Captives in American Indian Wars

"Captives in American Indian Wars" refers to combatants and non-combatants captured as prisoners of war, abducted as a means of hostage diplomacy, as countervalue targets, for slavery, and apprehended for purposes of criminal justice by North American indigenous groups and European colonists in the course of conflicts which Europeans and their descendants collectively designated as the American Indian Wars.

The 1677 work The Doings and Sufferings of the Christian Indians documents New England prisoners of war (not, in fact, opposing combatants, but imprisoned Praying Indians) being enslaved and sent to Caribbean destinations.[1][2] Captive indigenous opponents, including women and children, were also sold into slavery at a substantial profit, to be transported to West Indies colonies.[3][4]

Treatment applied to European captives taken in wars or raids in the present-day United States and Canada varied according to the culture of each tribe. Before the arrival of Europeans, Native American and First Nation peoples all across the US and Canada (see Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native Americans in the United States, Indigenous peoples in Canada, and First Nations) had developed customs for dealing with captives. Depending on the cultural region, captives could be killed, tortured, kept alive and assimilated into the tribe, or enslaved. When Native American and the First Nations peoples came into contact with European settlers, they applied longstanding customary traditions for dealing with Native captives to the European newcomers. American and Canadian histories, particularly in the colonial period, includes many examples of captives, and their associated treatment; the American Indian Wars and migrations of the 19th century also resulted in many captives being taken.

Captivity narratives were often written by European-Americans and European-Canadians who were ransomed or escaped from captivity.

Cultural background

In the eastern woodlands cultural area (roughly encompassing the eastern one-half of the United States, and the southern portion of Quebec and Ontario), cultural traditions for dealing with captives predated the arrival of Europeans, and involved either adoption or execution by torture.

Some captives were adopted into their captors' tribe. Adoption frequently involved the captive receiving the name of a deceased member of the captors' tribe, and receiving the deceased's social status (becoming a member of the family of the deceased person).[5] Children and teenage girls seem to have been normally adopted.

Men and women captives[6] as well as teenage boys,[7] would usually face death by ritual torture. The torture had strong sacrificial overtones, usually to the sun.[8] Captives, especially warriors, were expected to show extreme self-control and composure during torture, singing "death songs", bragging of one's courage or deeds in battle, and otherwise showing defiance.[9] The torture was conducted publicly in the captors' village, and the entire population (including children) watched and participated.[10] Common torture techniques included burning the captive, which was done one hot coal at a time, rather than on firewood pyres; beatings with switches or sticks, jabs from sharp sticks as well as genital mutilation and flaying while still alive. Captives' fingernails were ripped out. Their fingers were broken, then twisted and yanked by children. Captives were made to eat pieces of their own flesh, and were scalped and skinned alive. Such was the fate of Jamestown Governor John Ratcliffe. The genitalia of male captives were the focus of considerable attention, culminating with the dissection of the genitals one slice at a time. To make the torture last longer, the Native Americans and the First Nations would revive captives with rest periods during which time they were given food and water. Tortures typically began on the lower limbs, then gradually spread to the arms, then the torso. The Native Americans and the First Nations spoke of "caressing" the captives gently at first, which meant that the initial tortures were designed to cause pain, but only minimal bodily harm. By these means, the execution of a captive, especially an adult male, could take several days and nights.[11]

In contrast to the Eastern Woodlands tribes, peoples of the Northwest Coast (encompassing the coastal regions of Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and southeastern Alaska), enslaved war captives. Slaves were traded and were a valuable commodity. More importantly, slaves were given as gifts during a potlatch ceremony to enhance the prestige of the gift giver. Some scholars believe that slaves performed major economic roles in this region and comprised a permanent social class and a significant proportion of the population, though this is controversial. [12] [13]

