List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

These are biblical figures unambiguously identified in contemporary sources according to scholarly consensus. Biblical figures that are identified in artifacts of questionable authenticity, for example the Jehoash Inscription and the bullae of Baruch ben Neriah, or who are mentioned in ancient but non-contemporary documents, such as David and Balaam,[n 1] are excluded from this list.

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

Hebrew Bible (Protocanonical Old Testament)

The Hebrew Bible, known in Judaism by the acronym Tanakh, is the collection of ancient writings that are considered sacred by both Jews and Christians. They tell the story of the Jewish people and their ancestors, starting from the creation narrative and concluding near the end of the 5th century BCE.

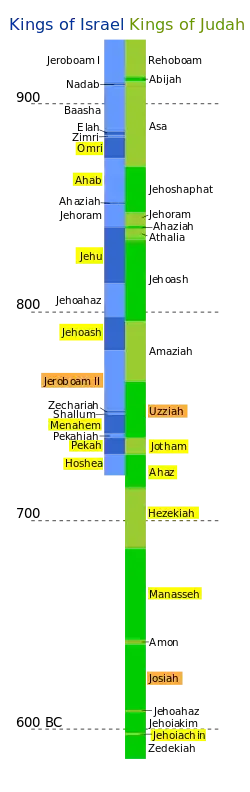

Although the first mention of the name 'Israel' in archaeology dates to the 13th century BCE,[1] contemporary information on the Israelite nation prior to the 9th century BCE is extremely sparse.[2] In the following centuries a small number of local Hebrew documents, mostly seals and bullae, mention biblical characters, but more extensive information is available in the royal inscriptions from neighbouring kingdoms, particularly Babylon, Assyria and Egypt.[2]

| Name | Title | Date (BCE)[n 2] | Attestation and Notes | Biblical references[n 3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adrammelech | Prince of Assyria | fl. 681 | Identified as the murderer of his father Sennacherib in the Bible and in an Assyrian letter to Esarhaddon (ABL 1091), where he is called "Arda-Mulissi".[3][4] | Is. 37:38, 2 Kgs. 19:37† |

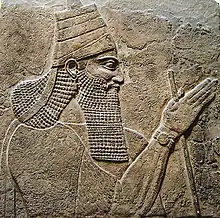

| Ahab | King of Israel | c. 874 – c. 853 | Identified in the contemporary Kurkh Monolith inscription of Shalmaneser III[5] which describes the Battle of Qarqar and mentions "2,000 chariots, 10,000 soldiers of Ahab the Israelite" defeated by Shalmaneser.[6] | 1 Kgs. 17, 2 Chr. 18 |

| Ahaz | King of Judah | c. 732 – c. 716 | Mentioned in a contemporary Summary Inscription of Tiglath-Pileser III which records that he received tribute from "Jehoahaz of Judah".[7] Also identified in royal bullae belonging to Ahaz himself[8] and his son Hezekiah.[9] | 2 Kgs. 16, Hos. 1:1, Mi. 1:1, Is. 1:1 |

| Apries | Pharaoh of Egypt | 589–570 | Also known as Hophra; named in numerous contemporary inscriptions including those of the capitals of the columns of his palace.[10][11] Herodotus speaks of him in Histories II, 161–171.[12] | Jer. 44:30† |

| Artaxerxes I | King of Persia | 465–424 | Widely identified with "Artaxerxes" in the book of Nehemiah.[13][14] He is also found in the writings of contemporary historian Thucydides.[15] Scholars are divided over whether the king in Ezra's time was the same, or Artaxerxes II. | Neh. 2:1, Neh. 5:14 |

| Ashurbanipal | King of Assyria | 668 – c. 627 | Generally identified with "the great and noble Osnappar", mentioned in the Book of Ezra.[16][17] His name survives in his own writings, which describe his military campaigns against Elam, Susa and other nations.[18][19] | Ezr. 4:10† |

| Belshazzar | Coregent of Babylon | c. 553–539 | Mentioned by his father Nabonidus in the Nabonidus Cylinder.[20] According to another Babylonian tablet, Nabonidus "entrusted the kingship to him" when he embarked on a lengthy military campaign.[21] | Dn. 5, Dn. 7:1, Dn. 8:1 |

| Ben-hadad | King of Aram Damascus | early 8th century | Mentioned in the Zakkur Stele.[22] A son of Hazael, he is variously called Ben-Hadad/Bar-Hadad II/III. | 2 Kgs. 13:3, 2 Kgs. 13:24 |

| Cyrus II | King of Persia | 559–530 | Appears in many ancient inscriptions, most notably the Cyrus Cylinder.[23] He is also mentioned in Herodotus' Histories. | Is. 45:1, Dn. 1:21 |

| Darius I | King of Persia | 522–486 | Mentioned in the books of Haggai, Zechariah and Ezra.[24][25] He is the author of the Behistun Inscription. He is also mentioned in Herodotus' Histories. | Hg. 1:1, Ezr. 5:6 |

| Esarhaddon | King of Assyria | 681–669 | His name survives in his own writings, as well as in those of his son Ashurbanipal.[26][27] | Is. 37:38, Ezr. 4:2 |

| Evil Merodach | King of Babylon | c. 562–560 | His name (Akkadian Amēl-Marduk) and title were found on a vase from his palace,[28] and on several cuneiform tablets.[29] | 2 Kgs. 25:27, Jer. 52:31† |

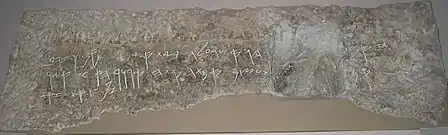

| Hazael | King of Aram Damascus | c. 842 – c. 800 | Shalmaneser III of Assyria records that he defeated Hazael in battle and captured many chariots and horses from him.[30] Most scholars think that Hazael was the author of the Tel Dan Stele.[31] | 1 Kgs. 19:15, 2 Kgs. 8:8, Am. 1:4 |

| Hezekiah | King of Judah | c. 715 – c. 686 | An account is preserved by Sennacherib of how he besieged "Hezekiah, the Jew", who "did not submit to my yoke", in his capital city of Jerusalem.[32] A bulla was also found bearing Hezekia's name and title, reading "Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz king of Judah".[9][33] | 2 Kgs. 16:20, Prv. 25:1, Hos. 1:1, Mi. 1:1, Is. 1:1 |

| Hoshea | King of Israel | c. 732 – c. 723 | He was put into power by Tilgath-Pileser III, king of Assyria, as recorded in his Annals, found in Calah.[34] | 2 Kgs. 15:30, 2 Kgs. 18:1 |

| Jehoash | King of Israel | c. 798 – c. 782 | Mentioned in records of Adad-nirari III of Assyria as "Jehoash of Samaria".[35][36] | 2 Kgs. 13:10, 2 Chr. 25:17 |

| Jehoiachin | King of Judah | 598–597 | He was taken captive to Babylon after Nebuchadrezzar first captured Jerusalem. Texts from Nebuchadrezzar's Southern Palace record the rations given to "Jehoiachin king of the Judeans" (Akkadian: Ya'ukin sar Yaudaya).[37] | 2 Kgs. 25:14, Jer. 52:31 |

| Jehu | King of Israel | c. 841 – c. 814 | Mentioned on the Black Obelisk.[30] | 1 Kgs. 19:16, Hos. 1:4 |

| Johanan | High Priest of Israel | c. 410 – c. 371 | Mentioned in a letter from the Elephantine Papyri.[38] | Neh. 12:22–23 |

| Jotham | King of Judah | c. 740 – c. 732 | Identified as the father of King Ahaz on a contemporary clay bulla, reading "of Ahaz [son of] Jotham king of Judah".[8] | 2 Kgs. 15:5, Hos. 1:1, Mi. 1:1, Is. 1:1 |

| Manasseh | King of Judah | c. 687 – c. 643 | Mentioned in the writings of Esarhaddon, who lists him as one of the kings who had brought him gifts and aided his conquest of Egypt.[27][39] | 2 Kgs. 20:21, Jer. 15:4 |

