or innovated plural aurochses occur.[6] The use in English of the plural form aurochsen is nonstandard, but mentioned in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. It is directly parallel to the German plural Ochsen (singular Ochse) and recreates by analogy the same distinction as English ox (singular) and oxen (plural).[9]

Evolution

During the Pliocene, the colder climate caused an extension of open grassland, which led to the evolution of large grazers, such as wild bovines.[8] Bos acutifrons is an extinct species of cattle that has been suggested as an ancestor for the aurochs.[8]

The oldest aurochs remains have been dated to about 2 million years ago, in India. The Indian subspecies was the first to appear.[8] During the Pleistocene, the species migrated west into the Middle East (western Asia), as well as to the east. They reached Europe about 270,000 years ago.[8] The South Asian domestic cattle, or zebu, descended from Indian aurochs at the edge of the Thar Desert; the zebu is resistant to drought. Domestic yak, gayal, and Bali cattle do not descend from aurochs.

The first complete mitochondrial genome (16,338 base pairs) DNA sequence analysis of Bos primigenius from an archaeologically verified and exceptionally well preserved aurochs bone sample was published in 2010,[10] followed by the publication in 2015 of the complete genome sequence of Bos primigenius using DNA isolated from a 6,750-year-old British aurochs bone.[11] Further studies using the Bos primigenius whole genome sequence have identified candidate microRNA-regulated domestication genes.[12]

A DNA study has also suggested that the modern European bison originally developed as a prehistoric cross-breed between the aurochs and the steppe bison.[13][14]

Three wild subspecies of aurochs are recognised. Only the Eurasian subspecies survived until recent times.

- The Eurasian aurochs (B. p. primigenius) once ranged across the steppes and taigas of Europe, Siberia and Central Asia, and East Asia. It is noted as part of the Pleistocene megafauna, and declined in numbers along with other megafauna species by the end of the Pleistocene. The Eurasian aurochs were domesticated into modern taurine cattle breeds around the sixth millennium BCE in the Middle East, and possibly also at about the same time in the Far East. Aurochs were still widespread in Europe during the time of the Roman Empire, when they were widely popular as a battle beast in Roman arenas. Excessive hunting began and continued until the species was nearly extinct. By the 13th century, aurochs existed only in small numbers in Eastern Europe, and the hunting of aurochs became a privilege of nobles, and later royal households. The aurochs were not saved from extinction, and the last recorded live aurochs, a female, died in 1627 in the Jaktorów Forest, Poland, from natural causes. Aurochs were found to have lived on the island of Sicily, having migrated via a land bridge from Italy. After the disappearance of the land bridge, Sicilian aurochs (B. p. siciliae) evolved to be 20% smaller than their mainland relatives due to insular dwarfism.[8] Fossilized specimens were found in Japan, possibly herded with steppe bison.[15][16]

- The Indian aurochs (B. p. namadicus) once inhabited India. It was the first subspecies of the aurochs to appear, at 2 million years ago, and from about 9000 years ago, it was domesticated as the zebu.[17] Fossil remains indicate wild Indian aurochs besides domesticated zebu cattle were in Gujarat and the Ganges area until about 4–5000 years ago. Remains from wild aurochs 4400 years old are clearly identified from Karnataka in South India.[18]

- The North African aurochs (B. p. africanus) once lived in the woodland and shrubland of North Africa.[1] It descended from aurochs populations migrating from the Middle East. The North African aurochs was morphologically very similar to the Eurasian subspecies, so this taxon may exist only in a biogeographic sense.[8] Depictions show that North African aurochs may have had a light saddle marking on its back.[19] This population may have been extinct before the Middle Ages.[8]

Description

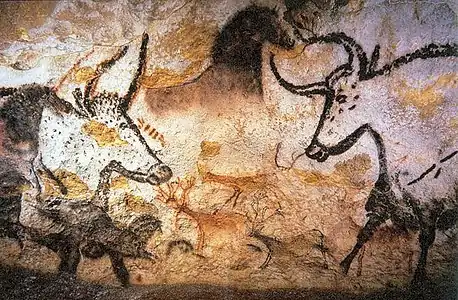

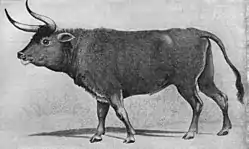

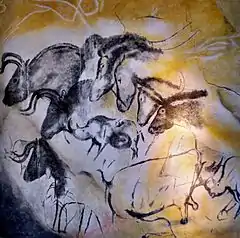

The appearance of the aurochs has been reconstructed from skeletal material, historical descriptions, and contemporaneous depictions, such as cave paintings, engravings, or Sigismund von Herberstein's illustration. The work by Charles Hamilton Smith is a copy of a painting owned by a merchant in Augsburg, which may date to the 16th century. Scholars have proposed that Smith's illustration was based on a cattle/aurochs hybrid, or an aurochs-like breed.[20] The aurochs was depicted in prehistoric cave paintings and described in Julius Caesar's The Gallic War, Book 6, Ch. 28.[21]

Size

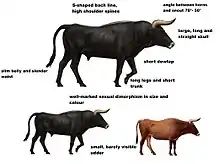

The aurochs were one of the largest herbivores in postglacial Europe, comparable to the European bison. The size of an aurochs appears to have varied by region; in Europe, northern populations were bigger on average than those from the south. For example, during the Holocene, aurochs from Denmark and Germany had an average height at the shoulders of 155–180 cm (61–71 in) in bulls and 135–155 cm (53–61 in) in cows, while aurochs populations in Hungary had bulls reaching 155–160 cm (61–63 in).[22] The body mass of aurochs appears to have shown some variability. Some individuals were comparable in weight to the wisent and the banteng, reaching around 700 kg (1,540 lb), whereas those from the Late Middle Pleistocene are estimated to have weighed up to 1,500 kg (3,310 lb), as much as the largest gaur (the largest extant bovid).[8] The sexual dimorphism between bulls and cows was strongly expressed, with the cows being significantly shorter than bulls on average.

