Catharsis

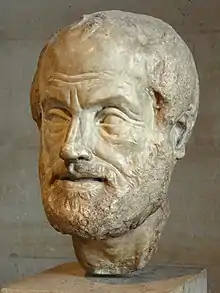

Catharsis (from Greek κάθαρσις, katharsis, meaning "purification" or "cleansing" or "clarification") is the purification and purgation of emotions—particularly pity and fear—through art[1] or any extreme change in emotion that results in renewal and restoration.[2][3] It is a metaphor originally used by Aristotle in the Poetics, comparing the effects of tragedy on the mind of a spectator to the effect of catharsis on the body.[4][5]

Dramatic uses

Catharsis is a term in dramatic art that describes the effect of tragedy (or comedy and quite possibly other artistic forms)[6] principally on the audience (although some have speculated on characters in the drama as well). Nowhere does Aristotle explain the meaning of "catharsis" as he is using that term in the definition of tragedy in the Poetics (1449b21-28). G. F. Else argues that traditional, widely held interpretations of catharsis as "purification" or "purgation" have no basis in the text of the Poetics, but are derived from the use of catharsis in other Aristotelian and non-Aristotelian contexts.[7] For this reason, a number of diverse interpretations of the meaning of this term have arisen. The term is often discussed along with Aristotle's concept of anagnorisis.

D. W. Lucas, in an authoritative edition of the Poetics, comprehensively covers the various nuances inherent in the meaning of the term in an Appendix devoted to "Pity, Fear, and Katharsis".[8] Lucas recognizes the possibility of catharsis bearing some aspect of the meaning of "purification, purgation, and 'intellectual clarification,'" although his approach to these terms differs in some ways from that of other influential scholars. In particular, Lucas's interpretation is based on "the Greek doctrine of Humours," which has not received wide subsequent acceptance. The conception of catharsis in terms of purgation and purification remains in wide use today, as it has for centuries.[9] However, since the twentieth century, the interpretation of catharsis as "intellectual clarification" has gained recognition in describing the effect of catharsis on members of the audience.

Purgation and purification

In his works prior to the Poetics, Aristotle had used the term catharsis purely in its literal medical sense (usually referring to the evacuation of the katamenia—the menstrual fluid or other reproductive material) from the patient.[10] The Poetics, however, employs catharsis as a medical metaphor.

F. L. Lucas opposes, therefore, the use of words like purification and cleansing to translate catharsis; he proposes that it should rather be rendered as purgation. "It is the human soul that is purged of its excessive passions."[11] Gerald F. Else made the following argument against the "purgation" theory:

It presupposes that we come to the tragic drama (unconsciously, if you will) as patients to be cured, relieved, restored to psychic health. But there is not a word to support this in the "Poetics", not a hint that the end of drama is to cure or alleviate pathological states. On the contrary it is evident in every line of the work that Aristotle is presupposing "normal" auditors, normal states of mind and feeling, normal emotional and aesthetic experience.[12]

Lessing (1729–1781) sidesteps the medical attribution. He interprets catharsis as a purification (German: Reinigung),[13] an experience that brings pity and fear into their proper balance: "In real life", he explained, "men are sometimes too much addicted to pity or fear, sometimes too little; tragedy brings them back to a virtuous and happy mean."[14] Tragedy is then a corrective; through watching tragedy, the audience learns how to feel these emotions at proper levels.

Intellectual clarification

In the twentieth century a paradigm shift took place in the interpretation of catharsis: a number of scholars contributed to the argument in support of the intellectual clarification concept.[15] The clarification theory of catharsis would be fully consistent, as other interpretations are not, with Aristotle's argument in chapter 4 of the Poetics (1448b4-17) that the essential pleasure of mimesis is the intellectual pleasure of "learning and inference".

