Catharine Trotter Cockburn

Catharine Trotter Cockburn (16 August 1679 – 11 May 1749) was an English novelist, dramatist, and philosopher. She wrote on moral philosophy, theological tracts, and had a voluminous correspondence.

Catharine Trotter Cockburn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Catharine Trotter 16 August 1679 London, England |

| Died | 11 May 1749 (aged 69) Longhorsley, England |

| Resting place | Longhorsley |

| Occupation | novelist, dramatist, philosopher. |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | English |

| Genre | correspondence |

| Subject | moral philosophy, theological tracts |

| Spouse | Patrick Cockburn (m. 1708) |

Trotter's work addresses a range of issues including necessity, the infinitude of space, and the substance, but she focuses on moral issues. She thought that moral principles are not innate, but discoverable by each individual through the use of the faculty of reason endowed by God. In 1702, she published her first major philosophical work, A Defence of Mr. Lock's [sic.] An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. John Locke was so pleased with this defence that he made gifts of money and books to his young apologist acting through Elizabeth Burnet who had first made Locke aware of Trotter's "Defence".[1]

Her work attracted the attention of William Warburton, who prefaced her last philosophical work. She also had a request from the biographer Thomas Birch to aid him in compiling a collection of her works. She agreed to the project but died before the work could be printed. Birch posthumously published a two-volume collection entitled The Works of Mrs. Catharine Cockburn, Theological, Moral, Dramatic, and Poetical in 1751. It is largely through this text that readers and history have come to know her.

Early years and education

Catharine Trotter was born in London, on 16 August 1674 or 1679.[lower-alpha 1] Both her parents were Scotch. Her father, Captain David Trotter, was a commodore in the Royal Navy, personally known to King Charles II, and the Duke of York, who admired his high qualities and appreciated his distinguished services. Captain Trotter assisted in the demolition of Tangier in 1683, and being subsequently sent to convoy the fleet of merchant ships belonging to the Turkey Company, died of the plague at Alexandretta (Iscanderoon), early in the year 1684. His property having fallen into dishonest hands, the two-fold affliction of bereavement and poverty fell at once upon his widow and children. Her mother was Sarah Bellenden, a near relation of Lord Bellenden, and of the Duke of Lauderdale, and the Earl of Perth.[4]

Trotter was raised Protestant but converted to Roman Catholicism at an early age.

During the short remainder of King Charles II.’s reign, Mrs. Trotter had a pension from the Admiralty, and Queen Anne made her an allowance of 20 £ a-year. It is to be supposed that the widow also received assistance from her husband’s brother, and from her own high-born and wealthy cousins, in bringing up her two fatherless children. Both were daughters. The elder married Dr. Inglis, a medical officer, who attended the Duke of Marlborough in his campaigns, and became physician-general to the army.[4]

Catharine, the youngest, was early remarkable for her sagacious intellect, for her facility in acquiring knowledge, her cleverness in teaching herself the art of penmanship, and her delight in making extemporary verse. Nothing is recorded of her education, but from her own allusion to it in her "Poem on the Busts", it may be inferred to have been slight and ordinary. Nothing, however, could repress her eager desire for information; and obstacles, as usual, proved incentives to effort. She read with avidity, and wrote with emulative zeal; works of imagination occupying, as in such cases they are wont, her childish attention; and these, as her reasoning powers matured, and her judgment became formed, giving place to tractates and treatises on moral philosophy and religion. She taught herself the French language, and, with the assistance of a friend, acquired the Latin. Her Verses written at the age of fourteen, and sent to Mr. Beville Higgons, on his sickness and recovery from the small-pox, though rather a bold avowal of sympathy with the “lovely youth,” and of admiration for his matchless charms,” were evidently well-meant admonitions to resignation, and to the conscientious application of the high qualities and fine “parts” ascribed to him. [5]

Early productions

Her muse was always didactic, and although her Songs, after the fashion of her time, were full of amatory context, they inculcated self-government and morality. The professional connections of her father, the aristocratic relationships of her mother, and the celebrity early won by her own extraordinary talents, gained her a large circle of acquaintance; and although straitened in the means of subsistence, and probably possessing little of her own but the earnings of her pen, Trotter moved in the best society, and was a frequent and welcome guest in the houses of the rich and great. Her beauty, and the unaffected sweetness of her manners, bore the charm of unasserted mental superiority.[5]

