European colonization of the Americas

Although Europeans had explored and colonized northeastern North America c. 1000 CE, European colonization of the Americas typically refers to the events that took place in the Americas between about 1500 CE and 1800 CE, during the Age of Exploration. During this time period, several European empires–primarily Spain, Portugal, Britain, and France—began to explore and claim the natural resources and human capital of the Americas resulting in the disestablishment of some Indigenous Nations, and the establishment of several settler-colonial states.[1] Some formerly European settler colonies—including New Mexico, Alaska, the Prairies/northern Great Plains, and the "Northwest Territories" in North America; the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the Yucatán Peninsula, and the Darién Gap in Central America; and the northwest Amazon, the central Andes, and the Guianas in South America—remain relatively rural, sparsely populated and Indigenous into the 21st century, however several settler-colonial states, including Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, and the United States grew into settler-colonial empires in their own right.[2] Many of the social structures—including religions, political boundaries, and linguae francae—that predominate the western hemisphere in the 21st century are descendants of the structures established during this period.

| Part of a series on |

| European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

The rapid rate at which Europe grew in wealth and power was unforeseeable in the early 15th century because it had been preoccupied with internal wars and was slowly recovering from the loss of population caused by the Black Death.[3] The grip the Ottoman Empire held on trade routes to Asia prompted western European monarchs to search for alternatives, resulting in the voyages of Christopher Columbus and the accidental re-discovery of the "New World."

Upon signing the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, Portugal and Spain agreed to divide the Earth in two, with Portugal having dominion over non-Christian lands in the eastern half, and Spain over those in the western half. Spanish claims included essentially the entire American continent, however the Treaty of Tordesillas granted the eastern tip of South America to Portugal, where it established Brazil in the early 1500s.

It quickly became clear to other western European powers that they too could benefit from voyages west and by the 1530s, the British and French had begun colonizing the northeast tip of the Americas. Within the century, the Swedish had established New Sweden, the Dutch had established New Netherland, and Denmark–Norway along with the other aforementioned powers had made several claims in the Caribbean, and by the 1700s, Denmark–Norway had revived its former colonies in Greenland, and Russia had begun to explore and claim the Pacific Coast from Alaska to California.

Deadly confrontations became more frequent at the beginning of this period as the Indigenous Nations fought fiercely to preserve their territorial integrity from increasing numbers of European colonizers, as well as from hostile neighbors bearing Eurasian technology. Conflict between the various empires and the Indigenous people was the leading dynamic in the Americas into the 1800s, and although some parts of the continent were gaining independence from Europe by that time, other regions such as California, Patagonia, the Arctic, and the Dakotas experienced little to no colonization at all until the 1800s.

Overview of Western European powers

Norway

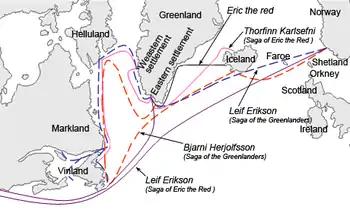

Norwegian explorers are the first known Europeans to set foot on what is now North America. Norwegian journeys to Greenland and Canada are supported by historical and archaeological evidence.[4] Norway established a colony in Greenland in the late 10th century, and lasted until the mid 15th century, with court and parliament assemblies (þing) taking place at Brattahlíð and a bishop located at Garðar.[5] The remains of a settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada, were discovered in 1960 and were dated to around the year 1000 (carbon dating estimate 990–1050 CE).[6] L'Anse aux Meadows is the only site widely accepted as evidence of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact. It was named a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1978.[7] It is also notable for its possible connection with the attempted colony of Vinland, established by Leif Erikson around the same period or, more broadly, with the Norwegian colonization of the Americas.[8]

Spain

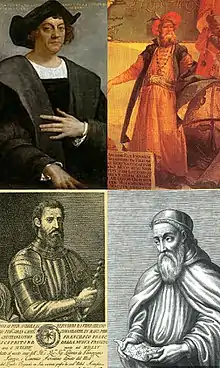

While some Norwegian colonies were established in north eastern North America as early as the 10th century, systematic European colonization began in 1492. A Spanish expedition headed by the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus sailed west to find a new trade route to the Far East but inadvertently landed in what came to be known to Europeans as the "New World". He ran aground on 5 December 1492 on Cat Island (then called Guanahani) in The Bahamas, which the Lucayan people had inhabited since the 9th century. Western European conquest, large-scale exploration and colonization soon followed after the Spanish and Portuguese final reconquest of Iberia in 1492. Columbus's first two voyages (1492–93) reached Hispaniola and various other Caribbean islands, including Puerto Rico and Cuba. In the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, ratified by the Pope, the two kingdoms of Spain and Portugal divided the entire non-European world into two areas of exploration and colonization, with a north to south boundary that cut through the Atlantic Ocean and the eastern part of present-day Brazil. Based on this treaty and on early claims by Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa, discoverer of the Pacific Ocean in 1513, the Spanish conquered large territories in North, Central and South America. They started colonizing the Caribbean, using islands such as Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Hispaniola as bases.

The Spanish had different goals in their exploration of the land than the other European powers. They came to make a fortune and take it back home to Spain while never having the intention to stay and create a new life. They had three goals for exploration: “Conquer, convert, or become rich”.[9] The Spanish justified their claims to the New World based on the Ideals of the Reconquista.[10] They saw their reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula out from the Moor's control as evidence of the “divine help". They believed it to be their duty to save the natives from eternal damnation by converting them to Christianity. In 1431 the first Spaniard had finally become Pope and Spain justified their right to implement Christianity throughout the world.[11]

Over the first century and a half after Columbus's voyages, the native population of the Americas plummeted by an estimated 80% (from around 50 million in 1492 to eight million in 1650),[12] mostly by outbreaks of Old World disease. Some authors have argued this demographic collapse to be the first large-scale act of genocide in the modern era.[13][14] Ten years after Columbus's discovery, the administration of Hispaniola was given to Nicolás de Ovando of the Order of Alcántara, founded during the Reconquista. As in the Iberian Peninsula, the inhabitants of Hispaniola were given new land masters, while religious orders handled the local administration. Progressively the encomienda system, which granted tribute (access to indigenous labor and taxation) to European settlers, was set in place. Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés took over the Aztec Kingdom and from 1519 to 1521, he waged a campaign against the Aztec Empire, ruled by Moctezuma II. The Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, became Mexico City, the chief city of what the Spanish were now calling "New Spain". More than 240,000 Aztecs died during the siege of Tenochtitlan, 100,000 in combat,[15] while 500–1,000 of the Spaniards engaged in the conquest died. Other conquistadors, such as Hernando de Soto, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, and Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, pushed farther north, from Florida, Mexico, and the Caribbean, respectively, in the early 1500s. In 1513, Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama and led the first European expedition to see the Pacific Ocean from the west coast of the New World. In an action with enduring historical import, Balboa claimed the Pacific Ocean and all the lands adjoining it for the Spanish Crown. It was 1517 before another expedition, from Cuba, visited Central America, landing on the coast of Yucatán in search of slaves. To the south, Francisco Pizarro conquered the Inca Empire during the 1530s. As a result, by the mid-16th century, the Spanish Crown had gained control of much of western South America, and southern North America, in addition to its earlier Caribbean territories. The centuries of continuous conflicts between the North American Indians and the Anglo-Americans was less severe than the devastation wrought on the densely populated Mesoamerican, Andean, and Caribbean heartlands.[16] To reward their troops, the Conquistadores often allotted Indian towns to their troops and officers. Black African slaves were introduced to substitute for Native American labor in some locations—including the West Indies, where the indigenous population was nearing extinction on many islands.

On Columbus's return to Hispaniola in 1493, he arrived with 17 ships and 1,200 men but there was little gold left. They "roamed the island in gangs looking for gold, taking women and children as slaves for sex and labor.”[17] In 1500, Columbus wrote that “there are many dealers who go about looking for girls; those from nine to 10 are now in demand.”[17] Due to the shortage in gold, the Spanish established the “Practice of Tribute” under the encomienda system which required every Indian male to turn in a certain amount of gold every ninety days or face death. The reading of The Requerimento before war was both unintelligible to the natives and used as a manipulation tactic. The document stated that the indigenous were subjects of the Spanish Crown and would be tortured if they resisted.[18] As the indigenous population declined, the Europeans abducted people from other islands, like the Lucayan, to labor in the fields and mines of Hispaniola. By the 1600s, the island had been deserted for over a century.[17]

Portugal

Over this same time frame as Spain, Portugal claimed lands in North America (Canada) and colonized much of eastern South America naming it Santa Cruz and Brazil. On behalf of both the Portuguese and Spanish crowns, cartographer Americo Vespuscio explored the American east coast, and published his new book Mundus Novus (New World) in 1502–1503 which disproved the belief that the Americas were the easternmost part of Asia and confirmed that Columbus had reached a set of continents previously unheard of to any Europeans. Cartographers still use a Latinized version of his first name, America, for the two continents. Portuguese conqueror, Pedro Álvares Cabral colonized Brazil while others tried to colonize the eastern coasts of present-day Canada and the River Plate in South America. These explorers include João Vaz Corte-Real in Newfoundland; João Fernandes Lavrador, Gaspar and Miguel Corte-Real and João Álvares Fagundes, in Newfoundland, Greenland, Labrador, and Nova Scotia (from 1498 to 1502, and in 1520).

During this time, the Portuguese gradually switched from an initial plan of establishing trading posts to extensive colonization of what is now Brazil. They imported millions of slaves to run their plantations. The Portuguese and Spanish royal governments expected to rule these settlements and collect at least 20% of all treasure found (the quinto real collected by the Casa de Contratación), in addition to collecting all the taxes they could. By the late 16th century silver from the Americas accounted for one-fifth of the combined total budget of Portugal and Spain.[19] In the 16th century perhaps 240,000 Europeans entered ports in the Americas.[20][21]

France

France founded colonies in the Americas: in eastern North America (which had not been colonized by Spain north of Florida), a number of Caribbean islands (which had often already been conquered by the Spanish or depopulated by disease), and small coastal parts of South America. French explorers included Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524; Jacques Cartier (1491–1557), Henry Hudson (1560s–1611), and Samuel de Champlain (1567–1635), who explored the region of Canada he reestablished as New France.

In the French colonial regions, the focus of economy was on sugar plantations in Caribbean. In Canada the fur trade with the natives was important. About 16,000 French men and women became colonizers. The great majority became subsistence farmers along the St. Lawrence River. With a favorable disease environment and plenty of land and food, their numbers grew exponentially to 65,000 by 1760. Their colony was taken over by Britain in 1760, but social, religious, legal, cultural and economic changes were few in a society that clung tightly to its recently formed traditions.[22][23]

England

British colonization began with North America almost a century after Spain. The relatively late arrival meant that the British could use the other European colonization powers as models for their endeavors.[24] Inspired by the Spanish riches from colonies founded upon the conquest of the Aztecs, Incas, and other large Native American populations in the 16th century, their first attempt at colonization occurred in Roanoke and Newfoundland, although unsuccessful.[25] In 1606, King James I granted a charter with the purpose of discovering the riches at their first permanent settlement in Jamestown, Virginia in 1607. They were sponsored by common stock companies such as the chartered Virginia Company financed by wealthy Englishmen who exaggerated the economic potential of the land.[26]

The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century broke the unity of Western Christendom and led to the formation of numerous new religious sects, which often faced persecution by governmental authorities. In England, many people came to question the organization of the Church of England by the end of the 16th century. One of the primary manifestations of this was the Puritan movement, which sought to "purify" the existing Church of England of its residual Catholic rites. The first of these people, known as the Pilgrims, landed on Plymouth Rock, MA in November 1620. Continuous waves of repression led to the migration of about 20,000 Puritans to New England between 1629 and 1642, where they founded multiple colonies. Later in the century, the new Pennsylvania colony was given to William Penn in settlement of a debt the king owed his father. Its government was established by William Penn in about 1682 to become primarily a refuge for persecuted English Quakers; but others were welcomed. Baptists, German and Swiss Protestants and Anabaptists also flocked to Pennsylvania. The lure of cheap land, religious freedom and the right to improve themselves with their own hand was very attractive.[27]

Mainly due to discrimination, there was often a separation between English colonial communities and indigenous communities. The Europeans viewed the natives as savages who were not worthy of participating in what they considered civilized society. The native people of North America did not die out nearly as rapidly nor as greatly as those in Central and South America due in part to their exclusion from British society. The indigenous people continued to be stripped of their native lands and were pushed further out west.[28] The English eventually went on to control much of Eastern North America, the Caribbean, and parts of South America. They also gained Florida and Quebec in the French and Indian War.

John Smith convinced the colonists of Jamestown that searching for gold was not taking care of their immediate needs for food and shelter. The lack of food security leading to extremely high mortality rate was quite distressing and cause for despair among the colonists. To support the colony, numerous supply missions were organized. Tobacco later became a cash crop, with the work of John Rolfe and others, for export and the sustaining economic driver of Virginia and the neighboring colony of Maryland. Plantation agriculture was a primary aspect of the colonies in the southeast US and in the Caribbean. They heavily relied on African slave labor to sustain their economic pursuits.[9]

From the beginning of Virginia's settlements in 1587 until the 1680s, the main source of labor and a large portion of the immigrants were indentured servants looking for new life in the overseas colonies. During the 17th century, indentured servants constituted three-quarters of all European immigrants to the Chesapeake region. Most of the indentured servants were teenagers from England with poor economic prospects at home. Their fathers signed the papers that gave them free passage to America and an unpaid job until they became of age. They were given food, clothing, housing and taught farming or household skills. American landowners were in need of laborers and were willing to pay for a laborer's passage to America if they served them for several years. By selling passage for five to seven years worth of work, they could then start on their own in America.[29] Many of the migrants from England died in the first few years.[26]

Economic advantage also prompted the Darien Scheme, an ill-fated venture by the Kingdom of Scotland to settle the Isthmus of Panama in the late 1690s. The Darien Scheme aimed to control trade through that part of the world and thereby promote Scotland into a world trading power. However, it was doomed by poor planning, short provisions, weak leadership, lack of demand for trade goods, and devastating disease.[30] The failure of the Darien Scheme was one of the factors that led the Kingdom of Scotland into the Act of Union 1707 with the Kingdom of England creating the united Kingdom of Great Britain and giving Scotland commercial access to English, now British, colonies.[31]

Christian conversion

When Pope Alexander VI issued the Inter caetera bull in May 1493 granting the new lands to the Kingdom of Spain, he requested in exchange an evangelization of the people. During Columbus's second voyage, Benedictine monks accompanied him, along with twelve other priests. Through a practice called the Mission System, supervised communities were established in frontier areas so that Spanish priests could preach the gospel to the indigenous population. These missions were established throughout the Spanish colonies which extended from the southwestern portions of current-day United States through Mexico and to Argentina and Chile. In the 1530s, the Spanish Roman Catholic Church, needing the natives' labor and cooperation, evangelized in Quechua, Nahuatl, Guaraní and other Native American languages. This contributed to the expansion of indigenous languages, including the establishment of tribal writing systems. One of the first primitive schools for Native Americans was founded by Fray Pedro de Gante in 1523.

As slavery was prohibited between Christians and could only be imposed in non-Christian prisoners of war or on men already sold as slaves, the debate on Christianization was particularly acute during the 16th century. Later, two Dominican priests, Bartolomé de Las Casas and the philosopher Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, held the Valladolid debate, with the former arguing that Native Americans were endowed with souls like all other human beings, while the latter argued to the contrary to justify their enslavement. In 1537, the papal bull Sublimis Deus definitively recognized that Native Americans possessed souls, thus prohibiting their enslavement, without putting an end to the debate. Some claimed that a native who had rebelled and then been captured could be enslaved nonetheless. The process of Christianization was at first violent: when the first Franciscans arrived in Mexico in 1524, they burned the places dedicated to pagan cult, alienating much of the local population.[32] Consequently, the indigenous were forced to denounce their intergenerational tribal beliefs and subjugate their history.

Slavery

.jpg.webp)

The practice of slavery was not uncommon in native society prior to the arrival of the Europeans. Captured members of rival tribes were often used as slaves and/or for human sacrifice. But with the arrival of white colonists, Indian slavery "became commodified, expanded in unexpected ways, and came to resemble the kinds of human trafficking that are recognizable to us today".[33]

While disease was the main killer of the Indians, the practice of slavery was also significant contributor to the indigenous death toll.[11] With the arrival of other European colonial powers, the enslavement of native populations increased as these empires lacked legislation against slavery until decades later. It is estimated that from Columbus's arrival to the end of the nineteenth century between 2.5 and 5 million Native Americans were forced into slavery. Indigenous men, women, and children were often forced into labor in sparsely populated frontier settings, in the household, or in the toxic gold and silver mines.[34] To further extract as much gold as possible, the Europeans required all males above the age of 13 to trade gold as tribute. This practice was known as the encomienda system and granted free native labor to the Spaniards. Based upon the practice of exacting tribute from Muslims and Jews during the Reconquista, the Spanish Crown granted a number of native laborers to an encomendero, who was usually a conquistador or other prominent Spanish male. Under the grant, they were bound to both protecting the natives and converting them to Christianity. In exchange for their forced conversion to Christianity, the natives had to pay tributes in the form of gold, agricultural products, and labor. The Spanish crown saw the severe abuses going on and tried to terminate the system through the Laws of Burgos(1512–13) and the New Laws of the Indies (1542). However, the encomenderos refused to comply with the new measures and the indigenous people continued to be exploited. Eventually, the encomienda system was replaced by the repartimiento system which was not abolished until the late 18th century.[35]

In the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the Pueblo tribe led an uprising that resulted in the death of 400 Spanish colonizers and the reclaiming of indigenous land. Andrés Resendez argues this to be "the greatest insurrection against the other slavery".[33] Resendez also argues that the perpetrators of native slavery were not always European colonists. He claims that the rise of powerful Indian tribes in what is now the American Southwest, such as the Comanche, led to indigenous control of the Native American slave trade by the early 1700s. The arrival of European settlers in the West increased the slave traffic by the nineteenth century.[34] There is debate over whether the indigenous population of the Americas suffered a greater demographic decline than the African continent, despite the latter having lost roughly 12.5 million individuals to the transatlantic slave trade.[33]

By the 18th century, the overwhelming number of black slaves was such that Amerindian slavery was less commonly used. Africans, who were taken aboard slave ships to the Americas, were primarily obtained from their African homelands by coastal tribes who captured and sold them. Europeans traded for slaves with the slave capturers of the local native African tribes in exchange for rum, guns, gunpowder, and other manufactures. The total slave trade to islands in the Caribbean, Brazil, the Portuguese, Spanish, French, Dutch, and British Empires is estimated to have involved 12 million Africans.[36][37] The vast majority of these slaves went to sugar colonies in the Caribbean and to Brazil, where life expectancy was short and the numbers had to be continually replenished. At most about 600,000 African slaves were imported into the United States, or 5% of the 12 million slaves brought across from Africa.[38]

Even though slavery went against the mission of the Catholic Church, the colonizers justified the practice through the belts of latitude theory, supported by Aristotle and Ptolemy. In this perspective, belts of latitude wrapped around the earth and corresponded with specific human traits. The peoples from the "cold zone" in Northern Europe were "of lesser prudence", while those of the "hot zone" in sub-Sahara Africa were intelligent but "weaker and less spirited".[33] According to the theory, those of the "temperate zone" across the Mediterranean reflected an ideal balance of strength and prudence. Such ideas about latitude and character justified a natural human hierarchy.[33]

During the Gold Rush of the 1800s, Indian enslavement flourished. American landowner, John Bidwell, coerced Indian children to work on his ranch by scaring them with tales of man-eating grizzly bears. He justified his protection and offering of food and clothing as fair payment for indigenous labor. Captain John Sutter paid the Indian slaves with metal disks that were punched with star-shaped holes to keep track of how much work they did. Two weeks of work meant they could receive a cotton shirt or a pair of pants. Andrew Kelsey organized the enslavement of five hundred Pomo Indians, where they flogged and shot these people for entertainment. They also raped young Indian women. In 1849, the Indians finally rebelled and murdered Kelsey in what became known as the Bloody Island Massacre. Other laws legalized a peonage system that allowed trial and punishment of any Indian who was traveling without a proper certificate of employment. These documents listed the "advanced wages" as a debt to be repaid before the Indian could be free to leave. This system allowed ranchers to control the migration of Indians and subject them to the labor draft. The Indian Act of 1850 legalized all types of exploitation and atrocities of indigenous people, including the "apprenticeship" of Indian minors which in practice gave the petitioner control of both the child and his/her earnings. Thus, the establishment of encomiendas, repartimientos, selling of convict labor, and debt peonage replaced formal slavery by instituting informal labor coercive practices that were nearly impossible to track, thus enabling the slave trade to continue.[33]

Religious immigration

Roman Catholics were the first major religious group to immigrate to the New World, as settlers in the colonies of Portugal and Spain, and later, France, belonged to that faith. English and Dutch colonies, on the other hand, tended to be more religiously diverse. Settlers to these colonies included Anglicans, Dutch Calvinists, English Puritans and other nonconformists, English Catholics, Scottish Presbyterians, French Huguenots, German and Swedish Lutherans, as well as Jews, Quakers, Mennonites, Amish, and Moravians.[39]

Disease and indigenous population loss

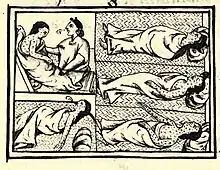

Nahua suffering from smallpox

The European lifestyle included a long history of sharing close quarters with domesticated animals such as cows, pigs, sheep, goats, horses, dogs and various domesticated fowl, from which many diseases originally stemmed. In contrast to the indigenous people, the Europeans had developed a richer endowment of antibodies.[40] The large-scale contact with Europeans after 1492 introduced Eurasian germs to the indigenous people of the Americas.

Epidemics of smallpox (1518, 1521, 1525, 1558, 1589), typhus (1546), influenza (1558), diphtheria (1614) and measles (1618) swept the Americas subsequent to European contact,[41][42] killing between 10 million and 100 million[43] people, up to 95% of the indigenous population of the Americas.[44] The cultural and political instability attending these losses appears to have been of substantial aid in the efforts of various colonists in New England and Massachusetts to acquire control over the great wealth in land and resources of which indigenous societies had customarily made use.[45]

Such diseases yielded human mortality of an unquestionably enormous gravity and scale – and this has profoundly confused efforts to determine its full extent with any true precision. Estimates of the pre-Columbian population of the Americas vary tremendously.

Others have argued that significant variations in population size over pre-Columbian history are reason to view higher-end estimates with caution. Such estimates may reflect historical population maxima, while indigenous populations may have been at a level somewhat below these maxima or in a moment of decline in the period just prior to contact with Europeans. Indigenous populations hit their ultimate lows in most areas of the Americas in the early 20th century; in a number of cases, growth has returned.[46]

According to scientists from University College London, the colonization of the Americas by Europeans killed so much of the indigenous population that it resulted in climate change and global cooling.[47][48][49] Some contemporary scholars also attribute significant indigenous population losses in the Caribbean to the widespread practice of slavery and deadly forced labor in gold and silver mines.[50][51][52] Historian, Andrés Reséndez, supports this claim and argues that indigenous populations were smaller previous estimations and “a nexus of slavery, overwork and famine killed more Indians in the Caribbean than smallpox, influenza and malaria.” [17]

Impact of colonial land ownership on long-term development

Eventually, most of the Western Hemisphere came under the control of Western European governments, leading to changes to its landscape, population, and plant and animal life. In the 19th century over 50 million people left Western Europe for the Americas.[53] The post-1492 era is known as the period of the Columbian Exchange, a dramatically widespread exchange of animals, plants, culture, human populations (including slaves), ideas, and communicable disease between the American and Afro-Eurasian hemispheres following Columbus's voyages to the Americas.

Most scholars writing at the end of the 19th century estimated that the pre-Columbian population was as low as 10 million; by the end of the 20th century most scholars gravitated to a middle estimate of around 50 million, with some historians arguing for an estimate of 100 million or more.[54] A recent estimate is that there were about 60.5 million people living in the Americas immediately before depopulation,[55] of which 90 per cent, mostly in Central and South America, perished from wave after wave of disease, along with war and slavery playing their part.[56][51]

Geographic differences between the colonies played a large determinant in the types of political and economic systems that later developed. In their paper on institutions and long-run growth, economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson argue that certain natural endowments gave rise to distinct colonial policies promoting either smallholder or coerced labor production.[57] Densely settled populations, for example, were more easily exploitable and profitable as slave labor. In these regions, landowning elites were economically incentivized to develop forced labor arrangements such as the Peru mit'a system or Argentinian latifundias without regard for democratic norms. French and British colonial leaders, conversely, were incentivized to develop capitalist markets, property rights, and democratic institutions in response to natural environments that supported smallholder production over forced labor.

James Mahoney, a professor at Northwestern University, proposes that colonial policy choices made at critical junctures regarding land ownership in coffee-rich Central America fostered enduring path dependent institutions.[58] Coffee economies in Guatemala and El Salvador, for example, were centralized around large plantations that operated under coercive labor systems. By the 19th century, their political structures were largely authoritarian and militarized. In Colombia and Costa Rica, conversely, liberal reforms were enacted at critical junctures to expand commercial agriculture, and they ultimately raised the bargaining power of the middle class. Both nations eventually developed more democratic and egalitarian institutions than their highly concentrated landowning counterparts.

