Grand Place

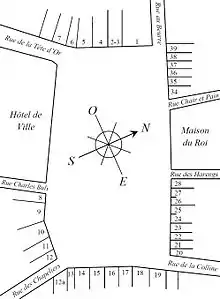

The Grand Place (French, pronounced [ɡʁɑ̃ plas]; "Grand Square"; also used in English[1]) or Grote Markt (Dutch, pronounced [ˌɣroːtə ˈmɑrkt] (![]() listen); "Grand Market") is the central square of Brussels, Belgium. It is surrounded by opulent guildhalls and two larger edifices, the city's Town Hall, and the King's House or Breadhouse (French: Maison du Roi, Dutch: Broodhuis) building containing the Brussels City Museum.[2][3][4] The square measures 68 by 110 metres (223 by 361 ft).

listen); "Grand Market") is the central square of Brussels, Belgium. It is surrounded by opulent guildhalls and two larger edifices, the city's Town Hall, and the King's House or Breadhouse (French: Maison du Roi, Dutch: Broodhuis) building containing the Brussels City Museum.[2][3][4] The square measures 68 by 110 metres (223 by 361 ft).

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

The Grand Place, with Brussels' Town Hall on the left | |

| Location | City of Brussels, Brussels-Capital Region, Belgium |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 857 |

| Inscription | 1998 (22nd session) |

| Area | 1.48 ha |

| Buffer zone | 20.93 ha |

| Coordinates | 50°50′48″N 4°21′9″E |

Location of the Grand Place  Grand Place (Belgium) | |

The Grand Place is the most important tourist destination and most memorable landmark in Brussels. It is also considered one of the most beautiful squares in Europe,[5][6][7] and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1998.[8]

History

Early history

In the 10th century, Charles, Duke of Lower Lorraine constructed a fort on Saint-Géry Island, the furthest inland point at which the Senne river was still navigable. This was the seed of what would become Brussels. By the end of the 11th century, an open-air marketplace was set up on a dried-up marsh near the fort that was surrounded by sandbanks. The market was called the Nedermerckt (meaning "Lower Market" in Old Dutch).[9]

The market likely developed around the same time as Brussels' commercial development. A document from 1174 mentions a lower market (Latin: forum inferius) not far from the port on the Senne river. The market was well situated along the Causeway (Dutch: Steenweg), an important commercial road which connected the prosperous regions of the Rhineland and the County of Flanders.

At the beginning of the 13th century, three indoor markets were built on the northern edge of the Grand Place; a meat market, a bread market, and a cloth market.[9] These buildings, which belonged to the Duke of Brabant, allowed the wares to be showcased even in bad weather, but also allowed the Dukes to keep track of the storage and sale of goods, in order to collect taxes. Other buildings, made of wood or stone, enclosed the Grand Place.

Rise in importance

Improvements to the Grand Place from the 14th century onwards would mark the rise in importance of local merchants and tradesmen relative to the nobility. As he was short on money, the Duke transferred control of mills and commerce to the local authorities. The city of Brussels ordered the construction of a large indoor cloth market, similar to those of the neighbouring cities of Mechelen and Leuven, to the south of the square. At this point, the Grand Place was still haphazardly laid out, and the buildings along the edges had a motley tangle of gardens and irregular additions.[9] The city expropriated and demolished a number of buildings that clogged the square, and formally defined its edges.

Brussels' Town Hall was built on the south side of the Grand Place in stages, between 1401 and 1455, and made it the seat of municipal power. Its spire towers 96 metres (315 ft) high, and is capped by a 4-metre (12 ft) statue of Saint Michael slaying a demon or devil. To counter this symbol of municipal power, from 1504 to 1536, the Duke of Brabant ordered a large building to be constructed across from the Town Hall as a symbol of ducal power.[9] It was erected on the site of the first cloth and bread markets, which were no longer in use, and it became known as the King's House (Middle Dutch: 's Conincxhuys) although no king has ever lived there. It is currently known as the Maison du Roi ("King's House") in French, but in Dutch, it continues to be called the Broodhuis ("Breadhouse"), after the market whose place it took. Over time, wealthy merchants and the increasingly powerful Guilds of Brussels built houses around the square.

