Cape Sable Island

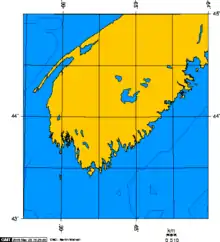

Cape Sable Island, locally referred to as Cape Island, is a small Canadian island at the southernmost point of the Nova Scotia peninsula. It is sometimes confused with Sable Island. Historically, the Argyle, Nova Scotia region was known as Cape Sable and encompassed a much larger area than simply the island it does today. It extended from Cape Negro (Baccaro) through Chebogue.

The island is situated in Shelburne County south of Barrington Head, separated from the mainland by the narrow strait of Barrington Passage, but has been connected since 1949 by a causeway. The largest community on the island is the town of Clark's Harbour. Other communities are listed below. At the extreme southern tip is Cape Sable.

History

Cape Sable Island was inhabited by the Mi'kmaq who knew it as Kespoogwitk meaning "land's end". It was first charted by explorers from Portugal who named it Beusablom, meaning "Sandy Bay".

French Colony

Cape Sable and Cape Negro, Nova Scotia were first settled by the Acadians who migrated from Port Royal, Nova Scotia in 1620.[1] The French governor of Acadia, Charles de la Tour, colonized Cap de Sable giving it the present name, meaning Sandy Cape.[2] La Tour built up a strong post at Cap de Sable beginning in 1623, called Fort Lomeron in honour of David Lomeron who was his agent in France. (The fur trading post called Fort Lomeron was later renamed Fort La Tour although identified as Fort Saint-Louis in the writings of Samuel de Champlain.) Here he carried on a sizable trade in furs with the Mi'kmaq and farmed the land.

During the Anglo-French War (1627–1629), under Charles 1, by 1629 the Kirkes took Quebec City, Sir James Stewart of Killeith, Lord Ochiltree planted a colony on Cape Breton Island at Baleine, and Alexander's son, William Alexander, 1st Earl of Stirling established the first incarnation of "New Scotland" at Port Royal, Nova Scotia. This set of British triumphs in what had otherwise been a disastrous war was not destined to last. Charles 1's haste to make peace with France on the terms most beneficial to him meant that the new North American gains would be bargained away in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1632).[3] There were three battles in Nova Scotia during the colonization of Scots: one at Saint John; another battle at Balene, Cape Breton; and one on Cape Sable Island.

Siege of 1630

In 1629, as a result of these Scottish victories, Cape Sable was the only major French holding in North America.[4] There was a battle between Charles and his father at Fort St. Louis (See National Historic Site - Fort St. Louis), the latter supporting the Scottish who had taken Port Royal. The battle lasted two days. Claude was forced to withdraw in humiliation to Port Royal.[5]

As a result, La Tour appealed to the King of France for assistance and was appointed lieutenant-general in Acadia in 1631.[6]

By 1641, La Tour lost Cape Sable Island, Pentagouet (Castine, Maine), and Port Royal to Governor of Acadia Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay.[7]

La Tour retired to Cap de Sable with his third wife Jeanne Motin, wed in 1653, and died in 1666.[8]

Father Rale's War

During Father Rale's War, there were numerous attacks on New England fishing vessels. As an important landfall and base for seasonal New England fishing vessels working the rich fishing banks of Southwestern Nova Scotia, Cape Sable attracted several waves of pirate attacks in the Golden Age of Piracy. Pirates Ned Low and John Phillips raided fishing vessels off Cape Sable and Phillips met his death off the Cape in 1723.[9]

In 1725 the British signed a treaty (or "agreement") with the Mi'kmaq of Cape Sable and other parts of Nova Scotia but the rights of the Mi'kmaq defined in it to hunt and fish on their lands have often been disputed by the authorities.[10][11]

French and Indian War

The British Conquest of Acadia happened in 1710. Over the next forty-five years the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. During this time period Acadians participated in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.[12] The Acadians and Mi'kmaq from Cape Sable Island raided the Protestants at Lunenburg, Nova Scotia numerous times.

