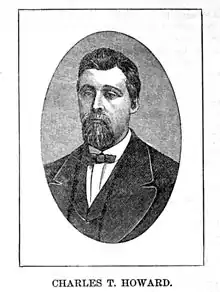

Charles T. Howard

Charles Turner Howard (1832–1885) was an American businessman notable for organizing the Louisiana State Lottery Company in 1869.[2] This corporation bribed Louisiana lawmakers to enable it to stay in business, and the firm amassed a considerable fortune over the years while Howard led a controversial life. He died at age 53 after a fall off of a carriage in Dobbs Ferry, New York, but his family continued his efforts at philanthropy and charitable giving.

Charles Turner Howard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 4, 1832 |

| Died | May 31, 1885 (aged 53) |

| Nationality | American |

| Years active | 1868–1885 |

| Known for | Louisiana Lottery Company |

| Spouse(s) | Florestile Boullemet Howard[1] |

| Children | Frank Turner Howard, Harry Turner Howard, William Turner Howard, Annie Turner Howard[1] |

Howard was born in Baltimore and attended college in this city. He moved south, and worked as a newsdealer and then later as a lottery and policy dealer. When the Civil War broke out, Howard's business dealings were described as "obscure" according to a report in The New York Times.[2] At a later point in his life, he claimed to have been a soldier for the confederate side for Tennessee, but this was subsequently disproven.[2] In 1866, he was hired by the Kentucky lottery firm of C. H. Murray & Company to apply for a lottery charter in Louisiana from the state legislature. This effort failed, but after two years, a second attempt succeeded, partially as a result of bribery of key lawmakers in Louisiana.[2] Howard was given $50,000 to apply for a charter and when the legislative grant came through, he refused to turn the charter over to his employers. A member of the firm of C. H. Murray & Co. named Marcus Cicero Stanley filed suit against Howard for being refused his "just share of the profits".[3] The suit alleged that Howard had bribed a "large number of legislators" as well as an ex-Governor of Louisiana.[3] But the lawsuit was dropped because it was decided that, given the nature of the gambling business, that the parties had no legal standing to enforce the contract.[2]

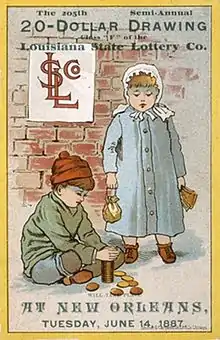

The Louisiana Lottery Company gave Howard and his partners profits of 50%, and business began in January 1869. Howard used monies from the lottery to help win favor with the state legislature.[2]

In November, 1869, Louisiana Hose, one of 24 volunteer fire companies in New Orleans, having received a handsome new Amoskeag steamer, chose as the name for it that of “Annie Howard.” the daughter of Charles T. Howard, one of their former members and one of the best friends the Fire Department ever had.

On the evening of November 26, 1869, having indicated to Mr. Howard their intention of naming their new machine in honor of his little daughter, the members responded to that gentleman's invitation to come to his house-then 699 Magazine St.- in order that he might add some features to the ceremony of the christening that he thought the members would regard as appropriate and agreeable.

Consequently, the way from the engine house on First Street was illuminated with the glare of torches and enlivened with the strains of martial music, as the company with their new engine proceeded to the Howard residence. Upon arrival, the christening was at once proceeded with, Joseph P Horner, an exempt member of Louisiana Hose, making the address to the host of the evening. At the conclusion of his remarks he broke a bottle of wine over the engine and named her “Annie Howard”. Thereupon the youthful and charming original stepped forward to the edge of the veranda and presented to the company a handsome ribbon inscribed with the chosen name in letters of gold and green, indicative of hope and prosperity, and a wreath of flowers to crown the gift. With that the doors of the house were thrown open to the guests.

A sequel to the story occurred five years later, in 1874. This was the christening of another new engine for Louisiana Hose company, the latest model Amoskeag which replaced the earlier unit. Five years of arduous service with the original engine had endeared the name and so it was resolved that the new engine would be christened with the same name.

The evening commenced with a procession composed of members of the company as well as four representatives from each of the twenty four companies in the city, and many invited guests. It began on Carondelet St., in front of the engine house. First in the procession was a powerful calcium light, followed by a thirty six member band. Following the band were the guests and behind all were the 'Louisiana” boys with the new engine pulled by a team of four white caparisoned horses. Long rows of lights were borne on each side and in front of the line while the engine itself was illuminated by means of a girdle of gas jets which extended around the perimeter of the engine.

Having marched through the principal streets of the Second district, the line of march then headed for the residence of Mr. Howard, then at 132 Prytania Street, arriving between nine and ten o'clock. Sky rockets and other fire works announced the procession. As the line halted in front of the residence, the band played the air, 'Gentle Annie” and then the gates were thrown open and the procession filled into the beautifully illuminated grounds. Within the house was gathered a large company of ladies and gentlemen. The whole number of persons directly participating in the christening was scarcely less than one thousand.

After the christening, guests proceeded to a pavilion on the grounds capable of entertaining at table nearly 600 people at five long tables. It was indeed a grand banquet, worthy of the occasion, worthy of the known liberality of Mr. Howard and was intensely enjoyed by all. After the banquet, sparkling wine was introduced and Mr. R.H. Benners, the Foreman of Louisiana Hose, gave the first toast, pledging the health and happiness of Miss Annie Howard. The feasting and toasting continued until a late hour, when the company retired, satisfied with them selves, satisfied with their generous host, and fully persuaded that a private entertainment on so large a scale was never before been given in the Crescent City. Source: History of the Fire Department of New Orleans cc1895, pages 398, 401,402

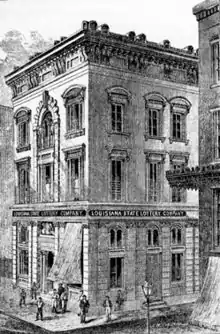

In less than a year the company was enabled to put under its control the Legislature and the politics of the entire State. Its paid agents were on the floor of the Legislature not only as lobbyists, but as members of both houses. More than one Governor of the State acknowledged its sway, and the Mayor of the capital city of Baton Rouge was one of its regular agents for the sale of tickets.

— The New York Times[2]

Howard and his partners were adept at using money and influence to keep the lottery going and profitable. At one point, a state Constitutional Convention was about to be passed which would have outlawed the lottery, but "false pretenses, bribery and coercion" were used to ensure that any new constitution did not exclude the lottery.[2] At one point, a Louisiana judge made some "extraneous remarks" which had "no legal value" which said that the new Louisiana Constitution had "legalized" the Louisiana Lottery, and Howard made sure not to appeal this decision. During its heyday, the firm divided about $2 million annually among stockholders, including Howard, as well as pay for the numerous bribes for public officials.[2]

Howard built a beautiful house on St. Charles Street in New Orleans with a garden described as the "finest in the city."[2] He had a second home in Dobbs Ferry, a suburb of New York City. He acquired a reputation for giving generously to the city's charitable institutions.[2] While he was a social climber, he did not respond kindly to snubs, and he "got even" with groups and organizations which had excluded him, such as the Metairie Jockey Club and the La Variétés Club, by waiting patiently, buying up the properties at propitious times, and casting out the snubbers.

A noted instance of the manner in which he got even with those who refused to associate with him was afforded in his treatment of the Metairie Jockey Club. He sought an entrance in the company of this association, whose race course was the most noted in the South. The club, however, refused to admit him, and he swore that he would buy out their course and turn it into a graveyard. he bided his time, and when the opportunity came he did according to his oath. The beautiful Metairie Cemetery took the place of the Metairie race course, and a new course was established by Howard in its stead.

— Report in The New York Times, 1885[2]

Howard was involved in controversy on several occasions. When a serious fever struck New Orleans in 1878, one report suggested that Howard has not contributed any monies to a relief effort.[4] In 1879, he was arrested in New York City for starting lottery agencies to sell shares or tickets of the Louisiana State Lottery.[5] A detective charged that he had been selling lottery tickets which had been against the laws of New York State at the time.[5] There was no record of Howard having spent any time in jail, but he was reported to own an interest in a sugar plantation, own a "stud of horses", have financial interests in two New Orleans newspapers, and at one point aspired to the office of Governor of Louisiana.[5]

Howard died in a carriage accident in 1885 when he was thrown from the vehicle and severely injured.[2]

The name of Charles T. Howard will be remembered in the city of New Orleans as that of a good friend to so many deserving charities, individuals and enterprises that a list of them would fill a volume: for he was one of the most generous of men and the large fortune he amassed was ever at the disposal of the needy, Cut off by a sudden and accidental death in the prime of life, he left not only troops of friends, but many dependents to mourn his loss.

