Burma Corps

The Burma Corps ('Burcorps') was an Army Corps of the Indian Army during World War II. It was formed in Prome, Burma, on 19 March 1942, took part in the retreat through Burma, and was disbanded on arrival in India in May 1942.[1]

| Burma Corps | |

|---|---|

| Active | 19 March – 20 May 1942 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Army Corps |

| Part of | Army in Burma |

| Nickname(s) | Burcorps |

| Engagements | Japanese conquest of Burma Shwedaung Prome Yenangyaung Shwegyin |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Lt-Gen William Slim |

History

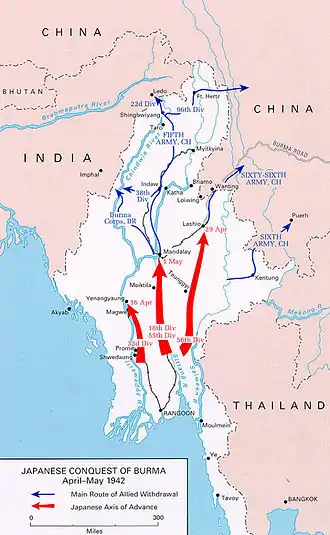

Burcorps was created on 13 March 1942 to take control of the scattered British, Indian and local troops retreating through Burma in the face of a sustained Japanese offensive. The main fighting components of this force were two infantry divisions, 17th Indian Division and 1st Burma Division, but 7th Armoured Brigade Group had recently arrived at Rangoon as reinforcements from the Middle East.[2] Major-General William Slim was brought back from Iraq where he was commanding 10th Indian Infantry Division and promoted to Acting Lieutenant-General to take command of the new corps. He had to improvise a corps staff, including Captain Brian Montgomery, younger brother of General Bernard Montgomery, who filled a number of junior staff roles simultaneously in the early days.[3][4][5][6]

By the time Slim arrived at Magwe on 19 March, Rangoon had already fallen after the Battle of Pegu and Burcorps was retreating to Prome, though 17th Indian Division carried out a number of raids as it withdrew, and the motorised 1st Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment made a surprise attack on Letpadan, temporarily driving the Japanese out. 1st Burma Division in the Sittang Valley retired through the lines of 200th Chinese Division near Taungoo, and then moved west by train to join Burcorps around Prome in the Irrawaddy Valley and cover the Yenangyaung oilfields. On 26 March Burcorps was ordered to stage a demonstration on the Prome front to coincide with a Chinese attack along the Sittang. A striking force was assembled but on 29 March was outflanked and forced to fight its way back through Shwedaung to Prome (the Battle of Shwedaung). Burcorps' HQ was moved back 35 miles (56 km) from Prome to Allanmyo.[7][8][9][10]

Prome came under attack at midnight on 1 & 2 April (the Battle of Prome), and Burcorps was forced to retreat through a series of delaying positions while the Thayetmyo oilfields were destroyed and essential stores evacuated. By 8 April the corps was at the Yin Chaung, defending a 40 miles (64 km) front some 20 miles (32 km) south of the Yenangyaung oilfields. 1st Burma Division was organised as the Corps' Striking Force to hold the western part of this front, while 17th Indian Division at Taungdwingyi was aligned north-south on its eastern flank and 2nd Burma Brigade was further west across the Irrawaddy. Slim moved Burcorps' HQ to Taungdwingyi in an attempt to maintain links with the Chinese. An observation line was established some 16 miles (26 km) to the south of Burcorps' main position, and, patrol clashes on 10 April indicated that the Japanese were moving against the centre of the position. Serious attacks began on 12 April and it became clear that the Japanese were attempting to work around 13th Indian Brigade. Slim ordered a force across the Irrawaddy to Magwe ('Magforce'). By 14 April elements of the corps were surrounded and having to fight their way back to the Yin Chaung, Magwe airfield was being prepared for destruction, and Burcorps was planning to fall back 40 miles (64 km) to the next defensible line on the Pin Chaung.[11][12][13]

On 15 April Slim gave orders for the destruction of the Yenangyaung oilfields; demolition was completed by the afternoon of 16 April, after which the storage tanks were set on fire. 1st Burma Division had attempted to hold on to the Yin Chaung for one more day, and as a result Japanese columns had infiltrated between its scattered units. The Japanese attack came on 16 April and 1st Burma Division resumed its fighting retreat, with Magforce acting as a covering force, but the Japanese cut the line of retreat at Yenangyaun, driving the garrison (1st Gloucesters) southwards. Next day the engineers were used to reinforce 1st Gloucesters and Magforce was given the motor transport to act as an advanced guard for the retreating 1st Burma Division and attempt a roadblock by-pass. On 18 and 19 April Magforce fought its way across the Yenangyaun plain, followed by 1st Burma Division while 7th Armoured Brigade and 38th Chinese Division made diversionary attacks (the Battle of Yenangyaung). 1st Burma Division struggled across the Pin Chaung with the wounded carried on tanks, but most of the transport and artillery had to be destroyed. [14][15][16]

