Chronicles of Barsetshire

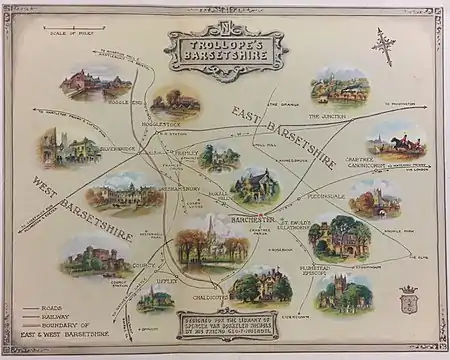

The Chronicles of Barsetshire is a series of six novels by English author Anthony Trollope, published between 1855 and 1867. They are set in the fictional English county of Barsetshire and its cathedral town of Barchester.[1] The novels concern the dealings of the clergy and the gentry, and the political, amatory, and social manoeuvrings that go on among them.[2]

| The Warden (1855) Barchester Towers (1857) Doctor Thorne (1858) Framley Parsonage (1860) The Small House at Allington (1862) The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867) | |

| Author | Anthony Trollope |

|---|---|

| Country | England, United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Victorian, Literary fiction |

| Publisher | Longmans Chapman and Hall Smith, Elder and Co. |

| Published | 1 January 1855 – 6 July 1867 (initial publication) |

| Media type | Print (Serial and Hardback) Audiobook E-Book |

| No. of books | 6 |

A series was not planned when Trollope began writing The Warden.[3] Rather, after creating Barsetshire, he found himself returning to it as the setting for his following works.[3] It wasn't until 1878, 11 years after The Last Chronicle of Barset, that these six novels were collectively published as the Chronicles of Barset.

By many, this series is regarded as Trollope's finest work.[4] Both modern and contemporary critics have praised the realism of the Barsetshire county and the intricacies of its characters. However, Trollope also received criticism, particularly for his plot development and the use of an intrusive narrative voice.

The series has been adapted for television in The Barchester Chronicles (1982) and Doctor Thorne (2016) and as dramatised radio programmes produced by BBC Radio 4.[5] Author Angella Thirkell continued writing novels set in Barsetshire throughout the twentieth century.[6]

Plot summary

The Warden

Mr Harding, Warden of Hiram’s Hospital, is accused of dishonestly allocating hospital finances. However the accuser, John Bold, is actually in love with Mr Harding’s daughter, Eleanor. Nevertheless, John takes the matter to the press, subjecting Mr Harding to public incrimination. Mr Harding’s is supported by his son-in-law, Archdeacon Grantly, who insists he maintain his innocence. Finally, following an ultimatum from Eleanor, John drops the case and apologises. Eleanor and John get married and Mr Harding resigns as Warden of Hiram to become Rector of St. Cuthberts. [7][8][9]

Barchester Towers

Following the death of Bishop Grantly, Dr Proudie is appointed as the new Bishop, defeating rival candidate and son of the former Bishop, Archdeacon Grantly. Dr Proudie (now Bishop Proudie) is supported by his imperious wife, Mrs Proudie and the Chaplain, Mr Slope, all of whom want to steer the church away from traditional values. To fill the position of Warden at Hiram's Hospital, Mrs Proudie insists Mr Slope backs Mr Quiverful for the role. However, Mr Slope is infatuated with widow Eleanor Bold, and instead, secretly supports the reappointment of her father Mr Harding, alongside the Archdeacon and Mr Arabin. Mr Slope eventually proposes to Eleanor, and in doing so, exposes his dealings with both sides. In the end, he is ostracised by the community, while Mr Arabin marries Eleanor and Mr Quiverful is appointed Warden of Hiram.[9][10][11]