It is generally understood that Aristotle's theory of mimesis and catharsis represent responses to Plato's negative view of artistic mimesis on an audience. Plato argued that the most common forms of artistic mimesis were designed to evoke from an audience powerful emotions such as pity, fear, and ridicule which override the rational control that defines the highest level of our humanity and lead us to wallow unacceptably in the overindulgence of emotion and passion. Aristotle's concept of catharsis, in all of the major senses attributed to it, contradicts Plato's view by providing a mechanism that generates the rational control of irrational emotions. Most scholars consider all of the commonly held interpretations of catharsis, purgation, purification, and clarification to represent a homeopathic process in which pity and fear accomplish the catharsis of emotions like themselves. For an alternate view of catharsis as an allopathic process in which pity and fear produce a catharsis of emotions unlike pity and fear, see E. Belfiore's, Tragic Pleasures: Aristotle on Plot and Emotion.[16]

Literary analysis of catharsis

The following analysis by E. R. Dodds, directed at the character of Oedipus in the Sophoclean tragedy–considered paradigmatic by Aristoteles–Oedipus Rex, incorporates all three of the aforementioned interpretations of catharsis: purgation, purification, intellectual clarification:

...what fascinates us is the spectacle of a man freely choosing, from the highest motives a series of actions which lead to his own ruin. Oedipus might have left the plague to take its course; but pity for the sufferings of his people compelled him to consult Delphi. When Apollo's word came back, he might still have left the murder of Laius uninvestigated; but piety and justice required him to act. He need not have forced the truth from the reluctant Theban herdsman; but because he cannot rest content with a lie, he must tear away the last veil from the illusion in which he has lived so long. Teiresias, Jocasta, the herdsman, each in turn tries to stop him, but in vain; he must read the last riddle, the riddle of his own life. The immediate cause of Oedipus' ruin is not "fate" or "the gods"—no oracle said that he must discover the truth—and still less does it lie in his own weakness; what causes his ruin is his own strength and courage, his loyalty to Thebes, and his loyalty to the truth.[17]

Attempts to subvert catharsis

There have been, for political or aesthetic reasons, deliberate attempts made to subvert the effect of catharsis in theatre. For example, Bertolt Brecht viewed catharsis as a pap (pabulum) for the bourgeois theatre audience, and designed dramas which left significant emotions unresolved, intending to force social action upon the audience. Brecht then identified the concept of catharsis with the notion of identification of the spectator, meaning a complete adhesion of the viewer to the dramatic actions and characters. Brecht reasoned that the absence of a cathartic resolution would require the audience to take political action in the real world, in order to fill the emotional gap they had experienced vicariously. This technique can be seen as early as his agit-prop play The Measures Taken, and is mostly the source of his invention of an epic theatre, based on a distancing effect (Verfremdungseffekt) between the viewer and the representation or portrayal of characters.[18]

"Catharsis" before tragedy

Catharsis before the 6th century BCE rise of tragedy is, for the Western World, essentially a historical footnote to the Aristotelian conception. The practice of purification had not yet appeared in Homer, as later Greek commentators noted:[19] the Aithiopis, an epic set in the Trojan War cycle, narrates the purification of Achilles after his murder of Thersites. Catharsis describes the result of measures taken to cleanse away blood-guilt—"blood is purified through blood",[20] a process in the development of Hellenistic culture in which the oracle of Delphi took a prominent role. The classic example—Orestes—belongs to tragedy, but the procedure given by Aeschylus is ancient: the blood of a sacrificed piglet is allowed to wash over the blood-polluted man, and running water washes away the blood.[21] The identical ritual is represented, Burkert informs us, on a krater found at Canicattini, wherein it is shown being employed to cure the daughters of Proetus from their madness, caused by some ritual transgression.[22] To the question of whether the ritual obtains atonement for the subject, or just healing, Burkert answers: "To raise the question is to see the irrelevance of this distinction".[22]