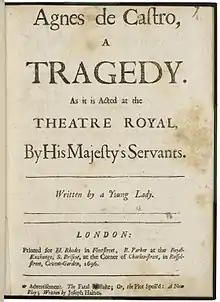

Trotter was a precocious and largely self-educated young woman, who had her first novel (The Adventures of a Young Lady, later retitled Olinda's Adventures) published anonymously in 1693, when she was but 14 years old. Her first published play, Agnes de Castro, was staged two years later, in the year 1695, at the Theatre Royal, and printed in the following year, with a dedication to the Earl of Dorset and Middlesex, from which it appears that his Lordship was one of her personal friends and advisers. This tragedy was not based upon historic fact, but upon Aphra Behn’s English translation of a French novel.[6]

In 1696, she was famously satirised alongside Delarivier Manley and Mary Pix in the anonymous play, The Female Wits. In it, Trotter was lampooned in the figure of "Calista, a lady who pretends to the learned languages and assumes to herself the name of critic." The following year, Trotter addressed to William Congreve a set of complimentary verses on his The Mourning Bride, and thus either created or strengthened the interest which that poet took in her literary proceedings. His published letter to her shows that they had been previously acquainted.[6]

In 1698, her second tragedy and arguably best-liked play, Fatal Friendship, was performed at the then-new theatre in Lincoln's-Inn-Fields. It was afterwards printed with a dedication to the Princess of Wales, and not only established Trotter's reputation as a dramatic writer, and brought a shower of complimentary verses, but increased the number of her powerful, fashionable, and eminent friends. It may reasonably be supposed, produced great pecuniary profit.[6]

Prefixed to her Fatal Friendship are many sets of eulogistic verses addressed to the authoress; one by P. Harman, who also wrote the prologue; one by an anonymous writer, probably Lady Sarah Piers; and yet another, written by the playwright, John Hughes, who hailed her as “the first of stage reformers.” The language is plain and unaffected, but occasionally deformed, after the colloquial fashion introduced at the Restoration, by the abbreviated words “ ’em” for them. The plot is commonplace, but well complicated, and it produces some good dramatic situations. The moral drawn at the conclusion is:— “None know their strength, let the most resolute Learn from this story to distrust themselves, Nor think by fear the victory less sure; Our greatest danger is when we’re most secure." This tragedy, having been deemed by contemporary critics of the time as the best of Trotter's dramatic compositions, left the reader little cause to join in Dr. Birch's regret that want of space enforced the omission of the four other plays from his edition of her works.[7]

In 1700, she was one of the presumptuous Englishwomen who, under the several names of the Nine Muses, bewailed in verse the death of John Dryden. She was consequently praised and addressed as a Muse by a troop of admiring rhymers.[6]

Early in the year 1701, her comedy of Love at a Loss, or Most Votes carry it, was performed at the Theatre Royal, and published in the month of May of the same year, with a dedication to Lady Piers. “She had,” remarks Dr. Birch, “contracted a very early esteem for, and most intimate and unreserved friendship,” with Trotter. Later in the same year, her third tragedy, The Unhappy Penitent, was performed at Drury Lane, and published in August, with a dedication to Lord Halifax, and a set of verses, by Lady Piers, prefixed, inscribed “To the excellent Mrs. Catherine Trotter”. Also in 1701, she wrote her Defence of Mr. Locke’s Essay of Human Understanding, and it was published in May 1702. This gained for her the personal friendship of Locke and of Lady Masham, and was, through them, the means of introducing her to many eminent persons, among them being Mr. Peter King, then a barrister and member of parliament, who was the maternal nephew of Locke.[8]

Religious conversions

Roman Catholic Church

Considering the position and connections of her parents, it is probable that Trotter had not been trained at an early age to piety, and consequently when a crisis of the soul occurred, she probably met with a Roman Catholic teacher, and, as a natural result, she zealously adopted his creed. In this she continued for many years, resting quiescently upon its first impressions. Meanwhile, her strict observance of the fast-days proved so injurious to her health, that in October 1703, her friend and physician, Dr. Denton Nicholas, wrote her a letter of serious remonstrance upon the subject, and desired her “to abate of those rigours of abstinence, as insupportable to a constitution naturally infirm,” requesting that his opinion might be communicated to her friends and to her confessor.[9]