The Grand Place witnessed many tragic events unfold during its history. In 1523, the first Protestant martyrs Henri Voes and Jean Van Eschen were burned by the Inquisition on the square. Forty years later, the counts of Egmont and Horn, who had spoken out against the policies of King Philip II in the Spanish Netherlands, were beheaded in front of the Breadhouse. This triggered the beginning of the armed revolt against Spanish rule, of which William of Orange took the lead.

Destruction and rebuilding

%252C_Augustin_Coppens_-_Ruins_on_part_of_the_Grand_Place_from_the_corner_of_the_Heuvelstraat_to_St_Nicholas.jpg.webp)

On 13 August 1695, a 70,000-strong French army under Marshal François de Neufville, duc de Villeroy, began a bombardment of Brussels in an effort to draw the League of Augsburg's forces away from their siege on French-held Namur in what is now southern Belgium. The French launched a massive bombardment of the mostly defenseless city centre with cannons and mortars, setting it on fire and flattening the majority of the Grand Place and the surrounding city. Only the stone shell of the town hall and a few fragments of other buildings remained standing. That the town hall survived at all is ironic, as it was the principal target of the artillery fire.

The Grand Place was rebuilt in the following four years by the city's guilds. Their efforts were regulated by the city councillors and the Governor of Brussels, who required that their plans be submitted to the authorities for approval. This helped to deliver a remarkably harmonious layout for the rebuilt square, despite the ostensibly clashing combination of Gothic, Baroque and Louis XIV styles.

During the following two centuries, the Grand Place underwent significant damage. In the late 18th century, Brabant Revolutionaries sacked it, destroying statues of nobility and symbols of Christianity.[10] The guildhalls were seized by the state and sold. The buildings were neglected and left in poor condition, with their facades painted, stuccoed and damaged by pollution.

By the late 19th century, a sensitivity arose about the heritage value of the buildings – the turning point was the demolition of L'Étoile guild house in 1852. Under the impulse of then-mayor Charles Buls, Brussels' authorities had the Grand Place returned to its former splendour, with buildings restored or reconstructed. In 1856, a monumental fountain commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the reign of King Leopold I was installed in the centre of the square. It was replaced in 1860 by a fountain surmounted by statues of the Counts of Egmont and Horn, which was erected in front of the King's House and later moved to the Small Sablon. Thirty years later, during the Belle Époque, a bandstand was raised in its place. In 1885, the Belgian Labour Party (POB-BWP), the first socialist party in Belgium, was founded during a meeting at the Grand Place.

20th and 21st centuries

At the start of World War I, as refugees flooded Brussels, the Grand Place was filled with military and civilian casualties.[11] The Town Hall served as a makeshift hospital.[11] On 20 August 1914, at 2 p.m., the occupying German army arrived at the Grand Place and set up field kitchens.[11] The occupiers hoisted a German flag at the left side of the Town Hall.[11]

The Grand Place continued to serve as a market until 19 November 1959, and it is still called the Grote Markt ("Grand Market") in Dutch. Neighbouring streets still reflect the area's origins, named after the sellers of butter, cheese, herring, coal, and so on. In 1979, the Grand Place was bombed.[12] In 1990, the square was pedestrianised and it is currently part of a large pedestrian zone in the centre of Brussels.[13]

The Grand Place was named by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1998.[8] The place is now primarily an important tourist attraction. A number of guild houses have been converted into shops, terraced restaurants and brasseries. Notable institutions include Godiva Chocolatier and the Maison Dandoy speculoos confectionery. One of the houses owned by the brewers' guild is home to a brewers' museum.

The Grand Place was voted the most beautiful square in Europe in 2010. A survey by a Dutch website[5] asked its users to rate different squares across Europe. Moscow's Red Square and the Place Stanislas in Nancy, France, took second and third place.

Buildings around the square

Town Hall

The Town Hall (French: Hôtel de Ville, Dutch: Stadhuis) is the central edifice on the Grand Place. It was built in several stages between 1401 and 1455 and is also the square's only remaining medieval building.[14] The architect and designer is probably Jean Bornoy with whom Jacob van Thienen collaborated. The young Duke Charles the Bold laid the first stone of the west wing in 1444. The architect of this part of the building is unknown. Historians think that it could be William (Willem) de Voghel who was the architect of the city of Brussels in 1452, and who was also, at that time, the designer of the Aula Magna at the Palace of Coudenberg. The 96-metre-high (315 ft) tower in Brabantine Gothic style is the work of the architect Jan van Ruysbroek.[15] At its summit, stands a 5-metre-tall (16 ft) gilt metal statue of Saint Michael, the patron saint of Brussels, slaying a dragon or demon.

