Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera

Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera (/pænˈtɛrə/; c. 22 BC – AD 40) was a Roman soldier whose tombstone was found in Bingerbrück, Germany, in 1859. A historical connection from this soldier to Jesus has long been hypothesized by numerous scholars, based on the claim of the ancient Greek philosopher Celsus, who, according to Christian writer Origen in his "Against Celsus" (Greek Κατὰ Κέλσου, Kata Kelsou; Latin Contra Celsum), was the author of a work entitled The True Word (Greek Λόγος Ἀληθής, Logos Alēthēs).

Celsus' work was lost, but in Origen's account of it Jesus was depicted as the result of an affair between his mother Mary and a Roman soldier. He said she was "convicted of adultery and had a child by a certain soldier named Pantera".[1] Tiberius Pantera could have been serving in the region at the time of Jesus's conception.[1] Both the ancient Talmud and medieval Jewish writings and sayings reinforced this notion, referring to "Yeshu ben Pantera", which translates as "Jesus, son of Pantera". The hypothesis is considered unlikely by mainstream scholars given that there is little other evidence to support Pantera's paternity outside of the Greek and Jewish texts.[2][3]

Historically, the name Pantera is not unusual and was in use among Roman soldiers.[2][4]

Tombstone

Discovery

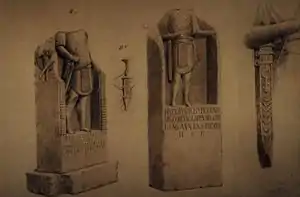

In October 1859, during the construction of a railroad in Bingerbrück in Germany, tombstones for nine Roman soldiers were accidentally discovered.[2] One of the tombstones was that of Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera and is presently kept in the Römerhalle museum in Bad Kreuznach, Germany.[5]

The inscription (CIL XIII 7514) on the tombstone of Abdes Pantera reads:[2][6][7]

|

|

Analysis

The name Pantera is Greek, although it appears in Latin in the inscription. It was perhaps his last name, and means panther.[2] The names Tiberius Julius are acquired names and were probably given to him in recognition of serving in the Roman army as he obtained Roman citizenship.[2] The name Abdes means "servant" or “slave” (Latinate form of Aramaic Abad) and suggests that Pantera had a generally Semitic or specifically Jewish background.[2] Pantera was from Sidonia, which is identified with Sidon in Phoenicia, and joined the Cohors I Sagittariorum (first cohort of archers).[2]

Pantera is not an unusual name, and its use goes back at least to the 2nd century.[4] Prior to the end of the 19th century, at various times in history scholars had hypothesized that the name Pantera was an uncommon or even a fabricated name, but in 1891 French archaeologist C. S. Clermont-Ganneau showed that it was a name that was in use in Iudaea by other people and Adolf Deissmann later showed with certainty that it was a common name at the time, and that it was especially common among Roman soldiers.[2][6][1]

At that time, Roman army enlistments were for 25 years and Pantera served 40 years in the army until his death at 62.[2] The reign of emperor Tiberius was between 14 and 37 and the Cohors I Sagittariorum was stationed in Judaea and then in Bingen. Pantera was probably the standard bearer (signifer) of his cohort.[1]

Hypothesis concerning a connection to Jesus

A connection between the two Panteras has been hypothesized by James Tabor. Tabor's theory hinges on the assumption that Celsus' information about Jesus' paternity was correct, and a soldier with this name, living at the right period, might have been Jesus' father. Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera's career would place him in Judea as a young man around the time of Jesus' conception.[1]

The Christian theologian Maurice Casey rejected Tabor's hypothesis and states that Tabor has presented no evidence.[3]

See also

References

- Tabor, James D. (2006). The Jesus Dynasty: A New Historical Investigation of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-8723-1.

- Whitehead, James; Burns, Michael (2008). The Panther: Posthumous Poems. Springfield, Mo.: Moon City Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 0-913785-12-1.

- Casey, Maurice (2011). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. London: T&T Clark. pp. 153-154. ISBN 0-567-64517-7.

- Evans, Craig A. (2003). The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: Matthew-Luke. 1. Colorado Springs, Colo.: Victor Books. p. 146. ISBN 0-7814-3868-3.

- Rousseau, John J.; Arav, Rami (1995). Jesus and His World: An Archaeological and Cultural Dictionary. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-8006-2903-8.

- Deissmann, Adolf; Strachan, Lionel R.M. (2003). Light From the Ancient East: The New Testament Illustrated by Recently Discovered Texts of the Graeco Roman World. Whitefish, Mont.: Kessinger Pub. pp. 73–74. ISBN 0-7661-7406-9.

- Campbell, J.B. (1994). The Roman Army, 31 BC-AD 337: A Sourcebook. Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 0-415-07173-9.