Colonization and race

Throughout the South American hemisphere, there were three large regional sources of populations: Native Americans, arriving Europeans, and forcibly transported Africans. The mixture of these cultures impacted the ethnic makeup that predominates in the hemisphere's largely independent states today. The term to describe someone of mixed European and indigenous ancestry is mestizo while the term to describe someone of mixed European and African ancestry is mulatto. The mestizo and mulatto population are specific to Iberian influenced current day Latin America because the conquistadors had (often forced) sexual relations with the indigenous and African women.[59] The social interaction of these three groups of people inspired the creation of a caste system based on skin tone. The hierarchy centered around those with the lightest skin tone and ordered from highest to lowest was the Spanish, mestizo, indigenous, mulatto, then African.[11]

Unlike the Iberians, the British men came with families with whom they planned to permanently live in what is now North America.[25] Because the British colonizers' wives were present, the British men rarely had sexual relations with the native women. While the mestizo and mulatto population make up the majority of people in Latin America today, there is only a small mestizo population in present-day North America (excluding Central America).[24]

List of European colonies in the Americas

.jpg.webp)

There were at least a dozen European countries involved in the colonization of the Americas. The following list indicates those countries and the Western Hemisphere territories they worked to control.[60]

British and (before 1707) English

- British America (1607–1783)

- Thirteen Colonies (1607–1783)

- Rupert's Land (1670–1870)

- British Columbia (1793–1871)

- British North America (1783–1907)

- British West Indies

- Belize

Courland (indirectly part of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth)

- New Courland (Tobago) (1654–1689); Courland is now part of Latvia

Danish

- Dano-Norwegian West Indies (1754–1814)

- Danish West Indies (1814–1917)

- Dano-Norwegian North Greenland (1721–1814)

- Dano-Norwegian South Greenland (1728?–1814)

- Greenland (1814–1953)

Dutch

- New Netherland (1609–1667)

- Essequibo (1616–1815)

- Dutch Virgin Islands (1625–1680)

- Berbice (1627–1815)

- New Walcheren (1628–1677)

- Dutch Brazil (1630–1654)

- Pomeroon (1650–1689)

- Cayenne (1658–1664)

- Demerara (1745–1815)

- Suriname (1667–1954) (Remained within the Kingdom of the Netherlands until 1975 as a constituent state)

- Curaçao and Dependencies (1634–1954) (Aruba and Curaçao are still in the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Bonaire; 1634–present)

- Sint Eustatius and Dependencies (1636–1954) (Sint Maarten is still in the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Sint Eustatius and Saba; 1636–present)

French

- New France (1604–1763)

- Acadia (1604–1713)

- Canada (1608–1763)

- Louisiana (1699–1763, 1800–1803)

- Newfoundland (1662–1713)

- Île Royale (1713–1763)

- French Guiana (1763–present)

- French West Indies

Fort Lachine in New France, 1689

Fort Lachine in New France, 1689 - Saint-Domingue (1659–1804, now Haiti)

- Tobago

- Virgin Islands

- France Antarctique (1555–1567)

- Equinoctial France (1612–1615)

- French Florida (1562–1565)

Knights of Malta

- Saint Barthélemy (1651–1665)

- Saint Christopher (1651–1665)

- Saint Croix (1651–1665)

- Saint Martin (1651–1665)

Norwegian

- Greenland (986–1408[61])

- Dano-Norwegian South Greenland (1728?–1814)

- Dano-Norwegian North Greenland (1721–1814)

- Dano-Norwegian West Indies (1754–1814)

- Cooper Island (1844–1905)

- Sverdrup Islands (1898–1930)

- Erik the Red's Land (1931–1933)

Portuguese

- Colonial Brazil (1500–1815) became a Kingdom, United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves.

- Terra do Labrador (1499/1500–?) Claimed region (sporadically settled).

- Land of the Corte-Real, also known as Terra Nova dos Bacalhaus (Land of Codfish) – Terra Nova (Newfoundland) (1501–?) Claimed region (sporadically settled).

- Portugal Cove-St. Philip's (1501–1696)

- Nova Scotia (1519?–1520s?) Claimed region (sporadically settled).

- Barbados (c.1536–1620)

- Colonia do Sacramento (1680–1705/1714–1762/1763–1777 (1811–1817))

- Cisplatina (1811–1822, now Uruguay)

- French Guiana (1809–1817)

Russian

- Russian America (Alaska) (1799–1867)

- Fort Ross (Sonoma County, California)

Scottish

- Nova Scotia (1622–1632)

- Darien Scheme on the Isthmus of Panama (1698–1700)

- Stuarts Town, Carolina (1684–1686)

Spanish

- Cuba (until 1898)

- Viceroyalty of New Granada (1717–1819)

- Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535–1821)

- Louisiana (New Spain)

- Spanish Florida (1565-1763)

- Spanish Texas (1716-1802)

- Viceroyalty of Peru (1542–1824)

- Captaincy General of Chile

- Puerto Rico (1493–1898)

- Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata (1776–1814)

- Hispaniola (1493–1865); the island currently comprising Haiti and the Dominican Republic, under Spanish rule in whole or in part from 1492 to 1865.

Swedish

- New Sweden (1638–1655)

- Saint Barthélemy (1784–1878)

- Guadeloupe (1813–1814)

Failed attempts

Exhibitions and collections

In 2007, the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History and the Virginia Historical Society (VHS) co-organized a traveling exhibition to recount the strategic alliances and violent conflict between European empires (English, Spanish, French) and the Native people living in North America. The exhibition was presented in three languages and with multiple perspectives. Artifacts on display included rare surviving Native and European artifacts, maps, documents, and ceremonial objects from museums and royal collections on both sides of the Atlantic. The exhibition opened in Richmond, Virginia on March 17, 2007, and closed at the Smithsonian International Gallery on October 31, 2009.