The Town Hall is asymmetrical, since the tower is not exactly in the middle of the building and the left part and the right part are not identical (although they seem at first sight). According to a legend, the architect of the building, upon discovering this "error", leapt to his death from the tower. More likely, the asymmetry of the Town Hall was an accepted consequence of the scattered construction history and space constraints.

King's House

_Brussels_City_Museum_Aug_2009.jpg.webp)

As early as the 12th century, the King's House (French: Maison du Roi) was a wooden building where bread was sold, hence the name it kept in Dutch; Broodhuis (Bread House or Bread Hall). The original building was replaced in the 15th century by a stone building which housed the administrative services of the Duke of Brabant, which is why it was first called the Duke's House, and when the same duke became King of Spain, it was renamed the King's House. In the 16th century, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V ordered to rebuild it in a late Gothic style very similar to the contemporary design, although without towers or galleries.

Because of the damage suffered over time, especially during the bombardment of 1695, the city had the King's House rebuilt in 1873 by architect Victor Jamaer in the Gothic Revival style. The current building, whose interior was renovated in 1985, has housed the Brussels City Museum since 1887.[2][3][4]

Houses of the Grand Place

The Grand Place is lined on each side with a number of guild houses and a few private houses. In their current form, they are largely the result of the reconstruction after the bombardment of 1695. The strongly structured facades with their rich sculptural decoration including pilasters and balustrades and their lavishly designed gables are based on Italian Baroque with some Flemish influences.

Between Rue de la Tête d'or/Guldenhoofdstraat and Rue au Beurre/Boterstraat (west):

.jpg.webp)

- № 1: Le Roy d'Espagne (Dutch: Den Coninck van Spaigniën; "The King of Spain"), House of the Corporation of Bakers, built in 1696.[16] Originally, the three bays to the right of the entrance formed an independent house (Saint-Jacques), accessible through a door located on Rue au Beurre/Boterstraat. The very dilapidated building was completely rebuilt in 1901–1902. It is decorated with busts of Saint Aubert (patron saint of bakers) and Charles II of Spain.

- № 2–3: La Brouette (Dutch: Den Cruywagen; "The Wheelbarrow"), House of the Corporation of Greasers since the 15th century, built in stone in 1644. The facade partly resisted the bombardment of 1695 and was rebuilt in 1697 under the direction of Jean Cosyn.[17] Decorated with a statue of Saint Giles (patron saint of greasers), it was restored in 1912. The left door opened into a now disappeared alleyway that led onto Rue au Beurre.

- № 4: Le Sac (Dutch: Den Sack; "The Bag"), House of the Corporation of Carpenters, whose tools decorate the facade since the 15th century. Built in stone in 1644, partly spared by the bombardment, it was rebuilt (from the third floor up) by the carpenter Antoine Pastorana in 1697.[18] The sculptures from this rebuilding are the work of Peter Van Dievoet et Laurent Merkaert.[19] This house was restored in 1912 by the architect Jean Seghers. Nowadays, a Starbucks coffee shop is located on the ground floor of this building.

- № 5: La Louve (Dutch: Den Wolf or Den Wolvin; "The She-Wolf"), House of the Oath of Archers, built in 1690 by Pierre Herbosch.[20] In 1696, the facade was rebuilt with a horizontal cornice, surmounted by a base where a statue was placed of a Phoenix rising from the ashes, symbol of the reconstruction of the city after the bombardment. The decorated pediment of Apollo was restored in 1890–1892 by the architect of the city of Brussels, Victor Jamaer, according to the original drawings. The bas-relief represents Romulus and Remus suckling the she-wolf.