Horns

Because of the massive horns, the frontal bones of aurochs were elongated and broad. The horns of the aurochs were characteristic in size, curvature, and orientation. They were curved in three directions: upwards and outwards at the base, then swinging forwards and inwards, then inwards and upwards. Aurochs horns could reach 80 cm (31 in) in length and between 10 and 20 cm (3.9 and 7.9 in) in diameter.[19] The horns of bulls were larger, with the curvature more strongly expressed than in cows. The horns grew from the skull at a 60° angle to the muzzle, facing forwards.[8]

Body shape

The proportions and body shape of the aurochs were strikingly different from many modern cattle breeds.[8] For example, the legs were considerably longer and more slender, resulting in a shoulder height that nearly equalled the trunk length. The skull, carrying the large horns, was substantially larger and more elongated than in most cattle breeds. As in other wild bovines, the body shape of the aurochs was athletic, and especially in bulls, showed a strongly expressed neck and shoulder musculature. Therefore, the fore hand was larger than the rear, similar to the wisent, but unlike many domesticated cattle.[8] Even in carrying cows, the udder was small and hardly visible from the side; this feature is equal to that of other wild bovines.[8]

Coat colour

The coat colour of the aurochs can be reconstructed by using historical and contemporary depictions. In his letter to Conrad Gesner (1602), Anton Schneeberger describes the aurochs, a description that agrees with cave paintings in Lascaux and Chauvet. Calves were born a chestnut colour. Young bulls changed their coat colour at a few months old to black, with a white eel stripe running down the spine. Cows retained the reddish-brown colour. Both sexes had a light-coloured muzzle.[8] Some North African engravings show aurochs with a light-coloured "saddle" on the back,[19] but otherwise no evidence of variation in coat colour is seen throughout its range. A passage from Mucante (1596) describes the "wild ox" as gray, but is ambiguous and may refer to the wisent. Egyptian grave paintings show cattle with a reddish-brown coat colour in both sexes, with a light saddle, but the horn shape of these suggest that they may depict domesticated cattle.[8] Remains of aurochs hair were not known until the early 1980s.[23]

Colour of forelocks

Some primitive cattle breeds display similar coat colours to the aurochs, including the black colour in bulls with a light eel stripe, a pale mouth, and similar sexual dimorphism in colour. A feature often attributed to the aurochs is blond forehead hairs. Historical descriptions tell that the aurochs had long and curly forehead hair, but none mentions a certain colour for it. Cis van Vuure (2005) says that, although the colour is present in a variety of primitive cattle breeds, it is probably a discolouration that appeared after domestication. The gene responsible for this feature has not yet been identified.[8] Zebu breeds show lightly coloured inner sides of the legs and belly, caused by the so-called zebu-tipping gene. It has not been tested if this gene is present in remains of Indian aurochs.[8]

Behaviour and ecology

Like many bovids, aurochs formed herds for at least a part of the year. These probably did not number much more than 30. If aurochs had social behaviour similar to their descendants, social status was gained through displays and fights, in which both cows and bulls engaged.[19] Indeed, aurochs bulls were reported to often have had severe fights.[8] As in other wild cattle ungulates that form unisexual herds, considerable sexual dimorphism was expressed. Ungulates that form herds containing animals of both sexes, such as horses, have more weakly developed sexual dimorphism.[24]

During the mating season, which probably took place during the late summer or early autumn,[8] the bulls had severe fights, and evidence from the forest of Jaktorów shows these could lead to death. In autumn, aurochs fed up for the winter, and got fatter and shinier than during the rest of the year, according to Schneeberger.[8] Calves were born in spring. According to Schneeberger, the calf stayed at the cow's side, until it was strong enough to join and keep up with the herd on the feeding grounds.[8]

Calves were vulnerable to wolf predation, and, to an extent, brown bears, while healthy adult aurochs probably did not have to fear these predators.[8] In prehistoric Europe, North Africa, and Asia, large predators, such as lions, tigers, and hyenas, were additional predators that most likely preyed on aurochs.[8]

Historical descriptions, like Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico or Schneeberger, tell that aurochs were swift and fast, and could be very aggressive. According to Schneeberger, aurochs were not concerned when a man approached, but when teased or hunted, an aurochs could get very aggressive and dangerous, and throw the teasing person into the air, as he described in a 1602 letter to Gesner.[8]

Habitat and distribution

No consensus exists concerning the habitat of the aurochs. Van Vuure points out that throughout much of the last few thousand years, European landscapes probably consisted of dense forests, and as such, the aurochs were confined to open areas in marshlands along rivers.[25] Comparisons of the ratios of certain mineral isotopes in recovered bones of aurochs from the Mesolithic with domestic cattle has shown they lived in floodplain forests or marshes, areas much wetter than in which modern domesticated cattle live.[25][26] According to the author, such cattle were not able to create and maintain open landscapes without the help of man.[25] While some authors propose that the habitat selection of the aurochs was comparable to the African forest buffalo, others describe the species as inhabiting open grassland, and helping maintain open areas by grazing, together with other large herbivores.[27][28] With its hypsodont jaw, the aurochs was probably a grazer, and had a food selection very similar to domesticated cattle.[8] It was not a browser like many deer species, nor a semi-intermediary feeder like the wisent.[8] Schneeberger describes that during winter, the aurochs ate twigs and acorns, in addition to grasses.[8]

After the beginning of the Common Era, the habitat of aurochs became more fragmented, because of the steadily growing human population. During the last centuries of its existence, the aurochs was limited to remote regions in northeastern Europe.[8]

At one point, the range of the aurochs was from Europe (excluding Ireland and northern Scandinavia), to northern Africa, the Middle East, India, and Central and East Asia.[8][29] Until at least 3,000 years ago, the aurochs was also found in eastern China, where it is recorded at the Dingjiabao Reservoir in Yangyuan County. Most remains in China are known from the area east of 105°E, but the species has also been reported from the eastern margin of the Tibetan plateau, close to the Heihe River.[30] Fossils have been excavated from the Korean Peninsula[31] and the Japanese archipelago, along with those of bison.[15][16]