On 21 April the decision was made to evacuate Burma. All the troops would cross the Irrawaddy, then Burcorps would cover the route to India, while 7th Armoured Brigade helped the Chinese. The Irrawaddy crossing was completed by the evening of 30 April, the Ava Bridge was destroyed and Mandalay was abandoned. The fighting portions of Burcorps continued towards the Chindwin River, preceded by an undisciplined mob of refugees and rear-echelon troops. Corps HQ was at Budalin, near Monywa. Once again the retreat was threatened by infiltration, when a Japanese battalion seized Monywa on 1 May. However, the Japanese were unable to exploit this, and Burcorps (including 7th Armoured Brigade) was able to regroup at Ye-U.[17][18][19]

The retreat now turned into a race between Burcorps and the Japanese for Shwegyin before the Monsoon rains broke in mid-May. Japanese air superiority prevented casualties being airlifted out, so 2300 wounded and sick had to be moved along the Ye-U–Shwegyin track, as well as thousands of refugees who were being fed by the army and moved by army transport where possible. From Shwegyin all the troops, motor vehicles and guns had to be ferried across the Chindwin up to Kalewa, while the refugees made their way by a riverside path. The Chindwin was protected from Japanese river craft by a boom manned by the Royal Marines. The ferrying operation was covered by a rearguard formed of 17th Indian Division and 7th Hussars, who manned a series of lay-back positions and flank guards. By 10 May the only troops remaining east of the river were HQ 7th Armoured Brigade, 48th Indian Brigade, and part of 1st Battalion 9th Royal Jats. By now the Japanese were pressing forward, the boom had been destroyed by air attack and Shwegyin was being bombed. On the morning of 10 May the ferrying point came under fire. Counter-attacks failed to dislodge the enemy, and the rearguard had to take to the riverside path after destroying all tanks, vehicles and stores. The gunners fired off as much ammunition as they could before disabling their guns.[20][21][22]

Luckily, the Japanese failed to press the rearguard, and the fighting was over. The troops from Kalewa went to Sittaung by river steamer, arriving on 14 May, and then destroyed the boats before marching to Tamu, where troops of Eastern Army were holding the Indian frontier. 2nd Burma Brigade, which had marched independently along a poor bullock-track to the west, covering 216 miles (348 km) in 14 days, made contact with the Chin Hills Battalion near Kalemyo on 12 May and was evacuated to Tamu by motor transport supplied by IV Corps. 17th Indian Division marched up the Kabaw Valley through the rains and reached Tamu on 17 May. The final rearguard, 63rd Indian Bde, marched in on 19 May. The following day IV Corps assumed operational control of all the units from Burma and Burcorps was disbanded.[23][24][25]

Order of Battle

At its creation on 13 March 1942, Burma Corps comprised the following formations and units:[9][26][27][28]

Staff

- General Officer Commanding (GOC): A/Lt-Gen William Slim

- Commander, Corps Royal Artillery: Brigadier Godfrey de Vere Welchman[29]

- Brigadier, General Staff: H.G. 'Taffy' Davies

- General Staff Officer (GSO3): Walter Walker

Corps Troops

- 7th Armoured Brigade Group[2][30]

- Commander: Temporary Brigadier John Henry Anstice[31]

- 7th Hussars (55 x M3 Stuart tanks)

- 2nd Royal Tank Regiment (55 x Stuarts)

- 414th (Essex Yeomanry) Battery, Royal Horse Artillery (8 x 25-pounder field guns)

- A Battery, 95th Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery (RA) (12 x 2-pounders)

- 1st Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment

- 8th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery, RA[32] (4 x 3-inch guns)

- 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, Indian Artillery (IA) (less one Troop) (12 x Bofors 40 mm guns)

- 1st Field Company, Burma Sappers and Miners

- 17th and 18th Artisan Works Companies

- 6th Pioneer Battalion, Indian Labour Corps[33]

- GOC: Acting Major-General James Bruce Scott[34]

- HQ 27th Indian Mountain Regiment, IA[35]

