Habsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands (Dutch: Habsburgse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas des Habsbourg), in Latin referred to as Belgica, is the collective name of Renaissance period fiefs in the Low Countries held by the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. The rule began in 1482, when the last Valois-Burgundy ruler of the Netherlands, Mary, wife of Maximilian I of Austria, died.[1] Their grandson, Emperor Charles V, was born in the Habsburg Netherlands and made Brussels one of his capitals.[2][3]

Habsburg Netherlands | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1482–1794 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Status | Personal union of Imperial fiefs within Empire | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Brussels | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Dutch, Low Saxon, West Frisian, Walloon, Luxembourgish, French | ||||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||||

• Inherited by House of Habsburg | 1482 | ||||||||||||

• Incorporated into Burgundian Circle | 1512 | ||||||||||||

| 1549 | |||||||||||||

• Inherited by Habsburg Spain | 1556 | ||||||||||||

| 30 January 1648 | |||||||||||||

| 7 March 1714 | |||||||||||||

| 18 September 1794 | |||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | NL | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

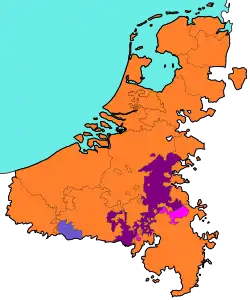

Becoming known as the Seventeen Provinces in 1549, they were held by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556, known as the Spanish Netherlands from that time on.[4] In 1581, in the midst of the Dutch Revolt, the Seven United Provinces seceded from the rest of this territory to form the Dutch Republic. The remaining Spanish Southern Netherlands became the Austrian Netherlands in 1714, after Austrian acquisition under the Treaty of Rastatt. Habsburg rule ended with the annexation by the revolutionary French First Republic in 1795.

Geography

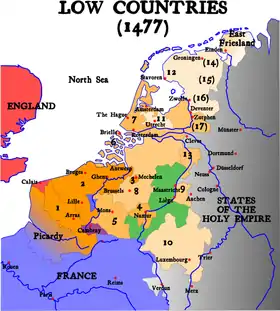

The Habsburg Netherlands was a geo-political entity covering the whole of the Low Countries (i.e. the present-day Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and most of the modern French département of Nord-Pas-de-Calais) from 1482 to 1581.

Already under the Holy Roman Empire rule of the Burgundian duke Philip the Good (1419–1467), the provinces of the Netherlands began to grow together, whereas previously they were split with being either the tributary of the French Kingdom or of Burgundy under the Holy Roman Empire banner. The collected fiefdoms were Flanders, Artois and Mechelen, Namur, Holland, Zeeland and Hainaut, Brabant, Limburg and Luxembourg were ruled in personal union by the Valois-Burgundy monarchs and represented in the States-General assembly. The centre of the Burgundian possessions was the Duchy of Brabant, where the Burgundian dukes held court in Brussels.

Philip's son Duke Charles the Bold (1467–1477) also acquired Guelders and Zutphen and even hoped for the royal title from the hands of the Habsburg emperor Frederick III by marrying their children Mary and Maximilian. Deeply disappointed, he entered into the disastrous Burgundian Wars and was killed in the Battle of Nancy.

History

Upon the death of Mary of Burgundy in 1482, her substantial possessions including the Burgundian Netherlands passed to her son, Philip the Handsome. Through his father Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor from 1493, Philip was a Habsburg scion, and so the period of the Habsburg Netherlands began. The period 1481–1492 saw the Flemish cities revolt and Utrecht embroiled in civil war, but by the turn of the century both areas had been pacified by the Austrian rulers.

Philip's son Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, born in Ghent, succeeded his father in 1506, when he was still a six-year-old minor. His paternal grandfather, Emperor Maximilian I, incorporated the Burgundian heritage into the Burgundian Circle, whereafter the territories in the far west of the Empire developed a certain grade of autonomy. Attaining full age in 1515, Charles went on to rule his Burgundian heritage as a native Netherlander. He acquired the lands of Overijssel and the Bishopric of Utrecht (see Guelders Wars), purchased Friesland from Duke George of Saxony and regained Groningen and Gelderland. His Seventeen Provinces were re-organised in the 1548 Burgundian Treaty, whereby the Imperial estates represented in the Imperial Diet at Augsburg acknowledged a certain autonomy of the Netherlands. It was followed by a pragmatic sanction by the Emperor the next year, which established the Seventeen Provinces as an entity separate from the Empire and from France.

Following a series of abdications between 1555 and 1556, Charles V divided the House of Habsburg into an Austrian-German and a Spanish branch. His brother Ferdinand I became suo jure monarch in Austria, Bohemia and Hungary, as well as the new Holy Roman Emperor. Philip II of Spain, Charles' son, inherited he Seventeen Provinces and incorporated them into the Spanish Crown (which included also south Italy and the American possessions). King Philip II of Spain became infamous for his despotism, and Catholic persecutions sparked the Dutch Revolt and the Eighty Years' War. The Spanish hold on the northern provinces was more and more tenuous. In 1579 the northern provinces established the Protestant Union of Utrecht, in which they declared themselves independent as the Seven United Provinces by the 1581 Act of Abjuration.

After the secession of 1581, the southern provinces, called "'t Hof van Brabant" (of Flandria, Artois, the Tournaisis, Cambrai, Luxembourg, Limburg, Hainaut, Namur, Mechelen, Brabant, and Upper Guelders) remained with the House of Habsburg until the French Revolutionary Wars. After the extinction of the Spanish Habsburgs and the War of the Spanish Succession, the southern provinces were also known as the Austrian Netherlands from 1715 onwards.

Rulers

- 1482–1506 Philip I of Castile as Duke of Burgundy, Maximilian I, his father, as regent (1482–1493), Margaret of York, his stepgrandmother, governess (1489–1493)

- 1506–1556 Charles V as Duke of Burgundy, as Holy Roman Emperor from 1519.

- 1556–1581 Philip II as King of Spain

The provinces were ruled on their behalf by a governor (stadtholder or landvoogd):

- 1489–1493 Margaret of York, dowager Duchess of Burgundy

- 1506–1507 William de Croÿ, Marquis d'Aerschot

- 1507–1530 Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Savoy

- 1531–1555 Mary of Hungary

- 1555–1559 Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy

- 1559–1567 Margaret of Parma

- 1567–1573 Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba

- 1573–1576 Luis de Requesens y Zúñiga

- 1576–1578 John of Austria

- 1578–1592 Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma

In 1578 the Dutch insurgents appointed Archduke Matthias of Austria governor, though he could not prevail and resigned before the 1581 Act of Abjuration.

See also

References

- Sicking, L. H. J. (2004-01-01). Neptune and the Netherlands: State, Economy, and War at Sea in the Renaissance. BRILL. p. 13. ISBN 9004138501.

- "How Brussels became the capital of Europe 500 years ago". The Brussels Times. 2017-04-21. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- Jr, Everett Jenkins (2015-05-07). The Muslim Diaspora (Volume 2, 1500-1799): A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. McFarland. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4766-0889-1.

- Kamen, Henry (2014-03-26). Spain, 1469–1714: A Society of Conflict. Routledge. ISBN 9781317755005.