Relationship with humans

Domestication

The aurochs, which ranged throughout much of Eurasia and Northern Africa during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene, is the wild ancestor of modern cattle. Archaeological evidence shows that domestication occurred independently in the Near East and the Indian subcontinent between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago, giving rise to the two major domestic subspecies observed today: the humpless taurine cattle (European cattle, Bos taurus taurus) and the humped indicine cattle (Zebu, Bos taurus indicus), respectively. This is confirmed by genetic analyses of matrilineal mitochondrial DNA sequences, which reveal a marked differentiation between modern B. t. taurus and B. t. indicus haplotypes, demonstrating their derivation from two genetically divergent wild populations.[10] [32] The sanga cattle (Bos taurus africanus), a zebu-like cattle breed with no back hump, is commonly believed to originate from crosses between humped zebus and taurine cattle breeds. A 1991 study of the bone morphology of domestic taurine cattle from Egypt from the third millennium theorised that sanga cattle were independently domesticated in Africa and that bloodlines of taurine and zebu cattle were introduced only within the last few hundred years.[33] However, a 1996 study of mitochondrial genetics indicates this is highly unlikely.[34]

A number of mitochondrial DNA studies, most recently from the 2010s, suggest that all domesticated taurine cattle originated from about 80 wild female aurochs in the Near East.[35][36] Domestication of the aurochs began in the southern Caucasus and northern Mesopotamia from about the sixth millennium BC.[34] Domesticated cattle and aurochs are so different in size that they have been regarded as separate species; however, large ancient cattle and aurochs have more similar morphological characteristics, with significant differences only in the horns and some parts of the skull.[8][32]

Aurochs were independently domesticated in India. Indian zebu, although domesticated eight to 10 thousand years ago, are related to Indian aurochs (B. p. namadicus) that diverged from the Near Eastern ones some 200,000 years ago. The Near Eastern (B. p. primigenius) and African aurochs (B. p. africanus) groups are thought to have split some 25,000 years ago, probably 15,000 years before domestication.[34]

Aurochs became extinct in Britain during the Bronze Age, and analysis of bones from aurochs that lived about the same time as domesticated cattle has suggested no genetic contribution to modern breeds.[37] Some older studies dispute this. One study has pointed to possible introgression of local aurochs into the "Turano-Mongolian" type of cattle now found in northern China, Mongolia, Korea and Japan,[38] another found small introgression into local Italian breeds,[32] with a later study finding similar results in indigenous British and Irish cattle landraces. In this last study, researchers mapped the draft genome of a British aurochs dated to 6,750 years before present and compared it to the genomes of 73 modern cattle populations and found that traditional cattle breeds of Scottish, Irish, Welsh, and English origin – such as Highland, Dexter, Kerry, Welsh Black, and White Park, had more genetic similarity to the aurochs in question than other populations.[37] Another study concluded that because of this genomic introgression of the aurochs into cattle breeds, one might argue, that in "the bigger picture across the aurochs/cattle range, perhaps several subpopulations of aurochs are not extinct at all" but partially survive in such breeds.[39]

Extinction

By the time of Herodotus (5th century BC), aurochs had disappeared from southern Greece, but remained common in the area north and east of the Echedorus River close to modern Thessaloniki.[40] The last reports of the species in the southern tip of the Balkans date to the 1st century BC, when Varro reported that fierce wild oxen lived in Dardania (southern Serbia) and Thrace.[41] By the 13th century AD, the aurochs' range was restricted to Poland, Lithuania, Moldavia, Transylvania, and East Prussia. Archeological data indicate that they survived in Bulgaria, in the northeastern part of the country and around Sofia, until the 16th - 17th century,[42] in northwestern Transylvania until 14th - 16th century AD and in Romanian Moldavia till probably the beginning of the 17th century AD, almost at the same time as in Poland.[43][44] In Poland, the right to hunt large animals on any land was restricted first to nobles, and then gradually, to only the royal households. As the population of aurochs declined, hunting ceased altogether. The Polish Royal Family used gamekeepers to provide open fields for grazing for the aurochs, exempting them from local taxes in exchange for their service. Poaching aurochs was made a crime punishable by death.[45]

According to a Polish royal survey in 1564, the gamekeepers knew of 38 animals. The last recorded live aurochs, a female, died in 1627 in the Jaktorów Forest, Poland, from natural causes. The causes of extinction were unrestricted hunting, a narrowing of habitat due to the development of farming, and diseases transmitted by domesticated cattle.[8][46]

Breeding of aurochs-like cattle

While all the wild subspecies are extinct, B. primigenius lives on in domesticated cattle, and attempts are being made to breed similar types suitable for filling the extinct subspecies' role in the former ecosystem.

The idea of breeding back the aurochs was first proposed in the 19th century by Feliks Paweł Jarocki.[8] In the 1920s, a first attempt was undertaken by the Heck brothers in Germany with the aim of breeding an effigy (a look-alike) of the aurochs. Starting in the 1990s grazing and rewilding projects brought new impetus to the idea and new breeding-back efforts came underway, this time with the aim of recreating an animal not only with the looks, but also with the behaviour and the ecological impact of the aurochs, to be able to fill the ecological role of the aurochs.

