Burgundian treaty of 1548

The Burgundian treaty of 1548 (ratified on 26 June), also known as the Transaction of Augsburg,[1] settled the status of the Habsburg Netherlands within the Holy Roman Empire.

History

Essentially the work of Viglius van Aytta, it represents a first step towards the emergence of the Netherlands as an independent territory.[1] It was made possible politically by the French loss of Artois and Flanders. Administratively, a chancellery and tribunal was established at Mechelen which for the first time had as its jurisdiction "the Netherlands" exclusively. The treaty resulted in a significant shift of territories from the Lower Rhenish-Westphalian Circle to the Burgundian Circle. The newly formed administrative division of the empire now united all Burgundian territories, which were no longer subject to the Reichskammergericht. To compensate for its territorial gain, the Burgundian Circle was now obliged to pay taxes equivalent to those of two prince-electorates, and in war taxes towards the Turkish Wars even equivalent to three prince-electorates.

To ensure that the Burgundian territory now united in the Burgundian Circle would remain under a single administration, Charles V in the following year promulgated the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549 which declared the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands a single indivisible possession not to be divided in future inheritance.[1]

The consequence of these attempts at reducing the fragmentation of the government of the Holy Roman Empire was the separation of the Netherlands as an entity apart from the remaining empire, forming an important step towards the formation of the Dutch Republic in 1581.

Territories

The treaty, written in New Latin, stipulates in Article 15 that the territories mentioned are to become a single unit that will be passed on undivided to the next generations after Charles V (speaking in majestic plural) through hereditary succession:

(original text) Nimirum, nos veros, haereditarios & supremos Dominos dictarum nostrarum provinciarum Patrimonialium Belgicarum, pro Nobis, nostris haeredibus & successoribus, simul dictae nostrae Provinciae Patrimoniales Belgicae, nominatim Ducatus Lotharingiae, Brabantiae, Limburgi, Luxemburgi, Geldriae; Comitatus Flandriae, Artesiae, Burgundiae, Hannoniae, Hollandiae, Selandiae, Namurci, Zutphaniae; Marchionatus S. R. Imperii, Dominia Frisiae, Ultraiecti, Transisalaniae, Groningae, Falcomontis, Dalhemii, Salinis, Mechliniae & Traecti, una cum omnibus eorundem appendicibus & incorporationibus, Principatibus, Praelaturis, Dignitatibus, Comitatibus, Baroniis & Dominiis ad ea pertinentibus Vasallis & appendicibus, futuros in posterum & semper sub protectione, custodia, conservatione & auxilio Imperatorum & Regum Romanorum & S. R. I. eosque fruituros libertatibus ac iuribus eiusdem, & per dictos Imperatores & Reges Romanorum, & status dicti S. R. I. semper, sicut alii Principes, status & membra eiusdem Imperii, defendos, conservandos, fovendos, & fideliter iuvandos.[2]

(modern English) Evidently, our aforementioned Patrimonial Belgian Provinces, for Ourselves, our heirs and successors, us [being] the real, hereditary and supreme Lords of our aforementioned Patrimonial Belgian provinces, namely the Duchies of Lotharingia, Brabant, Limburg, Luxemburg, and Guelders; the Counties of Flanders, Artois, Burgundy, Hainaut, Holland, Zeeland, Namur, and Zutphen; the March of the Holy Roman Empire; the Lordships of Frisia, Utrecht, Overijssel, Groningen, Valkenburg, Dalhem, Salins, Mechelen, and Maastricht, along with all of their appendages and incorporations, princes, prelatures, dignitaries, counts, barons and lords that belong to certain vassals and appendices, will in the future be one, and always under the protection, custody, conservation and assistance of the Emperors and Kings of the Romans and the Holy Roman Empire, and will enjoy the liberties and rights of the same [Empire], and will forever after be faithfully defended, conserved, supported and assisted by the aforementioned the Emperors and Kings of the Romans and the Holy Roman Empire, just like the other princes, states and members of the same Empire.[note 1]

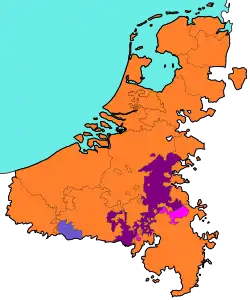

-en.png.webp) Imperial Circles in 1512.

Imperial Circles in 1512.-en.svg.png.webp) Imperial Circles in 1560.

Imperial Circles in 1560.

Notes

- The translation of the names of the territories is partially based on the Dutch publication Geschiedenis der staatsinstellingen (1922).[3]

References

- van Gelderen, Martin (2002). The Political Thought of the Dutch Revolt 1555-1590. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780521891639. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Kahlen, Ludewig Martin (1744). Corpus iuris publici, Das ist, Vollständige Sammlung der wichtigsten Grundgesetze des Heiligen Römischen Reichs Deutscher Nation, gesammelt, verbessert, mit Anmerkungen under Parallelen, wie auch einer Vorrede versehen. Göttingen: Schmid Brothers. p. 389. Retrieved 19 December 2019. (Latin and German)

- Johan Rudolph Thorbecke, Robert Fruin en Herman Theodoor Colenbrander (1922). "2. Verhouding tot het Rijk van de Zeventien Provinciën". Geschiedenis der staatsinstellingen in Nederland tot de dood van Willem II. Universiteit Leiden. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

Sources

- Rachfahl, Felix (1900). "Die Trennung der Niederlande vom deutschen Reiche". Westdeutsche Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kunst. 19: 79–119.

- Mout, Nicolette (1995). "Die Niederlande und das Reich im 16. Jahrhundert". In Press, Volker; Stievermann, Dieter (eds.). Alternativen zur Reichsverfassung in der Frühen Neuzeit?. pp. 143–168.

- Dotzauer, Winfried (1998). Die deutschen Reichskreise (1383–1806). Geschichte und Aktenedition. Steiner. pp. 390 ff., 565 ff. ISBN 3-515-07146-6.