- № 6: Le Cornet (Dutch: Den Horen; "The Cornet"), House of the Corporation of Boatmen since the 15th century, rebuilt in 1697 by Antoine Pastorana who drew its gable in the shape of a ship stern.[21] The sculptures are by Peter van Dievoet, and by a contract passed on 3 April 1697, the deans of the Trade of Boatmen entrusted Peter van Dievoet with the execution of the whole sculpting of the facade. The building was restored from 1899 to 1902.

- № 7: Le Renard (Dutch: In den Vos; "The Fox"), House of the Corporation of Haberdashers since the 15th century, rebuilt in 1699.[22] It contains bas-reliefs above the ground floor, allegorical sculptures of the four continents, and at the top, a (now disappeared) statue of Saint Nicholas, patron of haberdashers.

Between Rue Charles Buls/Karel Bulsstraat and Rue des Chapeliers/Hoedenmakersstraat (south):

- № 8: L'Étoile (Dutch: De Sterre; "The Star"), House of the Amman, rebuilt in 1695. It was demolished in 1852 with the whole side of the street which corner it occupies, and which was then called Rue de l'Étoile/Sterrestraat, to allow the passage of a horse-drawn tramway. Rebuilt in 1897, at the initiative of then-mayor of Brussels, Charles Buls, by replacing the ground floor with a colonnade, it became an annex to the neighbouring house. The street was renamed Rue Charles Buls/Karel Bulsstraat in honour of the mayor and plaque is affixed under the house, next to the monument to Everard t'Serclaes, in tribute to him as well as to the builders of the Grand Place.

- № 9: Le Cygne (Dutch: De Zwane; "The Swan"), bourgeois house rebuilt in 1698 by financier Pierre Fariseau whose monogram is placed in the centre of the facade.[23] It was bought in 1720 by the Corporation of Butchers who modified the upper part. Restored between 1896 and 1904. The founding congress of the Belgian Workers' Party was held there in April 1885. It is also in this house that Karl Marx wrote the Manifesto of the Communist Party.

- № 10: L'Arbre d'Or (Dutch: In den Gulden Boom; "The Golden Tree"), House of the Corporation of Brewers (now converted into a brewery museum). It is dated 1696 and was restored in 1901.[24] During the construction of this house, the architect Guillaume de Bruyn pronounced the famous sentence: "You had the conscience to work for eternity!". This house is adorned with sculptures by Marc de Vos and Peter van Dievoet and is capped by an equestrian statue of Charles Alexander of Lorraine, which was installed in 1752 to replace another of Maximilian II Emmanuel of Bavaria, governor during the reconstruction of Brussels.

- № 11: La Rose (Dutch: De Roos; "The Rose"), private house rebuilt in 1702 and restored in 1901.[25]

- № 12: Le Mont Thabor (Dutch: In den Bergh Thabor; "The Mount Thabor"), private house rebuilt in 1699 and restored in 1885.[26]

Between Rue des Chapeliers/Hoedenmakersstraat and Rue de la Colline/Bergstraat (east):

- № 12a (formerly № 2–4 rue des Chapeliers/Hoedenmakersstraat): House of Alsemberg (French: Maison d'Alsemberg) or House of the King of Bavaria (French: Maison du Roi de Bavière, Dutch: De Koning van Beieren), private house built in 1699 with a blue stone portal bearing the mark of the stonemason and a large oculus on the gable.[27]

- № 13–19: House of the Dukes of Brabant (French: Maison des Ducs de Brabant, Dutch: Huis van de Hertogen van Brabant), set of seven houses grouped behind the same monumental facade designed by Guillaume de Bruyn and modified in 1770, so called because of the busts of the Dukes of Brabant which adorn it.[28] It was restored between 1881 and 1890.

- № 13: La Renommée (Dutch: De Faem; "The Fame"), private house

- № 14: L'Ermitage (Dutch: De Cluyse; "The Hermitage"), House of the Corporation of Carpet Makers

- № 15: La Fortune (Dutch: De Fortuine; "The Fortune"), House of the Corporation of Tanners

- № 16: Le Moulin à Vent (Dutch: De Windmolen; "The Windmill"), House of the Corporation of Millers

- № 17: Le Pot d'Étain (Dutch: De Tinnepot; "The Tin Pot"), House of the Corporation of Cartwrights

- № 18: La Colline (Dutch: De Heuvel; "The Hill"), House of the Corporation of Sculptors, Masons, Stone-Cutters and Slate-Cutters