Doctor Thorne

After the Greshamsbury estate suffers a significant loss in value, Frank Gresham, heir to the Greshamsbury estate, is being pressed by his family to marry a woman of wealth, such as Mrs Dunstable. However, Frank is in love with Mary Thorne, niece of the Gresham’s family physician, Doctor Thorne. While Mary appears to have no fortune, she is actually the illegitimate niece of the millionaire Sir Roger Scatcherd, a fact known only to Doctor Thorne. Following the death of Roger and his son Louis, Mary, being the eldest niece, receives Roger’s inheritance. Despite having already consented to their marriage, Frank’s family are far more welcoming of Mary after hearing she now has the wealth to restore the estate's fortune.[9][12][13]

Framley Parsonage

In an attempt to make connections with high society, young vicar Mark Robarts foolishly guarantees a loan to the corrupt MP, Nate Sowerby. With Mr Sowerby not repaying the loan, Mark’s friend Lord Lufton eventually steps in and saves his friend from financial disaster. All the while, Mark’s sister Lucy moves to Framley and falls in love with Lord Lufton. However, Lucy rejects Lord Lufton’s proposal, knowing that his mother, Lady Lufton, refuses to accept women of her status. Lady Lufton is adamant her son marry Griselda Grantly, daughter of the Archdeacon. However in the end, Lady Lufton abandons her pretentious desires, and asks Lucy to accept her son’s proposal, particularly after witnessing Lucy selflessly care for Mrs Crawley. Meanwhile, Mrs Proudie reappears and reignites a feud with the Archdeacon and his wife, Mrs Grantly. Another subplot features the marriage of Doctor Thorne and the wealthy Mrs Dunstable, who was initially the choice of Frank Gresham’s family.[9][14][15]

The Small House at Allington

Sisters Bell and Lily Dale live with their widowed mother in the Small House of Allington. The squire, Christopher Dale, wants Bell to marry his nephew Bernard, who is heir to the estate. Bernard introduces Lily Dale to Adolphus Crosbie, who later proposes to her. However upon learning Lily Dale is not entitled to any significant inheritance, Crosbie also proposes to Lady Alexandria of the prominent de Courcy family, leaving Lily Dale heartbroken. Upon hearing this, Johnny Eames, lifelong admirer of Lily Dale, beats up Crosbie in an act of which promotes him to local hero. Yet despite his devotion, Lily Dale, still emotionally devastated, rejects his proposal and chooses instead to live with her mother. In the end, Bell marries a local doctor, while Crosbie and Lady Alexandria abandon their engagement.[9][16][17]

The Last Chronicle of Barset

The main storyline follows Rev. Josiah Crawley, introduced in Framley Parsonage, who is ostracised by the community after being wrongly accused of stealing money. Meanwhile, Major Grantly, son of the Archdeacon, falls for daughter of the disgraced Reverend, Grace Crawely. The Archdeacon, initially objecting to the marriage, eventually consents after Mr Crawley’s innocence is confirmed. John Eames continues an unsuccessful pursuit for Lily Dale, while the beloved Warden, Mr Harding, dies of old age. Mrs Proudie also reappears, and demands her husband, Bishop Proudie, ban Mr Crawley from holding services. However, being a proud man, Mr Crawely refuses to comply, before Mrs Proudie dies of a heart attack.[9][18][19]

Conception and publication

.jpg.webp)

While working at the General Post Office, Trollope travelled through the English countryside, witnessing the conventions of rural life and the politics surrounding the church and the manor house.[20] On one particular trip to the cathedral town of Salisbury in 1852, Trollope developed his ideas for The Warden, of which centred around the clergy.[21] In doing so, the county of Barsetshire was born.[22][23] However, Trollope did not begin writing The Warden until July, 1853 - a year after his trip to Salisbury.[21] Upon completion, he sent the manuscript to Longman for publishing, with the first copies released in 1855.[20] While it was not a huge success, Trollope felt he had received more recognition than for any of his previous works.[21]

While The Warden was intended as a one-off,[24] Trollope returned to Barsetshire for the sequel, Barchester Towers.[24] It was published in 1857, again by Longmans, finding a similar level of success to its predecessor.[23]

However, Trollope’s greatest literary success, based on copies sold, came in the third Barsetshire instalment, Doctor Thorne.[21] It was published by Chapman and Hall in 1858.[25] Trollope credits his brother Tom for developing the storyline.[21]