Her health, even at its best, was too delicate to allow her to walk more than a mile to church and back, on a summer's day, without fatigue which amounted to illness; and a weakness of sight always rendered it painful to her to write by candlelight. Yet this fragile woman possessed self-relying energy which enabled her not only to sustain the mental and manual labour of careful literary composition through continuous months and years, but also to transact with methodical exactness all the complicated business attendant upon the performance, printing, and publication of her works.[10]

From 1701, until her marriage in 1708, Catherine Trotter kept up a regular correspondence with her friend George Burnet, Esq., of Kemnay. During the greater part of the period he traveled in foreign lands, and more especially at the courts of Berlin and Hanover, where be spread the fame of “la nouvelle Sappho-Ecossoise,” and excited the curiosity of Leibnitz to become acquainted with her philosophical works. It may be inferred from many passages in his letters that he would gladly have raised for himself an amorous interest with this young friend; and from hers, that, with unaffected candour and cordial esteem, she repelled every approach towards a declaration of love. She had many admirers, but never was led by the persuasions of her friends, or the temptations of wealth and rank, to encourage the addresses of men for whom she felt no preference.[10]

In 1704, Trotter composed a poem on the Duke of Marlborough's gaining the battle of Blenheim, which, being highly approved of by the hero and his family, was put into print. About that period she had some hopes of obtaining, through the powerful interest of the Marlborough family, a pension from the crown, to which her father's long services and losses in the cause of his King and country gave a plausible claim. This, however, she failed to obtain, and received only a gratuity. After the battle of Ramilies, in 1706, she produced another poem in praise of the Duke of Marlborough, and on both occasions her verses were ranked among the best which recorded his fame. In the same year, her tragedy, called The Revolution of Sweden, founded on Vertot's account of Gustavus Ericson, was performed at the Queen's Theatre in the Haymarket; and subsequently printed, with a dedication to Lady Harriet Godolphin, eldest daughter of the great Duke, and after his decease Duchess of Marlborough in her own right.[11]

Her sister, Mrs. Inglis, residing at Salisbury, and her mother spending much of her time there, Catherine was induced to make long visits to that city, extending sometimes to the period of fifteen months. But her favourite abode was at “Mr. Finney’s, in Beaufort Buildings on the Strand,” where, in private lodgings, she could, without domestic restraint or the disturbance of young children, give herself up to literary occupations. Among the happy results of her sojournings at Salisbury was her acquaintance with Bishop Gilbert Burnet, and with his third wife, Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Sir Richard Blake, and widow of Robert Berkeley, Esq, of Spetchley. Mrs. Burnet, who had a large, independent income, took an affectionate interest in Trotter until Mrs. Burnet died in 1709.[11]

Return to the Church of England

In Trotter's mind a sense of duty towards God, and a desire to reform and benefit the world, were ever predominant; but at different periods of her life she sought to effect this object by different means. In the year 1707, after a course of severe study, deep reflection, and earnest prayer, she abjured the Roman Catholic faith, and wrote and published her Two Letters concerning a Guide in Controversies, to which a preface by Bishop Burnet was prefixed. The first letter was addressed to Mr. Bennet, a priest, and the second to Mr. Harman, as a rejoinder to an answer which she had received.[12] She made strong, clear and reasoned arguments for her change of faith.[12] No scruple ever again affected her staunch adherence to the orthodox faith of the Church of England.[13]

Reverend Cockburn

In the summer of 1707, while staying with Madame de Vere, an invalid who resided at Ockham Mills, near Ripley, Surrey, she met with a young clergyman named Fenn, of whose preaching, conversation, and character, she thoroughly approved. Mr. Fenn fell deeply in love with her, made her an offer of marriage, and obtained for his suit the sanction and intercession of Lady Piers. Catherine Trotter accepted his friendship, and, but for the preference she already felt for another person, would have judged it right to marry him. The favoured rival was Rev. Patrick Cockburn, a scholar and a gentleman, distantly related to the Burnet family and to her own, with whom she had for some months held a friendly correspondence, in which they discussed those subjects of philosophical and practical religion which were of principal interest to both. The addresses of Mr. Fenn brought mutual conviction, and matters came to a climax.[13]

Pause in writing

Rev. Cockburn confessed his love, proposed, and was accepted. He took holy orders in the Church of England in 1708, married Trotter, received the “Donative” of Nayland, near Colchester, and, leaving his bride in London to arrange her affairs and to purchase furniture, he took possession of his pastoral charge in June, and welcomed her to their new home in the autumn of the same year.[13]