- 2nd (Derajat) Indian Mountain Battery (4 x 3.7-inch mountain howitzers

- 5th (Bombay) Indian Mountain Battery (4 x 3.7-inch mountain howitzers)

- 23rd Indian Mountain Battery (4 x 3.7-inch mountain howitzers)

- 8th Indian Anti-Tank Battery (4 x 2-pounders)

- HQ Burma Divisional Engineers, Queen Victoria's Own Madras Sappers and Miners (MS&M)[36]

- 50th Field Park Company, MS&M

- 56th Field Company, MS&M (less two sections)

- Malerkotla Field Company, Sappers and Miners (Indian States Forces)[37]

- FF1, FF3, FF4, FF5, Burma Frontier Force (BFF)[lower-alpha 1]

- 1st Burma Infantry Brigade

- 2nd Battalion 7th Rajput Regiment

- 1st Battalion Burma Rifles

- 2nd Battalion Burma Rifles

- 5th Battalion Burma Rifles

- 2nd Burma Infantry Brigade

- 5th Battalion 1st Punjab Regiment

- 7th Battalion Burma Rifles

- FF8

- 13th Indian Infantry Brigade

- 1st Battalion 18th Royal Garhwal Rifles

- GOC: Acting Major-General David Tennant Cowan[39]

- HQ 1st Indian Field Regiment, IA

- HQ 17th Indian Divisional Engineers, MS&M

- 24th Field Company, Royal Bombay Sappers and Miners[40]

- 60th Field Company, MS&M

- 70th Field Company, King George V's Own Bengal Sappers and Miners[41]

- 1st Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment (Motorised reconnaissance unit)

- 5th Battalion Dogra Regiment

- 8th Battalion Burma Rifles

- 16th Indian Infantry Brigade

- 2nd Battalion Duke of Wellington's Regiment

- 1st Battalion 9th Royal Jat Regiment

- 7th Battalion 10th Baluch Regiment

- 4th Battalion 12th Frontier Force Regiment

- 48th Indian Infantry Brigade

- 1st Battalion Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

- Composite Battalion:

- 1st Battalion 3rd Gorkha Rifles

- 2nd Battalion 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles

- 1st Battalion 4th Gorkha Rifles

- Composite Battalion:

- 1st Battalion 7th Gurkha Rifles

- 3rd Battalion 7th Gurkha Rifles

- 63rd Indian Infantry Brigade

- 1st Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers

- 1st Battalion 11th Sikh Regiment

- 2nd Battalion 13th Frontier Force Rifles

- 1st Battalion 10th Gurkha Rifles

Army Troops

- HQ 28th Indian Mountain Regiment, IA (5th, 15th, 28th Indian Mountain batteries absent re-equipping at Mandalay)

- 1st Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Burma Auxiliary Force (BAF)

- 1st Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery, BAF (8 x 3.7-inch guns)

- Detachment, Rangoon Field Brigade, BAF

- Depot, British Infantry

- 10th Battalion Burma Rifles

- Bhamo Battalion, BFF

- Chin Hills Battalion, BFF (less detachment)

- Myitkyina Battalion, BFF

- Northern Shan States Battalion, BFF

- Southern Shan States Battalion, BFF

- Reserve Battalion, BFF

- Kokine Battalion, BFF (less detachments)

- Karen Levies

Line of Communication Troops

- 2nd Indian Anti-Tank Regiment, IA (less two batteries) (8 x 2-pounders)

- 8th Indian Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery, IA

- One Troop 3rd Indian Anti-Aircraft Battery, IA (4 x 40 mm Bofors guns)

- Rangoon Field Brigade, BAF (less detachment)

- 3rd Battalion Burma Rifles

- 4th Battalion Burma Rifles

- 6th Battalion Burma Rifles

- 11th Battalion Burma Rifles, Burma Territorial Force (BTF)

- 12th Battalion Burma Rifles, BTF

- 13th Battalion Burma Rifles, BTF

- 14th Battalion Burma Rifles, BTF

- Tenasserim Battalion, BAF

- Burma Railways Battalion, BAF

- Upper Burma Battalion, BAF

- Mandalay Battalion, BAF

- Detachments Kokine Battalion, BFF

- Detachment Chin Hills Battalion, BFF

- Mounted Infantry Detachment, BFF

- 1st–9th Garrison Companies

There were a number of reallocations of these units within Burcorps during its short existence and several ad hoc forces were also formed for specific operations:[8][9][42]

Striking Force

For counter-attack at Shwedaung 26–29 March[lower-alpha 2]

- HQ 7th Armoured Brigade (Brig J.H. Anstice)