The drive behind reintroduction efforts of the aurochs is largely motivated by a belief that an aesthetically pleasing open park-like landscape is "natural".[47] The former natural European landscapes probably consisted of dense forests, with the aurochs being confined to open areas in marshlands along rivers. Research into the impact of large herbivores on forest growth has concluded that large herbivores are only able to create and maintain an open park-like landscape with the help of man.[25] Grazing behaviour by livestock alters the landscape, which one organisation promotes as "natural grazing" (also called conservation grazing). The Rewilding Europe foundation advocates for "returning" lands to their "natural state" and believes that, without grazing, everything becomes forest.[47] According to one theory, "mosaic landscapes" and gradients between different environments, from open soil to grassland, are important for biodiversity.[48]

Approaches that aim to breed an aurochs-like phenotype do not equate to an aurochs-like genotype. One study proposed that using the mapped out genomes of prehistoric specimens it will be possible to breed back cattle "that are genetically akin to specific original aurochs populations, through selective cross-breeding of local cattle breeds bearing local aurochs-genome ancestry."[39]

Heck cattle

In the early 1920s, two German zoo directors (in Berlin and Munich), the brothers Heinz and Lutz Heck, began a selective breeding program to breed back the aurochs into existence from the descendant domesticated cattle. Their plan was based on the concept that a species is not extinct as long as all its genes are still present in a living population.[49] The result is the breed called Heck cattle. According to van Vuure, it bears little resemblance to what is known about the appearance of the aurochs.[8]

Taurus cattle

The Arbeitsgemeinschaft Biologischer Umweltschutz, a conservation group in Germany, started to crossbreed Heck cattle with southern-European primitive breeds in 1996, with the goal of increasing the aurochs-likeness of certain Heck cattle herds. These crossbreeds are called Taurus cattle. It is intended to bring in aurochs-like features that are supposedly missing in Heck cattle using Sayaguesa Cattle and Chianina, and to a lesser extent Spanish Fighting Cattle (Lidia). The same breeding program is being carried out in Latvia,[50] in Lille Vildmose National Park in Denmark, and in the Hungarian Hortobágy National Park. The program in Hungary also includes Hungarian Grey cattle and Watusi.[51]

Tauros Programme

The Dutch-based Tauros Programme,[52] (initially TaurOs Project) is trying to DNA-sequence breeds of primitive cattle to find gene sequences that match those found in "ancient DNA" from aurochs samples. The modern cattle would be selectively bred to try to produce the aurochs-type genes in a single animal.[53] Starting around 2007, Tauros Programme selected a number of primitive breeds mainly from Iberia and Italy, such as Sayaguesa cattle, Maremmana primitivo, Pajuna cattle, Limia cattle, Maronesa cattle, Tudanca cattle, and others, which already bear considerable resemblance to the aurochs in certain features. Tauros Programme started collaborations with Rewilding Europe[47][54] and European Wildlife,[55][56] two European organizations for ecological restoration and rewilding, and now has breeding herds not only in the Netherlands but also in Portugal, Croatia, Romania, and the Czech Republic. Numerous crossbred calves of the first, second, and third offspring generations have already been born.[57] An ecologist working on the Tauros programme has estimated it will take 7 generations for the project to achieve its aims, possibly by 2025.[48]

Uruz Project

_(8551538660).jpg.webp)

Another back-breeding effort, the Uruz project, was started in 2013 by the True Nature Foundation, an organization for ecological restoration and rewilding.[58] It differs from the other projects in that it is planning to make use of genome editing.[59][60] In 2013 it planned to use either Sayaguesa, Maremmana primitive, Hungarian Grey (Steppe) cattle, Texas Longhorn with wild-type colour or Barrosã cattle.[61]

Auerrind Project

Another back-breeding effort, the Auerrindprojekt,[62][63] was started in 2015 as a conjoined effort[64] of the Experimentalarchäologisches Freilichtlabor Lauresham (run by Lorsch Abbey),[65] the Förderkreis Große Pflanzenfresser im Kreis Bergstraße e.V.[66] and the Landschaftspflegebetrieb Hohmeyer.[67] The five breeds used include Watusi, Chianina, Sayaguesa, Maremmana and Hungarian Grey cattle. The project will not use Heck cattle as they have been deemed too genetically dissimilar to the extinct Aurochs, and it will not use any fighting breeds of cattle, because the breeders prefer to create a docile type of cattle.[68]

Other projects

Scientists of the Polish Foundation for Recreating the Aurochs (PFOT) in Poland hope to use DNA from bones in museums to recreate the aurochs. They plan to return this animal to the forests of Poland. The project has gained the support of the Polish Ministry of the Environment. They plan research on ancient preserved DNA. Polish scientists Ryszard Słomski and Jacek A. Modliński believe that modern genetics and biotechnology make it possible to recreate an animal similar to the aurochs.[69]

Cultural significance

The aurochs was an important game animal appearing in both Paleolithic European and Mesopotamian cave paintings, such as those found at Lascaux and Livernon in France. An archaeological excavation in Israel found traces of a feast held by the Natufian culture around 12,000 B.P., in which three aurochs (and numerous tortoises) were eaten, this appears to be an uncommon occurrence in the culture and was held in conjunction with the burial of an older woman, presumably of some social status.[70] A 2012 archaeological mission in Sidon, Lebanon, discovered the remains numerous animal species, including an aurochs, and a few human bones and plant foods, dating from around 3700 B.P., which appear to have been buried together in some sort of necropolis.[71] A 1999 archaeological dig in Peterborough, England, uncovered the skull of an aurochs. The front part of the skull had been removed, but the horns remained attached. The supposition is that the killing of the aurochs in this instance was a sacrificial act.