How long they resided there, neither Dr. Birch nor Trotters's writings suggest; but, in the course of time, Rev. Cockburn accepted the curacy of St. Dunstan's Church, Fleet-street, and returned with his family to London, where they resided until the year 1714, when the death of Queen Anne took place. The oath of abjuration required on the accession of King George I. aroused scruples in the mind of Rev. Cockburn, and he refused to take it, although he conscientiously offered up the public prayers for the reigning sovereign and the royal family. He was consequently deprived of his employment in the church, and reduced to poverty. During the next twelve years, he maintained his family by teaching Latin to the students of the Academy in Chancery Lane, while his wife, ever anxious for self-improvement, took up household duties, industriously applied herself to needlework, and all sorts of manual occupations, and cheerfully devoted her faculties to the solace of her husband, and to the education of her children.[13]

Return to writing

From the year of her marriage, 1708, until 1724, Trotter had published nothing. In the latter year, she wrote her "Letter to Dr. Holdsworth", and having sent it to him, and received an elaborate controversial answer, she published her "Letter" in January 1727. To this, Dr. Winch Holdsworth publicly replied, and Trotter wrote an able rejoinder; but the booksellers not being willing to undertake its responsibility, the "Vindication of Mr. Locke’s Christian Principles from the injurious imputations of Dr. Holdsworth", remained in manuscript until it was published among her collected works.[14]

The best of her productions in verse was "A Poem, occasioned by the Busts set up in the Queen’s Hermitage, designed to be presented with a book in vindication of Mr. Locke, which was to have been inscribed to Her Majesty". With considerable skill and persuasive sweetness she drew an argument from the honour done by Queen Caroline to the busts of Clarke, Locke, and Newton, and the patronage which Her Majesty had extended even to the rural bard, Nicholas Duck. Although much has been said and written about Locke by the ablest metaphysicians of his age, and of each succeeding generation, it may be questioned whether his own meaning in his own words has ever been more truly construed than by Trotter. What she wrote concerning his opinions during his life was approved by Locke himself; what she wrote of them after his decease was acknowledged to be correct by his most intimate associates, to whom he had frequently and familiarly expounded them.[15]

In 1726, Rev. Cockburn convinced himself of the propriety of taking the Oath of Abjuration upon the ascension of George I, to which he had so long objected. He was appointed to St. Paul's Chapel in Aberdeen in the following year.[16] Thither he was accompanied by his family; and his wife bade, in that year, an everlasting farewell to London, the scene of her many triumphs and many trials.[17]

Soon after their removal, her friend, the Lord High Chancellor King, presented her husband to the living of Long Horseley, near Morpeth, in the county of Northumberland; but they continued at Aberdeen until the year 1737, when the Bishop of Durham ordered him to take up his residence in his parish. The clerical residence stood so far from the church of Long Horseley, that when rough weather and feeble health disabled Trotter from riding on horseback to attend the Sunday services, she was constrained to stay at home, unless a still more distant neighbor, Mrs. Ogle, chanced to be in the country, and to give her a seat in her chaise and four, or her coach and six.[17]

In 1732, while living at Aberdeen, she wrote the "Verses occasioned by the Busts in the Queen’s Hermitage", which were printed in the Gentleman’s Magazine for May 1737. In August 1743, her "Remarks upon some Writers in the Controversy concerning the Foundation of Moral Duty and Obligation" were published in a serial called "The History of the Works of the Learned". These ‘"Remarks" were well received, and excited great admiration, and Trotter's friend, Dr. Sharp, archdeacon of Northumberland, having read them in manuscript, engaged her in an epistolary discussion on the subject of which they treat. The correspondence began on 8 August 1743 and was concluded on 2 October 1747.[14]

Dr. Rutherford's "Essay on the Nature and Obligations of Virtue" having appeared in 1744, her active mind was again aroused for public controversy, and in April 1747, her "Remarks upon the Principles and Reasonings of Dr. Rutherford’s Essay on the Nature and Obligations of Virtue, in Vindication of the contrary Principles and Beasonings enforced in the Writings of the late Dr. Samuel Clarke", were published with a preface by Bishop Warburton. The extraordinary reputation acquired by this able work, suggested to some friends, who submitted the scheme to Lady Isabella Finch, the thought of raising a subscription for the republication of all Trotter's works, which the author herself undertook to edit. This plan was zealously supported by Trotter's fashionable and eminent friends, but uncontrollable circumstances prevented its full execution.[18]

