California montane chaparral and woodlands

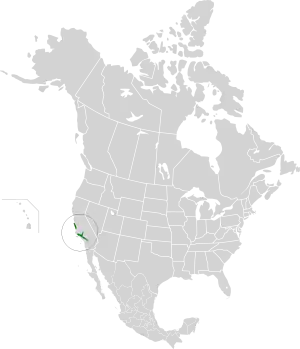

The California montane chaparral and woodlands is an ecoregion defined by the World Wildlife Fund, spanning 7,900 square miles (20,000 km2) of mountains in the Transverse Ranges, Peninsular Ranges, and Coast Ranges of southern and central California. The ecoregion is part of the larger California chaparral and woodlands ecoregion, and belongs to the Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub biome.[3]

| California montane chaparral and woodlands | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Montane chaparral and woodlands of Big Sur | |

| |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Nearctic |

| Biome | Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub |

| Borders | |

| Bird species | 222[1] |

| Mammal species | 78[1] |

| Geography | |

| Area | 20,400 km2 (7,900 sq mi) |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Conservation | |

| Conservation status | Vulnerable[2] |

| Global 200 | Yes |

| Habitat loss | 2.7345%[1] |

| Protected | 63.53%[1] |

Geography and climate

The ecoregion spreads from low foothills up to the highest peaks of the following ranges: San Bernardino Mountains, San Jacinto Mountains, San Gabriel Mountains, Santa Susana Mountains, Santa Monica Mountains, Sierra Pelona Mountains Topatopa Mountains, Tehachapi Mountains, San Rafael Mountains, Santa Ynez Mountains, and the long Santa Lucia Mountains. The region's Mediterranean climate is hot and dry in the summer and cool and wet in the winter.[3]

The wide elevation range and characteristic climate produce a variety of natural communities, from chaparral to mixed evergreen forest to alpine tundra.[3]

Ecology

Flora

Shrublands of Chamise, Manzanita species, and scrub oak tend to dominate the lower elevations of California montane chaparral and woodlands. This ecoregion contains several oak species, including coast live oak, canyon live oak (golden-cup oak), interior live oak, tan oak, and Engelmann oak. It has eight endemic conifer species.

A mosaic of different manzanita species and closed-cone pine forest appears at higher elevations. Bigcone Douglas-fir, Pseudotsuga macrocarpa, is a notable resident of some of these communities. The Mediterranean California Lower Montane Black Oak-Conifer Forest plant community occurs here.

Mixed evergreen forest occurs from 4,500 to 9,500 feet (1,400 to 2,900 m) and includes incense-cedar, foothill pine, sugar pine, white fir, Jeffrey pine, ponderosa pine, and western juniper. Higher elevations to 11,500 feet (3,500 m) support subalpine forests of limber pine, lodgepole pine, and Jeffrey pine.[3]

Hesperoyucca whipplei, colloquially known as Chaparral Yucca, is commonplace throughout the lower elevations of the climate zone.

Fauna

The region contains many species of small vertebrate, including the western fence lizard, white-eared pocket mouse, and several species of kangaroo rat. The monarch butterfly also comes to the area during the winter months and settles around the coast. The area includes some larger predators such as the black bear, mountain lion, bobcat, coyote, and ring-tailed cats.[3]

Conservation status

Approximately 30 percent of California montane chaparral and woodlands remains intact. About 70 percent has been lost due to degradation activities of humans.[4] Montane chaparral is threatened chiefly by development, grazing, logging, conversion to vineyards, too-frequent wildfire, and prescribed fire.[5]

This is an ongoing threat notably in Southern California, but also in its northernmost reaches in Santa Clara County, where population pressure is most intense.

State and federal fish and wildlife agencies, and environmental associations are attempting to conserve the remaining intact ecoregion. The U.S. Forest Service efforts include timber harvest conservation measures in areas with endangered tree species and high endemic and relict species plant communities. Much of the range is within the Los Padres National Forest, Angeles National Forest, and San Bernardino National Forest. Mixed conifer and closed-cone pine forests have been heavily impacted by air pollution. Air quality has improved in southern montane areas around the Los Angeles Basin, since implementation of smog reduction policies and practices in the latter 20th century.[3]

See also

- California chaparral and woodlands ecoregion

- California coastal sage and chaparral — sub-ecoregion

- California interior chaparral and woodlands — sub-ecoregion

- California oak woodland — plant community

- Maritime coast range ponderosa pine forest — plant community

- Mediterranean California Lower Montane Black Oak-Conifer Forest — plant community

- List of ecoregions in the United States (WWF)

References

- Hoekstra, J. M.; Molnar, J. L.; Jennings, M.; Revenga, C.; Spalding, M. D.; Boucher, T. M.; Robertson, J. C.; Heibel, T. J.; Ellison, K. (2010). Molnar, J. L. (ed.). The Atlas of Global Conservation: Changes, Challenges, and Opportunities to Make a Difference. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26256-0.

- "California montane chaparral and woodlands | Ecoregions | WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- "California montane chaparral and woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- Berbach, Chris (2003). "California montane chaparral and woodlands" (PDF).

- Newman, E.A.; et al. (2018). "Chaparral bird community responses to prescribed fire and shrub removal in three management seasons". Journal of Applied Ecology. 55 (4): 1615–1625. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13099. hdl:10150/631176.

External links

Media related to California montane chaparral and woodlands at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to California montane chaparral and woodlands at Wikimedia Commons