- № 19: La Bourse (Dutch: De Borse; "The Purse"), private house

Between Rue de la Colline/Bergstraat and Rue des Harengs/Haringstraat (north-east):

- № 20: Le Cerf (Dutch: De Hert or De Heert; "The Deer"), private house. The facade was rebuilt in 1710 and restored in 1897.[29]

- № 21–22: Joseph et Anne (Dutch: Joseph en Anna; "Joseph and Anne"), two private houses under a single facade.[30] The gable, destroyed in the 19th century, was rebuilt in 1897 after a watercolour by Ferdinand-Joseph De Rons from 1729.

- № 23: L'Ange (Dutch: Den Engel; "The Angel"), private house of the merchant Jan De Vos, rebuilt in 1697 after a drawing by Guillaume de Bruyn who restored the Italian-Flemish style.[31] The altered facade was reconstructed in 1897 according to old images.

- № 24–25: La Chaloupe d'Or (Dutch: De Gulden Boot; "The Golden Boat"), House of the Corporation of Tailors, designed by William de Bruyn in 1697.[32] It was destined to become the centre of a monumental facade covering the entire north-eastern side, which was refused by the owners of the neighbouring houses. It is capped by a statue of Saint Homobonus of Cremona, patron saint of tailors. The sculptures are the work of Peter van Dievoet. The current bust of Saint Barbara above the door is the work of Godefroid Van den Kerckhove (1872).

- № 26–27: Le Pigeon (Dutch: De Duif; "The Dove") was the property of the Corporation of Painters since the 15th century, who sold it in 1697 to the stonemason and architect Pierre Simon, considered to be the designer of the facade.[33] It housed Victor Hugo during his stay in Brussels and was restored in 1908.

- № 28: Le Marchand d'Or (Dutch: De Gulden Koopman; "The Golden Merchant"), private house of the tiler Corneille Mombaerts, rebuilt in 1709 and restored in 1882.[34]

Between Rue Chair et Pain/Vlees-en-Broodstraat and Rue au Beurre/Boterstraat (north-west):

- № 34: Le Heaume (Dutch: Den Helm; "The Helmet"), private house.[35] According to Guillaume Des Marez, the architect is Peter van Dievoet. It was restored in 1920.

- № 35: Le Paon (Dutch: Den pauw; "The Peacock"), surmounted by a characteristic gable of 18th-century houses.[36] It was restored in 1882.

- № 36–37: Le Petit Renard (Dutch: t Voske; "The Small Fox") or Le Samaritain (Dutch: De Samaritaen; "The Samaritan") and Le Chêne (Dutch: Den Eyck; "The Oak"), two houses dated 1696 and restored in 1884–1886.[37]

- № 38: Sainte-Barbe (Dutch: In Sint Barbara; "Saint Barbara"), private house built in 1696.[38]

- № 39: L'Âne (Dutch: Den Ezel; "The Donkey"), private house restored in 1916.[39]

Events

Festivities and cultural events are frequently organised on the Grand Place, such as light and sound shows during the Christmas period as part of the "Winter Wonders", or concerts in the summer. Among the most important and famous are the Flower Carpet and the Ommegang.

Flower carpet

Every two years[40] in August, an enormous flower carpet is set up in the Grand Place for a few days. A million colourful begonias are set up in patterns, and the display covers a full 24 by 77 metres (79 by 253 ft), for area total of 1,800 m2 (19,000 sq ft).[9] The first flower carpet was made in 1971, and due to its popularity, the tradition continued, with the flower carpet attracting a large number of tourists.[41]

Ommegang

Twice a year, at the turn of June and July, the Ommegang of Brussels, one of the largest historical reenactments in Europe, commemorating the Joyous Entry of Emperor Charles V and his son Philip II in Brussels in 1549, ends with a large spectacle on the Grand Place.

In popular culture

Filmography

- The second and third series of the BBC television series Secret Army were filmed there in 1978 and 1979, specifically around the building that is now Maxim's restaurant.