Style and themes

In some verses entitled "Calliope’s Directions how to Deserve and Distinguish the Muse’s Inspirations", the strong, clear sense of Trotter is conspicuously shown by her definition of the uses of tragic, comic, and satiric poetry. Of course, as Calliope, she presided only over heroic strains and general eloquence, and it would have been inappropriate to treat of any other kind of verse. The quotation of a few lines demonstrates the style:—[6]

“Let none presume the hallowed way to tread

By other than the noblest motives led :

If for a sordid gain, or glittering fame,

To please without instructing be your aim,

To lower means your grovelling thoughts confine,

Unworthy of an art that’s all divine.”

Trotter's long suspension from writing -sixteen to eighteen years- was noted by the public, as was her resumption of writing. The commentators upon her works over-restrained her own words on the first part of this subject, and drawn from them an unwarranted inference. It should be understood that during those years, Trotter read few new books, yet she had undoubtedly possessed her Bible, the works of Shakespeare and Milton, of Lord Bacon, Cudworth, and Bishop Cumberland. She had lived so long in the propulsive centre of British activity that, when sunk into obscurity, the gathering in of her reflections enriched her more than continued opportunities of observation would have done; and her fine faculties were kept bright and keenly edged by constant use.[19] Extracts of her controversial writings show her style.[20]

In the preface to her "Letter to Dr. Holdsworth", Trotter said the following, with the person here alluded to probably being Lord King:—[21]

"The great zeal Mr. Locke showed for the conversion of deists, the serious veneration he expresses for the Divine Revelation, and (how little soever he was fond of particular systems) the care he took not to oppose any established articles of faith, make it a work worthy a sincere Christian to support his character against the injudiciousness of those who have reproached him as a Socinian heretic, an enemy, an underminer of religion. That there are no plain proofs from his writings to ground such a charge upon, is a sufficient foundation for this defence; but that he was certainly no Socinian, I am farther well assured by the authority of one who was intimate to his most private thoughts, and who is as eminent for his probity, as for the high station he at present possesses.”

In a letter to her niece, dated “Long Horseley, September 29, 1748,” Trotter said:—[22]

"I must own to you I am not myself satisfied, upon a review, of what Mr. Locke has said on moral relations. His plan led him to consider them only with reference to the present constitution of things; and, though he is very free from the charge of making the nature of morality uncertain, I fear he has given occasion to the interested scheme so much in fashion of late, but carried, I dare say, far beyond what he intended.”

It is interesting to know Trotter's opinion of the most illustrious of all her contemporaries, Bishop Butler. In letters to Mrs. Arbuthnot, written at Aberdeen, in 1738, she thus mentions him:—[23]

"He is a most judicious writer, has searched deeply into human nature, and is by some thought obscure; but he thinks with great cleamess, and there needs only a deep attention tounderstand him perfectly. Whilst our modern moralists have contended to establish moral virtue, some on the moral sense alone, some on the essential difference and relations of things, and some on the sole will of God, they have all been deficient; for neither of those principles are suflicient exclusive of others, but all three together make an immoveabl'e foundation for, and obligation to, moral practice; the moral sense, or conscience, and the essential difference of things discovering to us what the will of our Maker is. I have so great an opinion of the author of ‘ The Analogy,’ that I no sooner saw it advertised than I made it my business to inquire after it, and procured the reading it twice. I think the design finely executed, especially in the first part, and all the objections of the deists very well obviated. That valuable performance, and several others that have come out within these few years, are of great use to satisfy and confirm the humble believer in his pious and just opinion, that God best knows by what means it is fit for him, in the wisdom of his government, to be reconciled to mankind.”

In letters of subsequent date, Mrs. Cockburn repeatedly mentioned Bishop Butler with a still deeper sense of the value of his writings. Dating from “Long Horseley, October 2, 1747,” and again addressing Mrs. Arbuthnot, she said the following, which was an all-sufficient exposition of Trotter's theological opinions:—[19]

"I assure you there is not a sentence of that author’s that I would not readily subscribe to, so perfectly I am satisfied with the whole tenor of his doctrine.”

