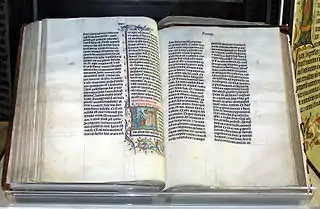

Catholic theology of Scripture

The theology of Scripture in the Roman Catholic church has evolved much since the Second Vatican Council of Catholic Bishops ("Vatican II", 1962-1965). This article explains the theology (or understanding) of Scripture that has come to dominate in the Catholic Church today. It focuses on the Church’s response to various areas of study into the original meaning of texts.[1]

Watershed Council

Vatican II's Dei Verbum (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation), promulgated in 1965, opened the door to acceptance within the Church for much of the scholarly study of the Hebrew and Christian scriptures that had taken place since the 19th century. Developments within the Catholic Church can be traced through documents of the Pontifical Biblical Commission, which oversees scriptural interpretation as it pertains to Catholic teaching.[2] Until Vatican II the decrees of this commission reflected the Counter-Reformation effort to preserve the tradition unchanged, lest errors arising during the Protestant Reformation enter into Catholic belief. Consequent on Vatican II, the Counter-Reformation mentality in the Catholic Church diminished and the ecumenical spirit of openness to what is good in modern studies was embraced. The Council Fathers reiterated what was dogmatic in the previous teaching of the Church, "that the books of Scripture must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error that truth which God wanted put into sacred writings for the sake of salvation."[3] This is the substance of what church dogma (infallible teaching) says. The Council document went on to show an openness to development of doctrine (teaching), since historically growth in understanding has led to more developed theologies[4] – in this case of scriptural interpretation within the Church. The Council Fathers continued:

However, since God speaks in Sacred Scripture through men in human fashion,[5] the interpreter of Sacred Scripture, in order to see clearly what God wanted to communicate to us, should carefully investigate what meaning the sacred writers really intended, and what God wanted to manifest by means of their words. To search out the intention of the sacred writers, attention should be given, among other things, to "literary forms" ... in accordance with the situation of his own time and culture.[6] For the correct understanding of what the sacred author wanted to assert, due attention must be paid to the customary and characteristic styles of feeling, speaking and narrating which prevailed at the time of the sacred writer, and to the patterns men normally employed at that period in their everyday dealings with one another.[7] But, since Holy Scripture must be read and interpreted in the sacred spirit in which it was written,[8] no less serious attention must be given to the content and unity of the whole of Scripture if the meaning of the sacred texts is to be correctly worked out. The living tradition of the whole Church must be taken into account along with the harmony which exists between elements of the faith. It is the task of exegetes to work according to these rules toward a better understanding and explanation of the meaning of Sacred Scripture, so that through preparatory study the judgment of the Church may mature.[9]

In these words and in the ensuing decrees of the Biblical commission, the contextual interpretation of scripture was endorsed, as distinguished from the fundamentalist approach which would hold to the verbal accuracy of every verse of scripture. Catholics, however, remain free to interpret Scripture in any way that does not contradict Catholic dogma.

Areas of scriptural research

At least since Vatican II, Catholic theology has been understood as the search for fruitful understanding of the Church's dogma, doctrine, and practice. While dogma, the most basic beliefs, does not change, Church doctrine includes the many other beliefs that may reflect a single interpretation of dogma, of Scripture, or of the Church's tradition and practice. An example would be the dogma that "Jesus died for our sins." The many ways in which his death on the cross impacts us – or in which it may be called a "sacrifice" – have filled reams in the history of theology. An up-to-date theology of the question can be found in various places, in substantial agreement.[10] How this process works, through the "study of believers", was given at Vatican II:

The Tradition which comes from the Apostles thrives under the assistance of the Holy Ghost in the Church: the understanding of the things and words handed down grows, through the contemplation and study of believers, who compare these things in their heart (cf. Lk 2, 19, 51), and through their interior understanding of the spiritual realities which they experience. The Church, we may say, as the ages pass, tends continually towards the fullness of divine truth, till the words of God are consummated in her.[11]

While biblical criticism began in the 17th century among those who saw the Scriptures as of human rather than divine origin, it has divided into areas of research all of which have proved fruitful for Catholic scripture scholars. These include "criticisms" and approaches described as: textual, source, form, redaction, rhetorical, narrative, semiotic, canonical, socio-scientific, psychological, feminist, liberationist, and Jewish, along with the underlying principles of Catholic hermeneutics. Catholic scholars have also entered seriously into the quest for the historical Jesus, but with a respect for oral and written traditions that distinguishes them from some who have pursued this topic.[12]

Authoritative critique

In 1993 the Catholic Church’s Pontifical Biblical Commission produced "The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church" with the endorsement of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.[13] While expressing an openness to all forms of Biblical criticism, the Commission expressed caveats for Catholics in the use of these methods, so that Scriptural interpretation might be "as faithful as possible to its character both human and divine." More specific observations of the Commission included the following points.

Study of the text across time (historical-critical or diachronic method), including source and form criticism, while "indispensable" for proper understanding of texts, is limited in that it views texts at only one point in their transmission and can divert attention from the richness that the final form of the text has for the Church. But when supplemented by redaction criticism, the earlier stages are valuable in showing the dynamism that produced texts and the complexity of the process. For one example, by giving the Sitz im Leben of the covenant code in Exodus 21-23, form criticism renders intelligible its differences from other law codes preserved in Deuteronomy.

Narrative analysis is to be commended for its appeal addressed to the reader, for bringing out the story and witness character of Scripture for pastoral and practical use. It must remain open to doctrinal elaboration on its content, but by including the informative and performative aspects – the story, of salvation – it avoids "the reduction of the inspired text to a series of theological theses, often formulated in non-scriptural categories and language."