Following this success, The Cornhill magazine approached Trollope requesting he write a novel to be released in serial parts.[26] Thus, Trollope began what is now Framley Parsonage. In his autobiography, he explains that by "placing Framley Parsonage near Barchester, I was able to fall back upon my old friends" [21] hence forming what is now the fourth Chronicle of Barsetshire. The novel was released to The Cornhill in 16 monthly instalments, from January 1860 - April 1861, and later published as a three volume work by Smith, Elder and Co..[27]

Now at the height of his popularity,[28] Trollope wrote the fifth novel in the series; The Small House at Allington.[26] It too was published in serial parts between September 1862 and April 1864 in The Cornhill, and also published as a 2 volume novel by Smith, Elder and Co. in 1864.[26] Regarding his inspiration, some suggest the character of Johnny Eames was inspired by Trollope’s reflection of his younger self.[29] Finally, came the Last Chronicle of Barset, of which Trollope claimed was "the best novel I have written".[21] He took inspiration from his father when creating protagonist Josiah Crawley, while reflecting his mother in the character of Mrs Crawley.[30] Again, it was released serially between 1866 and 1867 and later published as a 2 volume work in 1867 by Smith, Elder and Co.[30]

There is little to suggest that Anthony Trollope ever planned on writing these six novels collectively as the Chronicles of Barsetshire.[24][4] Rather, after developing the county of Barsetshire in The Warden, Trollope found himself frequently returning, often in response to the request of publishers. In doing so, prominent characters like Mrs Proudie and the Archdeacon could be reintroduced. It wasn’t until he wrote Framley Parsonage that Trollope began to envision these works culminating to a series.[4] In his autobiography, he notes that after releasing The Last Chronicle of Barset, he wished for a "combined republication of those tales which are occupied within the fictitious county of Barsetshire".[21] However, due to copyright issues, the six works were not formally republished as the Chronicles of Barset until 1878, 11 years after the Last Chronicle. It was published by Chapman and Hall, of whom also published Doctor Thorne.[24]

Reception

As a series

The Chronicles of Barsetshire are widely regarded as Anthony Trollope’s most famous literary works.[4][31] In 1867, following the release of The Last Chronicle of Barset, a writer for The Examiner called these novels "the best set of sequels in our literature".[32] Even today, these works remain his most popular. Modern critic Arthur Pollard writes; "Trollope is and will remain best known for his Barsetshire series",[4] while P. D. Edwards offers a similar insight; "During his own lifetime, and for long afterwards, his reputation rested chiefly on the Barsetshire novels".[31]

Despite a series not initially being intended,[24] few have argued against the importance of appreciating each novel as part of the Chronicles of Barsetshire. As R. C. Terry writes, "the ironies embedded in the novel achieve their full effect only when one considers the entire Barsetshire series".[28] Mary Poovey suggests that even before they were formally published as a series, reviewers understood their collective value. As The Examiner (1867) wrote; "the public should have these Barsetshire novels extant, not only as detached works, but duly bound, lettered, and bought as a connected series".[24]

Discussion has also surrounded the extent to which Trollope’s literary prowess is displayed throughout the Chronicles of Barsetshire. R.C. Terry argues that the series does "not reveal all of Trollope’s skills" [28] while A. O. J. Cockshut similarly believes it is "simple in conception" and "not fully characteristic of his genius".[33] However, in his response to Cockshut, Miguel Ángel Pérez Pérez argues that "Trollope disguises many of his own opinions"[24] throughout the series, and therefore they "are not so simple in conception, since they allow for different readings".[24]

Praise

Trollope was praised for the characters he developed throughout the series. The London Review (1867) stated "we have thoroughly accepted the reality of their existence",[32] while The Athnenaeum (1867) wrote, "if the reader does not believe in Barsetshire and all who live therein […] the fault is not in Mr Trollope, but in himself".[32] Most reviewers, like The Examiner (1867), agreed that reintroducing characters into the later instalment was Trollope "realiz[ing these characters] more and more completely".[24] Mary Poovey similarly believes that such repetition meant the characters "seemed to live outside the pages of the novels"[24]. However, in contrast, the Saturday Review (1861) wrote that Trollope’s practice of "borrowing from himself" was "at best a lazy and seductive artifice".[32]

