Central Boulevards of Brussels

The Central Boulevards (French: Boulevards du Centre, Dutch: Centrale Lanen) are a series of grand boulevards in central Brussels, Belgium. They were constructed following the covering of the river Senne (1867–71), as part of the major urban works by architect Léon Suys under the tenure of the city's then-mayor, Jules Anspach.[1] They are from south to north and from west to east: Maurice Lemonnier Boulevard, Anspach Boulevard, Adolphe Max Boulevard, and Émile Jacqmain Boulevard.[2]

_pr%C3%A8s_de_la_pl._Fontainas_-_panoramio.jpg.webp)

The covering of the Senne and the completion of the Central Boulevards allowed the construction of the modern public buildings which are central to downtown Brussels today, including the former Brussels Stock Exchange[3] and the Midi Palace,[4] as well as the reconstruction of the Greater Sluice Gate at the south of the city.

History

Origins: covering of the Senne

The Senne/Zenne (French/Dutch) was historically the main waterway of Brussels, but it became more polluted and less navigable as the city grew. By the second half of the 19th century, it had become a serious health hazard and was filled with pollution, garbage and decaying organic matter.[5] It flooded frequently, inundating the lower town and the working class neighbourhoods which surrounded it.[6]

Numerous proposals were made to remedy this problem, and in 1865, the then-mayor of the City of Brussels, Jules Anspach, selected a design by architect Léon Suys to cover the river and build a series of grand boulevards and public buildings.[1] The project faced fierce opposition and controversy, mostly due to its cost and the need for expropriation and demolition of working-class neighbourhoods.[7] The construction was contracted to a British company, but control was returned to the government following an embezzlement scandal.[8] This delayed the project, but it was still completed in 1871.[9]

The covering of the Senne brought boulevards to the heart of Brussels, whereas they had hitherto been limited to the small ring, a series of roadways built on the site of the 14th-century walls bounding the historic city centre. The boulevards, whose initial function was to go around the capital, thus became structural urban thoroughfares. The central boulevards' completion also allowed urban renewal and the construction along them of the modern public buildings of hausmannien style which are characteristic of downtown Brussels today.

Construction and development

The Central Boulevards—Hainaut Boulevard (now Maurice Lemonnier Boulevard), Central Boulevard (now Anspach Boulevard), North Boulevard (now Adolphe Max Boulevard), and Senne Boulevard (now Émile Jacqmain Boulevard)—were laid out between 1869 and 1871, and were progressively opened to traffic from 1871 to 1873.[9][2] The opening of these new routes offered a more efficient way to get into Brussels' lower town than the cramped streets of Rue du Midi/Zuidstraat, Rue des Fripiers/Kleerkopersstraat and Rue Neuve/Nieuwstraat and helped revitalise the lower quarters of the town.

In order to accomplish this revitalisation and attract investment, public buildings were constructed as part of Léon Suys' massive programme of beautification of the city centre, including the Brussels Stock Exchange (1868–73).[3] The vast Central Halls (French: Halles Centrales, Dutch: Centrale Hallen), a good example of metallic architecture, located between Rue des Halles/Hallenstraat and Rue de la Vierge Noire/Zwarte Lievevrouwstraat, replaced unhygienic open-air markets, though they were torn down in 1958.[10] The monumental fountain, which was to break the monotony of the boulevards at Fontainas Square, was abandoned for budgetary reasons.[9]

The construction of private buildings on the boulevards and surrounding areas took place later. The middle class continued to prefer living in new suburbs rather than the cramped areas of the city centre. The high prices of the land (expected to finance part of the construction costs) and the high rents were not within the means of the lower classes. Life in apartments was no longer desirable for residents of Brussels, who preferred to live in single family homes. The buildings constructed by private citizens had difficulty finding buyers.[11]

To give builders an incentive to create elaborate and appealing facades on their works, an architecture competition was arranged in which twenty buildings built before 1 January 1876 would win prizes. The first prize of 20,000 Belgian francs was awarded to Henri Beyaert who designed the Maison des Chats or Hier ist in den kater en de kat (loosely, "House of Cats") on North Boulevard.[12][13] Nonetheless, it took another 20 years, until 1895, for buildings to solidly line the boulevards.