Catharsis in Platonism

In Platonism, catharsis is part of the soul’s progressive ascent to knowledge. It is a means to go beyond the senses and embrace the pure world of the intelligible.[23] Specifically for the Neoplatonists Plotinus and Porphyry, catharsis is the elimination of passions. This leads to a clear distinction in the virtues. In the second tractate of the first Ennead, Plotinus lays out the difference between the civic virtues and the cathartic virtues and explains that the civic, or political, virtues are inferior. They are a principle of order and beauty and concern material existence. (Enneads, I,2,2) Although they maintain a trace of the Absolute Good, they do not lead to the unification of the soul with the divinity. As Porphyry makes clear, their function is to moderate individual passions and allow for peaceful coexistence with others. (Sentences, XXXIX) The purificatory, or cathartic, virtues are a condition for assimilation to the divinity. They separate the soul from the sensible, from everything that is not its true self, enabling it to contemplate the Mind (Nous).[24]

Therapeutic uses

In psychology, the term was first employed by Sigmund Freud's colleague Josef Breuer (1842–1925), who developed a cathartic method of treatment using hypnosis for persons suffering from intensive hysteria. While under hypnosis, Breuer's patients were able to recall traumatic experiences, and through the process of expressing the original emotions that had been repressed and forgotten, they were relieved of their hysteric symptoms. Catharsis was also central to Freud's concept of psychoanalysis, but he replaced hypnosis with free association.[25]

The term cathexis has also been adopted by modern psychotherapy, particularly Freudian psychoanalysis, to describe the act of expressing, or more accurately, experiencing the deep emotions often associated with events in the individual's past which had originally been repressed or ignored, and had never been adequately addressed or experienced.

There has been much debate about the use of catharsis in the reduction of anger. Some scholars believe that "blowing off steam" may reduce physiological stress in the short term, but this reduction may act as a reward mechanism, reinforcing the behavior and promoting future outbursts.[26][27][28][29][30] However, other studies have suggested that using violent media may decrease hostility under periods of stress.[31] Legal scholars have linked "catharsis" to "closure"[32] (an individual's desire for a firm answer to a question and an aversion toward ambiguity) and "satisfaction" which can be applied to affective strategies as diverse as retribution, on one hand, and forgiveness on the other.[33] There's no "one size fits all" definition of "catharsis", therefore this does not allow a clear definition of its use in therapeutic terms.[34]

Social catharsis

Emotional situations can elicit physiological, behavioral, cognitive, expressive, and subjective changes in individuals. Affected individuals often use social sharing as a cathartic release of emotions. Bernard Rimé studies the patterns of social sharing after emotional experiences. His works suggest that individuals seek social outlets in an attempt to modify the situation and restore personal homeostatic balance.

Rimé found that 80–95% of emotional episodes are shared. The affected individuals talk about the emotional experience recurrently to people around them throughout the following hours, days, or weeks. These results indicate that this response is irrespective of emotional valence, gender, education, and culture. His studies also found that social sharing of emotion increases as the intensity of the emotion increases.[35]

Stages

Émile Durkheim[36] proposed emotional stages of social sharing:

- Directly after emotional effects, the emotions are shared. Through sharing, there is a reciprocal stimulation of emotions and emotional communion.

- This leads to social effects like social integration and strengthening of beliefs.

- Finally, individuals experience a renewed trust in life, strength, and self-confidence.

Motives

Affect scientists have found differences in motives for social sharing of positive and negative emotions.

(1) Positive emotion

A study by Langston[37] found that individuals share positive events to capitalize on the positive emotions they elicit. Reminiscing the positive experience augments positive affects like temporary mood and longer-term well-being. A study by Gable et al.[38] confirmed Langston's "capitalization" theory by demonstrating that relationship quality is enhanced when partners are responsive to positive recollections. The responsiveness increased levels of intimacy and satisfaction within the relationship. In general, the motives behind social sharing of positive events are to recall the positive emotions, inform others, and gain attention from others. All three motives are representatives of capitalization.