..jpg.webp)

Also during antiquity, the aurochs was regarded as an animal of cultural value. Aurochs are depicted on the Ishtar Gate. Aurochs type figurines were made by the Maykop culture in Western Caucasus and by inhabitants of Greece of the Helladic period in Thebes. In the Peloponnese there is a 15th-century B.C. depiction on the so-called violent cup of Vaphio, of hunters trying to capture with nets three wild bulls being probably aurochs,[72] in a possibly Cretan date palm stand. The one of the bulls throws one hunter on the ground while attacking the second with its horns. Despite an earlier perception that the cup was Minoan, it seems to be Mycenaean.[73][74] Greeks and Paeonians hunted aurochs (wild oxen/bulls) and used their huge horns as trophies, cups for wine, and offerings to the gods and heroes. For example, according to Douglas (1927), the ox mentioned by Samus, Philippus of Thessalonica and Antipater as killed by Philip V of Macedon on the foothills of mountain Orvilos, was actually an aurochs; Philip offered the horns, which were 105 cm long and the skin to a temple of Hercules.[40][75]

They survived in the wild in Europe till late in the Roman Empire and in 1847 were believed to be occasionally captured and exhibited in shows (venationes) in Roman amphitheatres such as the colosseum.[76] Aurochs horns were often used by Romans as hunting horns.[77] Julius Caesar described aurochs in Gaul:

... those animals which are called uri. These are a little below the elephant in size, and of the appearance, colour, and shape of a bull. Their strength and speed are extraordinary; they spare neither man nor wild beast which they have espied. These the Germans take with much pains in pits and kill them. The young men harden themselves with this exercise, and practice themselves in this sort of hunting, and those who have slain the greatest number of them, having produced the horns in public, to serve as evidence, receive great praise. But not even when taken very young can they be rendered familiar to men and tamed. The size, shape, and appearance of their horns differ much from the horns of our oxen. These they anxiously seek after, and bind at the tips with silver, and use as cups at their most sumptuous entertainments.

The Hebrew Bible contains numerous references to the untameable strength of the re'em,[78] translated as "bullock" or "wild-ox" in Jewish translations and translated rather poorly in the King James Version as "unicorn", but recognized from the last century by Hebrew scholars as the aurochs.[79][80]

When the aurochs became rarer, hunting it became a privilege of the nobility and a sign of a high social status. The Nibelungenlied describes Siegfried killing aurochs: "Dar nâch sluoc er schiere einen wisent und einen elch / starker ûwer viere und einen grimmen schelch" (Nibelungenlied 937.1-2),[81] meaning "After that, he quickly defeated one wisent and one elk, four strong aurochs, and one terrible schelch."[lower-alpha 1] Aurochs horns were commonly used as drinking horns by the nobility, which led to the fact that many aurochs horn sheaths are preserved today (albeit often discoloured). The drinking horn at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, given to the college on its foundation in 1352, probably by the college's founders, the Guilds of Corpus Christi and the Blessed Virgin Mary, is thought to come from an aurochs.[83] A painting by Willem Kalf depicts an aurochs horn. The horns of the last aurochs bulls, which died in 1620, were ornamented with gold and are located at the Livrustkammaren in Stockholm today.

Schneeberger writes that aurochs were hunted with arrows, nets, and hunting dogs. With the aurochs immobilized, the curly hair on the forehead was cut from the living animal. Belts were made out of this hair and were believed to increase the fertility of women. When the aurochs was slaughtered, a cross-like bone (os cardis) was extracted from the heart. This bone, which is also present in domesticated cattle, contributed to the mystique of the animal and magical powers have been attributed to it.[8]

In eastern Europe, where it survived until nearly 400 years ago, the aurochs has left traces in fixed expressions. In Russia, a drunken person behaving badly was described as "behaving like an aurochs", whereas in Poland, big, strong people were characterized as being "a bloke like an aurochs".[25]

In Central Europe, the aurochs features in toponyms and heraldic coats of arms. For example, the names Ursenbach and Aurach am Hongar are derived from the aurochs. An aurochs head, the traditional arms of the German region Mecklenburg, figures in the coat of arms of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. The aurochs (Romanian bour, from Latin būbalus) was also the symbol of Moldavia; nowadays, they can be found in the coat of arms of both Romania and Moldova. An aurochs head is featured on an 1858 series of Moldavian stamps, the so-called Bull's Heads (cap de bour in Romanian), renowned for their rarity and price among collectors. In Romania there are still villages named Boureni, after the Romanian word for the aurochs. The horn of the aurochs is a charge of the coat of arms of Tauragė, Lithuania, (the name of Tauragė is a compound of taũras "auroch" and ragas "horn"). It is also present in the emblem of Kaunas, Lithuania, and was part of the emblem of Bukovina during its time as an Austro-Hungarian Kronland. The Swiss Canton of Uri is named after the aurochs; its yellow flag shows a black aurochs head. East Slavic surnames Turenin, Turishchev, Turov, and Turovsky originate from the Slavic name of the species tur.[84] In Slovakia, toponyms such as Turany, Turíčky, Turie, Turie Pole, Turík, Turová (villages), Turiec (river and region), Turská dolina (valley) and others are used. Turopolje, a large lowland floodplain south of the Sava River in Croatia, got its name from the aurochs (Croatian: tur).

Aurochs is a commonly used symbol in Estonia. The town of Tartu (and its ancient name Tarvatu, Tarvato or Tarbatu) is likely named after the Estonian word tarvas ("aurochs").[85] The ancient name of another Estonian town Rakvere, Tarvanpää, Tarvanpea or Tarwanpe, also derives from the same source as "Aurochs' Head" in ancient Estonian.[86] The aurochs is nowadays a symbol of Rakvere, with a well known aurochs monument at the Rakvere Castle ruins and several "Rakvere Tarvas" sports clubs.

In 2002, a 3.5-m-high and 7.1-m-long statue of an aurochs was erected in Rakvere, Estonia, for the town's 700th birthday. The sculpture, by artist Tauno Kangro, has become a symbol of the town.[87]

See also

- Ashurnasirpal II's hunting of "wild oxen"

- Chillingham cattle

- Ur (rune)

- American bison (Bison bison)

- Beefalo

- Bison antiquus (antique or ancient bison)

- Bison latifrons (giant bison or long-horned bison)

- Bison priscus (steppe bison)

- Bison

- Bovid hybrid

- Domestic yak

- European bison (Bison bonasus)

- Gaur

- Water buffalo

- Wild water buffalo

- Wild yak

- Wood bison (Bison bison athabascae)

- Żubroń

Footnotes

- The meaning of schelch is uncertain. Suggestions include the bull moose, the Irish elk, the wild horse, or the Eurasian lynx.[82]

Notes

This article incorporates Creative Commons license CC BY-2.5 text from reference.[10]

- Tikhonov, A. (2008). "Bos primigenius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T136721A4332142. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T136721A4332142.en. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Aurochs – Bos primigenius". petermaas.nl. Archived from the original on 20 April 2009.