Mr. Howard was borne in 1832. He attended college in the East, but came to the South in early manhood, embarking in business first in Mobile Alabama and then removing to New Orleans. Hardly had he begun life here than war broke out, and, true to the land of his adoption he entered the military service of the South, holding a commission in the Crescent Regiment. Upon his return to New Orleans at the end of the war he associated himself with others in the establishment of the Louisiana State Lottery Company, which from being at first a local soon became a national enterprise. He engaged in many enterprises of an industrial nature, and the considerable fortune that resulted from them he employed in doing good, and one of the most touching incidents at his funeral was the genuine mourning of those good sisters whom he had made almoners of his boundless charities. He took an active part in all that interested the leading spirits of the city, and was as public spirited in civic affairs and generous socially as he was benevolent in his dealings with the poor and needy. Vast public improvements were funded by him and in some instances were undertaken by him alone. He came to be a very conspicuous figure in New Orleans life in almost every line of activity. His death came at a time when his identification with prominent interests was fully established, and his loss was severely felt. It occurred on May 31, 1885, as a result of a fall from his horse while riding, at his Northern Home in Ingleside, near Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.

His funeral, from his residence on St. Charles Ave. was attended by the leading citizens of New Orleans, by delegations from the John A. Mower Post, of the Army of Tennessee, Louisiana Hose Company, and many commercial institutions, and no less than four orphan asylums sent several hundred of their little charges to lay their humble offerings on the bier of one of whom one of the Sisters said, through her tears, “he was so good to the orphans.” The pall-bearers were Gen. G.T. Beauregard, Judge G.H. Braughn, L.C. Jurey, Judge Walter Rogers, Albert Baldwin, J.P. Horner,

E. Belknap, J. O. Nixon and R.H. Benners. Mr. Howard was identified with the Fire Department by a long membership in Louisiana Hose Company, and at the time of his death the engine house of his company was handsomely draped in his memory.

Source: History of the Fire Department of New Orleans cc 1895 Page 551

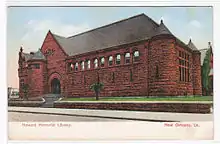

Howard's son, Frank T. Howard, continued in the lottery business and amassed fortunes, according to one account, with revenues of $4,000,000 a month reported, with about 60% of that being paid out in the form of prizes.[6] Howard's daughter, Annie Howard, along with her brothers helped to build the Howard Memorial Library[7] as well as the Louisiana Historical Annex, which has a collection of Confederate archives, including the private and state papers of southern president Jefferson Davis.[8]

References

- "Charles T. Howard's Will". The New York Times. June 16, 1885. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- "A Noted Lottery Man Dead – Career of Charles T. Howard, of the Louisiana Company". The New York Times. June 1, 1885. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

Charles T. Howard, of New-Orleans, the well-known chief of the Louisiana Lottery Company, died at Ingleside, Dobbs Ferry, in this State, yesterday. While out driving on Wednesday he was thrown from his carriage

- "The Louisiana Lottery. Marcus Cicero Stanley's Suit Against the Company". The New York Times. July 24, 1880. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- "Desolation in the South – Fearful Spread of the River at New-Orleans – Its Progress Since Sunday Estimated at 1,000 Cases a Day – Peculiar Features of the Disease and Its treatment – Partial Fulfillment of the Prophecy of a Voudoo Sorcerer". The New York Times. September 5, 1878. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- "Violating the Lottery Law – Charles T. Howard, of New-Orleans, Arrested in This City". The New York Times. December 27, 1879. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

The first charge specifies that Howard has started agencies for the sale of $522,500 worth of shares of tickets of the Louisiana State Lottery....

- "$6,000,000 a year lottery profits". The New York Times. April 15, 1907. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

In its halcyon days the Louisiana Lottery Company's possible receipts were $4,000,000 a month, with prizes running around 60 per cent thereof...

- "A Library for New-Orleans". The New York Times. January 30, 1887. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- "Gerth Took the Diamonds". The New York Times. August 24, 1893. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

(see accompanying story)