Carlos Reygadas

Carlos Reygadas Castillo (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈkaɾlos rejˈɣaðas]; born October 10, 1971) is a Mexican filmmaker. Influenced by existentialist art and philosophy, Reygadas' movies feature spiritual journeys into the inner worlds of his main characters, through which themes of love, suffering, death, and life's meaning are explored.

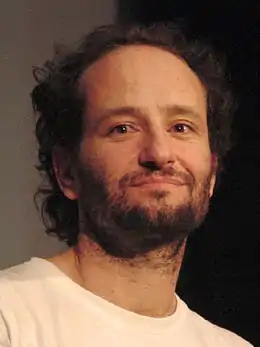

Carlos Reygadas | |

|---|---|

Reygadas at the Tokyo International Filmfest in 2009 | |

| Born | October 10, 1971 |

| Occupation | Film director, producer and screenwriter |

| Years active | 1997 - present |

Reygadas has been described as "the one-man third wave of Mexican cinema";[1] his works are generally considered art films, and are known for their expressionistic cinematography, long takes, and emotionally charged stories. His first and third films, Japón (2002) and Silent Light (2007), made him one of Latin America's most prominent writer-directors, with various critics having named Silent Light as one of the best films of its decade. His films Battle in Heaven (2005) and Post Tenebras Lux (2012) divided critics.

He has co-produced other directors such as Amat Escalante (Sangre, Los Bastardos, Heli), Carlos Serrano Azcona (The Tree) or Pedro Aguilera (The Influence).

.jpg.webp)

Early life

Reygadas first became fascinated with cinema in 1987, upon watching the works of the acclaimed Soviet/Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, who had died the previous year. In 1997, he entered a film competition in Belgium with his first short film, Maxhumain.

Japón

Two years after the release of Maxhumain, Reygadas began writing his first feature-length movie. Shooting for the film, named Japón, began in 2001. When finished, the film was presented at the Rotterdam Film Festival and received a special mention for the Caméra d'Or award at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival, as well as the Coral Award of the Havana Film Festival. Many critics argued that Japón (2002) revolutionized Mexican cinema by defying the conventions of dramatic structure and inventing a new cinematographic language that reflects the sensory world humans inhabit while expressing life as an transcendental experience. The film's title questions a simplistic correlation between signifier and signified, for although it is named after Japan, the island country itself is never portrayed, or even mentioned, in any way throughout; the story is set in a remote and impoverished Hidalgo town.

The harsh atmosphere of this region is clear, but its remoteness also creates a dreamlike nature that accentuates the metaphysical crisis the protagonist is experiencing. The plot follows the ascension of a man up a deep ravine where he plans to commit suicide, but is finally saved when he falls in love with Ascen (short for Ascension), an old religious and indigenous woman with whom he ultimately has sexual relations. The relation between these two characters has an clear allegorical significance that goes beyond its pure physicality and exposes the ultimate aim of an encounter, the true purpose of all human connectability. In this respect, although Japón focuses on the inner problems of a single individual, and the protagonist's relation both with the old woman and with the rustic surrounding where the story takes place, in its core it "reveals the potential that cinema has to be truly cosmopolitan, to the extent that it gives us structures for developing empathy towards the foreign and the unfamiliar, and for understanding more deeply the divide between self and other.".[2]

Japón contains a number of scenes of real animal cruelty and the British Board of Film Classification demanded cuts for its UK release in accordance with the Cinematograph Films (Animals) Act 1937. The excised scenes are described as an unsuccessful attempt to strangle a bird which then stumbles around injured on the ground and a dog being forced to 'sing along' to a song through the application of a painful stimulus.[3] The film also includes an unsimulated scene of a bird being shot down and then killed by having its head torn off, and the (off camera) slaughter of a pig.[4]

Battle in Heaven (2005)

In Reygadas' next film, the director once again presents an ontological exploration into the interior of his characters. This time the film follows Marcos, a working class man, who falls into an existential crisis when a child kidnapped by his wife and him, tragically dies. Marcos' remorse becomes even more excruciating when he kills Ana, the free-spirit daughter of his employer, with whom he has sexual relations. This murder deepens Marcos sense of guilt and leads him in a long and painful pilgrimage of repentance to the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe. During the journey Marcos transforms into a Christ-like figure that eventually assumes a purifying, sacrificial function as he dies inside the famous Mexican church. Battle in Heaven competed for the Palme d’Or at the 2005 Cannes Film Festival and gained worldwide notoriety for its graphic depiction of sexual encounters between its characters .[5]

Silent Light (2007)

Similarly to Japón, in his third movie, Silent Light (2007), Reygadas' shatters the very notion that art in “developing nations" should be read as a social, historical or cultural reference to their country of origin. This film, set in a historic Mennonite community in Chihuahua, Mexico, tells the story of a married man who falls in love with another woman, thus threatening the stability of his family and their place within the conservative community they live in. The dialogue is written in Plautdietsch language, the Low German dialect of the Mennonites, and hence questions a stereotypical conception of what defines Mexico and Mexicans alike. Furthermore, Silent Light shows several similarities to Ordet (1955) by Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer. Although Reygadas' film is not a remake of the European movie it is to a great degree influenced by it, thus accentuating the universality of his work. American director Martin Scorsese described Silent Light as "a surprising picture, and a very moving one as well,",[6] while Manohla Dargis of The New York Times called it "an apparently simple story about forgiving" in which "the images are of extraordinary beauty" and "the characters seem to be illuminated from the inside." . Silent Lightwas very positively reviewed by most critics, and was selected as the Mexican entry for the Best Foreign Language Oscar at the 80th Academy Awards. It was also nominated for Best Foreign Film at the 24th Independent Spirit Awards and gained nine nominations, including all major categories, in the Ariel Awards, the Mexican national film awards. Furthermore, the film competed for the Palme d'Or at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival, and came away as winner of the Jury Prize.[7] The magazine Sight & Sound rated it number 6 on their list of the top films of 2007, while Roger Ebert ranked the film one of the top ten independent films of 2009.[6]

Post Tenebras Lux (2012)

In early 2012, Reygadas released Post Tenebras Lux, a semi-autobiographical fiction film, he said has "feelings, memories, dreams, things I’ve hoped for, fears, facts of my current life." As film critic Francine Prose has written, the movie "shifts back and forth between present and past, reality and fantasy, childhood and adulthood [and] offers us a set of images and sequences to which it repeatedly returns; with each of these reprises the image or sequence takes on additional meaning, depth, and nuance."[8] In an interview at the Berlin Festival, Reygadas said that "reason will intervene as little as possible, like an expressionist painting where you try to express what you're feeling through the painting rather than depict what something looks like." The film was shot in Mexico, Britain, Spain, and Belgium, all places where Reygadas has lived, and at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival won the prize of Best Director Award.[9]

Currently, Reygadas in working on his fifth film, titled Donde nace la vida, (2016) with the collaboration of Uruguayan cinematographer Diego Garcia, who worked in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Love and in Khon Kaen and Yulene Olaizola’s Fogo. The film’s executive producer and Reygadas’s long-time business partner, Jaime Romandia, has stated that the film is “a simple but powerful story of love and loss of love, in open couple relationships, emotional phases on the downfall set in the context of Mexico’s fighting bull-breeding ranches.”[10] In addition to working in his own films, in 2004 Reygadas has also co-produced the film Sangre directed by the young filmmaker Amat Escalante who had worked as his assistant in Battle in Heaven. Presented at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival, Sangre won in the Un Certain Regard section and was also scrrened in other festivals, such as the Toulouse Film Festival, the International Film Festival Rotterdam, the San Sebastian International Film Festival, and the Austin Film Festival. Furthermore, he has worked with the Spanish director and producer Jaime Rosales (Fresdeval Films), in the film El árbol (The Tree). This Spanish-Mexican co-production was directed by Carlos Serrano Azcona and starred Bosco Sodi, a contemporary artist, as the main character. The film was presented at the 2009 Rotterdam Film Festival and received positive reviews.

Directorial style

Reygadas’s use of nonprofessional actors shows influence from Italian neorealist philosophies on cinema. While this is a characteristic found in many independent movies, Reygadas is set apart by his ability to fully engage with his actors while guiding them through an internal process by which they can embody scenes that are both physically and emotionally demanding. Reygadas has metaphorically likened the relation between a director and his or her actors to a complete vote of confidence in which both take a risk and enter an adventure: "Pretend I'm a climber and invite you to the Everest. I tell you that I have gone twice and there are certain risks: you can have a stroke, fall, or die because of an avalanche. You decide whether or not to go up with me. And that's it."[11] For him, cinema is closer to poetry than to the dramatic arts and hence more focused on capturing the essence of a character through the person filmed than the individual's acting ability.

Reygadas’s use of long takes and wide shots have been said to depict the sublime as an aesthetic quality found in nature, that can manifest itself both as a terrifying vital force and in more subtle ways. He has opted to shoot all but two of his films in CinemaScope, and often employs an unconventional editing technique that greatly contributes to a lyrical quality in how his narratives unfold.

Filmography

| Year | Original title | English title | Production country | Language | Length | Award nominations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Maxhumain | MaxHumain | Belgium | Silent | 10 min | |

| 2002 | Japón | Japón | Mexico | Spanish | 130 min | Directors Fortnight – "Special Mention" Camara d'Òr Award |

| 2005 | Batalla en el Cielo | Battle in Heaven | Mexico, France, Germany | Spanish | 105 min | Cannes Film Festival "In Competition" |

| 2007 | Luz Silenciosa (aka Stellet Licht) | Silent Light | Mexico, France, Germany, Netherlands | Plautdietsch | 110 min | Cannes Film Festival "In Competition" Jury Prize Award |

| 2010 | Este es mi Reino | This is my Kingdom | Mexico | Spanish | 10 min | Berlin Film Festival |

| 2012 | Post Tenebras Lux | Post Tenebras Lux | Mexico, France, Germany, Netherlands | Spanish | 110 min | Cannes Film Festival "In Competition" Best Director Award. |

| 2018 | Nuestro Tiempo | Our Time | Mexico | Spanish | 173 min | Venice Film Festival "In Competition" |

References

- "Sight & Sound's films of the decade". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- "Cosmopolitan Aesthetics in the Films of Carlos Reygadas". Flowtv.org. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- Japon - Alejandro Ferretis, Magdalena Flores, Yolanda Villa

- Austin360 Movies: 'Japon' Reviews - Los Angeles Times

- "Festival de Cannes: Battle in Heaven". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- "Silent Light" Archived 2010-11-07 at the Wayback Machine, Film Forum website

- "Festival de Cannes: Silent Light". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-12. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2013/05/01/someone-else-memory-post-tenebras-lux/

- "Awards 2012". Cannes. Retrieved 2012-05-27.

- https://variety.com/2015/film/global/mantarraya-jaime-romandia-carlos-reygadas-amat-escalante-1201616621/

- http://www.animalpolitico.com/2012/11/quien-diablos-es-carlos-reygadas