Semiotics, a general philosophical theory of signs and symbols, must be wary of structuralist philosophy with its "refusal to accept individual personal identity within the text and extratextual reference beyond it." The historical context and human authors are important. Formal study of the content of texts cannot excuse us from arriving at its message.

The canonical approach which emphasizes the final form of texts and their unity as the norm of faith, needs to respect the various stages of salvation history and the meaning proper to the Hebrew scripture, to grasp the New Testament's roots in history.

Jewish traditions of interpretation are essential to the understanding of Christian scriptures. But differences must be respected: while the Jewish community and way of life depend on written revelation and oral tradition, Christianity is based on faith in Jesus Christ and in his resurrection.

History of the influence of the text studies how people, inspired by Scripture, are able to create further works, as is seen in creative use of the Song of Songs. Care must be taken that a time-bound interpretation not become the norm for all time.

Socio-scientific criticism includes sociology, which focuses mainly on the economic and institutional aspects of ancient society, and cultural anthropology which focuses on the customs and practices of a particular people. Both study the world behind the text rather than the world in the text. Our knowledge of ancient society is far from complete and it leans toward the economic and institutional rather than the personal and religious. While these disciplines are "indispensable for historical criticism", of themselves they cannot determine the content of revelation.

The psychological approach clarifies the role of the unconscious as a level of human reality and the use of the symbolic as a window to the numinous. But this should be done without detriment to other realities, of sin and of salvation, and of a distinction between spontaneous religiosity and revealed religion – the historical character of the Biblical revelation, its uniqueness.

The liberationist approach draws on an important strand in Biblical revelation, God's accompanying the poor, but other central themes must be allowed to interact with this. Also, if too one-sided it can lead to materialist doctrines and an earthly eschatology.

Feminist approaches are diverse but most fruitful in pointing out aspects of revelation which men have not been quick to observe, e.g., the motherly-fatherly nature of God and the ways in which early Christian communities distinguished themselves from Jewish and Greco-Roman society.

Hermeneutics would bridge the gap between the lived experience of the early church and our own lived experience. Beyond the scientific interpretation of texts it seeks to ascertain the lived faith of the community and its mature life in the Spirit, to reproduce again today a connaturality with the truths of revelation.

Fundamentalist interpretation disregards the human authors who were belabored to express the divine revelation. It often places its faith in one, imperfect translation. And it wills away any development between the words of Jesus and the preaching of the early church which existed before the written texts. Also, by reading certain texts uncritically, prejudiced attitudes, such as racism, are reinforced.

Publications

While Catholic periodical articles written since Vatican II often have direct reference to Scripture, two Catholic periodicals that are dedicated entirely to Scripture are The Bible Today, at the more popular level, and the Catholic Biblical Quarterly, published by the Catholic Biblical Association and including articles with minute Biblical research.

See also

- Brown, Raymond E., Joseph A. Fitzmyer, and Roland E. Murphy, eds. (1990). The New Jerome Biblical Commentary. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-614934-0. See especially: “New Testament Topical Articles” (pp. 587-1475) including “Modern Criticism” and “Hermeneutics” (pp. 1113-1165).

References

- That is, the contextual or "literal" meaning intended by the human author who wrote the text, including the author's unconscious and also divine inspiration. This is in contrast to the fundamentalist manner of reading Scripture “literally”. Both are clarified in this article.

- Pontifical Biblical Commission documents

- cf. St. Augustine, "Gen. ad Litt." 2, 9, 20:PL 34, 270-271; Epistle 82, 3: PL 33, 277: CSEL 34, 2, p. 354. St. Thomas, "On Truth," Q. 12, A. 2, C. Council of Trent, session IV, Scriptural Canons: Denzinger 783 (1501). Leo XIII, encyclical Providentissimus Deus: EB 121, 124, 126-127. Pius XII, encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu: EB 539.

- Vatican II, Constitution on Revelation, article 8,

- St. Augustine, City of God, XVII, 6, 2: PL 41, 537: CSEL. XL, 2, 228

- . St. Augustine, On Christian Doctrine III, 18, 26; PL 34, 75-76.

- Pius XII, loc. cit. Denziger 2294 (3829-3830); EB 557-562.

- cf. Benedict XV, encyclical Spiritus Paraclitus Sept. 15, 1920:EB 469. St. Jerome, "In Galatians" 5, 19-20: PL 26, 417 A.

- Dei Verbum (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation), promulgated by Pope Paul VI on November 18, 1965; No. 12.

- Daly, Robert J. "Sacrifice: the Way to Enter the Paschal Mystery", America, May 12, 2003 – from his "Sacrifice Unveiled or Sacrifice Revisited", Theological Studies, March 2003; Kasper, Walter. 1982 The God of Jesus Christ. (New York: Crossroads, 1982) pp. 191,195; Fitzmyer, Joseph. "Pauline Theology, Expiation". The New Jerome Biblical Commentary. (Prentice Hall: New Jersey, 1990) p. 1399; Zupez, John. "Salvation in the Epistle to the Hebrews", The Bible Today Reader. (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1973).

- Constitution on Revelation, art. 8.

- Meier, John P., A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Doubleday, v. 1, The Roots of the Problem and the Person, 1991, ISBN 0-385-26425-9 v. 2, Mentor, Message, and Miracles, 1994, ISBN 0-385-46992-6 v. 3, Companions and Competitors, 2001, ISBN 0-385-46993-4 v. 4, Law and Love, 2009, ISBN 978-0-300-14096-5

- PBC 1993