- "ICZN, Biodiversity Studies BZN Volume 63, Part 3, General Articles & Nomenclatural Notes". 30 September 2006.

- "Opinion 2027 (Case 3010). Usage of 17 specific names based on wild species which are pre-dated by or contemporary with those based on domestic animals (Lepidoptera, Osteichthyes, Mammalia): conserved". Bull. Zool. Nomencl. 60: 81–84. 2003.

- American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th edition (AHD4). Houghton Mifflin, 2000. Headwords aurochs, urus, wisent

- Merriam-Webster Unabridged (MWU). (Online subscription-based reference service of Merriam-Webster, based on Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged. Merriam-Webster, 2002.) s.vv. "aurochs", "urus", "wisent". Accessed 2007-06-02

- Pyle, C. M. (1994). "Some late sixteenth-century depictions of the aurochs (Bos primigenius Bojanus, extinct 1627): New evidence from Vatican MS Urb. Lat. 276". Archives of Natural History. 21 (3): 275–288. doi:10.3366/anh.1994.21.3.275.

- van Vuure, T. (Cis) (2005). Retracing the Aurochs – History, Morphology and Ecology of an extinct wild Ox. Sofia-Moscow: Pensoft Publishers. ISBN 954-642-235-5.

- Crystal, David (2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53033-4.

- Edwards, C.J.; Magee, D.A.; Park, S.D.E.; McGettigan, P.A.; Lohan, A.J.; et al. (2010). "A Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequence from a Mesolithic Wild Aurochs (Bos primigenius)"". PLOS One. 5 (2): e9255. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9255E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009255. PMC 2822870. PMID 20174668.

- Park, Stephen D. E.; Magee, David A.; McGettigan, Paul A.; Teasdale, Matthew D.; Edwards, Ceiridwen J.; Lohan, Amanda J.; Murphy, Alison; Braud, Martin; Donoghue, Mark T. (26 October 2015). "Genome sequencing of the extinct Eurasian wild aurochs, Bos primigenius, illuminates the phylogeography and evolution of cattle". Genome Biology. 16: 234. doi:10.1186/s13059-015-0790-2. PMC 4620651. PMID 26498365.

- Braud, Martin; Magee, David A.; Park, Stephen D. E.; Sonstegard, Tad S.; Waters, Sinead M.; MacHugh, David E.; Spillane, Charles (2017). "Genome-Wide microRNA Binding Site Variation between Extinct Wild Aurochs and Modern Cattle Identifies Candidate microRNA-Regulated Domestication Genes". Frontiers in Genetics. 8: 3. doi:10.3389/fgene.2017.00003. PMC 5281612. PMID 28197171.

- Soubrier, J.; Gower, G.; Chen, K.; Richards, S. M.; Llamas, B.; Mitchell, K. J.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Kosintsev, P.; Lee, M. S. Y.; Baryshnikov, G.; Bollongino, R.; Bover, P.; Burger, J.; Chivall, D.; Crégut-Bonnoure, E.; Decker, J. E.; Doronichev, V. B.; Douka, K.; Fordham, D. A.; Fontana, F.; Fritz, C.; Glimmerveen, J.; Golovanova, L. V.; Groves, C.; Guerreschi, A.; Haak, W.; Higham, T.; Hofman-Kamińska, E.; Immel, A.; Julien, M.-A.; Krause, J.; Krotova, O.; Langbein, F.; Larson, G.; Rohrlach, A.; Scheu, A.; Schnabel, R. D.; Taylor, J. F.; Tokarska, M.; Tosello, G.; van der Plicht, J.; van Loenen, A.; Vigne, J.-D.; Wooley, O.; Orlando, L.; Kowalczyk, R.; Shapiro, B.; Cooper, A. (2016). "Early cave art and ancient DNA record the origin of European bison". Nature Communications. 7 (13158): 13158. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713158S. doi:10.1038/ncomms13158. PMC 5071849. PMID 27754477.

- Cooper, Alan; Soubrier, Julien; Mills, Robyn (19 October 2016), The Higgs Bison - mystery species hidden in cave art, The University of Adelaide, retrieved 13 January 2017

- Kurosawa Y. "モノが語る牛と人間の文化 - ② 岩手の牛たち" (PDF). LIAJ News No.109. Oshu city Cattle Museum: 29–31. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- HASEGAWA Y.,OKUMURA Y., TATSUKAWA H. (2009). "First record of Late Pleistocene Bison from the fissure deposits of the Kuzuu Limestone, Yamasuge,Sano-shi,Tochigi Prefecture,Japan" (PDF). Bull.Gunma Mus.Natu.Hist.(13). Gunma Museum of Natural History and Kuzuu Fossil Museum: 47–52. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- In the Light of Evolution III: Two Centuries of Darwin. National Academies Press. 2009. p. 96.

- Shanyuan Chen, Bang-Zhong Lin, Mumtaz Baig, Bikash Mitra, Ricardo J. Lopes, António M. Santos, David A. Magee, Marisa Azevedo, Pedro Tarroso, Shinji Sasazaki, Stephane Ostrowski, Osman Mahgoub, Tapas K. Chaudhuri, Ya-ping Zhang, Vânia Costa, Luis J. Royo, Félix Goyache, Gordon Luikart, Nicole Boivin, Dorian Q. Fuller, Hideyuki Mannen, Daniel G. Bradley, and Albano Beja-Pereira. "Zebu Cattle Are an Exclusive Legacy of the South Asia Neolithic", Mol Biol Evol (2010) 27(1): 1-6 first published online 21 September 2009

- Frisch, Walter (2010). Der Auerochs: Das europäische Rind. ISBN 978-3-00-026764-2.

