Celsus

Celsus (/ˈsɛlsəs/; Hellenistic Greek: Κέλσος, Kélsos; fl. AD 175–177) was a 2nd-century Greek philosopher and opponent of early Christianity.[1][2][3] He is known for his literary work, On The True Doctrine (or Discourse, Account, Word; Hellenistic Greek: Λόγος Ἀληθής, Logos Alēthēs),[4][5] which survives exclusively in quotations from it in Contra Celsum, a refutation written in 248 by Origen of Alexandria.[3] On The True Doctrine is the earliest known comprehensive criticism of Christianity.[3] It was written between about 175[6] and 177,[7] shortly after the death of Justin Martyr (who was possibly the first Christian apologist), and was probably a response to his work.[6]

Celsus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Kélsos |

| Writing career | |

| Occupation | Philosopher |

| Language | Greek |

| Nationality | Roman Empire |

| Notable works | On The True Doctrine |

Work

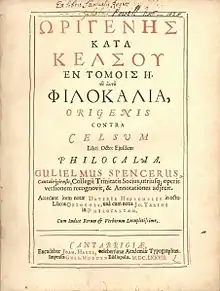

Celsus was the author of a work titled On the True Doctrine (Logos Alēthēs). The book was suppressed by the growing Christian community,[8] and banned in 448 AD by order of Valentinian III and Theodosius II, along with Porphyry's 15 books attacking the Christians, The Philosophy from Oracles, so no complete copies are extant,[4][5] but it can be reconstructed from Origen's detailed account of it in his 8 volume refutation, which quotes Celsus extensively.[4][7] Origen's work has survived and thereby preserved Celsus' work with it.[9]

Celsus seems to have been interested in Ancient Egyptian religion,[10] and he seemed to know of Hellenistic Jewish logos-theology, both of which suggest The True Doctrine was composed in Alexandria.[11] Celsus wrote at a time when Christianity was being persecuted.[12] Origen indicates that Celsus was an Epicurean living under the Emperor Hadrian.[13][14]

Celsus writes that "there is an ancient doctrine [archaios logos] which has existed from the beginning, which has always been maintained by the wisest nations and cities and wise men". He leaves Jews and Moses out of those he cites (Egyptians, Syrians, Indians, Persians, Odrysians, Samothracians, Eleusinians, Hyperboreans, Galactophagoi, Druids, and Getae), and instead blames Moses for the corruption of the ancient religion: "the goatherds and shepherds who followed Moses as their leader were deluded by clumsy deceits into thinking that there was only one God, [and] without any rational cause ... these goatherds and shepherds abandoned the worship of many gods". However, Celsus' harshest criticism was reserved for Christians, who "wall themselves off and break away from the rest of mankind".[6]

Celsus initiated a critical attack on Christianity, ridiculing many of its dogmas. He wrote that some Jews said Jesus' father was actually a Roman soldier named Pantera. Origen considered this a fabricated story.[15][16] In addition, Celsus addressed the miracles of Jesus, holding that "Jesus performed his miracles by sorcery (γοητεία)":[17][18][19]

O light and truth! he distinctly declares, with his own voice, as ye yourselves have recorded, that there will come to you even others, employing miracles of a similar kind, who are wicked men, and sorcerers; and Satan. So that Jesus himself does not deny that these works at least are not at all divine, but are the acts of wicked men; and being compelled by the force of truth, he at the same time not only laid open the doings of others, but convicted himself of the same acts. Is it not, then, a miserable inference, to conclude from the same works that the one is God and the other sorcerers? Why ought the others, because of these acts, to be accounted wicked rather than this man, seeing they have him as their witness against himself? For he has himself acknowledged that these are not the works of a divine nature, but the inventions of certain deceivers, and of thoroughly wicked men.[20][21]

Origen wrote his refutation in 248. Sometimes quoting, sometimes paraphrasing, sometimes merely referring, Origen reproduces and replies to Celsus' arguments. Since accuracy was essential to his refutation of The True Doctrine,[22] most scholars agree that Origen is a reliable source for what Celsus said.[23][24]

Biblical scholar Arthur J. Droge has written that it is incorrect to refer to Celsus' perspective as polytheism. Instead, he was an "inclusive" or "qualitative" monotheist, as opposed to the Jewish "exclusive" or "quantitative" monotheism;[6] historian Wouter Hanegraaff explains that "the former has room for a hierarchy of lower deities which do not detract from the ultimate unity of the One."[25] Celsus shows himself familiar with the story of Jewish origins.[26] Conceding that Christians are not without success in business (infructuosi in negotiis), Celsus wants them to be good citizens, to retain their own belief but worship the emperors and join their fellow citizens in defending the empire.[27] It is an earnest and striking appeal on behalf of unity and mutual toleration. One of Celsus' most bitter complaints is of the refusal of Christians to cooperate with civil society, and their contempt for local customs and the ancient religions. The Christians viewed these as idolatrous and inspired by evil spirits, whereas polytheists like Celsus thought of them as the works of the Daemons, or the god's ministers, who ruled mankind in his place to keep him from the pollution of mortality.[28] Celsus attacks the Christians as feeding off faction and disunity, and accuses them of converting the vulgar and ignorant, while refusing to debate wise men.[29] As for their opinions regarding their sacred mission and exclusive holiness, Celsus responds by deriding their insignificance, comparing them to a swarm of bats, or ants creeping out of their nest, or frogs holding a symposium round a swamp, or worms in conventicle in a corner of the mud.[30] It is not known how many were Christians at the time of Celsus (the Jewish population of the empire may have been about 6.6-10% in a population of 60 million to quote one reference).[31]

References

- Young, Frances M. (2006). "Monotheism and Christology". In Mitchell, Margaret M.; Young, Frances M. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Origins to Constantine. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 452–470. ISBN 978-0-521-81239-9.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Gottheil, Richard; Krauss, Samuel (1906). "CELSUS (Kέλσος)". Jewish Encyclopedia. Kopelman Foundation. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- Hoffmann p.29

- Ulrich R. Rohmer (15 January 2014). Ecce Homo: A collection of different views on Jesus. BookRix GmbH & Company KG. p. 98. ISBN 978-3-7309-7603-6.

- Hanegraaff p.22

- Chadwick, H., Origen: Contra Celsum, CUP (1965), p. xxviii

- Nixey, The Darkening Age, p. 32

- Origen, Contra Celsum, preface 4.

- Chadwick, H., Origen: Contra Celsum. CUP (1965), 3, 17, 19; 8, 58. He quotes an Egyptian musician named Dionysius in CC 6, 41.

- Chadwick, H., Origen: Contra Celsum, CUP (1965), p. xxviii-xxix

- Chadwick, H., Origen: Contra Celsum. CUP (1965), 8, 69

- Gottheil, Richard; Krauss, Samuel. "Celsus". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- Chadwick, H. Origen: Contra Celsum, introduction.

- Contra Celsum by Origen, Henry Chadwick, 1980, ISBN 0-521-29576-9, page 32

- Patrick, John, The Apology of Origen in Reply to Celsus, 2009, ISBN 1-110-13388-X, pages 22–24,

- Hendrik van der Loos (1965). The Miracles of Jesus. Brill Publishers. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

According to Celsus Jesus performed His miracles by sorcery (γοητεία); ditto in II, 14; II, 16; II, 44; II, 48; II, 49 (Celsus puts Jesus' miraculous signs on a par with those among men).

- Margaret Y. MacDonald (3 October 1996). Early Christian Women and Pagan Opinion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521567282. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

Celsus calls Jesus a sorcerer. He argues that the miracles of Jesus are on the same level as: 'the works of sorcerers who profess to do wonderful miracles, and the accomplishments of those who are taught by the Egyptians, who for a few obols make known their sacred lore in the middle of the market-place and drive daemons out of men and blow away diseases and invoke the souls of heroes, displaying expensive banquets and dining tables and cakes and dishes which are non-existent, and who make things move as though they were alive although they are not really so, but only appear as such in the imagination.'

- Philip Francis Esler (2000). The Early Christian World, Volume 2. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415164979. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

To disprove the deity of Christ required an explanation of his miracles which were recorded in scripture. Celsus does not deny the fact of Jesus' miracles, but rather concentrates on the means by which they were performed. Perhaps influenced by rabbinical sources, Celsus attributes Jesus' miracles to his great skills as a magician.

-

Ernest Cushing Richardson, Bernhard Pick (1905). The Ante-Nicene fathers: translations of the writings of the fathers down to A.D. 325, Volume 4. Scribner's. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

But Celsus, wishing to assimilate the miracles of Jesus to the works of human sorcery, says in express terms as follows: "O light and truth! he distinctly declares, with his own voice, as ye yourselves have recorded, that there will come to you even others, employing miracles of a similar kind, who are wicked men, and sorcerers; and Satan. So that Jesus himself does not deny that these works at least are not at all divine, but are the acts of wicked men; and being compelled by the force of truth, he at the same time not only laid open the doings of others, but convicted himself of the same acts. Is it not, then, a miserable inference, to conclude from the same works that the one is God and the other sorcerers? Why ought the others, because of these acts, to be accounted wicked rather than this man, seeing they have him as their witness against himself? For he has himself acknowledged that these are not the works of a divine nature, but the inventions of certain deceivers, and of thoroughly wicked men."