| Menahem | King of Israel | c. 752 – c. 742 | The annals of Tiglath-Pileser (ANET3 283)[40] record that Menahem paid tribute him, as stated in the Books of Kings.[41] | 2 Kgs. 15:14–23 |

| Mesha | King of Moab | fl. c. 840 | Author of the Mesha Stele.[42] | 2 Kgs. 3:4† |

| Merodach-Baladan | King of Babylon | 722–710 | Named in the Great Inscription of Sargon II in his palace at Khorsabat.[43] Also called "Berodach-Baladan" (Akkadian: Marduk-apla-iddina). | Is. 39:1, 2 Kgs. 20:12† |

| Nebuchadnezzar II | King of Babylon | c. 605–562 | Mentioned in numerous contemporary sources, including the inscription of the Ishtar Gate, which he built.[44] Also called Nebuchadrezzar (Akkadian: Nabû-kudurri-uṣur). | Ez. 26:7, Dn. 1:1, 2 Kgs. 24:1 |

| Nebuzaradan | Babylonian official | fl. c. 587 | Mentioned in a prism in Istanbul (No. 7834), found in Babylon where he is listed as the "chief cook".[45][46] | Jer. 52:12, 2 Kgs. 25:8 |

| Nebo-Sarsekim | Chief Eunuch of Babylon | fl. c. 587 | Listed as Nabu-sharrussu-ukin in a Babylonian tablet.[47][48] | Jer. 39:3† |

| Necho II | Pharaoh of Egypt | c. 610 – c. 595 | Mentioned in the writings of Ashurbanipal[49] | 2 Kgs. 23:29, Jer. 46:2 |

| Omri | King of Israel | c. 880 – c. 874 | Mentioned, together with his unnamed son or successor, on the Mesha Stele.[42] | 1 Kgs. 16:16, Mi. 6:16 |

| Pekah | King of Israel | c. 740 – c. 732 | Mentioned in the annals of Tiglath-Pileser III.[34] | 2 Kgs. 15:25, Is. 7:1 |

| Rezin | King of Aram Damascus | died c. 732 | A tributary of Tiglath-Pileser III of Assyria and the last king of Aram Damascus.[50] According to the Bible, he was eventually put to death by Tiglath-Pileser. | 2 Kgs. 16:7–9, Is. 7:1 |

| Sanballat | Governor of Samaria | fl. 445 | A leading figure of the opposition which Nehemiah encountered during the rebuilding of the walls around the temple in Jerusalem. Sanballat is mentioned in the Elephantine Papyri.[38][51] | Neh. 2:10, Neh. 13:28 |

| Sargon II | King of Assyria | 722–705 | He besieged and conquered the city of Samaria and took many thousands captive, as recorded in the Bible and in an inscription in his royal palace.[52] His name, however, does not appear in the biblical account of this siege, but only in reference to his siege of Ashdod. | Is. 20:1† |

| Sennacherib | King of Assyria | 705–681 | The author of a number of inscriptions discovered near Nineveh.[53] | 2 Kgs. 18:13, Is. 36:1 |

| Shalmaneser V | King of Assyria | 727–722 | Mentioned on several royal palace weights found at Nimrud.[54] Another inscription was found that is thought to be his, but the name of the author is only partly preserved.[55] | 2 Kgs. 17:3, 2 Kgs. 18:9† |

| Taharqa | Pharaoh of Egypt, King of Kush | 690–664 | Called "Tirhaka, the king of Kush" in the books of Kings and Isaiah.[56] Several contemporary sources mention him and fragments of three statues bearing his name were excavated at Nineveh.[57] | Is. 37:9, 2 Kgs. 19:9† |

| Tattenai | Governor of Eber-Nari | fl. 520 | Known from contemporary Babylonian documents.[58][59] He governed the Persian province west of the Euphrates river during the reign of Darius I. | Ezr. 5:3, Ezr. 6:13 |

| Tiglath-Pileser III | King of Assyria | 745–727 | Numerous writings are ascribed to him and he is mentioned, among others, in an inscription by Barrakab, king of Sam'al.[60] He exiled inhabitants of the cities he captured in Israel. | 2 Kgs. 15:29, 1 Chr. 5:6 |

| Xerxes I | King of Persia | 486–465 | Called Ahasuerus in the books of Ezra and Esther.[17][61] Xerxes is known in archaeology through a number of tablets and monuments,[62] notably the "Gate of All Nations" in Persepolis. He is also mentioned in Herodotus' Histories. | Est. 1:1, Dn. 9:1, Ezr. 4:6 |

Deuterocanonicals or biblical apocrypha

The deuterocanon consists of books and parts of books that are included in the Old Testament canon of the Eastern Orthodox and/or Roman Catholic churches, but are not part of the Jewish Tanakh, and are regarded as apocryphal by Protestants. In contrast to the Tanakh, which is preserved in Hebrew (with some Aramaic parts), the deuterocanonical books are preserved mainly in Koine Greek, though Hebrew and Aramaic fragments have been found among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

While the deuterocanon describes events between the eighth and second centuries BCE, most historically identifiable people mentioned in the deuterocanon lived around the time of the Maccabean Revolt (167–160 BCE), by which time Judea had become part of the Seleucid Empire. Coins featuring the names of rulers had become widespread and many of them were inscribed with the year number in the Seleucid era, allowing them to be dated precisely. First-hand information comes also from the Greek historian Polybius (c. 200 – c. 118 BCE), whose Histories covers much of the same period as the Books of Maccabees, and from Greek and Babylonian inscriptions.

| Name[n 4] | Title | Date (BCE)[n 2] | Attestation and Notes | Scriptural references[n 3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander Balas | King of Asia[n 5] | 150–146 | Pretended to be a son of Antiochus Epiphanes, as he is also described in 1 Maccabees.[63] Mentioned in Polybius' Histories.[64] | 1 Macc. 10:1, 1 Macc. 11:1 |

| Alexander the Great | King of Macedon | 336–323 | Referred to by Athenian orator Aeschines,[65][66] and identified on his coins.[67] | 1 Macc. 1:1, 1 Macc. 6:2 1 Macc. 1:10† |

| Antiochus III the Great | King of Asia | 222–187 | Mentioned by contemporary historian Polybius.[68][69] and coins with his name have survived.[70] | 1 Macc. 1:10, 1 Macc. 8:6 |

| Antiochus IV Epiphanes | King of Asia | 175–164 | Known from Polybius' Histories[71][72] and from contemporary coins.[73] | 1 Macc. 10:1, 2 Macc. 4:7 |

| Antiochus V Eupator | King of Asia | 163–161 | Executed by his half-brother Demetrius I when he was 11 years old. Identified in an inscription from Dymi,[74] and on contemporary coins.[75] | 2 Macc. 2:20, 2 Macc. 13:1 |

| Antiochus VI Dionysus | King of Asia | 145–142 | Reigned only nominally, as he was very young when his father died,[76] but he is identified on contemporary coins.[77] | 1 Macc. 11:39, 1 Macc. 12:39 |

| Antiochus VII Sidetes | King of Asia | 138–129 | Dethroned the usurper Tryphon. Coinage from the period bears his name.[78] | 1 Macc. 15† |

| Ariarathes V | King of Cappadocia | 163–130 | Mentioned by Polybius.[79][80] | 1 Macc. 15:22† |

| Arsinoe III | Queen of Egypt | 220–204 | Married to her brother, Ptolemy IV. Several contemporary inscriptions dedicated to them have been found.[81] | 3 Macc. 1:1, 3 Macc. 1:4† |

| Astyages | King of Medes | 585–550 | The contemporary Chronicle of Nabonidus refers to the mutiny on the battlefield as the cause for Astyages' overthrow [82] | Bel and the Dragon 1:1† |

| Attalus II Philadelphus | King of Pergamon | 160–138 | Known from the writings of Polybius.[83][84] | 1 Macc. 15:22† |

| Cleopatra Thea | Queen of Asia | 126–121 | First married to Alexander Balas,[85] later to Demetrius II and Antiochus VII, she became sole ruler after Demetrius' death.[86] Her name and portrait appear on period coinage.[86] | 1 Macc. 10:57–58† |

| Darius III | King of Persia | 336–330 | Last king of the Achaemenid Empire, defeated by Alexander the Great. Mentioned in the Samaria Papyri.[87] | 1 Macc. 1:1† |

| Demetrius I Soter | King of Asia | 161–150 | A cuneiform tablet dated to 161 BCE refers to him,[88] and Polybius, who personally interacted with Demetrius, mentions him in his Histories.[89][90] | 1 Macc. 7:1, 1 Macc. 9:1 |

| Demetrius II Nicator | King of Asia | 145–138, 129 – 126 | Ruled over part of the kingdom, simultaneously with Antiochus VI and Tryphon. He was defeated by Antiochus VII, but regained the throne in 129 BCE. Mentioned in the Babylonian Astronomical Diaries.[91] | 1 Macc. 11:19, 1 Macc. 13:34 |

| Diodotus Tryphon | King of Asia | 142–138 | Usurped the throne after the death of Antiochus VI. Although Antiochus VII melted down most of his coins, some have been found in Orthosias.[78] | 1 Macc. 11:39, 1 Macc. 12:39 |

| Eumenes II Soter | King of Pergamom | 197–159 | Several of his letters have survived,[92] and he is mentioned by Polybius.[93] | 1 Macc. 8:8† |

| Heliodorus | Seleucid legate | fl. 178 | Identified in contemporary inscriptions.[94][95] | 2 Macc. 3:7, 2 Macc. 5:18 |

| Mithridates I | King of Parthia | 165–132 | Also called Arsaces.[83] He captured Demetrius II as recorded in the Babylonian Astronomical Diaries.[91] | 1 Macc. 14:2–3, 1 Macc. 15:22† |

| Perseus | King of Macedon | 179–168 | Son of Philip V.[96] Mentioned by Polybius.[97] and identified on his coins.[98] | 1 Macc. 8:5† |

| Philip II | King of Macedon | 359–336 | Father of Alexander the Great. Known from contemporary coins,[99] and mentioned by Aeschines.[65][66] | 1 Macc. 1:1, 1 Macc. 6:2† |

| Philip V | King of Macedon | 221–179 | His name appears on his coins,[100] and in Polybius' Histories.[101] | 1 Macc. 8:5† |

| Ptolemy IV Philopator | King of Egypt | 221–204 | Mentioned together with his wife and sister Arsinoe III in contemporary inscriptions from Syria and Phoenicia.[81] | 3 Macc. 1:1, 3 Macc. 3:12 |

| Ptolemy VI Philometor | King of Egypt | 180–145 | Referred to in ancient inscriptions,[102] and mentioned by Polybius.[103] | 1 Macc. 1:18, 2 Macc. 9:29 |

| Simon II | High Priest of Israel | Late 3rd century-early 2nd century | Praised in Sirach for his apparent role in repairing and fortifying the Temple in Jerusalem, also briefly mentioned in Josephus' Antiquities.[104] | 3 Macc. 2:1, |

New Testament

By far the most important and most detailed sources for first-century Jewish history are the works of Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (37 – c. 100 CE).[105][106] These books mention many of the same prominent political figures as the New Testament books and are crucial for understanding the historical background of the emergence of Christianity.[107] Josephus also mentions Jesus and the execution of John the Baptist[108] although he was not a contemporary of either. Apart from Josephus, information about some New Testament figures comes from Roman historians such as Tacitus and Suetonius and from ancient coins and inscriptions.

The central figure of the New Testament is Jesus of Nazareth. Despite ongoing debate concerning the authorship of many of its books, there is a consensus[14][109] among modern scholars that at least some were written by a contemporary of Jesus,[110][111] namely the epistles of Paul, parts of which are considered undisputed. However, outside the New Testament, no contemporary references to Jesus are known, unless a very early dating is assumed of some uncanonical gospel such as the Gospel of Thomas. Nevertheless, some authentic first century and many second century writings exist in which Jesus is mentioned,[n 6] leading many scholars to conclude that the historicity of Jesus is well established by historical documents.[112][113][114]

Gospels

| Name[n 7] | Title | Attestation and Notes | Biblical references [n 3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Augustus Caesar | Emperor of Rome | Reigned between 27 BCE and 14 CE, during which time Jesus was born. He left behind a wealth of buildings, coins and monuments,[115] including a funerary inscription in which he described his life and accomplishments. | Lk. 2:1† |

| Caiaphas | High Priest of Israel | In 1990, workers found an ornate limestone ossuary while paving a road in the Peace Forest south of the Abu Tor neighborhood of Jerusalem.[116][117] This ossuary appeared authentic and contained human remains. An Aramaic inscription on the side was thought to read "Joseph son of Caiaphas" and on the basis of this the bones of an elderly man were considered to belong to the High Priest Caiaphas.[116][118] In 2011, archaeologists from Bar-Ilan University announced the recovery of a stolen ossuary, It is inscribed with the text: "Miriam, daughter of Yeshua, son of Caiaphas, Priest of Ma’aziah from Beth ‘Imri". Based on it, Caiaphas can be assigned to the priestly course of Ma’aziah, instituted by King David. | Jn. 18:13 Jn. 11:49 Lk. 3:2 |

| Herod Antipas | Tetrarch of Galilee and Perea | A son of Herod the Great. Mentioned in Antiquities[119] and Wars of the Jews.[120] Both Matthew and Josephus record that he killed John the Baptist. | Lk. 3:1, Mt. 14:1 |

| Herod Archelaus | Ethnarch of Judea, Samaria and Edom | A son of Herod the Great. He is known from the writings of Flavius Josephus[119] and from contemporary coins.[121] | Mt. 2:22† |

| Herod the Great | King of Judea | Mentioned by his friend, the historian Nicolaus of Damascus.[122][123] His name is also found on contemporary Jewish coins.[121] | Mt. 2:1, Lk. 1:5 |

| Herodias | Herodian princess | The wife of Herod Antipas.[124] According to the synoptic gospels, she was formerly married to Antipas's brother Philip, apparently Philip the Tetrarch. However, Josephus writes that her first husband was Herod II. Many scholars view this as a contradiction, but some have suggested that Herod II was also called Philip.[125] | Mt. 14:3, Mk. 6:17 |

| Philip the Apostle | Bishop of Hierapolis | On Wednesday, 27 July 2011, the Turkish news agency Anadolu reported that archaeologists had unearthed a tomb that the project leader claims to be the tomb of Saint Philip during excavations in Hierapolis close to the Turkish city Denizli. The Italian archaeologist, Professor Francesco D'Andria stated that scientists had discovered the tomb within a newly revealed church. He stated that the design of the tomb, and writings on its walls, definitively prove it belonged to the martyred apostle of Jesus.[126] | Jn 12:21 Jn 1:43 |

| Philip the Tetrarch | Tetrarch of Iturea and Trachonitis | Josephus writes that he shared the kingdom of his father with his brothers Herod Antipas and Herod Archelaus.[127] His name and title appear on coinage from the period.[128][129] | Lk. 3:1 |

| Pontius Pilate | Prefect of Judea | He ordered Jesus' execution. A stone inscription was found that mentions his name and title: "[Po]ntius Pilatus, [Praef]ectus Iuda[ea]e" (Pontius Pilate, prefect of Judaea),[130][131] see Pilate Stone. He is mentioned by his contemporary Philo of Alexandria in his Embassy to Gaius (De Legatione ad Gaium, Περι αρετων και πρεσβειας προς Γαιον) | Mt. 27:2, Jn. 19:15–16 |

| Quirinius | Governor of Syria | Conducted a census while governing Syria as reported by Luke and Josephus,[132] and confirmed by a tomb inscription of one Quintus Aemilius Secundus, who had served under him.[133] | Lk. 2:2† |

| Tiberius Caesar | Emperor of Rome | Named in many inscriptions and on Roman coins. Among other accounts, some of his deeds are described by contemporary historian Velleius (died c. 31 CE).[134] | Lk. 3:1† |

| Salome | Herodian princess | A daughter of Herodias.[124] Although she is not named in the Gospels, but referred to as 'the daughter of Herodias', she is commonly identified with Salome, Herodias' daughter, mentioned in Josephus' Antiquities.[135] | Mt. 14:6, Mk. 6:22† |

| Simon Peter | Peter the Apostle | Mention by Ignatius of Antioch's Letter to the Romans and to the Smyrnaeans, Fragments from Papias's exposition of the oracles of the Lord, and the First Epistle to the Corinthians by Clement, who also says that Peter died as a martyr.[136][137][138][139] | Mt. 4:18-20, Mt. 16 |

Acts of the Apostles and Epistles

| Name[n 8] | Title | Attestation and Notes | Biblical references[n 3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ananias son of Nedebaios | High Priest of Israel | He held the office between c. 47 and 59 CE, as recorded by Josephus,[140] and presided over the trial of Paul. | Acts 23:2, Acts 24:1† |

| Antonius Felix | Procurator of Judea | Mentioned by historians Josephus,[141] Suetonius[142] and Tacitus[143] He imprisoned the apostle Paul around the year 58 CE, two years before Porcius Festus replaced him.[144] | Acts 23:24, Acts 25:14 |

| Apollos | Both Paul and Clement affirmed that he was a Christian in Corinth.[136] | 1 Cor 3:6 | |

| Aretas IV Philopatris | King of the Nabateans | According to Paul, Aretas' governor in Damascus tried to arrest him. Besides being mentioned by Josephus,[145] his name is found in several contemporary inscriptions[146] and on numerous coins.[147] | 2 Cor. 11:32† |

| Berenice | Herodian princess | A daughter of Herod Agrippa I. She appears to have had almost equal power to her brother Herod Agrippa II (with whom she was rumored to have an incestuous relationship, according to Josephus)[141] and is indeed called Queen Berenice in Tacitus' Histories.[148] | Acts 25:23, Acts 26:30 |

| Claudius Caesar | Emperor of Rome | Like other Roman emperors, his name is found on numerous coins[149] and monuments, such as the Porta Maggiore in Rome. | Acts 11:28, Acts 18:2† |

| Drusilla | Herodian princess | Married to Antonius Felix, according to the Book of Acts and Josephus' Antiquities.[141][150] | Acts 24:24† |

| Gallio | Proconsul of Achaea | Full name Lucius Iunius Gallio Annaeanus. Seneca, his brother, mentions him in his epistles.[151] In Delphi, an inscription, dated to 52 CE, was discovered that records a letter by emperor Claudius, in which Gallio is also named as proconsul[152] | Acts 18:12–17† |

| Gamaliel the Elder | Rabbi of the Sanhedrin | He is named as the father of Simon by Flavius Josephus in his autobiography.[153] In the Talmud he is also described as a prominent member of the Sanhedrin.[154] | Acts 5:34, Acts 22:3† |

| Herod Agrippa I | King of Judea | Although his name is given as Herod by Luke,[n 9] and as Agrippa by Josephus,[155] the accounts both writers give about his death are so similar that they are commonly accepted to refer to the same person.[22][156] Hence many modern scholars call him Herod Agrippa (I). | Acts 12:1, Acts 12:21 |

| Herod Agrippa II | King of Judea | He ruled alongside his sister Berenice. Josephus writes about him in his Antiquities,[141] and his name is found inscribed on contemporary Jewish coins.[121] | Acts 25:23, Acts 26:1 |

| John of Patmos | Mentioned by the Fragments of Papias of Hierapolis and by his contemporary Ignatius of Antioch[157][137] | Rev. 1 | |

| Judas of Galilee | Leader of a Jewish revolt. Both the Book of Acts and Josephus[132] tell of a rebellion he instigated in the time of the census of Quirinius.[158] | Acts 5:37† | |

| Nero Caesar | Emperor of Rome | Mentioned in Contemporary Coins,[159] Although he is not named in the Book of Revelation, the book mentions the number 666, theologians typically support the numerical interpretation that 666 is the equivalent of the name and title Nero[160] using the Hebrew numerology of gematria, and was used to secretly speak against the emperor. Also "Nero Caesar" in the Hebrew alphabet is נרון קסר NRON QSR, which when used as numbers represent 50 200 6 50 100 60 200, which add to 666. | Rev. 13:18, 2 Thes. 2:3† |

| Paul the Apostle | Mention by Ignatius of Antioch's Epistle to the Romans and Epistle to the Ephesians, Polycarp's Epistle to the Philippians, and in Clement of Rome's Epistle to the Corinthians, who also says that Paul Suffered martyrdom and that he had preached in the East and in the Far West[161][162][138][163] | Gal. 1, 1 Cor. 1 | |

| Porcius Festus | Governor of Judea | Succeeded Antonius Felix, as recorded by Josephus and the Book of Acts.[164][165] | Acts 24:27, Acts 26:25 |

Tentatively identified

These are Biblical figures for which tentative but likely identifications have been found in contemporary sources based on matching names and credentials. The possibility of coincidental matching of names cannot be ruled out however.

Hebrew Bible (Protocanonical Old Testament)

- Ahaziah/Amaziah, King of Judah. The Tel Dan Stele contains, according to many scholars, an account by a Syrian king (probably Hazael), claiming to have slain "[Ahaz]iahu, son of [... kin]g of the house of David", who reigned c. 850 – 849 BCE.[166][167] However, an alternative view, which dates the inscription half a century later, is that the name should be reconstructed as '[Amaz]iahu', who reigned c. 796–767 BCE.[168]

- Asaiah, servant of king Josiah (2 Kings 22:12). A seal with the text Asayahu servant of the king probably belonged to him.[169]

- Azaliah son of Meshullam, scribe in the Temple in Jerusalem: Mentioned in 2 Kings 22:3 and 2 Chronicles 34:8. A bulla reading "belonging to Azaliahu son of Meshullam." is likely to be his, according to archaeologist Nahman Avigad.[170]

- Azariah son of Hilkiah and grandfather of Ezra: Mentioned in 1 Chronicles 6:13,14; 9:11 and Ezra 7:1. A bulla reading Azariah son of Hilkiah is likely to be his, according to Tsvi Schneider.[171]

- Baalis king of Ammon is mentioned in Jeremiah 40:14. In 1984 an Ammonite seal, dated to c. 600 BCE, was excavated in Tell El-`Umeiri, Jordan that reads "belonging to Milkomor, the servant of Baalisha". Identification of 'Baalisha' with the biblical Baalis is likely,[172] but it is not currently known if there was only one Ammonite king of that name.[173]

- David, or more accurately his eponymous royal house, is mentioned in the Tel Dan Stele, see above entry for Ahaziah.

- Darius II of Persia, is mentioned by the contemporary historian Xenophon of Athens,[174] in the Elephantine Papyri,[38] and other sources. 'Darius the Persian', mentioned in Nehemiah 12:22, is probably Darius II, although some scholars identify him with Darius I or Darius III.[175][176]

- Gedaliah son of Ahikam, governor of Judah. A seal impression with the name 'Gedaliah who is over the house' is commonly identified with Gedaliah, son of Ahikam.[177]

- Gedaliah son of Pashhur, an opponent of Jeremiah. A bulla bearing his name was found in the City of David[178]

- Gemariah, son of Shaphan the scribe. A bulla was found with the text "To Gemaryahu ben Shaphan". This may have been the same person as "Gemariah son of Shaphan the scribe" mentioned in Jeremiah 36:10,12.[179]

- Geshem (Gusham) the Arab, mentioned in Nehemia 6:1,6 is likely the same person as Gusham, king of Kedar, found in two inscriptions in Dedan and Tell el-Mashkutah (near the Suez Canal)[180]

- Hilkiah, high priest in the Temple in Jerusalem: Mentioned throughout 2 Kings 22:8–23:24 and 2 Chronicles 34:9–35:8 as well as in 1 Chronicles 6:13; 9:11 and Ezra 7:1. Hilkiah in extra-biblical sources is attested by the clay bulla naming a Hilkiah as the father of an Azariah,[171] and by the seal reading Hanan son of Hilkiah the priest.[181]

- Isaiah, In February 2018 archaeologist Eilat Mazar announced that she and her team had discovered a small seal impression which reads "[belonging] to Isaiah nvy" (could be reconstructed and read as "[belonging] to Isaiah the prophet") during the Ophel excavations, just south of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.[182] The tiny bulla was found "only 10 feet away" from where an intact bulla bearing the inscription "[belonging] to King Hezekiah of Judah" was discovered in 2015 by the same team.[183] Although the name "Isaiah" in Paleo-Hebrew alphabet is unmistakable, the damage on the bottom left part of the seal causes difficulties in confirming the word "prophet" or a common Hebrew name "Navi", casting some doubts whether this seal really belongs to the prophet Isaiah.[184]

- Jehoram, King of Israel (c. 852 – 841 BCE) is probably mentioned in the Tel Dan inscription. According to the usual interpretation, the author of the text, probably Hazael, king of Syria,[185] claims to have slain both Ahaziah of Judah and "[Jeho]ram".[166][167] However, some scholars, reconstructing the pieces of the stela differently, do not see "[..]ram" as the name of an Israelite king.[186]

- Jehucal son of Shelemiah, an opponent of Jeremiah. Archaeologists excavated a bulla with his name,[187] but some scholars question the dating of the seal to the time of Jeremiah. According to Robert Deutsch the bulla is from the late 8th to early 7th century BCE, before the time of Jeremiah.

- Jerahmeel, prince of Judah. A bulla bearing his name was found.[188]

- Jeroboam (II), king of Israel. A seal belonging to 'Shema, servant of Jeroboam', probably refers to king Jeroboam II,[189] although some scholars think it was Jeroboam I.[173]

- Jezebel, wife of king Ahab of Israel. A seal was found that may bear her name, but the dating and identification with the biblical Jezebel is a subject of debate among scholars.[190]

- Josiah, king of Judah. Three seals were found that may have belonged to his son Eliashib.[191]

- Nathan-melech, one of Josiah's officials in 2 Kings 23:11. A clay bulla dated to the middle of the seventh or beginning of the sixth century B.C was found in March 2019 during the Givati Parking Lot dig excavation in the City of the David area of Jerusalem bearing the inscription, "(belonging) to Nathan-melech, servant of the king."[192][193]

- Nergal-sharezer, king of Babylon is probably identical to an official of Nebuchadnezzar II mentioned in Jeremiah 39:3, 13.[129] A record of his war with Syria was found on a tablet from the 'Neo-Babylonian Chronicle texts'.[194]

- Seraiah son of Neriah. He was the brother of Baruch. Nahman Avigad identified him as the owner of a seal with the name " to Seriahu/Neriyahu".[171]

- Shebna (or Shebaniah), royal steward of Hezekiah: only the last two letters of a name (hw) survive on the so-called Shebna lintel, but the title of his position ("over the house" of the king) and the date indicated by the script style, have inclined many scholars to identify the person it refers to with Shebna.[195]

- Sheshonq I, Pharaoh of Egypt, is normally identified with king Shishaq in the Hebrew Bible. The account of Shishaq's invasion in the 5th year of Rehoboam (1 Kings 14:25–28) is thought to correspond to an inscription found at Karnak of Shoshenq's campaign into Palestine.[196] However, a minority of scholars reject this identification.[197]

- Tou/Toi, king of Hamath. Several scholars have argued that Tou/Toi, mentioned in 2 Samuel 8:9 and 1 Chronicles 18:9, is identical with a certain 'Taita', king of 'Palistin', known from inscriptions found in northern Syria.[198][199] However, others have challenged this identification based on linguistic analysis and the uncertain dating of king Taita.[200]

- Uzziah, king of Judah. The writings of Tiglath-Pileser III may refer to him, but this identification is disputed.[201] There is also an inscription that refers to his bones, but it dates from the 1st century CE.

- Zedekiah, son of Hananiah (Jeremiah 36:12). A seal was found of "Zedekiah son of Hanani", identification is likely, but uncertain.[202]

Deuterocanonicals or biblical apocrypha

- Aretas I, King of the Nabataeans (fl. c. 169 BCE), mentioned in 2 Macc. 5:8, is probably referred to in an inscription from Elusa.[203]

New Testament

- 'The Egyptian', who was according to Acts 21:38 the instigator of a rebellion, also appears to be mentioned by Josephus, although this identification is uncertain.[204][205]

- Joanna, wife of Chuza An ossuary has been discovered bearing the inscription, "Johanna, granddaughter of Theophilus, the High Priest.",[206] It is unclear if this was the same Joanna since Johanna was the fifth most popular woman's name in Jewish Palestine.[207]

- Sergius Paulus was proconsul of Cyprus (Acts 13:4–7), when Paul visited the island around 46–48 CE.[208] Although several individuals with this name have been identified, no certain identification can be made. One Quintus Sergius Paulus, who was proconsul of Cyprus probably during the reign of Claudius (41–54 CE) is however compatible with the time and context of Luke's account.[208][209]

- Lysanias, was tetrarch of Abila around 28 CE, according to Luke (3:1). Because Josephus only mentions a Lysanias of Abila who was executed in 36 BCE, some scholars have considered this an error by Luke. However, one inscription from Abila, which is tentatively dated 14–29 CE, appears to record the existence of a later tetrarch called Lysanias.[210][211]

- Theudas. The sole reference to Theudas presents a problem of chronology. In Acts of the Apostles, Gamaliel, a member of the sanhedrin, defends the apostles by referring to Theudas (Acts 5:36–8). The difficulty is that the rising of Theudas is here given as before that of Judas of Galilee, which is itself dated to the time of the taxation (c. 6–7 AD). Josephus, on the other hand, says that Theudas was 45 or 46, which is after Gamaliel is speaking, and long after Judas the Galilean.

See also

Notes

- Identified in the Tel Dan Stele and the Deir Alla Inscription respectively.

- For kings and rulers these dates refer to their reigns. Dates for Israelite and Judahite kings are according to the chronology of Edwin R. Thiele.

- The dagger symbol (†) indicates that all occurrences in the Bible (including the Deuterocanonical books) have been cited.

- Names that are also mentioned in the Hebrew Bible are not repeated here.

- The official title for kings of the Seleucid dynasty

- These sources include (but are not limited to) 1st century: Paul, Peter, Josephus, Clement and the Synoptic Gospels; 2nd century: Tacitus, Lucian, Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, Hegesippus, Justin Martyr and a number of apocryphal works. For dates of the New Testament books, see Dating the Bible#Table IV: New Testament.

- Names that are also mentioned in the Old Testament are not repeated here.

- Names that are also mentioned in the Gospels are not repeated here.

- i.e. the author of the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles. See Authorship of Luke–Acts.

References

- Davies, Philip R., In Search of Ancient Israel: A Study in Biblical Origins, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015, p. 48

- Kelle, Brad E., Ancient Israel at War 853–586 BC, Osprey Publishing, 2007, pp. 8–9

- De Breucker, Geert, in The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture , edited by Karen Radner, Eleanor Robson, Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 643

- Kalimi, Isaac; Richardson, Seth (ed), Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem , Brill, 2014, p. 45

- Rainey, Anson F. "Stones for Bread: Archaeology versus History". Near Eastern Archaeology, Vol. 64, No. 3 (Sep., 2001), pp. 140–149

- Lawson Younger, K. "Kurkh Monolith". In Hallo, 2000, Vol. II p. 263

- Galil, G., The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah, Brill, 1996, p. 67

- Deutsch, Robert. "First Impression: What We Learn from King Ahaz's Seal". Biblical Archaeology Review, July 1998, pp. 54–56, 62

- Heilpern, Will (December 4, 2015). "Biblical King's seal discovered in dump site". CNN. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

- The palace of Apries, University College London, 2002

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders & Walker, J. H. (1909). The palace of Apries (Memphis II). School of Archaeology in Egypt, University College.

- Wolfram Grajetzki, Stephen Quirke, and Narushige Shiode (2000). Digital Egypt for Universities. University College London.

- Rogerson, John William; Davies, Philip R. (2005). The Old Testament world. Continuum International, 2005, p. 89.

- Dunn, James D. G. and Rogerson, John William (2003). Eerdmans commentary on the Bible]. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. "Artaxerxes": p. 321 ; "Pauline epistles": p. 1274

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Thomas Hobbes, Book 1, Chapter 137

- Lewis, D. M. and Boardman, John (1988). The Cambridge ancient history, Volume IV. Cambridge University Press. p. 149.

- Coogan et al., 2010, p. 673

- Oppenheim, A. L. in Pritchard 1969, pp. 294–301

- Harper, P. O.; Aruz, J.; Tallon, F. (1992). The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 270.

- Nabonidus Cylinder translation by Paul-Alain Beaulieu, author of The Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon 556–539 BC (1989).

- Oppenheim, A. L. in Pritchard 1969, p. 313

- Geoffrey W. Bromiley International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A–D. "Agrippa": p. 42; "Ben-Hadad III": p. 459

- Translation by Irving Finkel, at the British Museum

- Berlin, Adele and Brettler, Marc Zvi (2004). The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. p. 1243.

- Stead, Michael R. and Raine, John W. (2009). The Intertextuality of Zechariah 1–8. Continuum International. p. 40.

- Oppenheim, A. L. in Pritchard 1969, pp. 289–301

- Thompson, R. Campbell (1931). The prisms of Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal found at Nineveh. Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 25.

- Barton, George A. (1917). Archæology and the Bible. American Sunday-school Union. p. 381.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2003). The pantheon of Uruk during the neo-Babylonian period. Brill. pp. 151, 329.

- The Black Obelisk at the British Museum. Translation adapted by K. C. Hanson from Luckenbill, Daniel David (1927). Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia. Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hagelia, Hallvard (January 2004). "The First Dissertation of the Tel Dan Inscription". Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament. Volume 18, Issue 1, p. 136

- Oppenheim, A. L. in Pritchard 1969, pp. 287–288

- Cross, Frank Moore (March–April 1999). "King Hezekiah's Seal Bears Phoenician Imagery". Biblical Archaeology Review.

- Oppenheim, A. L. in Pritchard 1969, p. 284

- Tetley, M. Christine (2005). The reconstructed chronology of the Divided Kingdom. Eisenbrauns. p. 99.

- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of The People and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Earky Bronze Age to the fall of the Persians Empire. Routledge. p. 342

- Wiseman, D. J. (1991). Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon. Oxford University Press. pp. 81–82.

- Ginsburg, H. L. in Pritchard 1969, p. 492

- Oppenheim, A. L. in Pritchard 1969, p. 291

- The Annals of Tiglath-pileser. Livius.org. Translation into English by Leo Oppenheim. Quote: "I [Tiglath Pileser III] received tribute from... Menahem of Samaria...gold, silver, ...".

- Oppenheim, A. L. in Pritchard 1969, p. 283

- The Mesha Stele at the Louvre. Translation by K. C. Hanson (adapted from Albright 1969:320–21).

- Birch, Samuel and Sayce, A. H. (1873). Records of the past: being English translations of the Ancient monuments of Egypt and western Asia. Society of Biblical Archaeology. p. 13.

- "The Ishtar Gate", translation from "The Ishtar Gate, The Processional Way, The New Year Festival of Babylon". by Joachim Marzahn, Mainz am Rhein, Germany: Philipp von Zaubern, 1995.

- Boardman, John. The Cambridge ancient history. Vol. III Part 2. p. 408.

- Lipschitz, Oded (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah Under Babylonian Rule. Eisenbrauns. p. 80

- Greenspoon, Leonard (November 2007). "Recording of Gold Delivery by the Chief Eunuch of Nebuchadnezzar II". Biblical Archaeology Review. 33 (6): 18.

- "Nabu-sharrussu-ukin, You Say?". British Heritage. 28 (6): 8. January 2008. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- Oppenheim, A. L. in Pritchard 1969, p. 297

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2007). Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? New York: T&T Clark. p. 134

- Vanderkam, James C. (2001). An introduction to early Judaism. Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 7.

- "The Annals of Sargon Archived 2015-06-19 at the Wayback Machine". Excerpted from "Great Inscription in the Palace of Khorsabad", tr. Julius Oppert, in Records of the Past, vol. 9. London: Samuel Bagster and Sons, 1877. pp. 3–20.

- Reade, Julian (October 1975). "Sources for Sennacherib: The Prisms". Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Vol. 27, No. 4. pp. 189–196

- Lipiński, Edward et al. (1995). Immigration and emigration within the ancient Near East. Peeters Publishers & Department of Oriental Studies, Leuven. pp. 36–41, 48.

- Luckenbill, D. D. (April 1925). The First Inscription of Shalmaneser V. The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literature, Vol. 41, No. 3. pp. 162–164.

- Coogan et al., 2010, p. 1016

- Thomason, Allison Karmel (2004). "From Sennacherib's Bronzes to Taharqa's Feet: Conceptions of the Material World at Nineveh". Vol. 66. Papers of the 49th Rencontre Assriologique Internationale, Part One. pp. 151–162

- Coogan et al., 2010, p. 674

- Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. p. 487.

- Oppenheim, A. L. and Rosenthal, F. in Pritchard 1969, pp. 282–284, 655

- Fensham, Frank Charles (1982). The books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Eerdmans. p. 69.

- Briant, Pierre (2006). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns, 2006, p. 554.

- Schwartz, Daniel R. (2008). 2 Maccabees. Walter de Gruyter. p. 13

- Polybius, Book 33 Chapter 18

- Worthington, Ian, Alexander the Great: Man and God, Routledge, 2014, p. 66

- Aeschines, 3.219 Against Ctesiphon

- Mørkholm, O., Grierson, P.,, and Westermark, U. (1991). Early Hellenistic Coinage from the Accession of Alexander to the Peace of Apamaea (336–188 BC). Cambridge University Press. p. 42.

- Scolnic, Benjamin Edidin (2010). Judaism Defined: Mattathias and the Destiny of His People. University Press of America. p. 226.

- Polybius, Book 1 Chapter 3

- British Museum, # HPB, p150.1.C (in online collection)

- Champion, Craige B. (2004). Cultural Politics in Polybius’s Histories. University of California Press. p. 188.

- Polybius, Book 31 Chapter 21

- British Museum, # TC, p203.2.AntIV (in online collection)

- Grainger, John D. (1997). A Seleukid Prosopography and Gazetteer. Brill. p. 28. Citing Orientis Graeci Inscriptiones Selectae 252

- British Museum, # 1995,0605.73 (in online collection)

- Bartlett, J. R. (1973). The First and Second Books of the Maccabees. Cambridge University Press. p. 158.

- Bing, D. and Sievers, J. "Antiochus VI". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- Astin, A. E. (1989). The Cambridge Ancient History. Volume 8. Cambridge University Press. p. 369.

- Polybius, Book 21 Chapter 47

- Goodman, Martin; Barton, John; and Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary: The Apocrypha. Oxford University Press, 2001. p. 158.

- Gera, Dov (1998). Judaea and Mediterranean Politics: 219 to 161 B.C.E. Brill. p. 12.

- Cyrus takes Babylon (530 BCE)(Livius.org)

- Coogan et al., 2010, p. 1592

- Gruen, Erich S. (1986). The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome. Volume 1. University of California Press, 1986. p. 573. Citing Polybius, Book 30 Chapter 1

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings. Harvard University Press. p. 135.

- Salisbury, Joyce E. (2001). Encyclopedia of Women in the Ancient World. ABC-CLIO. pp. 55–57.

- Folmer, M. L. (1995). The Aramaic Language in the Achaemenid Period: A Study in Linguistic Variation. Peeters Publishers. pp. 27–28.

- Astin, A. E. (1989). The Cambridge Ancient History. Volume 8. Cambridge University Press. p. 358.

- Coogan et al., 2010, p. 1574

- Polybius, Book 31 Chapter 19

- Rahim Shayegan, M. (2011). Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia. Cambridge University Press. p. 68.

- Jonnes, L. and Ricl, M. (1997). A New Royal Inscription from Phrygia Paroreios: Eumenes II Grants Tryriaion the Status of a Polis. Epigraphica Anatolica. 1997, pp. 4–9.

- Geoffrey W. Bromiley (1982). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 199–200. Citing Polybius, Book 21 Chapter 45

- Schwartz, Daniel R. (2008). 2 Maccabees. Walter de Gruyter. p. 192. Citing Orientis Graeci Inscriptiones Selectae 247

- Coogan et al., 2010, p. 1604

- Coogan et al., 2010, p. 1576

- Thompson, Thomas L. and Wajdenbaum, Philippe (2014). The Bible and Hellenism: Greek Influence on Jewish and Early Christian Literature. Routledge. p. 203.

- British Museum, # 1968,1207.9 (in online collection)

- Warry, John (1991). Alexander 334–323 BC: Conquest of the Persian Empire. Osprey. p. 8.

- British Museum, # 1896,0703.195 (in online collection)

- Polybius, Book 4 Chapter 22

- Gera, Dov (1998). Judaea and Mediterranean Politics: 219 to 161 B.C.E. Brill. p. 12. Citing Orientis Graeci Inscriptiones Selectae 760

- Polybius, Book 39 Chapter 18

- Antiquities, B. XII, Chr. 4 § 10

- Grabbe, Lester L., An Introduction to First Century Judaism: Jewish Religion and History in the Second Temple Period, A&C Black, 1996, p. 22

- Millar, Fergus, The Roman Near East, 31 BC–AD 337, Harvard University Press, 1993, p. 70

- Feldman, Louis H., Josephus, the Bible, and History, Brill, 1989, p. 18

- Antiquities, Book XVIII Chr. 5 § 2

- Coogan et al., 2010, p. 1973

- Murphy-O'Connor, Jerome, Paul: a critical life, Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 4

- Cate, Robert L., One untimely born: the life and ministry of the Apostle Paul Mercer University Press, 2006, p. 48

- Levine, Amy-Jill ed., Allison, Dale C. Jr. ed., Crossan, John Dominic ed., The Historical Jesus in Context, Princeton University Press, 2008, "Most scholars agree that Jesus was baptized by John, (...) engaged in healings and exorcisms, taught in parables, (...) and was crucified by Roman soldiers during the governorship of Pontius Pilate (26–36 CE)"

- Stanton, Graham, The Gospels and Jesus Oxford University Press, 2nd ed. 2002, p. 145. He writes: "Today nearly all historians, whether Christians or not, accept that Jesus existed and that the gospels contain plenty of valuable evidence which has to be weighed and assessed critically."

- Bockmuehl, Markus N. A., The Cambridge companion to Jesus, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 124 "The fact that Jesus existed, that he was crucified under Pontius Pilate (...) seems to be part of the bedrock of historical tradition. If nothing else, the non-Christian evidence can provide us with certainty on that score"

- Augustus (Roman Emperor) in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael, eds. (1993). Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0195046458.

- Specter, Michael (August 14, 1992). "Tomb May Hold the Bones Of Priest Who Judged Jesus". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- Charlesworth, James H. (2006). Jesus and archaeology. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 323–329. ISBN 978-0802848802.

- Antiquities, B. XVII, Chr. 8, § 1

- Flavius Josephus, Wars of the Jews, translated by William Whiston, Book 2, Chr. 6, Par. 3

- Kanael, Baruch Ancient Jewish Coins and Their Historical Importance in The Biblical Archaeologist Vol. 26, No. 2 (May, 1963), p. 52

- Toher, Mark, in Herod and Augustus: Papers Presented at the IJS Conference, 21st-23rd June 2005 (edited by Jacobson, David M. & Kokkinos, Nikos), Brill, 2009, p. 71

- Nicolaus of Damascus, Autobiography, translated by C.M.Hall, fragment 134

- Antiquities, B. XVIII Chr. 5 § 4

- Hoehner, Harold W., Herod Antipas: A Contemporary of Jesus Christ, Zondervan, 1980, pp. 133–134

- "Tomb of Apostle Philip Found". biblicalarchaeology.org. 16 August 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Antiquities, B. XVII, Chr. 11 § 4

- Myers, E. A., The Ituraeans and the Roman Near East: Reassessing the Sources , Cambridge University Press 2010, p. 111

- Freedman, D.N. (ed), Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible , Wm. B. Eerdmans 2000, Philip the Tetrarch: p. 584, Nergal-Sharezer: p. 959

- Taylor, Joan E., Pontius Pilate and the Imperial Cult in Roman Judaea in New Testament Studies, 52:564–565, Cambridge University Press 2006

- Pilate Stone, translation by K. C. Hanson & Douglas E. Oakman

- Antiquities, B. XVIII Chr. 1 § 1

- Levick, Barbara, The Government of the Roman Empire: A Sourcebook , 2nd ed. Routledge 2000, p. 75

- Marcus Velleius Paterculus, Roman History, Book 2, Chr. 122

- Salome in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Letter to the Corinthians (Clement)

- From the exposition of the oracles of the Lord.

- The Epistle of Ignatius to the Romans

- The Epistle of Ignatius to the Smyrnaeans

- Antiquities, B. XX Chr. 5 § 2

- Antiquities, B. XX Chr. 7

- Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, The Twelve Caesars, translated by J. C. Rolfe, Book V, par. 28

- Cornelius Tacitus, Annals, translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb, Book XII Chr. 54

- Cate, Robert L., One Untimely Born: The Life and Ministry of the Apostle Paul, Mercer University Press, 2006, p. 117, 120

- Antiquities, B. XVIII Chr. 5 § 1

- Healey, John F., Textbook of Syrian Semitic Inscriptions, Volume IV: Aramaic Inscriptions and Documents of the Roman Period, Oxford University Press 2009, pp. 55–57, 77–79, etc.

- Galil, Gershon & Weinfeld, Moshe, Studies in Historical Geography and Biblical Historiography: Presented to Zechariah Kallai (Supplements to Vetus Testamentum), Brill Academic Publishers 2000, p. 85

- Cornelius Tacitus, The Histories, translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb, Book II, par. 2

- Burgers, P., Coinage and State Expenditure: The Reign of Claudius AD 41–54 in Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte Vol. 50, No. 1 (1st Qtr., 2001), pp. 96–114

- Borgen, Peder, Early Christianity and Hellenistic Judaism, T&T Clark, 1998, p. 55

- Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Letter 104 from Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium, translation by Richard M. Gummere

- Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, Gallio Inscription Archived 2011-05-18 at the Wayback Machine, translation by K. C. Hanson (adapted from Conzelmann and Fitzmyer).

- Flavius Josephus, The Life of Flavius Josephus, translated by William Whiston, paragraph 38.

- Gamaliel I in the Jewish Encyclopedia

- Antiquities, B. XVIII Chr. 6 § 1

- Bruce, F.F. The Book of Acts (revised), part of The New international commentary on the New Testament, Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1988

- Spurious Epistles of St. Ignatius of Antioch

- Kinman, Brent, Jesus' Entry Into Jerusalem: In the Context of Lukan Theology and the Politics of His Days, BRILL, 1995, p. 18

- Coinweek - NGC Ancients: Roman Coinage of Emperor Nero

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) by Peter M. Head, Tyndale Bulletin 51 (2000), pp. 1–16 http://www.tyndale.cam.ac.uk/Tyndale/staff/Head/NTOxyPap.htm#_ftn39 Archived 17 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- St Paul

- St. Polycarp

- The Epistle of Ignatius to the Ephesians

- Antiquities, Book XX, Chr. 8, § 9

- Yamazaki-Ransom, K., The Roman Empire in Luke's Narrative, Continuum, 2010, p. 145

- Dever, William G. (2017). Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah. SBL Press. p. 492. ISBN 9780884142171.