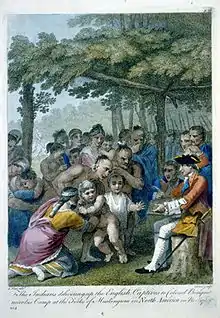

Exchange of captives after 1763 Pontiac's Rebellion

Colonel Henry Bouquet set out from Fort Pitt on October 3, 1764, with 1,150 men. After that, treaties were negotiated at Fort Niagara and Fort Detroit; the Ohio Natives were isolated and, with some exceptions, ready to make peace. In a council which began on 17 October, Bouquet demanded that the Ohio Natives return all captives, including those not yet returned from the French and Indian War. Guyasuta and other leaders reluctantly handed over more than 200 captives, many of whom had been adopted into Native families. Because not all of the captives were present that day, the Natives were compelled to surrender hostages as a guarantee that the other captives would be returned. The Ohio Natives agreed to attend a more formal peace conference with William Johnson, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, which was finalized in July 1765.[14]

References

- Gookin, Daniel (1836) [1677]. . hdl:2027/mdp.39015005075109. OCLC 3976964. archaeologiaame02amer.

But this shows the prudence and fidelity of the Christian Indians; yet notwithstanding all this service they were, with others of our Christian Indians, through the harsh dealings of some English, in a manner constrained, for want of shelter, protection, and encouragement, to fall off to the enemy at Hassanamesit, the story whereof follows in its place; and one of them, viz. Sampson, was slain in fight, by some scouts of our praying Indians, about Watchuset; and the other, Joseph, taken prisoner in Plymouth Colony, and sold for a slave to some merchants at Boston, and sent to Jamaica, but upon the importunity of Mr. Elliot, which the master of the vessel related to him, was brought back again, but not released. His two children taken prisoners with him were redeemed by Mr. Elliot, and afterward his wife, their mother, taken captive, which woman was a sober Christian woman and is employed to teach school among the Indians at Concord, and her children are with her, but her husband held as before, a servant; though several that know the said Joseph and his former carriage, have interceded for his release, but cannot obtain it; some informing authority that he had been active against the English when he was with the enemy.

- Bodge, George Madison (1906). "Capt. Thomas Wheeler and his Men; with Capt. Edward Hutchinson at Brookfield". Soldiers in King Philip's War: Being a Critical Account of that War, with a Concise History of the Indian Wars of New England from 1620–1677 (Third ed.). Boston: The Rockwell and Churchill Press. p. 109. hdl:2027/bc.ark:/13960/t4hn31h3t. LCCN 08003858. OCLC 427544035.

Sampson was killed by some English scouts near Wachuset, and Joseph was captured and sold into slavery in the West Indies.

- Bodge, George Madison (1906). "Appendix A". Soldiers in King Philip's War: Being a Critical Account of that War, with a Concise History of the Indian Wars of New England from 1620–1677 (Third ed.). Boston: The Rockwell and Churchill Press. p. 479. hdl:2027/bc.ark:/13960/t4hn31h3t. LCCN 08003858. OCLC 427544035.

Captives. The following accounts show the harsh custom of the times, and reveal a source of Colonial revenue not open to our country since that day. Account of Captives sold by Mass. Colony. August 24th, 1676. John Hull's Journal page 398.

- Winiarski, Douglas L. (September 2004). Rhoads, Linda Smith (ed.). "A Question of Plain Dealing: Josiah Cotton, Native Christians, and the Quest for Security in Eighteenth-Century Plymouth County" (PDF). The New England Quarterly. 77 (3): 368–413. ISSN 0028-4866. JSTOR 1559824. OCLC 5552741105. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22. Lay summary (2015-02-16).

While Philip and the vast majority of hostile Natives were killed outright during the war or sold into slavery in the West Indies, the friendly Wampanoag at Manomet Ponds retained their lands.

- DeLoria, Phillip, A Companion To American History, 2001, at 157

- Hodge, Frederick W., Handbook of the American Indians North of Mexico, p124

- Jesuit Relations of 1632, Father Paul Le Jeune

- History of the American Indian, La Farge, Oliver, 1966, at 57

- How Early America Sounded, Rath, 2005, at 156

- Indian Wars of New England, by H. M. Sylvester, Vol. I page 45, 1910

- Indians, by Brandon, Wm., 1968, p. 149

- "Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America" by Leland Donald, 1997

- "Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America by Leland Donald" by Christon I. Archer, 1997

- For Bouquet expedition, see Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 233–41; McConnell, A Country Between, 201–05; Dowd, War under Heaven, 162–65.