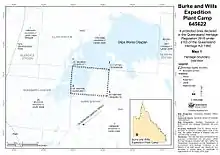

Burke and Wills Plant Camp

Burke and Wills Plant Camp is a heritage-listed campsite near Betoota within the locality of Birdsville, Shire of Diamantina, Queensland, Australia. It is also known as Return Camp 46 and Burke and Wills Camp R46. It was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 11 December 2008.[1]

| Burke and Wills Plant Camp | |

|---|---|

Location of Burke and Wills Plant Camp in Queensland  Burke and Wills Plant Camp (Australia) | |

| Location | Near Betoota, Shire of Diamantina, Queensland, Australia |

| Coordinates | 25.1526°S 139.866°E |

| Design period | 1840s - 1860s (mid-19th century) |

| Official name | Burke and Wills "Plant Camp", Return Camp 46, Buke and Wills Camp R46 |

| Type | protected area (archaeological) |

| Designated | 11 December 2008 |

| Reference no. | 645622 |

| Significant period | 1861 |

| Significant components | blazed tree/dig tree/marker tree, artefact field |

History

The Burke and Wills Plant Camp on Durrie Station is associated with explorers Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills. On the 3 April 1861, on their return trip from the Gulf of Carpentaria, the Burke and Wills expedition were approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) north of the present day Birdsville. That evening Wills made his last astronomical observations and then "planted" his instruments and associated equipment, presumably in a shallow hole, on an unnamed creek near return camp XLVI (also known Camp R46 or Plant Camp). This return trip was a desperate race to reach their depot camp number LXV - the site of the famous Dig Tree located close to the border with South Australia and near the present Nappa Merrie Homestead.[1]

Burke, the leader of the expedition, was born in 1821 in County Galway, Ireland, of Protestant gentry. Following an education at the Woolwich Academy, the young Burke served as a lieutenant in the Austrian cavalry and later the Irish Mounted Constabulary, before emigrating to Australia in 1853. After several postings with the Victorian Police, Burke was appointed to lead the Victorian Exploring Expedition, a position he had anxiously and diligently pursued. Wills, born in Devon England in 1834, trained in medicine. He migrated to Australia in 1853 and after a short stint working as a shepherd at Deniliquin, New South Wales, Wills assisted his father with his medical practice at Ballarat, Victoria. Wills later studied surveying and astronomy, and accompanied the expedition as astronomer, surveyor, and third-in-command, behind camel master George Landells.[1]

The Victorian Exploring Expedition was undertaken in the spirit of previous epics such as Edward Eyre's journey between Western Australia and South Australia in 1840, and Ludwig Leichhardt's 1844-1845 trek from the Darling Downs in Queensland to Port Essington near Darwin. Organised by the Royal Society of Victoria and supported by the government, the expedition's objectives were hazy, beyond the desire to make the already-prosperous colony mightier by taking the lead in exploration efforts. The expedition would prove extremely expensive both financially and in lives, yet was ultimately successful in its bid to beat South Australia's John McDouall Stuart to the first north-south crossing of the continent.[1]

On 20 August 1860, a large crowd in Melbourne provided a farewell for the explorers. The party comprised fifteen men, twenty-six Indian camels with their drivers, packhorses, wagons, food and supplies. In early October the party reached Menindee on the Darling River. Burke had already begun to shed baggage, determined to travel light and fast, leaving behind much of the equipment and some provisions at Balranald. Burke left more provisions at Menindee. He also quarrelled with Landells, who subsequently resigned. Burke promoted Wills to second-in-charge and engaged local man William Wright as third officer. Despite having received clear instructions that he was to establish his main base camp at Cooper's Creek, Burke pressed on quickly with an advance party of eight, leaving the remainder of the men and stores under the charge of Wright. Wright lingered at Menindee for three months, contrary to Burke's orders to proceed to Coopers' Creek as soon as possible, and Wright failed to arrive at Cooper's Creek with the reserve provisions and transport before Burke returned from the Gulf of Carpentaria. On 6 December 1860 Burke and his seven men established Camp LXV (65) at Cooper's Creek, having halted at several other spots along the Creek during the preceding three-and-a-half weeks while searching for the best location for a longer-term depot. Here Burke split his party once again, and on 16 December pressed on to the Gulf. This northern party was made up of Burke as party leader, Wills as second-in-command and astronomer, navigator and meteorologist, King as attendant to the party's camels, and Gray as camp organizer. Brahe, Thomas McDonough, William Patten and Dost Mahomet were instructed by Burke to wait for at least three months (the more cautious Wills preferred four months), before retracing their steps homewards via the Darling River. During their stay at Camp LXV, Brahe's party erected a timber stockade to protect themselves and their supplies from the unwanted interest of local Aborigines.[1]