Destruction of the old neighbourhood

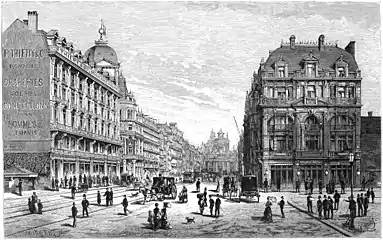

Destruction of the old neighbourhood Anspach Boulevard in 1880 (etching from L'Illustration nationale)

Anspach Boulevard in 1880 (etching from L'Illustration nationale) The Place de la Bourse and Anspach Boulevard in the 1920s

The Place de la Bourse and Anspach Boulevard in the 1920s

Contemporary history

The covering of the Senne and the construction of the Central Boulevards have left deep traces in the historic centre of Brussels. The formerly working-class districts have made way for apartment buildings and for the Stock Exchange with its commercial district, department stores, luxury hotels, concert halls, cafés and brasseries. From the end of the Second World War to the late 1970s, the Central Boulevards were subject to urban planners' failed attempts to transform them into urban motorways (see Brusselisation). In spite of this, they have mostly retained their 19th-century appearance to this day.[2]

Since 29 June 2015, the Central Boulevards have been pedestrianised between the Place de la Bourse/Beursplein and De Brouckère Square, as part of a broader pedestrianisation of Brussels' city centre (Le Piétonnier). The area, covering 50 hectares (120 acres), includes much of the historic centre within the small ring, such as the Grand Place, De Brouckère Square and Boulevard Anspach.[14][15][16]

The boulevards

Maurice Lemonnier Boulevard

Formerly named Hainaut Boulevard,[2] Maurice Lemonnier Boulevard stretches from South Boulevard to Fontainas Square. Interrupted halfway by Anneessens Square (location of the former Old Market), this artery is characterised by a homogeneous succession of low-rise buildings for the most part, bourgeois dwellings with a predilection for the neoclassical style, apartment buildings, and commercial buildings such as the Midi Palace.[4][17][18] In 1919, the city council ordered the boulevard to be renamed in honour of the alderman and patriot Maurice Lemonnier (1860–1930), who returned from a long captivity as a prisoner in Germany during World War I.[17] Some remarkable buildings along this relatively well-preserved stretch include the Midi Palace, the Model School (currently Charles Buls primary school), the municipal school no. 13 (currently Lucien Cooremans Institute) on Anneessens Square,[17] as well as the old Castellani rotunda (now transformed into a parking lot).[19][18]

Midi Palace on Lemonnier Boulevard

Midi Palace on Lemonnier Boulevard Lucien Cooremans Institute on Anneessens Square

Lucien Cooremans Institute on Anneessens Square Fontainas Square

Fontainas Square

Anspach Boulevard

Central by its original name as much as by its location, Anspach Boulevard connects Fontainas and De Brouckère squares.[20] In 1879, it was renamed in honour of Jules Anspach (1829–1879), the former mayor of the City of Brussels who instigated these works. Among the most important buildings on the Central Boulevards are concentrated there: the former Brussels Stock Exchange building,[3] major shops and entertainment venues, and formerly markets and department stores (Grand Bazar Anspach and Bourse Grands Stores). Large buildings, several of which bear the signature of the French promoter Mosnier, are adjacent to hotels (Grand Hotel and Central Hotel), cafés, cinemas, theatres, and concert halls (Pathé Palace cinema,[21] Bourse Theatre and Ancienne Belgique). Some remarkable buildings on this section include the former Stock Exchange on the Place de la Bourse/Beursplein, as well as Anspach Gallery.[20]