The related online exhibition explores the international origins of the societies of Canada and the United States and commemorates the 400th anniversary of three lasting settlements in Jamestown (1607), Quebec City (1608), and Santa Fe (1609). The site is accessible in three languages.[62]

See also

- Martín de Argüelles

- Atlantic history

- Atlantic world

- Bandeirantes

- Chronology of the colonization of North America

- Colonial history of the United States

- Colonialism

- Columbian Exchange

- Conquistador

- Hernán Cortés

- European colonization of the Southern United States

- Former colonies and territories in Canada

- History of the west coast of North America

- Indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Influx of disease in the Caribbean

- Imperialism

- List of North American cities founded in chronological order

- Norse colonization of the Americas

- Francisco Pizarro

- Population history of indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Portuguese Empire

- Romanus Pontifex and Inter caetera

- Settler colonialism

- Spanish conquest of Yucatán

- Spanish Empire

- Thirteen Colonies, which became the United States in 1776

- Timeline of the European colonization of North America

- Timeline of imperialism#Colonization of North America

- Treaty of Alcáçovas

- Treaty of Tordesillas

- Francisco Vásquez de Coronado

Notes

- Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery : the Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America / Andrés Reséndez. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016. Print.

- "Imperialism at Home and Abroad". saylordotorg.github.io. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- Taylor, Alan (2001). American Colonies. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-200210-0.

- T. Douglas Price (2015). Ancient Scandinavia: An Archaeological History from the First Humans to the Vikings. Oxford University Press. p. 321. ISBN 978-0-19-023198-9.

- S.A. Wurm; Peter Mühlhäusler; Darrell T. Tyron (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. Walter de Gruyter. p. 1048. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.

- Linda S. Cordell; Kent Lightfoot; Francis McManamon; George Milner (2008). Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 82–. ISBN 978-0-313-02189-3.

- John Logan Allen (2007). North American Exploration. U of Nebraska Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8032-1015-8.

- Axel Kristinsson (2010). Expansions: Competition and Conquest in Europe Since the Bronze Age. ReykjavíkurAkademían. p. 216. ISBN 978-9979-9922-1-9.

- Hair, Chris. "Differences Between British and Spanish Colonization of North America: Analysis of J.H. Elliot's Empire's of the Atlantic World." The American West: An Eclectic History. N.p., 20 Nov. 2012. Web. 17 Mar. 2015. <<http://theamericanwestaneclectichistory.blogspot.com/2012/11/differences-between-british-and-spanish.html>.>.

- Seed, Patricia. American Pentimento [electronic Resource] : The Invention of Indians and the Pursuit of Riches / Patricia Seed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001. Print.

- Bonch-Bruevich, Xenia. “Ideologies of the Spanish Reconquest and Isidore's Political Thought.” Mediterranean Studies, vol. 17, 2008, pp. 27–45. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41167390. Accessed 12 Nov. 2020.

- "La catastrophe démographique" (The Demographic Catastrophe) in L'Histoire n°322, July–August 2007, p. 17

- Forsythe, David P. (2009). Encyclopedia of Human Rights, Volume 4. Oxford University Press. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-19-533402-9.

- David E. Stannard (1993-11-18). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

- Russell, Philip (2015). The Essential History of Mexico: From Pre-Conquest to Present. ISBN 978-1-135-01721-7.

- White, Matthew (2011). Atrocities: The 100 Deadliest Episodes in Human History. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-08330-9.

- Brockell, Gillian. "Here are the indigenous people Christopher Columbus and his men could not annihilate". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- Seed, Patricia. Ceremonies of possession in Europe's conquest of the New World, 1492-1640. United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- "Spain". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28.

- "The Columbian Mosaic in Colonial America" by James Axtell Archived March 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "The Spanish Colonial System, 1550–1800. Population Development". Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- W.J. Eccles, The Canadian Frontier, 1534–1760 (1969)

- Leslie Choquette, Frenchmen into peasants: modernity and tradition in the peopling of French Canada (1997)

- Haring, Clarence H. The Spanish Empire in America. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985. Print.

- Society, National Geographic (2020-05-19). "Motivations for Colonization". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2020-10-13.

- Taylor, Alan (2001). American Colonies. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-200210-0.

- John Chester Miller (1966). The First Frontier: Life in Colonial America. University Press of America. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-8191-4977-0.

- "Native Americans, Treatment of (Spain vs England)." Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History. Ed. Thomas Carson and Mary Bonk. Detroit: Gale, 1999. N. pag. World History in Context. Web. 30 Mar. 2015.

- Barker, Deanna (10 March 2004). "Indentured Servitude in Colonial America". National Association for Interpretation, Cultural Interpretation and Living History Section. Archived from the original on October 22, 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- John Prebble, Darien: the Scottish Dream of Empire (2000)

- Brocklehurst, "The Banker who Led Scotland to Disaster".

- "Espagnols-Indiens: le choc des civilisations", in L'Histoire n°322, July–August 2007, pp. 14–21 (interview with Christian Duverger, teacher at the EHESS)

- Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery : the Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America / Andrés Reséndez. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016. Print.

- Waite, Kevin. "The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America." The Journal of Civil War Era, vol. 7, no. 3, 2017, p. 473+. Gale Academic OneFile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A502506898/AONE?u=tel_a_vanderbilt&sid=AONE&xid=0e6d28ed. Accessed 17 Oct. 2020.

- "encomienda | Definition & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- Segal, Ronald (1995). The Black Diaspora: Five Centuries of the Black Experience Outside Africa. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-374-11396-4.

It is now estimated that 11,863,000 slaves were shipped across the Atlantic. [Note in original: Paul E. Lovejoy, "The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on Africa: A Review of the Literature," in Journal of African History 30 (1989), p. 368.] ... It is widely conceded that further revisions are more likely to be upward than downward.

- "Quick guide: The slave trade". bbc.co.uk. March 15, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- Stephen D. Behrendt, David Richardson, and David Eltis, W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African-American Research, Harvard University. Based on "records for 27,233 voyages that set out to obtain slaves for the Americas". Stephen Behrendt (1999). "Transatlantic Slave Trade". Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. New York: Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00071-5.

- Patricia U. Bonomi, Under the cope of heaven: Religion, society, and politics in Colonial America (2003).

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- American Indian Epidemics Archived February 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "Smallpox: Eradicating the Scourge". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- Mann, Charles C. (2005). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Knopf. pp. 106–109. ISBN 978-1-4000-3205-1.

- "The Story Of... Smallpox". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (ISBN 1-4000-4006-X), Charles C. Mann, Knopf, 2005.

- Thornton, pp. xvii, 36.

- Amos, Jonathan (February 2, 2019). "America colonisation 'cooled Earth's climate'". BBC. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- Kent, Lauren (February 1, 2019). "European colonizers killed so many Native Americans that it changed the global climate, researchers say". CNN. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- Koch, Alexander; Brierley, Chris; Maslin, Mark M.; Lewis, Simon L. (2019). "Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492". Quaternary Science Reviews. 207: 13–36. Bibcode:2019QSRv..207...13K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004.

- Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 17. ISBN 978-0547640983.

- Treuer, David (May 13, 2016). "The new book 'The Other Slavery' will make you rethink American history". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Hickel, Jason (2018). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. Windmill Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1786090034.

- David Eltis Economic Growth and the Ending of the Transatlantic slave trade

- Taylor, Alan (2002). American colonies; Volume 1 of The Penguin history of the United States, History of the United States Series. Penguin. p. 40. ISBN 978-0142002100. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- Koch, Alexander; Brierley, Chris; Maslin, Mark M.; Lewis, Simon L. (2019). "Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492". Quaternary Science Reviews. 207: 13–36. Bibcode:2019QSRv..207...13K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004.

- Maslin, Mark; Lewis, Simon (June 25, 2020). "Why the Anthropocene began with European colonisation, mass slavery and the 'great dying' of the 16th century". The Conversation. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson, “Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth,” Handbook of Economic Growth 1: 385–472. 2005.

- James Mahoney, “Path-Dependent Explanations of Regime Change: Central America in Comparative Perspective.” Studies in Comparative International Development, 2001.

- Manning, Patrick. Migration in World History [electronic Resource]. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2012. Print.

- Note that throughout this period, certain countries in Europe became united and also disunited (e.g.: Denmark/Norway, England/Scotland, Spain/Netherlands).

- Dale Mackenzie Brown (February 28, 2000). "The Fate of Greenland's Vikings". Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "Jamestown, Québec, Santa Fe: Three North American Beginnings". National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

Bibliography

- Bailyn, Bernard, ed. Atlantic History: Concept and Contours (Harvard UP, 2005)

- Bannon, John Francis. History of the Americas (2 vols. 1952), older textbook

- Bolton, Herbert E. "The Epic of Greater America," American Historical Review 38, no. 3 (April 1933): 448–474 in JSTOR

- Davis, Harold E. The Americas in History (1953), older textbook

- Egerton, Douglas R. et al. The Atlantic World: A History, 1400–1888 (2007)

- Eltis, David. The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas (2000).

- Hinderaker, Eric; Horn, Rebecca. "Territorial Crossings: Histories and Historiographies of the Early Americas," William and Mary Quarterly, (2010) 67#3 pp. 395–432 in JSTOR

- Lockhart, James, and Stuart B. Schwartz. Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil (1983).

- Merriman, Roger Bigelow. The Rise of The Spanish Empire in the Old World and in the New (4 vol. 1934)

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. The European Discovery of America: The northern voyages, A.D. 500–1600 (1971)

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. The European Discovery of America: The southern voyages, 1492–1616 (1971)

- Parry, J.H. The Age of Reconnaissance: Discovery, Exploration, and Settlement, 1450–1650 (1982)

- Sarson, Steven, and Jack P. Greene, eds. The American Colonies and the British Empire, 1607–1783 (8 vol, 2010); primary sources

- Sobecki, Sebastian. "New World Discovery". Oxford Handbooks Online (2015). doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935338.013.141

- Starkey, Armstrong (1998). European-Native American Warfare, 1675–1815. University of Oklahoma Press ISBN 978-0-8061-3075-0

- Vickers, Daniel, ed. A Companion to Colonial America (2003)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: European colonization of the Americas |

_1.083_JUAN_PONCE_DE_LE%C3%93N.jpg.webp)