- 7th Hussars

- 414th Battery, RHA

- 14th Field Company, Royal Engineers

- 1st Cameronians

- 2nd Duke of Wellington's

- 1st Gloucesters

- One Company, 1st West Yorkshires

Corps Striking Force

Holding line in front of the Yin Chaung from 6 April

- 1st Burma Division

- 2nd Indian Field Battery

- 27th Mountain Regiment

- HQ, 2nd and 23rd Batteries

- 56th and Malerkotla Field Companies

- 50th Field Park Company

- 48th Indian Brigade

- 1/3rd & 2/5th Gurkha Rifles

- 1/4th Gurkha Rifles

- 1/7th & 3/7th Gurkha Rifles

- 13th Indian Brigade

- 1st Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers

- 2nd KOYLI

- 1/18th Royal Gharwal Rifles

- 1st Burma Brigade

- 2/7th Rajputs

- 1st Burma Rifles

- 5th Burma Rifles

Magforce

Sent to Magwe 12 April

- 5th Mountain Battery

- 1st Cameronians

- 7th Burma Rifles

- 12th Burma Rifles

Footnotes

Notes

- "Burma Corps". OOB.com. Archived from the original on 2007-07-06. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- Playfair, Vol III, p. 125.

- Lewin, pp. 82–5.

- Duncan Anderson, 'Slim', in Keegan (ed.), pp. 298–322.

- Slim at Generals of WWII.

- Woodburn Kirby, Vol II, pp. 147–8.

- Woodburn Kirby, Vol II, pp. 148–9, Map 8.

- Woodburn Kirby, Vol II, pp.157–9

- Farndale, pp. 94–6, Map 20.

- Lewin, pp. 85–8.

- Woodburn Kirby, Vol II, pp. 159–67.

- Farndale, pp. 97–8.

- Lewin, pp. 88–92.

- Woodburn Kirby, Vol II, pp. 167–73.

- Farndale, pp. 98–100.

- Lewin, pp. 92–6.

- Woodburn Kirby, Vol II, pp. 178–84, 200–3, Map 9.

- Farndale, pp. 100–3.

- Lewin, pp. 98–101.

- Woodburn Kirby, Vol II, pp. 205–9, Sketch 8.

- Farndale, pp. 103–5.

- Lewin, pp. 101–3.

- Woodburn Kirby, Vol II, pp. 204, 210.

- Farndale, p. 105.

- Lewin, pp. 103–6.

- Lewin, p. 84.

- Woodburn Kirby, Appendix 13.

- Farndale, Annexes G & J.

- Welchman at Generals of WWII.

- Joslen, pp. 158–9.

- Anstice at Generals of WWII.

- Joslen, p. 521.

- Kempton, p. 332.

- Scott at Generals of WWII.

- Kempton, pp. 38–41.

- Kempton, pp. 60–1.

- Kempton, p. 349.

- Woodburn Kirby, Appendix 1, fn.

- Cowan at Generals of WWII.

- Kempton, p. 65.

- Kempton, p. 56.

- Woodburn Kirby, p. 166, Appendices 15 & 17.

References

- Gen Sir Martin Farndale, History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery: The Far East Theatre 1939–1946, London: Brasseys, 2002, ISBN 1-85753-302-X.

- Lt-Col H.F. Joslen, Orders of Battle, United Kingdom and Colonial Formations and Units in the Second World War, 1939–1945, London: HM Stationery Office, 1960, Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2003, ISBN 1-843424-74-6.

- John Keegan (ed.), Churchill's Generals, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson/New York Grove Weidenfeld, 1991, ISBN 0-8021-1309-5.

- Chris Kempton, A Register of Titles of The Units of the H.E.I.C. and Indian Armies, 1666–1947', (British Empire & Commonwealth Museum Research Paper Number 1), Bristol: British Empire & Commonwealth Museum, 1997, ISBN 0-9530174-0-0.

- Ronald Lewin, Slim:The Standardbearer, London: Leo Cooper, 1976, ISBN, 0-85052-446-6.

- Maj-Gen I.S.O. Playfair, History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series: The Mediterranean and Middle East, Vol III: (September 1941 to September 1942) British Fortunes reach their Lowest Ebb, London: HMSO, 1960 /Uckfield, Naval & Military Press, 2004, ISBN 1-845740-67-X

- Maj-Gen S. Woodburn Kirby, History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series: The War Against Japan Vol II, India's Most Dangerous Hour, London: HM Stationery Office, 1958/Uckfield: Naval & Military, 2004, ISBN 1-845740-61-0.