(2) Negative emotion

Rimé studies suggest that the motives behind social sharing of negative emotions are to vent, understand, bond, and gain social support. Negatively affected individuals often seek life meaning and emotional support to combat feelings of loneliness after a tragic event.[35]

The grapevine effect

If emotions are shared socially and elicits emotion in the listener then the listener will likely share what they heard with other people. Rimé calls this process "secondary social sharing". If this repeats, it is then called "tertiary social sharing".[35]

Collective catharsis

Collective emotional events share similar responses. When communities are affected by an emotional event, members repetitively share emotional experiences. After the 2001 New York and the 2004 Madrid terrorist attacks, more than 80% of respondents shared their emotional experience with others.[39] According to Rimé, every sharing round elicits emotional reactivation in the sender and the receiver. This then reactivates the need to share in both. Social sharing throughout the community leads to high amounts of emotional recollection and "emotional overheating".

Pennebaker and Harber[40] defined three stages of collective responses to emotional events.

In the first stage, a state of "emergency" takes place in the first month after the emotional event. In this stage, there is an abundance of thoughts, talks, media coverage, and social integration based on the event.

In the second stage, the "plateau" occurs in the second month. Abundant thoughts remain, but the amount of talks, media coverage, and social integration decreases.

In the third stage, the "extinction" occurs after the second month. There is a return to normalcy.

Effect on emotional recovery

This cathartic release of emotions is often believed to be therapeutic for affected individuals. Many therapeutic mechanisms have been seen to aid in emotional recovery. One example is "interpersonal emotion regulation", in which listeners help to modify the affected individual's affective state by using certain strategies.[41] Expressive writing is another common mechanism for catharsis. Joanne Frattaroli[42] published a meta-analysis suggesting that written disclosure of information, thoughts, and feelings enhances mental health.

However, other studies question the benefits of social catharsis. Finkenauer and colleagues[43] found that non-shared memories were no more emotionally triggering than shared ones. Other studies have also failed to prove that social catharsis leads to any degree of emotional recovery. Zech and Rimé[44] asked participants to recall and share a negative experience with an experimenter. When compared with the control group that only discussed unemotional topics, there was no correlation between emotional sharing and emotional recovery.

Some studies even found adverse effects of social catharsis. Contrary to the Frattaroli study, Sbarra and colleagues[45] found expressive writing to greatly impede emotional recovery following a marital separation. Similar findings have been published regarding trauma recovery. A group intervention technique is often used on disaster victims to prevent trauma-related disorders. However, meta-analysis showed negative effects of this cathartic "therapy".[46]

Notes

- "catharsis". Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. Merriam-Webster. 1995. p. 217. ISBN 9780877790426.

- Berndtson, Arthur (1975). Art, Expression, and Beauty. Krieger. p. 235. ISBN 9780882752174.

The theory of catharsis has a disarming affinity with the expressional theory, since it emphasizes emotion, asserts a change in emotion as a result of aesthetic operations, and concludes on a note of freedom in relation to the emotion

- Levin, Richard (2003). Looking for an Argument: Critical Encounters with the New Approaches to the Criticism of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries. p. 42. ISBN 9780838639641.

Catharsis in Shakespearean tragedy involves ... some kind of restoration of order and a renewal or enhancement of our positive feelings for the hero.

- Aristotle, Poetics, 1449b

- "catharsis (criticism)". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Scheff, Thomas J. (1979). Catharsis in Healing, Ritual, and Drama. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-595-15237-7.

- Golden, Leon (1962). "Catharsis". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 93: 51–60. doi:10.2307/283751. JSTOR 283751.

- Lucas, D. W. (1977). Aristotle: Poetics. Oxford University Press. pp. 276–79. ISBN 978-0198140245.

- Nichols, Michael P.; Zax, Melvin (1977). Catharsis in Psychotherapy. John Wiley & Sons Inc, New York. ISBN 978-0470990643.

- Belifiore, Elizabeth S. (1992). Tragic Pleasures: Aristotle on Plot and Emotion. Princeton University Press. p. 300.