- Pyle, C. M. (1995). "Update to: "Some late sixteenth-century depictions of the aurochs (Bos primigenius Bojanus, extinct 1627): New evidence from Vatican MS Urb. Lat. 276"". Archives of Natural History. 22 (3): 437–438. doi:10.3366/anh.1995.22.3.437.

- "The Internet Classics Archive – The Gallic Wars by Julius Caesar". classics.mit.edu. Book 6, Ch. 28 Translator. W. A. McDevitte. Translator. W. S. Bohn. 1st Edition. New York. Harper & Brothers. 1869. Harper's New Classical Library

- Kysely, René (2008). Aurochs and potential crossbreeding with domestic cattle in Central Europe in the Eneolithic period. A metric analysis of bones from the archaeological site of Kutná Hora-Denemark (Czech Republic). Anthropozoologica.

- Ryder, M. L. (1984). "The first hair remains from an aurochs (Bos primigenius) and some medieval domestic cattle hair". Journal of Archaeological Science. 11: 99–101. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(84)90045-1.

- Bunzel-Drüke, Finck, Kämmer, Luick, Reisinger, Riecken, Riedl, Scharf & Zimball: "Wilde Weiden: Praxisleitfaden für Ganzjahresbeweidung in Naturschutz und Landschaftsentwicklung

- van Vuure, T. (Cis) (2002). "History, , Morphology and Ecology of the Aurochs (Bos primigenius)" (PDF). Lutra. 45 (1).

- Anthony H. Lynch Julie Hamilton & Robert E. M. Hedges (2008). Where the Wild Things Are: Aurochs and Cattle in England.

- Beutler, Axel (1996). Die Großtierfauna Europas und ihr Einfluss auf Vegetation und Landschaft.

- Magret Bunzel-Drüke; Joachim Drüke & Henning Vierhaus (2001). Der Einfluss von Großherbivoren auf die Naturlandschaft Mitteleuropas.

- McKenzie, Steven (17 February 2010). "Ancient giant cattle genome first". BBC News.

- Zong, G. (1984). "A record of Bos primigenius from the Quaternary of the Aba Tibetan Autonomous Region (translation by Jeremy Dehut, April 1991)" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 22 (#3): 239–245. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- Yeong-Seok Jo, John T. Baccus, John Koprowski, 2018, Mammals of Korea, p.30, National Institute of Biological Resources of Korea

- Beja-Pereira, Albano; Caramelli, David; Lalueza-Fox, Carles; Vernesi, Cristiano; Ferrand, Nuno; Casoli, Antonella; Goyache, Felix; Royo, Luis J.; Conti, Serena; Lari, Martina; Martini, Andrea; Ouragh, Lahousine; Magid, Ayed; Atash, Abdulkarim; Zsolnai, Attila; Boscato, Paolo; Triantaphylidis, Costas; Ploumi, Konstantoula; Sineo, Luca; Mallegni, Francesco; Taberlet, Pierre; Erhardt, Georg; Sampietro, Lourdes; Bertranpetit, Jaume; Barbujani, Guido; Luikart, Gordon; Bertorelle, Giorgio (June 2006). "The origin of European cattle: Evidence from modern and ancient DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (21): 8113–8118. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.8113B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509210103. PMC 1472438. PMID 16690747.

- Grigson, Caroline (1991). "An African origin for African cattle? — some archaeological evidence". African Archaeological Review. 9 (1): 119–144. doi:10.1007/BF01117218. S2CID 162307756.

- Bradley, DG; MacHugh, DE; Cunningham, P; Loftus, RT (1996). "Mitochondrial diversity and the origins of African and European cattle". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (10): 5131–5. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.5131B. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.10.5131. PMC 39419. PMID 8643540.

- Molecular Biology and Evolution, 14 March 2012.

- "Modern Taurine Cattle Descended from Small Number of Near-Eastern Founders". Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Park, Stephen D E; Magee, David A.; McGettigan, Paul A.; Teasdale, Matthew D.; Edwards, Ceiridwen J.; Lohan, Amanda J.; Murphy, Alison; Braud, Martin; Donoghue, Mark T.; Liu, Yuan; Chamberlain, Andrew T.; Rue-Albrecht, Kévin; Schroeder, Steven; Spillane, Charles; Tai, Shuaishuai; Bradley, Daniel G.; Sonstegard, Tad S.; Loftus, Brendan J.; MacHugh, David E. (26 October 2015). "Genome sequencing of the extinct Eurasian wild aurochs, Bos primigenius, illuminates the phylogeography and evolution of cattle". Genome Biology. 16 (1): 234. doi:10.1186/s13059-015-0790-2. PMC 4620651. PMID 26498365.

- Hideyuki Mannen; et al. (August 2004). "Independent mitochondrial origin and historical genetic differentiation in North Eastern Asian cattle" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, Volume 32, issue 2. pp. 539–544. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (2016). "The Draft Genome of Extinct European Aurochs and its Implications for De-Extinction". Open Quaternary. 2. doi:10.5334/oq.25.

- "Ηρόδοτος" 5th century BC: Πολύμνια.

- Kitchell, K.F. 2013: Animals in the Ancient Word from A to Z.

- Boev, Z. (2016). "Subfossil Vertebrate Fauna from Forum Serdica (Sofia, Bulgaria), 16-18th Century AD". Acta Zoologica Bulgarica. 68 (3): 415–424.

- Bejenaru, L.; Stanc, S.; Popovici, M.; Balasescu, A.; Cotiuga, V. (2013). "Holocene subfossil records of the auroch (Bos primigenius) in Romania". The Holocene. 23 (4): 603–614. Bibcode:2013Holoc..23..603B. doi:10.1177/0959683612465448. S2CID 131580290.

- Nemeth, A.; Barany, A.; Csorba, G.; Magyari, E.; Pazonyi, P.; Palfy, J. (2016). "Holocene mammal extinctions in the Carpathian Basin: A review" (PDF). Mammal Review. 47 (1): 38–52. doi:10.1111/mam.12075.