- Origen (30 June 2004). Origen Against Celsus, Volume 2. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 9781419139161. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

But Celsus, wishing to assimilate the miracles of Jesus to the works of human sorcery, says in express terms as follows: "O light and truth! he distinctly declares, with his own voice, as ye yourselves have recorded that there are as ye yourselves have recorded, that there will come to you even others, employing miracles of a similar kind, who are wicked men, and sorcerers; and he calls him who makes use of such devices, one Satan. So that Jesus himself does not deny that these works at least are not at all divine, but are the acts of wicked men; and being compelled by the force of truth, he at the same time not only laid open the doings of others, but convicted himself of the same acts. Is it not, then, a miserable inference, to conclude from the same works that the one is God and the other sorcerers? Why ought the others, because of these acts, to be accounted wicked rather than this man, seeing they have him as their witness against himself? For he has himself acknowledged that these are not the works of a divine nature; but the inventions of certain deceivers, and of thoroughly wicked men."

- James D. Tabor, The Jesus Dynasty: The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity, Simon and Schuster, 2006. p 64

- David Brewster & Richard R. Yeo, The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia, Volume 8, Routledge, 1999. p 362

- Bernhard Lang, International Review of Biblical Studies, Volume 54, Publisher BRILL, 2009. p 401

- Hanegraaff p.38

- Martin, Dale B. (2004). Inventing Superstition: From the Hippocratics to the Christians. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 141, 143. ISBN 0-674-01534-7.

- Terrot Reavely Glover, The Conflict Of Religions In The Early Roman Empire, (Methuen & Co., 1910 [Kindle Edition]), chap. VIII., p. 431

- Glover, p. 427

- Glover, p. 410

- Glover, p. 412

- Robert Louis Wilken, The Christians as the Romans Saw Them, (Yale: University Press, 2nd edition, 2003)

Sources

- Nixey, Catherine (2017). The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World. London, UK: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-5098-1606-4.

- Hanegraaff, Wouter (2012). Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521196215.

- R. Joseph Hoffmann (1987). On the True Doctrine: A Discourse Against the Christians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504151-4.

Further reading

- Theodor Keim, Gegen die Christen. (1873) [Celsus' wahres Wort], Reprint Matthes & Seitz, München 1991 (ISBN 3-88221-350-7)

- Pélagaud, Etude sur Celse (1878)

- K. J. Neumann's edition in Scriptores Graeci qui Christianam impugnaverunt religionem

- article in Hauck-Herzog's Realencyk. für prot. Theol. where a very full bibliography is given

- W. Moeller, History of the Christian Church, i.169 ff.

- Adolf Harnack, Expansion of Christianity, ii. 129 if.

- J. A. Froude, Short Studies, iv.

- Bernhard Pick, "The Attack of Celsus on Christianity," The Monist, Vol. XXI, 1911.

- Des Origenes: Acht Bücher gegen Celsus. Übersetzt von Paul Koetschau. Josef Kösel Verlag. München. 1927.

- Celsus: Gegen die Christen. Übersetzt von Th. Keim (1873) [Celsus' wahres Wort], Reprint Matthes & Seitz, München 1991 (ISBN 3-88221-350-7)

- Die »Wahre Lehre« des Kelsos. Übersetzt und erklärt von Horacio E. Lona. Reihe: Kommentar zu frühchristlichen Apologeten (KfA, Suppl.-Vol. 1), hrsg. v. N. Brox, K. Niederwimmer, H. E. Lona, F. R. Prostmeier, J. Ulrich. Verlag Herder, Freiburg u.a. 2005 (ISBN 3-451-28599-1)

- "Celsus the Platonist", Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Dr. B.A. Zuiddam, "Old Critics and Modern Theology", Dutch Reformed Theological Journal (South Africa), part xxxvi, number 2, June 1995.

- Stephen Goranson, "Celsus of Pergamum: Locating a Critic of Early Christianity", in D. R. Edwards and C. T. McCollough (eds), The Archaeology of Difference: Gender, Ethnicity, Class and the "Other" in Antiquity: Studies in Honor of Eric M. Meyers (Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research, 2007) (Information Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 60/61).

External links

- . Catholic Encyclopedia. 3. 1908.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.

"Celsus". The Jewish Encyclopedia. 1901–1906.

"Celsus". The Jewish Encyclopedia. 1901–1906.- Origen's Text on Celsus

- full text of The Arguments of Celsus Against the Christians in Google Books

- Works by Celsus at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Celsus at Open Library

- Works by Celsus at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)