Following a line to the northeast of Stuart's proposed track, Burke and his team arrived at the Little Bynoe River on 11 February 1861. By this time, they were 57 days out from Cooper's Creek and 13 days over that planned. As they were running low on stores and concerned about meeting the remainder of the exploration party at Cooper's Creek, Burke and Wills left Gray and King at Camp 119 and pushed further north through the mangroves in an attempt to reach the Gulf of Carpentaria coast. However, after three days of difficult travel, they returned south picking up Gray and King.[1]

The return trip from the Gulf of Carpentaria became a desperate race to reach the depot camp on Cooper's Creek on low rations and with failing camels. On 3 April 1861, the Burke and Wills Expedition were approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) north of present-day Birdsville. Burke on that day gave an order "for leaving behind everything but the grub and just what we carry on our backs." That evening Wills made his last astronomical observations and then, according to the notes in his astronomical journal, "planted" his equipment in a shallow hole on an unnamed creek near Camp RXLVI (Camp R46).[1]

Between February 14 and April 21, the four men, with Gray sickening, continued to struggle back towards Cooper's Creek. Gray became increasingly ill suffering from "pain in his head and limbs". His condition continued to deteriorate until he died on the morning of April 17.[1]

On the morning of 21 April 1861, William Brahe and his party of three others including the seriously-injured Patten, left for Menindee. Burke's party reached Camp LXV that same evening with his two surviving though exhausted camels and with perilously low stores. Brahe had left messages carved into the Dig Tree pointing to the cache of supplies. Subsequent events would prove to be a litany of missed opportunities and failure to communicate. A week after their departure from Camp LXV, Brahe met with Wright's party, heading north and finally en route to Cooper's Creek. Brahe and Wright then returned to the camp, but having noticed no evidence of Burke's return on 21 April, left no further messages or indications and retraced their steps southwards. Brahe arrived in Melbourne late in June 1861 to report on the missing men. On April 23 Burke's trio began the 150-mile (240 km) westward journey to Blanchewater Station, near Mount Hopeless in South Australia, preferring to take this direction over the longer, but known, journey to Menindee. Twice they were forced back to Cooper's Creek due to lack of water to the west. They then remained along the Creek throughout June. On 30 May 1861 Wills had returned to Camp LXV. He found no evidence of Brahe's return in early May, and placed his journals and a new note in the buried cache for fear of accidents, and returned to his companions waiting further along Cooper's Creek. After surviving on ground nardoo, which was slowly poisoning them due to their lack of expertise in its preparation in leaching out the toxins, Wills died alone on the banks of Cooper's Creek on 27 or 28 June. He had insisted that his companions head further down the creek to seek assistance from the Aborigines. A day or two later, Burke also succumbed, having sent King on to look for help. With the assistance of Aborigines, King survived along the watercourse until found on 15 September 1861 by Alfred William Howitt's search party.[1]

When it became known that the well-publicised Burke and Wills expedition had foundered, a number of search parties were quickly organised. Howitt left from Melbourne, John McKinlay from Adelaide, Frederick Walker from Rockhampton, and William Landsborough from Brisbane. Howitt's party, which included Brahe and King, arrived at Camp LXV on 13 September 1861. The Royal Commission was told that they found the depot as Mr Brahe had left it, the plant untouched, and nothing removed of the useless things lying about, but a piece of leather. The party located Wills' remains where his body had been covered by King, some miles downstream of Camp LXV. They buried Wills on 18 September 1861, and inscribed a tree. Field books, notebooks and various small articles were recovered. Three days later and approximately 7 miles (11 km) away, Howitt found Burke's remains near Innamincka Waterhole, 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Innamincka) in South Australia. Burke was buried wrapped in a Union Jack, under a box tree on the south-eastern bank of Cooper's Creek. Howitt blazed this tree at the head of Burke's grave. The Royal Geographical Society, organised to promote exploration, awarded Burke a posthumous RGS Founder's Medal in 1862. Wills was awarded nothing, as the Society's policy was to award only one medal to an exploration party. King received a gold watch, as did McKinlay, Landsborough and Walker for leading their various search parties. These search parties helped open up vast areas of inland Australia for settlement, as a result of the increased knowledge of the country they brought back with them.[1]

A Commission of Enquiry was organised to investigate the circumstances surrounding the deaths of Burke and Wills. The enquiry was held in Melbourne in November and December 1861. The commissioners interviewed thirteen people connected to the expedition, including the only survivor John King, and examined a range of evidence including Wills' journal. The findings of the enquiry were published in a report released at the end of January 1862. While critical of Brahe's decision to leave the depot camp before he was rejoined by Burke, Wills and King, the commission reported that the many of the calamities that befell the expedition might have been averted, including their deaths, if expedition leader Burke kept a regular journal and gave written orders to his men.[1]

In 2010, a student of the University of Queensland, Nick Hadnutt, published his PhD thesis which undertook a detailed analysis of artefacts found at the site when compared with the known dates of the expedition using primary and secondary sources to confirm the authenticity of the site. The thesis concluded that the site was indeed Burke and Wills Camp 46R.[2]

Description

The Burke and Wills Plant Camp site is located on an unnamed creek on Durrie station, approximately two hours drive north of Birdsville. The archaeological record of the Plant Camp has two key components in two different locations. The majority of the European artefacts found to date were located at the terminus of the intermittent unnamed creek and a claypan. Artefacts have been found all along the unnamed creek in varying concentrations. All artefacts are located within the influence of the drainage pattern of the unnamed creek, however artefacts are mostly found on the high points within this local environment. The depth of the artefacts also varies with the majority being found close to the surface or within the top 10–20 millimetres (0.39–0.79 in) of soil.[1]

A number of artefacts have been collected by a number of researchers who have visited the site including canvas/leather sewing kit needles, thrust block, duck bill leather sewing pliers, percussion cap, nipples and bullets consistent with the calibre, vintage and make of weapons taken on the Burke and Wills Expedition. These artefacts have been compared with the "List of Stores III" from the expedition and found to be consistent with goods that were officially supplied.[1]

The remainder of the site consists of two scarred trees located 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) and 2.7 kilometres (1.7 mi) east along the creek from the main artefact concentration. The origin of the scars on these trees remains unknown, but it is possible that these are the remains of blazes associated with the Burke and Wills expedition, providing a visible marker for the location of the Plant Camp for other explorers, or in the case of this expedition, to any potential rescuers.[1]

Evidence of indiscriminate looting of archaeological artefacts is visible throughout the Plant Camp site. More extensive excavations have also been undertaken at the base of the two scarred trees thought to be associated with the Burke and Wills expedition. Both tree locations show evidence of extensive shovel testing or turning of soil - presumably the digger was searching for buried instruments of other artefacts. Ongoing disturbance is a key threat facing Plant Camp as the process of retrieving surface artefacts without sufficient concern for their provenance and the indiscriminate digging up of artefacts removes them from their archaeological context and thus limits our ability to obtain reliable information about the Burke and Wills expedition.[1]