Personal life

Mr. and Mrs. Cockburn had three daughters, Mary, Catherine, and Grissel, and one son, John.[24] A letter of advice to the former, written by his mother for his guidance in early manhood, is full of wisdom and piety. Religion, employment, and women, are the subjects of her discourse. Under the second she says :—“ Divinity is the profession you have been designed for from your birth; but let no views determine your choice to that sacred calling but a sincere desire of promoting the glory of God, and the salvation of men.”[18]

In subsequent letters to her niece, Mrs. Arbuthnot, Trotter often alludes to her “good son” with all the satisfaction of a happy mother. In 1743, a daughter died; and in January 1749, her husband did as well. Under this severe shock, her feeble health gave way. Trotter died at Longhorsley near Morpeth on 11 May 1749.[25] She was buried beside her husband and her youngest daughter, at Longhorsley, and on their tomb was inscribed one sentence, altered from Proverbs xxxi. 31, “Let their own works praise them in the gates.”[18]

Legacy

Despite her one-time renown, Trotter's reputation has steadily waned over the last three centuries and has only been rescued from near obscurity by the efforts of feminist critics, such as Anne Kelley,[26] in the last two decades. Arguably, the predicament of her reputation is attributable to her having written a large amount of work very early in her life and less in her mature years. In other words, her career was extremely front-loaded, and the literati of her period (especially the men) tended to focus on her youth and beauty at the expense of her work. Some literary historians attribute her relative obscurity to a persistent emphasis being placed upon her philosophical work at the expense of her creative writing (especially by her biographer Thomas Birch, who included only one play in his two volume collection of her work and did not mention Olinda's Adventures at all). Though skillful, her philosophical writings were sometimes dismissed as derivative, especially her defence of Locke's Essay—a judgment that could hardly help her reputation.

Much of the scholarly interest in Trotter's dramatic writing now centres on gender studies. Indeed, Trotter herself was cognizant of the limitations her gender placed upon her and often voiced her protest in writing. In the dedication to Fatal Friendship (1698), for example, she remarks that "when a Woman appears in the World under any distinguishing Character, she must expect to be the mark of ill Nature," especially if she enters into "what the other Sex think their peculiar Prerogative." Both Trotter's literary works, in which women dominate the action, and her personal life provide rich subject matter for feminist criticism.

Selected works

- Play productions

- Agnes de Castro, London, Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, December 1695 or 27–31 1696.

- Fatal Friendship, London, Lincoln's Inn Fields, circa late May or early June 1698.

- Love at a Loss, or, Most Votes Carry It (later rewritten as The Honourable Deceiver; or, All Right at the Last), London, Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, 23 November 1700.

- The Unhappy Penitent, London, Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, 4 February 1701.

- The Revolution of Sweden, London, Queen's Theatre, 11 February 1706.

- Books (short titles)

- Agnes de Castro, A Tragedy. (London: Printed for H. Rhodes, R. Parker & S. Briscoe, 1696).

- Fatal Friendship. A Tragedy. (London: Printed for Francis Saunders, 1698).

- Love at a Loss, or, Most Votes Carry It. A Comedy. (London: Printed for William Turner, 1701).

- The Unhappy Penitent, A Tragedy. (London: Printed for William Turner & John Nutt, 1701).

- A Defence of Mr. Lock’s [sic.] Essay of Human Understanding. (London: Printed for Will. Turner & John Nutt, 1702).

- The Revolution of Sweden. A Tragedy. (London: Printed for James Knapton & George Strahan, 1706).

- A Discourse concerning a Guide in Controversies, in Two Letters. (London: Printed for A. & J. Churchill, 1707).

- A Letter to Dr. Holdsworth, Occasioned by His Sermon Preached before the University of Oxford. (London: Printed for Benjamin Motte, 1726).

- Remarks Upon the Principles and Reasonings of Dr. Rutherforth's Essay on the Nature and Obligations of Virtue. (London: Printed for J. & P. Knapton, 1747). Against Thomas Rutherforth.

- The Works of Mrs. Catharine Cockburn, Theological, Moral, Dramatic, and Poetical. 2 vols. (London: Printed for J. & P. Knapton, 1751).

- Other publications

- Olinda’s Adventures; or, The Amours of a Young Lady, in volume 1 of Letters of Love and Gallantry and Several Other Subjects. (London: Printed for Samuel Briscoe, 1693).