- Newman, Lenore. Lost feast: Culinary extinction and the future of food. Toronto: ECW Press. pp. 66–67.

- Rokosz', Mieczyslaw (1995). "History of the Aurochs (Bos Taurus Primigenius) in Poland" (PDF). Animal Genetics Resources Information. Food and Agriculture Organization. 16: 5–12. doi:10.1017/s1014233900004582. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2013.

- Rewilding Europe: “Tauros Programme.” Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Monks, Kieron. "The wild, extinct supercow returning to Europe". cnn. CNN. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- Heck, H. (1951). "The Breeding-Back of the Aurochs". Oryx. 1 (3): 117–122. doi:10.1017/S0030605300035286.

- Margret Bunzel-Drüke. "Projekt Taurus – En økologisk erstatning for uroksen. Translated into Danish by Karsten Thomsen. Lohne: ABU 2004; Århus: Nepenthes, 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- Uffe Gjøl Sørensen. "Vildokserne ved Lille Vildmose 2003–2010. Status rapport med anbefalinger til projektets forvaltning København: UG Sørensen Consult, 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2013.

- "Stichting Taurus Vee". 2010. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.

- Stephan Faris (12 February 2010). "Breeding Ancient Cattle Back from Extinction". TIME.

- Rewilding Europe: “Rewilding Partners.” Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- European Wildlife: “How we work.” Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- European Wildlife (13 April 2011): “The Aurochs is coming back to European forests and grasslands.” Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Stichting Taurus, Official website".

- "True Nature Foundation Starts International Project To Bring Back The Aurochs". Kjprnews.com. 26 October 2013. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Uruz Project". True Nature Foundation. 2014. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- True Nature Foundation: “Aurochs: Species Restoration.” Archived 16 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Gineke Mons (3 October 2013). "Gentechnologie voor fokken oeros". melkvee.nl. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Auerrindprojekt. Official website. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Lorsch Abbey website: “The Aurcattle project.” Archived 18 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- Auerrindprojekt: “Partner.” Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Kloster Lorsch (Lorsch Abbey): Freilichtlabor Lauresham: Allgemeine Informationen. Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Official website. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Förderkreis Große Pflanzenfresser im Kreis Bergstraße e.V. Official website. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Landschaftspflegebetrieb Hohmeyer Official website. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Gulf Times - Scientists Work to Bring Back the Aurochs, or something like it

- "Polish geneticists want to recreate the extinct auroch Science and Scholarship in Poland". Polish Press Agency (PAP). 28 November 2007. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013.

- Munro, Natalie D.; Grosman, Leore (31 August 2010). "Early evidence (ca. 12,000 B.P.) for feasting at a burial cave in Israel". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (35): 15362–15366. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10715362M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1001809107. PMC 2932561. PMID 20805510.

- Makarem, May (11 July 2012). "Et si Europe était sidonienne?". L'Orient Le Jour. Beirut. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- Ajmone-Marsan, P.; Garcia, J.F.; Lenstra, J.A. (2010). "On the Origin of Cattle: How Aurochs Became Cattle and Colonized the World". Evolutionary Anthropology. 19 (#4): 148–157. doi:10.1002/evan.20267. S2CID 86035650.

- Davis, E.N. (1974). "The Vapheio Cups: One Minoan and One Mycenean?". The Art Bulletin. 56 (4): 472–487. doi:10.1080/00043079.1974.10789932.

- De Grummond, W.W. (1980). "Hands and Tails on the Vapheio Cups". American Journal of Archaeology. 84 (#3): 335–337. doi:10.2307/504710. JSTOR 504710.

- Douglas, N. 1927: Birds and Beasts of the Greek Anthology. Florence.

- The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol III, (1847), London, Charles Knight, p.368.

- Vuure, Cis van; Vuure, T. van (2005). Retracing the Aurochs: History, Morphology and Ecology of an Extinct Wild Ox. Coronet Books Incorporated. ISBN 978-954-642-235-4.

- (Strong's # 07214) in the Bible (Numbers 23:22 and 24:8, Deuteronomy 33:17, Job 39:9–10, Psalms 22:21, 29:6, 92:10 and Isaiah 34:7)

- The identification was first made by Johann Ulrich Duerst, Die Rinder von Babylonian, Assyrien und Ägypten(Berlin, 1899:7-8), and was generally accepted, as by Salo Jonas, "Cattle Raising in Palestine" Agricultural History 26.3 (July 1952), pp. 93-104

- The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Entry for 'Wild Ox'. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 1939.

- Heinzle, Joachim, ed. (2013). Das Nibelungenlied und die Klage: Nach der Handschrift 857 der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen. Deutscher Klassiker. p. 300.

- Heinzle, Joachim, ed. (2013). Das Nibelungenlied und die Klage: Nach der Handschrift 857 der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen. Deutscher Klassiker. p. 1247.

- "Corpus Drinking Horn". 3 December 2012.

- Fedosyuk, Yu. A. Russian Surnames. Popular Etymological Dictionary (6th ed.).

- Tartu - Dictionary of Estonian Place Names

- Rakvere - Dictionary of Estonian Place Names

- "Rakvere linn" (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 19 July 2011.

References

- Bunzel-Drüke, M. 2001. Ecological substitutes for Wild Horse (Equus ferus Boddaert, 1785 = E. przewalslii Poljakov, 1881) and Aurochs (Bos primigenius Bojanus, 1827). Natur- und Kulturlandschaft, Höxter/Jena, 4, 10 p. AFKP. Online pdf (298 kB)

Further reading

- Heptner, V. G. ; Nasimovich, A. A. ; Bannikov, A. G. ; Hoffman, R. S. (1988) Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume I, Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation

- Sparavigna, Amelia (2008). "The Pleiades: the celestial herd of ancient timekeepers". arXiv:0810.1592 [physics.hist-ph].

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aurochs. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Aurochs. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Aurochs. |