- Irvine, Stuart A. (2002). "The rise of the House of Jehu". In Dearman, J. Andrew; Graham, M. Patrick (eds.). The Land that I Will Show You: Essays on the History and Archaeology of the Ancient Near East in Honor of J. Maxwell Miller. A&C Black. pp. 113–115. ISBN 9780567355805.

- Becking, Bob E.J.H.; Grabbe, Lester, eds. (2010). Between Evidence and Ideology: Essays on the History of Ancient Israel Read at the Joint Meeting of the Society for Old Testament Study and the Oud Testamentisch Werkgezelschap Lincoln. Brill. p. 18. ISBN 9789004187375.

- Heltzer, Michael, THE SEAL OF ˓AŚAYĀHŪ. In Hallo, 2000, Vol. II p. 204

- Avigad, Nahman (1997). Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals (2 ed.). Institute of Archaeology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. p. 237. ISBN 978-9652081384.; WSS 90, published by the Israel Academy of Sciences & Humanities

- Schneider, Tsvi, Six Biblical Signatures: Seals and seal impressions of six biblical personages recovered', Biblical Archaeology Review, July/August 1991

- Grabbe, Lester L., Can a 'History of Israel' Be Written?, Continuum International, 1997, pp. 80–82

- Mykytiuk, Lawrence J., Identifying Biblical persons in Northwest Semitic inscriptions of 1200-539 B.C.E., Society of Biblical Literature, 2004, Baalis: p. 242 ; Jeroboam: p. 136

- Xenophon of Athens, Hellenica, Book 1, Chapter 2

- VanderKam, James C., From revelation to canon: studies in the Hebrew Bible and Second Temple literature, Volume 2000, Brill, 2002, p. 181

- Freedman, David N., The Unity of the Hebrew Bible, University of Michigan Press, 1993, p. 93

- Wright, G. Ernest, Some Personal Seals of Judean Royal Officials in The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 1, No. 2 (May, 1938), pp. 10–12

- Unique biblical discovery at City of David excavation site , Israel Ministry of Foreign affairs; 18-Aug-2008. Retrieved 2009-11-16

- Ogden, D. Kelly Bulla *2 "To Gemaryahu ben Shaphan", published by Brigham Young University. Dept. of Religious Education

- Wright, G. Ernest Judean Lachish in The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Feb., 1955), pp. 9–17

- Josette Elayi, New Light on the Identification of the Seal of Priest Hanan, son of Hilqiyahu (2 Kings 22), Bibliotheca Orientalis, 5/6, September–November 1992, 680–685.

- Mazar, Eilat. Is This the "Prophet Isaiah’s Signature?" Biblical Archaeology Review 44:2, March/April May/June 2018.

- In find of biblical proportions, seal of Prophet Isaiah said found in Jerusalem. By Amanda Borschel-Dan. The Times of Israel. 22 February 2018. Quote: "Chanced upon near a seal identified with King Hezekiah, a tiny clay piece may be the first-ever proof of the prophet, though a missing letter leaves room for doubt."

- "Isaiah’s Signature Uncovered in Jerusalem: Evidence of the prophet Isaiah?" By Megan Sauter. Bible History Daily. Biblical Archeology Society. 22 Feb 2018. Quote by Mazar: "Because the bulla has been slightly damaged at end of the word nvy, it is not known if it originally ended with the Hebrew letter aleph, which would have resulted in the Hebrew word for "prophet" and would have definitively identified the seal as the signature of the prophet Isaiah. The absence of this final letter, however, requires that we leave open the possibility that it could just be the name Navi. The name of Isaiah, however, is clear."

- http://theosophical.wordpress.com/2011/07/15/biblical-archaeology-4-the-moabite-stone-a-k-a-mesha-stele/

- Athas, George (2006). The Tel Dan Inscription: A Reappraisal and a New Introduction. A&C Black. pp. 240–242. ISBN 9780567040435.

- Clay seal connects to Bible in The Washington Times, Wednesday, October 1, 2008

- Avigad, Nahman, Baruch the Scribe and Jerahmeel the King's Son in The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 42, No. 2 (Spring, 1979), pp. 114–118

- Boardman, John, The Cambridge ancient history, Vol. 3 Part 1, p. 501

- Korpel, Marjo C.A., Scholars Debate “Jezebel” Seal, Biblical Archaeology Review

- Albright, W. F. in Pritchard 1969, p. 569

- Weiss, Bari.The Story Behind a 2,600-Year-Old Seal Who was Natan-Melech, the king’s servant?. New York Times. March 30, 2019

- 2,600-year old seal discovered in City of David. Jerusalem Post. April 1, 2019

- The Chronicle Concerning Year Three of Neriglissar, translation adapted from A. K. Grayson & Jean-Jacques Glassner

- Deutsch, Robert, Tracking Down Shebnayahu, Servant of the King in Biblical Archaeology Review May/Jun 2009

- Grabbe, Lester L., Israel in transition: from late Bronze II to Iron IIa (c. 1250–850 B.C.E.), Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010, p. 84

- Schreiber, N., The Cypro-Phoenician pottery of the Iron Age, Brill, 2003 p. 87

- Steitler, Charles (2010). "The Biblical King Toi of Ḥamath and the Late Hittite State "P/Walas(a)tin"". Bibische Notizen (146): 95.

- The History of King David in Light of New Epigraphic and Archeological Data, (link), website of University of Haifa, citing publications by Gershon Galil from 2013-2014

- Simon, Zsolt (2014). "Remarks on the Anatolian Background of the Tel Reḥov Bees and the Historical Geography of the Luwian States in the 10th c. BC". In Csabai, Zoltán (ed.). Studies in Economic and Social History of the Ancient Near East in Memory of Péter Vargyas. The University of Pécs, Department of Ancient History. pp. 724–725. ISBN 9789632367958.

- Haydn, Howell M. Azariah of Judah and Tiglath-Pileser III in Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 28, No. 2 (1909), pp. 182–199

- Day, John In search of pre-exilic Israel: proceedings of the Oxford Old Testament Seminar p. 376

- Healey, John F., The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus, Brill, 2001, p. 29

- Vanderkam, James C., in The Continuum History of Apocalypticism (edited by McGinn, Bernard J.; Collins, John J.; Stein, Stephen J.), Continuum, 2003, p. 133

- Frankfurter, David, Pilgrimage and Holy Space in Late Antique Egypt , Brill, 1998, p. 206

- D. Barag and D. Flusser, The Ossuary of Yehohanah Granddaughter of the High Priest Theophilus, Israel Exploration Journal, 36 (1986), 39–44.

- Richard Bauckham, Gospel Women: Studies of the Named Women in the Gospels (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2002), 143

- Gill, David W. J. (ed.) & Gempf, Conrad (ed.), The Book of Acts in Its Graeco-Roman Setting Wm. B. Eerdmans 1994, p. 282

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (ed.), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia Vol. III: K–P Wm. B. Eerdmans 1986, pp. 729–730 (entry Paulus, Sergius)

- Kerr, C. M., International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Wm. B. Eerdmans 1939, entry Lysanias

- Morris, Leon, Luke: an introduction and commentary Wm. B. Eerdmans 1988, p. 28

Bibliography

- Coogan, M. D.; Brettler, M. Z.; Newsom, C. A.; et al., eds. (2010). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195289602.

- Hallo, William W., ed. (1997–2002). The Context of Scripture. Brill. ISBN 9789004131057. OCLC 902087326. (3 Volumes)

- Flavius, Josephus. . Translated by Whiston, William.

- Polybius. Histories. Translated by Shuckburgh, Evelyn Shirley.

- Pritchard, James B., ed. (1969). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament with Supplement (3d ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691035031. OCLC 5342384.