- Epilogue, in Queen Catharine or, The Ruines[sic.] of Love, by Mary Pix. (London: Printed for William Turner & Richard Basset, 1698).

- “Calliope: The Heroick [sic.] Muse: On the Death of John Dryden, Esq.; By Mrs. C. T.” in The Nine Muses. Or, Poems Written by Nine severall [sic.] Ladies Upon the Death of the late Famous John Dryden, Esq. (London: Printed for Richard Basset, 1700).

- “Poetical Essays; May 1737: Verses, occasion’d by the Busts in the Queen’s Hermitage.” Gentleman’s Magazine, 7 (1737): 308.

- Works in print

- Catharine Trotter Cockburn: Philosophical Writings. Ed. Patricia Sheridan. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2006. ISBN 1-55111-302-3. $24.95 CDN.

- “Love at a Loss: or, Most Votes Carry It.” Ed. Roxanne M. Kent-Drury. The Broadview Anthology of Restoration & Early Eighteenth-Century Drama. Ed. J. Douglas Canfield. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2003. 857–902. ISBN 1-55111-581-6. $54.95 CDN.

- Olinda’s Adventures, Or, the Amours of a Young Lady. New York: AMS Press Inc., 2004. ISBN 0-404-70138-8. $22.59 CDN.

- Fatal Friendship. A Tragedy in Morgan, Fidelis. The Female Wits: Women Playwrights on the London Stage, 1660–1720. London, Virago, 1981

- "Love at a Loss: or, Most Votes Carry It." in [Kendall] Love and Thunder: Plays by Women in the Age of Queen Anne. Methuen, 1988. ISBN 1170114326

- "Love at a Loss" and "The Revolution of Sweden", in ed. Derek Hughes, Eighteenth Century Women Playwrights, 6 vols, Pickering & Chatto: London, 2001, ISBN 1851966161. Vol.2 Mary Pix and Catharine Trotter, ed. Anne Kelley.

- Catharine Trotter's The Adventures of a Young Lady and Other Works, ed. Anne Kelley. Ashgate Publishing: Aldershot, 2006, ISBN 0 7546 0967 7

Notes

References

- Waithe, edited by Mary Ellen (1991). A history of women philosophers. Dordrecht: Kluwer. pp. 104–105. ISBN 0792309308. Retrieved 5 August 2014.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Recent research, detailed in Anne Kelley, Catharine Trotter: An early modern writer in the vanguard of feminism (Ashgate: Aldershot, 2002) supports this claim, which has been authenticated by the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Kelley, Anne. "Trotter , Catharine (1674?–1749)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 170.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 171.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 172.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 182-83.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 173.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 174.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 175.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 176.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 177.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 178.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 180.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 183-84.

- Yolton, John; Price, John; Stephens, John, eds. (1999). "Cockburn, Catharine (1679?-1749)". The Dictionary of Eighteenth Century British Philosophers. Thoemmes Press. p. 212. ISBN 1855061236.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 179.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 181.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 186.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 184.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 184-855.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 185.

- Virtue and Company 1875, p. 185-86.

- De Tommaso, Emilio Maria. "Catharine Trotter Cockburn (1679?—1749)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. University of Tennessee. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- Kelley, Anne. "Trotter , Catharine (1674?–1749)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- See Catharine Trotter: an early modern writer in the vanguard of feminism, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Virtue and Company (1875). The Art Journal (Public domain ed.). Virtue and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Virtue and Company (1875). The Art Journal (Public domain ed.). Virtue and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Bibliography

- Blaydes, Sophia B. “Catharine Trotter.” Dictionary of Literary Biography: Restoration and Eighteenth-Century Dramatists, Second Series. Ed. Paula R. Backsheider. Detroit: Gale Research, 1989. 317–33.

- Buck, Claire, ed. The Bloomsbury Guide to Women’s Literature. New York: Prentice Hall, 1992.

- Kelley, Anne. Catharine Trotter: An Early Modern Writer in the Vanguard of Feminism. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, 2002.

- Kelley, Anne. “Trotter, Catharine (1674?—1749).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. 4 October 2006.

- Sheridan, Patricia. “Catharine Trotter Cockburn." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University, 2005. 10 October 2006.

- Uzgalis, Bill. "Timeline." University of Oregon. 1995. 12 October 2006.