Gallery

The Grand Place in 1887 by Christiaan Dommershuijzen

The Grand Place in 1887 by Christiaan Dommershuijzen.jpg.webp) The Grand Place, towards the King's House

The Grand Place, towards the King's House The Grand Place on the day of the "Belgian Beer Weekend"

The Grand Place on the day of the "Belgian Beer Weekend" The Grand Place in the evening

The Grand Place in the evening Brussels' Town Hall in the evening

Brussels' Town Hall in the evening.jpg.webp) Everard t'Serclaes memorial

Everard t'Serclaes memorial.jpg.webp) Panoramic view

Panoramic view

See also

- History of Brussels

- Bombardment of Brussels

- Peter van Dievoet (Sculptor and Architect)

References

- In this case, the French word place is a "false friend", and the correct counterparts in English are "plaza" or "town square".

- "Welcome - Brussels City Museum". www.brusselscitymuseum.brussels (in French). Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- "Museums and art centres". www.brussels.be. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- "Brussels City Museum - Exhibitions, Hours, Tickets". www.brussels.info. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- "Most Beautiful Squares in Europe". stedentripper.com. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- "The 10 MOST BEAUTIFUL SQUARES in the World | The Grandest Monumental City Squares and Town Plazas". www.ucityguides.com. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- "The world's most beautiful city squares - perfect places for people-watching". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "La Grand-Place, Brussels". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- "History of the Grand Place of Brussels". Commune Libre de l'Îlot Sacré. Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- "La Grande-Place de Bruxelles" (in French). bruNET. May 17, 2007. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- "Occupation of Brussels on 20 August 1914". City of Brussels. City of Brussels. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- "I.r.a. Sets Off Bomb at Belgian Concert". August 29, 1979 – via NYTimes.com.

- "Pedestrian zone". www.brussels.be. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- Paul F. State (April 16, 2015). Historical Dictionary of Brussels. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 208–. ISBN 978-0-8108-7921-8.

- André De Vries (2003). Brussels: A Cultural and Literary History. Signal Books. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-902669-47-2.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Den Coninck van Spaigniën - Grote Markt 1 - SAMYN A. (1900)". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Den Cruywagen - Grote Markt 2-3 - COSIJN J. (1697)". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Den Sack - Grote Markt 4 - PASTORANA A. (1697)". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- Guillaume Des Marez, Guide illustré de Bruxelles, Brussels, 1928

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - De Wolf / De Wolvin - Grote Markt 5 - HERBOSCH P." www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Den Horen / Schippershuis - Grote Markt 6 - PASTORANA A." www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - In den Vos - Grote Markt 7 - JAMAER P.V. (1883)". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - De Sterre / De Zwane - Grote Markt 9 - Karel Bulsstraat 2". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - De Hille / In den Gulden Boom - Grote Markt 10 - Brouwersstraat 12 - DE BRUYN W." www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - De Roos - Grote Markt 11 - JAMAER P.V. (1885)". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - In den Berg Thabor - Grote Markt 12 - TIMMERMANS F." www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - De Koning van Beieren - Grote Markt 12a - Hoedenmakersstraat 2-4". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Hertogen van Brabant - Grote Markt 13, 14, 15, 16, 17-18, 19 - DE BRUYN W." www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Heert - Grote Markt 20". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Joseph / Anna - Grote Markt 21-22 - SAMYN A. (1896)". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Den Engel - Grote Markt 23". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - De Gulden Boot / De Mol - Grote Markt 24-25 - DE BRUYN W." www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - De Duif - Grote Markt 26, 27 - SEGERS J." www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Gulden Koopman / De Wapens van Brabant - Haringstraat 20 - Grote Markt 28 - WALCKIERS J." www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Den Helm - Grote Markt 34". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Den Pauw - Grote Markt 35 - JAMAER P.V. (1882)". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - T Voske / Den Eyck - Grote Markt 36, 37 - JAMAER P.V." www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - In Sint Barbara - Grote Markt 38 - MALFAIT F." www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Brussel Vijfhoek - Den Ezel - Grote Markt 39". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- Kemp, Richard (1997) [1991]. "Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg". The Picture Atlas of the World (Third ed.). 9 Henrietta Street, London: Dorling Kindersley. p. 41. ISBN 0-7513-5358-2.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Giant Flower Carpet on the Grand Place in Brussels Pays Tribute to Turkish Immigrants". International Business Times UK. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand Place. |