During the French and Indian War, the British sought to neutralize any military threat Acadians posed and to interrupt the vital supply lines Acadians provided to Louisbourg by deporting Acadians from Acadia.[13] In April 1756, Major Jedidiah Preble and his New England troops, on their return to Boston, raided a settlement near Port La Tour and captured 72 men, women and children.[14]

In the late summer of 1758, the British launched three large offensives against the Acadians. One was the St. John River Campaign, another was the Petitcodiac River Campaign, and the other was against the Acadians at Cape Sable Island. Major Henry Fletcher led the 35th Regiment and a company of Joseph Gorham's Rangers to Cape Sable Island. He cordoned off the cape and sent his men through it. One hundred Acadians and Father Jean Baptiste de Gray surrendered, while about 130 Acadians and seven Mi'kmaq escaped. The Acadian prisoners were taken to Georges Island in Halifax Harbour.[15]

En route to the St. John River Campaign in September 1758, Moncton sent Major Roger Morris, in command of two men-of-war and transport ships with 325 soldiers, to deport more Acadians. On October 28, his troops sent the women and children to Georges Island. The men were kept behind and forced to work with troops to destroy their village. On October 31, they were also sent to Halifax.[16] In the spring of 1759, Joseph Gorham and his rangers arrived to take prisoner the remaining 151 Acadians. They reached Georges Island with them on June 29.[17]

New England Planters

Following the Acadian Expulsion in the 1750s, the island was settled by the New England Planters from Cape Cod and nearby Nantucket Island. The waters off southwestern Nova Scotia had been well known to them since the days of French settlement in the early 17th century. While the tides of the Gulf of Maine may have brought a few exploring fishermen from Nantucket to the island, it was an entirely different tide that spawned the eventual permanent English settlement—a political tide.

Many Cape New Englanders took advantage of the offer of 50 acres (200,000 m2) of land to each male adult who would leave his home and live on those vacated lands in Atlantic Canada. Cape Sable Island was well known to Cape Cod fishermen and they moved north in 1760 to take advantage of a new life. The Cape Sable settlement soon became, and remains today, an important base for inshore fisheries. It is famous as the birthplace of the Cape Islander fishing boat, a motor fishing boat which emerged about 1905.[18] Ferry service provided transportation to the island in the early 20th century. A causeway was eventually constructed for pedestrian and automobile traffic, opening on August 5, 1949. Today the lobster fishery is the island's biggest industry.

Raid on Cape Sable Island (1778)

During the American Revolution, on September 4, 1778, the light infantry company of the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants), under the command of Cpt. Ranald MacKinnon, was in the Raid of Cape Sable Island. American Privateers were threatening Cape Sable Island when the 84th Regiment arrived; they surprised the ship in the night and destroyed it. For his aggressive action, MacKinnon was praised highly by Brigadier General Eyre Massey. In response, one of his friends, Cpt. MacDonald, wrote to Major John Small, "McKinnon was embarrassed by the praise of the General and requested it not be inserted in the record since he only did his duty."[19]

Communities of Cape Sable Island

The following communities are included within the Community of Cape Sable Island:[20]

Shipwrecks

Cape Sable is the centre of a busy fishing area and an important landfall for shipping in the Age of Sail. This traffic produced many shipwrecks such as the SS Hungarian in 1862 and the schooner Codseeker in 1877.

Climate

Cape Sable Island has an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb), with significant continental influence. The surrounding waters result in cooler summers, but milder winters, with less snowfall, than the rest of Nova Scotia. Summer temperatures are very low for the latitude, and the climate borders the subpolar oceanic (Köppen Cfc) type. At the peak of summer, in late August and early September, daily average high temperatures barely reach 15°C. Winters are wet and windy, but warm for Atlantic Canada. Snowfall is moderately heavy, but winter brings less snow than in most other locations in Atlantic Canada, which commonly average much more snow per winter season (for example, Sydney, Nova Scotia [283 cm] and St. John's, Newfoundland [335 cm]). Summers on Cape Sable Island are cool with much more stable weather when compared to winters. Due to surrounding cool ocean waters, summer thunderstorms are very rare, but low clouds and fog are common. The strong influence of the Atlantic Ocean also produces exceptionally strong seasonal lag. On average, the coldest month is February, while the warmest month is September, coming in slightly warmer than August, and October is slightly warmer than June.

The island lies in the path of Nor'easters, which reach maximum frequency and intensity in winter, meaning this area's wettest months on average are December and January. Tropical weather systems, including, rarely, hurricanes can occur occasionally, generally entering the area from the south or southwest, with the greatest risk in September and October. Cape Sable Island is also prone to bouts of thick fog. Over the years the Cape's storms, and the close proximity of the island to shipping routes, has led to a substantial number of shipwrecks. The most tragic was the wreck of the SS Hungarian in February 1860 with the loss of over 200 lives. A lighthouse was established at the tip of Cape Sable in the next year.[21]

| Climate data for Cape Sable Island (1948-1986) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.0 (53.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

16.0 (60.8) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

17.2 (63.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

0.7 (33.3) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.7 (42.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

12.0 (53.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

15.1 (59.2) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.6 (29.1) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