- Lucas, F. L. (1927) Tragedy in Relation to Aristotle's Poetics, p. 24

- Else, Gerald F. Aristotle's Poetics: The Argument, p. 440. Cambridge, Massachusetts (1957)

-

Lessing, Gotthold Ephraim (1769). Hamburgische Dramaturgie [Hamburg Dramaturgy]. Deutsches Textarchiv (in German). 2. Hamburg. pp. 183–184. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

Wir dürfen nur annehmen, er habe eben nicht behaupten wollen, daß beide Mittel zugleich, sowohl Furcht als Mitleid, nöthig wären, um die Reinigung der Leidenschaften zu bewirken, die er zu dem letzten Endzwecke der Tragödie macht [...].

- Lucas, F. L. Tragedy in Relation to Aristotle's Poetics, p. 23. Hogarth, 1928

- For example: L. Golden, Aristotle on Tragic and Comic Mimesis, Atlanta, 1992; S. Halliwell, Aristotle's Poetics, London, 1986; D. Keesey, "On Some Recent Interpretations of Catharsis", The Classical World, (1979) 72.4, 193–205.

- Belfiore, Elizabeth S. (1992). Tragic Pleasures: Aristotle on Plot and Emotion. Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press (published 2014). ISBN 9781400862573. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Dodds, E. R. (1966). "On Misunderstanding the 'Oedipus Rex'". Greece and Rome. 13 (1): 37–49. doi:10.1017/s0017383500016144. JSTOR 642354.

- Brecht, Bertold, "La dramaturgie non aristotélicienne", Théâtre épique, théâtre dialectique, éd. Jean-Marie Valentin, Paris, Éditions de L'Arche, 1999, pp. 69–70.

- Burkert, Walter (1992). The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age. Harvard University Press. p. 56. This sub-section depends largely on Burkert.

- Burkert (1992), p. 56.

- Burkert notes parallels with a bilingual Akkadian-Sumerian ritual text: "the knowledgeable specialist, the sacrificial piglet, slaughter, contact with blood, and the subsequent cleansing with water" Burkert (1992, p. 58).

- Burkert (1992), p. 57.

- Reale, Giovanni, (1990) History of Ancient Philosophy, vols. 5, trans. by John R. Catan, Albany: State University of New York Press, vol II, pp. 166–167

- Smith, Andrew, (2004) Philosophy in Late Antiquity, London and New York, Routledge, pp. 62–64

- Strickland, Bonnie, ed. (2001). Catharsis. Gale.

- Bushman, B. J.; Baumeister, R. F.; Stack, A. D. (March 1999). "Catharsis, aggression, and persuasive influence: self-fulfilling or self-defeating prophecies?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 76 (3): 367–376. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.367. PMID 10101875. S2CID 18773447.

- Gannon, Theresa A. (2007). Gannon, Theresa A.; Ward, Tony; Beech, Anthony R.; Fisher, Dawn (eds.). Aggressive offenders' cognition: theory, research, and practice. Wiley series in forensic clinical psychology. 35. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-03401-9.

- Baron, Robert A.; Richardson, Deborah R. (2004). "Catharsis: does 'getting it out of one's system' really help?". Human Aggression. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-48434-6.

- Denzler, Markus; Förster, Jens; Liberman, Nira (January 2009). "How goal-fulfillment decreases aggression" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 45 (1): 90–100. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2008.08.021.

- Bushman, Brad J. (2002). "Does Venting Anger Feed or Extinguish the Flame? Catharsis, Rumination, Distraction, Anger, and Aggressive Responding". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 28 (6): 724–731. doi:10.1177/0146167202289002. S2CID 5686861.

- Ferguson, Christopher; Rueda, Stephanie (2010). "The Hitman study: Violent video game exposure effects on aggressive behavior, hostile feelings and depression" (PDF). European Psychologist. 15 (2): 99–108. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000010.

- Bandes, Susan A. (2009). "Victims, 'Closure,' and the Sociology of Emotion". Law and Contemporary Problems. 72 (2): 1–26. JSTOR 40647733. SSRN 1112140.

- Kanwar, Vik (2002). "Capital Punishment as 'Closure': Limits of a Victim-Centered Jurisprudence". New York University Review of Law and Social Change. 27 (2&3): 215–255. SSRN 978347.

- Powell, Esta. "Catharsis in Psychology and Beyond A Historic Overview".

- Rimé, Bernard (2009). "Emotion Elicits the Social Sharing of Emotion: Theory and Empirical Review". Emotion Review. 1 (1): 60–85. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.557.1662. doi:10.1177/1754073908097189. ISSN 1754-0739. S2CID 145356375.

- Durkheim, Émile (1915). The elementary forms of the religious life, a study in religious sociology. Translated by Swain, Joseph Ward. George Allen & Unwin.

- Langston, Christopher A. (1994). "Capitalizing on and coping with daily-life events: Expressive responses to positive events". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 67 (6): 1112–1125. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1112.

- Gable, Shelly L.; Reis, Harry T.; Impett, Emily A.; Asher, Evan R. (2004). "What Do You Do When Things Go Right? The Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Benefits of Sharing Positive Events". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 87 (2): 228–245. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228. PMID 15301629. S2CID 4609003.

- Rimé, Bernard; Páez, Darío; Basabe, Nekane; Martínez, Francisco (2009). "Social sharing of emotion, post-traumatic growth, and emotional climate: Follow-up of Spanish citizen's response to the collective trauma of March 11th terrorist attacks in Madrid". European Journal of Social Psychology. 40 (6): 1029–1045. doi:10.1002/ejsp.700. ISSN 1099-0992.

- Pennebaker, James W.; Harber, Kent D. (1993). "A Social Stage Model of Collective Coping: The Loma Prieta Earthquake and The Persian Gulf War". Journal of Social Issues. 49 (4): 125–145. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb01184.x. ISSN 1540-4560.

- Reeck, Crystal; Ames, Daniel R.; Ochsner, Kevin N. (2016). "The Social Regulation of Emotion: An Integrative, Cross-Disciplinary Model". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 20 (1): 47–63. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2015.09.003. ISSN 1879-307X. PMC 5937233. PMID 26564248.

- Frattaroli, Joanne (2006). "Experimental disclosure and its moderators: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 132 (6): 823–865. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823. PMID 17073523.

- Finkenauer, Catrin; Luminet, Olivier; Gisle, Lydia; El-Ahmadi, Abdessadek; Linden, Martial Van Der; Philippot, Pierre (1998). "Flashbulb memories and the underlying mechanisms of their formation: Toward an emotional-integrative model". Memory & Cognition. 26 (3): 516–531. doi:10.3758/BF03201160. ISSN 0090-502X. PMID 9610122.

- Zech, Emmanuelle; Rimé, Bernard (2005). "Is talking about an emotional experience helpful? effects on emotional recovery and perceived benefits". Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 12 (4): 270–287. doi:10.1002/cpp.460. ISSN 1099-0879.

- Sbarra, David A.; Boals, Adriel; Mason, Ashley E.; Larson, Grace M.; Mehl, Matthias R. (2013). "Expressive Writing Can Impede Emotional Recovery Following Marital Separation". Clinical Psychological Science. 1 (2): 120–134. doi:10.1177/2167702612469801. ISSN 2167-7026. PMC 4297672. PMID 25606351.

- van Emmerik, Arnold A. P.; Kamphuis, Jan H.; Hulsbosch, Alexander M.; Emmelkamp, Paul M. G. (2002). "Single session debriefing after psychological trauma: a meta-analysis". Lancet. 360 (9335): 766–771. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09897-5. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 12241834. S2CID 8177617.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 660–661.

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: "Catharsis"

- Catholic Encyclopedia: "Mysticism" and "NeoPlatonism"

- Blackwell Reference

- Kohn, Alfie (1992). No Contest: The Cast Against Competition. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-63125-6.

- "Catharsis in Psychology and Beyond: A Historic Overview" by Esta Powell

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Catharsis |

The dictionary definition of catharsis at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of catharsis at Wiktionary