Chine (boating)

A chine in boat design is a sharp change in angle in the cross section of a hull. The chine typically arises from the use of sheet materials (such as sheet metal or marine ply) as the mode of construction.

Rationale of chines

Using sheet materials in boat construction is cheap and simple, but whereas these sheet materials are flexible longitudinally, they tend to be rigid vertically. Examples of steel vessels with hard chines include narrowboats and widebeams; examples of plywood vessels with hard chines include sailing dinghies such as the single-chined Graduate and the double-chined Enterprise. Although a hull made from sheet materials might be unattractively "slab-sided", most chined hulls are designed to be pleasing to the eye and hydrodynamically efficient.

Hulls without chines (such as clinker-built or carvel-built vessels) usually have a gradually curving cross section.

A hard chine is an angle with little rounding, where a soft chine would be more rounded, but still involve the meeting of distinct planes. Chine log construction is a method of building hard chine boat hulls. Hard chines are common in plywood hulls, while soft chines are often found on fiberglass hulls.

Traditional planked hulls in most cultures are built by placing wooden planks oriented parallel to the waterflow and attached to bent wooden frames. This also produced a rounded hull, generally with a sharp bottom edge to form the keel. Planked boats were built in this manner for most of history.

The first hulls to start incorporating hard chines were probably shallow draft cargo carrying vessels used on rivers and in canals.[1]

Once sufficiently powerful marine motors had been developed to allow powerboats to plane, it was found that the flat underside of a chined boat provided maximum hydrodynamic lift and speed.[2]

Boats using chines

The scow in particular, in the form of the scow schooner, was the first significant example of a hard chine sailing vessel. While sailing scows had a poor safety reputation, that was due more to their typical cheap construction and tendency to founder in storms. As long as it sailed in the protected inland and coastal waters it was designed to operate in, however, the sailing scow was an efficient and cost effective solution to transporting goods from inland sources to the coast. A good example of this is the gundalow.[3]

Working in the same inland waters as the sailing scows was the later river steamboat. River steamboats were often built using the same hard chined construction methods of the sailing scows, with a flat bottom, hard chine, and nearly vertical sides.[4]

The punt is one of the simplest hard chine small boats. Consisting usually of a single plank for each side, with a square bow and stern, the punt was in essence a tiny scow.

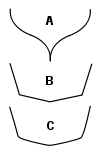

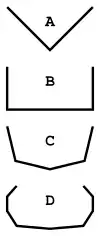

Various types of chine hulls

The simplest type of chine construction is the single chine "V" shape, with two flat panels joined at the keel (A). This type of hull is among the simplest to build, but they lack stability on a narrow "V" and may lack freeboard on a wide "V". Single chine hulls are generally only seen on multihull sailboats, which often use two deep "V" shaped hulls connected by akas to provide mutual stability.

The two chine hull (B), with a flat bottom and nearly vertical sides, was the first hard chine design to achieve widespread use. This design provides far more stability than the single chine hull, with minimum draft and a large cargo capacity. These characteristics make the two chine hull popular for punts, barges, and scows.

The three chine hull (C) is probably the most common hard chine hull. Having a shallow "V" in the bottom and near-vertical panels above that, it approximates the shape of traditional rounded hull boats fairly well. This hull is common, even in fiberglass designs where employing chines offers no advantage in construction.

Designs with higher numbers of chines (D), often just called multichine hulls, are also common. By increasing the number of chines, the hull can very closely approximate a round bottomed hull. Kayaks, in particular, are often composed of many chines, required for the complex shapes needed to provide good performance under various conditions.

It is possible to refer to the different hulls by the numbers of the flat panels that make up the boat. Thus A is a two-panel boat, B is a three-panel boat, C is a four-panel boat and D is an eight-panel boat.

Plank hulls

Plank hulls use wooden supports placed along the chines called chine logs to provide strength where the chines joined. Beams are then attached to the chine log to support planks running parallel to the chine, while cross-planked sections such as a typical scow bottom may be attached directly to the chine log. This method of construction originated with the sailing scow[5] and continues to be used today, primarily in home built boats.

Chine log construction works best for hulls where the sides join a flat bottom at a right angle, but it can be used for other angles as well with an appropriately angled chine log. Builders of small boats such as punts, where the plank thickness is large compared to the size of the hull, can dispense with the chine log and nail intersecting planks directly into one another.

Plywood hulls

A chined hull built out of plywood will often be designed to keep most of the lengthwise joints between the plywood sheets at the chines, thus making the building process easier. While chine logs (often just called chines) can be used for plywood boats,[6] another common technique replaces the chine logs with a fiberglass and epoxy fillet joint that provides both connection and stiffness to the joint; this method is most commonly called stitch and glue construction.

Padded v-hulls

A padded v-hull is a hull shape found on both pure race boats and standard recreational craft. A variation of the more common v-hull, which has a v-section throughout the length of the vessel, a padded v-hull has a v-section at the bows and the forward part of the keel which then segues into a flat area typically 0.15 metres (5.9 in) to 0.25 metres (9.8 in) wide. This flat area at the rear is the "pad", and is said to provide hydrodynamic lift more efficiently due to very low deadrise planing surface (compared to the vee hull lifting surfaces). This highly efficient lift helps to unwet the less efficient vee sections hull, thereby dramatically reducing drag (force). As the boat's speed increases, hydrodynamic pressure beneath the pad causes the hull to ride higher in the water, so that eventually the boat will be riding solely upon the pad area.

At low speeds these hulls ride and handle similarly to a comparable v-hull; but at high speeds the padded hull can both out-accelerate and have a higher top speed than a similarly powered v-hull. Piloting a padded v-hull requires considerable skill, since at high speed the hull is riding upon a small pad. The driver must make slight, accurate steering inputs to maintain level progress, as otherwise padded v-hulls tend to chine-walk.[7] As speeds increase, chine-walk becomes more pronounced and may lead to loss of control unless the driver is able to compensate for it.[8]

See also

External links

References

- Frederick M. Hocker; Cheryl A. Ward (2004). The Philosophy of Shipbuilding: Conceptual Approaches to the Study of Wooden Ships. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-1-58544-313-0.

- Eric Sorensen (22 November 2007). Sorensen's Guide to Powerboats, 2/E. McGraw Hill Professional. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-0-07-159474-5.

- Abel B. Berry (1887). The Last Penacook: A Tale of Provincial Times. D. Lothrop. pp. 31–.

- Samson specs page Archived 2006-08-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Wisconsin's Maritime Trails - Notes From the Field Journal Entry Archived 2006-05-13 at the Wayback Machine

- PDRacer Sailboat

- Note: Chine-walk is when the boat rocks side to side on the rear portion of the hull.

- "Padded V-Hull". boatsdepot.org. Retrieved 2 December 2019.