Chromosomal deletion syndrome

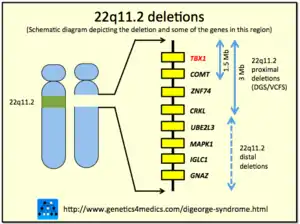

Chromosomal deletion syndromes result from deletion of parts of chromosomes. Depending on the location, size, and whom the deletion is inherited from, there are a few known different variations of chromosome deletions. Chromosomal deletion syndromes typically involve larger deletions that are visible using karyotyping techniques. Smaller deletions result in Microdeletion syndrome, which are detected using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

| Chromosomal deletion syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| An example of chromosomal deletions |

Examples of chromosomal deletion syndromes include 5p-Deletion (cri du chat syndrome), 4p-Deletion (Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome), Prader–Willi syndrome, and Angelman syndrome.[1]

5p-Deletion

The chromosomal basis of Cri du chat syndrome consists of a deletion of the most terminal portion of the short arm of chromosome 5. 5p deletions, whether terminal or interstitial, occur at different breakpoints; the chromosomal basis generally consists of a deletion on the short arm of chromosome 5. The variability seen among individuals may be attributed to the differences in their genotypes. With an incidence of 1 in 15,000 to 1 in 50,000 live births, it is suggested to be one of the most common contiguous gene deletion disorders. 5p deletions are most common de novo occurrences, which are paternal in origin in 80–90% of cases, possibly arising from chromosome breakage during gamete formation in males

Some examples of the possible dysmorphic features include: downslanting palpebral fissures, broad nasal bridge, microcephaly, low-set ears, preauricular tags, round faces, short neck, micrognathia, and dental malocclusionhypertelorism, epicanthal folds, downturned corners of the mouth. There is no specific correlation found between size of deletion and severity of clinical features because the results vary so widely.[2]

4p-Deletion

The chromosomal basis of Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome (WHS) consists of a deletion of the most terminal portion of the short arm of chromosome 4. The deleted segment of reported individuals represent about one half of the p arm, occurring distal to the bands 4p15.1-p15.2. The proximal boundary of the WHSCR was defined by a 1.9 megabase terminal deletion of 4p16.3. This allele includes the proposed candidate genes LEMT1 and WHSC1. This was identified by two individuals that exhibited all 4 components of the core WHS phenotype, which allowed scientists to trace the loci of the deleted genes. Many reports are particularly striking in the appearance of the craniofacial structure (prominent forehead, hypertelorism, the wide bridge of the nose continuing to the forehead) which has led to the descriptive term “Greek warrior helmet appearance.

There is wide evidence that the WHS core phenotype (growth delay, intellectual disability, seizures, and distinctive craniofacial features) is due to haploinsufficiency of several closely linked genes as opposed to a single gene. Related genes that impact variation include:

- WHSC1 spans a 90-kb genomic region, two-thirds of which maps in the telomeric end of the WHCR; WHSC1 may play a significant role in normal development. Its deletion likely contributes to the WHS phenotype. However, variation in severity and phenotype of WHS suggests possible roles for genes that lie proximally and distally to the WHSCR.

- WHSC2 (also known as NELF-A) is involved in multiple aspects of mRNA processing and the cell cycle

- SLBP, a gene encoding Stem Loop Binding Protein, resides telomeric to WHSC2, and plays a crucial role in regulating histone synthesis and availability during S phase

- LETM1 has initially been proposed as a candidate gene for seizures; it functions in ion exchange with potential roles in cell signaling and energy production.

- FGFRL1, encoding a putative fibroblast growth factor decoy receptor, has been implicated in the craniofacial phenotype and potentially other skeletal features, and short stature of WHS

- CPLX1 has lately been suggested as a potential candidate gene for epilepsy in WHS[3]

Prader-Willi vs. Angelman Syndrome

Prader-WIlli (PWS) and Angelman syndrome (AS) are distinct neurogenetic disorders caused by chromosomal deletions, uniparental disomy or loss of the imprinted gene expression in the 15q11-q13 region. Whether an individual exhibits PWS or AS depends on if there is a lack of the paternally expressed gene to contribute to the region.

PWS is frequently found to be the reason for secondary obesity due to early onset hyperphagia - the abnormal increase in appetite for consumption of food. There are known three molecular causes of Prader–Willi syndrome development. One of them consists in micro-deletions of the chromosome region 15q11–q13. 70% of patients present a 5–7-Mb de novo deletion in the proximal region of the paternal chromosome 15. The second frequent genetic abnormality (~ 25–30% of cases) is maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 15. The mechanism is due to maternal meiotic non-disjunction followed by mitotic loss of the paternal chromosome 15 after fertilization. The third cause for PWS is the disruption of the imprinting process on the paternally inherited chromosome 15 (epigenetic phenomena). This disruption is present in approximately 2–5% of affected individuals. Less than 20% of individuals with an imprinting defect are found to have a very small deletion in the PWS imprinting centre region, located at the 5′ end of the SNRPN gene.[4]

AS is a severe debilitating neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by mental retardation, speech impairment, seizures, motor dysfunction, and a high prevalence of autism. The paternal origin of the genetic material that is affected in the syndrome is important because the particular region of chromosome 15 involved is subject to parent-of-origin imprinting, meaning that for a number of genes in this region, only one copy of the gene is expressed while the other is silenced through imprinting. For the genes affected in PWS, it is the maternal copy that is usually imprinted (and thus is silenced), while the mutated paternal copy is not functional.[5]

See also

References

- "Chromosomal deletion syndromes". Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- Nguyen, Joanne M.; Qualmann, Krista J.; Okashah, Rebecca; Reilly, AmySue; Alexeyev, Mikhail F.; Campbell, Dennis J. (2015-09-01). "5p deletions: Current knowledge and future directions". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C. 169 (3): 224–238. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31444. ISSN 1552-4876. PMC 4736720. PMID 26235846.

- Battaglia, Agatino; Carey, John C.; South, Sarah T. (2015-09-01). "Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome: A review and update". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C. 169 (3): 216–223. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31449. ISSN 1552-4876. PMID 26239400.

- Botezatu, Anca; Puiu, Maria; Cucu, Natalia; Diaconu, Carmen C.; Badiu, C.; Arsene, C.; Iancu, Iulia V.; Plesa, Adriana; Anton, Gabriela (2015-09-01). "Comparative molecular approaches in Prader-Willi syndrome diagnosis". Gene. 575 (2 Pt 1): 353–8. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2015.08.058. ISSN 1879-0038. PMID 26335514.

- Cassidy, Suzanne B.; Schwartz, Stuart; Miller, Jennifer L.; Driscoll, Daniel J. (2012-01-01). "Prader-Willi syndrome". Genetics in Medicine. 14 (1): 10–26. doi:10.1038/gim.0b013e31822bead0. ISSN 1098-3600. PMID 22237428.