12.7 (54.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

1.4 (34.5) |

4.6 (40.3) |

7.3 (45.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

3.3 (37.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.2 (1.0) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−14.5 (5.9) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−19.0 (−2.2) |

−19.0 (−2.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 140.4 (5.53) |

112.7 (4.44) |

104.8 (4.13) |

98.7 (3.89) |

86.4 (3.40) |

76.2 (3.00) |

68.3 (2.69) |

104.6 (4.12) |

73.4 (2.89) |

89.8 (3.54) |

122.2 (4.81) |

139.6 (5.50) |

1,217.1 (47.92) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 86.5 (3.41) |

71.5 (2.81) |

83.5 (3.29) |

94.6 (3.72) |

86.1 (3.39) |

76.2 (3.00) |

68.3 (2.69) |

104.6 (4.12) |

73.4 (2.89) |

89.1 (3.51) |

120.8 (4.76) |

113.3 (4.46) |

1,067.9 (42.04) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 53.9 (21.2) |

41.2 (16.2) |

21.2 (8.3) |

4.2 (1.7) |

0.3 (0.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.7 (0.3) |

1.3 (0.5) |

26.3 (10.4) |

149.0 (58.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 17 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 16 | 138 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 8 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 11 | 112 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 11 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 32 |

| Source: Environment Canada[22] | |||||||||||||

Bird watching

With the ocean lapping on all sides of the island, the climate is maritime - decidedly cool in summer but winters are considerably more moderate than interior parts of the province. The island is a notable birding destination, being an important migratory stopping point for birds such as the Atlantic brant and piping plover. It is this unique climate, its abundant tidal marshes and the island's geographical location on the north-south flight path of numerous migratory water fowl that has given it the international designation as an Important Bird Area. The annual brant geese fly-by during March and April is developing into a local birding event. The tens of thousands of brant make their spectacular fly by at dusk after spending the day feeding in local marshes. They spend the night bobbing in the Atlantic to the east of the island.[23]

See also

References

Texts

- Nicholls, Andrew. A Fleeting Empire: Early Stuart Britain and the Merchant Adventurers to Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. 2010.

Endnotes

- M. A. MacDonald. Fortune and La Tour. Methuen Press. 1983.p.14

- Place Names of Nova Scotia Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management

- Nichols, 2010. p. xix

- Roger Sarty and Doug Knight. Saint John Fortifications: 1630-1956. New Brunswick Military Heritage Series. 2003. p. 18

- Nicholls, 2010, p. 139

- Roger Sarty and Doug Knight. Saint John Fortifications: 1630-1956. Goose Lane Editions. 2003. p. 18

- M. A. MacDonald. La Tour and Fortune. p. 89

- MacBeath, George (1979) [1966]. "Saint-Étienne de La Tour (Turgis), Charles de (1593–1666)". In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Dan Conlin, Pirates of the Atlantic (2009), Halifax: Formac Publishing, p. 34, 44, 52

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-10. Retrieved 2016-02-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- John Grenier, Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press. 2008

- Patterson, Stephen E. (1998). "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61: A Study in Political Interaction". In P.A. Buckner; Gail G. Campbell; David Frank (eds.). The Acadiensis Reader: Atlantic Canada Before Confederation (3rd ed.). Acadiensis Press. pp. 105-106. ISBN 978-0-919107-44-1.

• Patterson, Stephen E. (1994). "1744–1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples". In Phillip Buckner; John G. Reid (eds.). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt15jjfrm. - Winthrop Bell. Foreign Protestants, University of Toronto, 1961, p. 504; Peter Landry. The Lion and the Lily, Trafford Press. 2007.p. 555

- John Grenier, The Far Reaches of Empire, Oklahoma Press. 2008. p. 198

- Marshall, p. 98; see also Bell. Foreign Protestants. p. 512

- Marshall, p. 98; Peter Landry. The Lion and the Lily, Trafford Press. 2007. p. 555

- "Nova Scotia Motorized Fishing Boats" by David A. Walker

- Kim Stacy (1994). No One harms me with impunity - the History, Organization and Biographies of the 84th Highland Regiment (Royal Highland Emigrants) and Young Royal Highlanders during the Revolutionary War 1775-1784. Unpublished manuscript. p. 29

- Nova Scotia Community Counts: Community of Cape Sable Island

- "SS Hungarian" Nova Scotia Museum Marine Heritage Database Archived 2007-07-13 at the Wayback Machine

- "Canadian Climate Normals 1961-1990". Environment Canada. 31 October 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- Important Bird Areas of Canada page for Cape Sable Island Archived March 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine