Camptodactyly

Camptodactyly is a medical condition that causes one or more fingers to be permanently bent. It involves fixed flexion deformity of the proximal interphalangeal joints.

| Camptodactyly | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

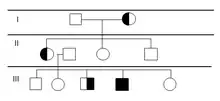

Camptodactyly can be caused by a genetic disorder. In that case, it is an autosomal dominant trait that is known for its incomplete genetic expressivity. This means that when a person has the genes for it, the condition may appear in both hands, one, or neither. A linkage scan proposed that the chromosomal locus of camptodactyly was 3q11.2-q13.12.[1]

Causes

The specific cause of camptodactyly remains unknown, but there are a few deficiencies that lead to the condition. A deficient lumbrical muscle controlling the flexion of the fingers, and abnormalities of the flexor and extensor tendons.[2]

A number of congenital syndromes may also cause camptodactyly:

- Jacobsen syndrome

- Beals syndrome[3]

- Blau syndrome

- Freeman–Sheldon syndrome

- Cerebrohepatorenal syndrome

- Weaver syndrome

- Christian syndrome 1

- Gordon syndrome

- Jacobs arthropathy-camptodactyly syndrome

- Lenz microphthalmia syndrome

- Marshall–Smith–Weaver syndrome

- Oculo-dento-digital syndrome

- Tel Hashomer camptodactyly syndrome

- Toriello–Carey syndrome

- Trisomy 13

- Stuve–Wiedemann syndrome

- Loeys–Dietz syndrome

- Fetal alcohol syndrome

- Fryns syndrome[4]

- Marfan syndrome[5]

- Carnio-carpo-tarsal dysthropy[5]

Genetics

The pattern of inheritance is determined by the phenotypic expression of a gene—which is called expressivity.[6] Camptodactyly can be passed on through generations in various levels of phenotypic expression, which include both or only one hand. This means that the genetic expressivity is incomplete. It can be inherited from either parent.

In most of its cases, camptodactyly occurs sporadically, but it has been found in several studies that it is inherited as an autosomal dominant condition.[1]

Treatment

If a contracture is less than 30 degrees, it may not interfere with normal functioning.[2] The common treatment is splinting and occupational therapy.[7] Surgery is the last option for most cases as the result may not be satisfactory.[8]

Etymology

The name is derived from the ancient Greek words kamptos (bent) and daktylos (finger).

See also

References

- Malik, Sajid; Schott, Jörg; Schiller, Julia; Junge, Anna; Baum, Erika; Koch, Manuela C. (February 2008). "Fifth finger camptodactyly maps to chromosome 3q11.2–q13.12 in a large German kindred". European Journal of Human Genetics. 16 (2): 265–9. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201957. PMID 18000522.

- Kozin, Scott H. (2004). Hand Surgery (1st ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Archived from the original on 2015-01-01. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- Callewaert, Bert L.; Loeys, Bart L.; Ficcadenti, Anna; et al. (March 2009). "Comprehensive clinical and molecular assessment of 32 probands with congenital contractural arachnodactyly: Report of 14 novel mutations and review of the literature". Human Mutation. 30 (3): 334–41. doi:10.1002/humu.20854. PMID 19006240.

- Young, I. D.; Simpson, K.; Winter, R. M. (February 1986). "A case of Fryns syndrome" (PDF). Journal of Medical Genetics. 23 (1): 82–88. doi:10.1136/jmg.23.1.82. PMC 1049547. PMID 3950939. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-12-21.

- Işik, Metin; Doğan, İsmail; Kilinç, Levent; Çalgüneri̇, Meral (2012-03-15). "Familial peripheric polyneuropathy plus camptodactyly; three sisters" (PDF). Turkish Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (in English and Turkish). 58 (1): 72–74. doi:10.4274/tftr.55477. ISSN 2587-0823. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-02-16.

- Cummings, Michael R. (2011). Human Heredity: Principles and Issues (Ninth ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 87, 88. ISBN 978-0538498821. LCCN 2010922222.

- "Camptodactyly Treatments". Boston Children's Hospital. 2013. Archived from the original on 2017-09-05. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- Goldfarb, Charles (2012-03-27). "Congenital Hand and Arm Differences". Washington University in St. Louis. Archived from the original on 2020-08-15. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

External links

Media related to camptodactyly at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to camptodactyly at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of camptodactyly at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of camptodactyly at Wiktionary

| Classification |

|---|