Heritage listing

Burke and Wills "Plant Camp" was listed on the Queensland Heritage Register on 11 December 2008 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The Burke and Wills Plant Camp is significant in demonstrating the evolution or pattern of Queensland's history as evidence of the nineteenth century interest in scientific exploration. The Burke and Wills expedition, and the subsequent search parties sent to find the lost explorers, contributed to the opening up of Queensland and large portions of inland Australia to pastoralism. The process of pastoral expansion commenced soon after the expedition concluded. Expansion into the largely unknown areas of western Queensland and the gulf forever changed these regions.[1]

The Plant Camp is significant as a representation of the past in the present, providing tangible evidence of the first overland north-south crossing of the continent from settled areas in Victoria through Queensland to the Gulf of Carpentaria covering a distance of around 2,800 kilometres (1,700 mi). The place was the final camp established by the explorers and is representative of a key stage in the expedition when Burke and Wills decided to abandon most of their equipment.[1]

The Plant Camp is significant for its potential to contain additional archaeological artefacts associated with the Burke and Wills expedition, particularly equipment associated with Wills' decision to "plant" or bury his astronomical equipment and Burke's order to leave behind everything except food and whatever they could carry on their backs. The Plant Camp has been identified through the presence of archaeological artefacts and two blazed trees situated along an unnamed ephemeral creek line on Durrie Station. Artefacts located to date include percussion caps, nipples, buckles, canvas/leather sewing kit needles, thrust block and duck bill leather sewing pliers a number of the brass fittings, including a clasp, escutcheon, latch and hinge all suggestive of a possible instrument case. These artefacts date to the same period (c. 1850s-1860s) as the Burke and Wills expedition and are consistent with items listed in the detailed "List of Stores III" of goods officially supplied to the expedition.[1]

Plant Camp is significant for its research potential, especially future comparative analysis of archaeological artefacts with others documented at other Burke and Wills campsites. Comparative analysis could provide new and important information on the decisions made by the explorers throughout the expedition, including the rationing of supplies and the value placed on certain objects and items in their possession. For example, scientific analysis may reveal evidence as to why the explorers kept certain scientific instruments and abandoned more practical and useful items which could have increased their chances of success and ultimately survival. Comparative analysis of Plant Camp archaeological artefacts with other early exploration sites across Queensland may also benefit our understanding and knowledge of the conduct of those exploration events.[1]

The Plant Camp has potential to substantiate or challenge documented accounts and myths surrounding the final days of the Burke and Wills expedition. Documentary evidence is limited to that provided in William Wills' journals and to that recorded by the Commission of Enquiry for the expedition held in 1862. Additional archaeological research at the Plant Camp may lead to a greater understanding of the reasons behind the ultimate failure of the expedition and enable a better understanding of the hardships endured by the explorers during the expedition.[1]

The Plant Camp is significant for its special association with prominent Australian explorers Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills, who both died during the return journey in 1861.[1]

References

- "Burke and Wills "Plant Camp" (entry 645622)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- Hadnutt, Nick; School of Social Science, The University of Queensland (25 June 2011), Identifying Camp 46r, the Burke and Wills 'Plant Camp', Australian Archaeological Association Inc, retrieved 10 September 2016CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland heritage register" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 7 July 2014, archived on 8 October 2014). The geo-coordinates were originally computed from the "Queensland heritage register boundaries" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 5 September 2014, archived on 15 October 2014).

This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland heritage register" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 7 July 2014, archived on 8 October 2014). The geo-coordinates were originally computed from the "Queensland heritage register boundaries" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 5 September 2014, archived on 15 October 2014).

Further reading

- Hadnutt, Nicholas (1 October 2010), Identifying camp 46R, the Burke and Wills 'Plant Camp', The University of Queensland, School of Social Science, retrieved 10 September 2016

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burke and Wills Plant Camp. |

- "An Explorer's Plant". The World's News (429). New South Wales, Australia. 5 March 1910. p. 11. Retrieved 10 September 2016 – via National Library of Australia. — Speculations about the whereabouts of the Plant Camp