Anspach Gallery

Anspach Gallery Anspach Boulevard

Anspach Boulevard

Adolphe Max Boulevard

Unlike the other sections of the Central Boulevards, Adolphe Max Boulevard (formerly North Boulevard)[2] does not cover the Senne. It doubles with Emile Jacqmain Boulevard and connects De Brouckère Square to Botanical Garden Boulevard, forming a "Y" crossroad with Émile Jacqmain Boulevard.[22] It is characterised by five-level buildings on average, monumental in appearance for the most part. A dozen of them belong to the haussmannian vein in the Second Empire style. Others, of neoclassical inspiration, are distinguished by the decoration of their balconies, windows, and pediments.[23] In 1919, it was renamed in honour of the then-mayor of the City of Brussels, Adolphe Max (1869–1939). Remarkable buildings on this stretch include the House of Cats,[13] the entrance of the North Passage,[24] as well as the luxurious Hotel Le Plaza[25] and Hotel Atlanta.[26]

Hotel Le Plaza on Adolphe Max Boulevard

Hotel Le Plaza on Adolphe Max Boulevard

Émile Jacqmain Boulevard

Connecting De Brouckère Square to Botanical Garden and Antwerp boulevards, Émile Jacqmain Boulevard forms the western branch of the fork which marks the northern end of the Central Boulevards. Sumptuous in its time, the former Senne Boulevard (because it follows the course of the river)[2] was bordered by apartment buildings, commercial buildings, luxury hotels, town houses, and some bourgeois dwellings, which have now mostly been replaced by offices. Eclectic styles dominate with a good representation of the Second Empire. Functionalism and Art Deco are also represented by some buildings typical of the interwar period.[27]

AG Insurance building on Émile Jacqmain Boulevard

AG Insurance building on Émile Jacqmain Boulevard.jpg.webp) National Theatre on Émile Jacqmain Boulevard

National Theatre on Émile Jacqmain Boulevard

See also

References

- Map of Suys' Proposal. City Archives of Brussels: P.P. 1.169

- Eggericx 1997, p. 5.

- "La Bourse – Inventaire du patrimoine architectural". monument.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- "Palais du Midi – Inventaire du patrimoine architectural". monument.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- De Vries 2003, p. 26.

- Demey 1990, p. 42.

- Demey 1990, p. 61.

- De Vries 2003, p. 25.

- Demey 1990, p. 65.

- Demey 1990, p. 66.

- Demey 1990, p. 67.

- Demey 1990, p. 68.

- "Hier is't in den Kater en de Kat – Inventaire du patrimoine architectural". monument.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- O'Sullivan, Feargus (7 January 2014). "Europe's Most Congested City Contemplates Going Car-Free". City Lab. The Atlantic. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- Vermeersch, Laurent (6 February 2015). "Centrale lanen: twee fonteinen en twee fietsparkings" (in Dutch). Brussel Nieuws. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- "Project. Pedestrian zone". www.brussels.be. 2017-02-28. Retrieved 2018-12-15.

- "Boulevard Maurice Lemonnier – Inventaire du patrimoine architectural". monument.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- Eggericx 1997, p. 23.

- "Rotonde des panoramas". monument.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- Eggericx 1997, p. 26.

- "Pathé Palace – Inventaire du patrimoine architectural". monument.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- Eggericx 1997, p. 32.

- Eggericx 1997, p. 32–33.

- "Passage du Nord – Inventaire du patrimoine architectural". monument.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- "Hôtel Plaza – Inventaire du patrimoine architectural". monument.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- "Hôtel Atlanta – Inventaire du patrimoine architectural". monument.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- Eggericx 1997, p. 34.

Bibliography

- Demey, Thierry (1990). Bruxelles, chronique d’une capitale en chantier (in French). I: Du voûtement de la Senne à la jonction Nord-Midi. Brussels: Paul Legrain/CFC. OCLC 44643865.

- De Vries, André (2003). Brussels: A Cultural and Literary History. Oxford: Signal Books. ISBN 978-1-90266-946-5.

- Eggericx, Laure (1997). Bruxelles, ville d'Art et d'Histoire (in French). 20: Les Boulevards du Centre. Brussels: Centre d'information, de Documentation et d'Etude du Patrimoine.