Trollope was also praised for the creation of Barsetshire,[34] with critics like Arthur Pollard writing “He has created a recognisable world". Similarly, Nathaniel Hawthorne claimed it was "as if some giant had hewn a great lump out of the earth and put it under a glass case, with all its inhabitants going about their daily business".[35] Contemporary reviewers like The Examiner (1858) also praised the realism of his fictitious world; "[Trollope] invites us, not to Barchester, but into Barsetshire".[32] However, while inspired by real English counties, Barsetshire was, as P. D. Edwards writes, "explicitly his own creature" [36]. Andrew Wright explains this union of the real and imaginary as being "conjured up out of an imagination that is at once fantastic and domestic".[22] Moreover, Arthur Pollard argues that setting these novels within "the clerical community" was "a brilliant choice" as it was "the central concern in the eyes of the nation".[4]

The Chronicles of Barsetshire were also commended by Trollope’s literary contemporaries. Margaret Oliphant called the series "the most perfect art […] a kind of inspiration",[24] while Virginia Woolf wrote: "We believe in Barchester as we believe in the reality of our own weekly bills".[27] A writer for The Saturday Review (1864) compared Trollope’s work to that of Jane Austen, arguing that in The Small House at Allington, Trollope does "what Miss Austen did, only that he does it in the modern style, with far more detail and far more analysis of character".[32]

Criticism

The series has been subject to criticism regarding its plot development. The Saturday Review (1861) wrote that "The plot of Framley Parsonage is really extremely poor",[32] going so far as to say "Mr Trollope is not naturally a good constructor of plots".[32] Similarly, critic Walter Allen claimed Trollope has "little skill in plot construction",[37] while Stephen Wall suggested the outcome of The Small House at Allington "is visible early on".[38]

Trollope was also criticised, particularly by contemporary reviewers, for his intrusive narrative voice throughout the series. In her essay, Mary Poovey draws on an example from The Warden, where Trollope offers his own insight into the character of Archdeacon Grantly - "our narrative has required that we should see more of his weakness than his strength".[39] The Saturday Review (1861) refers to this as his "petty trick of passing a judgment on his own fictitious personages",[32] while The Leader (1855) argued that because of such judgement "the 'illusion of the scene' is invariably perilled".[32] Similarly, Henry James referred to Trollope as having a "suicidal satisfaction in reminding the reader that the story he was telling was only, after all, make-believe".[40] However, Andrew Wright notes that at the time, it was not uncommon for authors to incorporate their own voice into their stories, and thus criticism such as that of James took issue not with the "intrusiveness, but arbitrariness" [27] of Trollope’s voice. As these novels started being appreciated as a series however, Mary Poovey notes a shift away from this point of criticism. She suggests this was both "a response to changes in Trollope’s novelistic practice" and "a departure from an earlier critical consensus" regarding the use of a personal, narrative voice.[24]

Adaptations

TV series

In 1982, the BBC released The Barchester Chronicles - a television adaptation of The Warden and Barchester Towers, directed by David Giles.[41] The cast featured Nigel Hawthorne as the Archdeacon, Donald Pleasance as Mr Harding, Geraldine McEwan as Mrs Proudie and Alan Rickman as Mr Slope.[41] The series consisted of 7 episodes, released originally on BBC 2 between 10 November and 22 December 1982.[42] The first 2 episodes were dedicated primarily to The Warden while the remaining 5 covered Barchester Towers.[41] In 1983, it received the BAFTA award for Best Design and was nominated for 7 others, including Best Drama Series.[43][44]

In 2016, Doctor Thorne was adapted for television as a 3 part mini-series.[45] In the UK, it was released on ITV between the 6 - 20 March 2016. It was directed by Nial MacCormick and written by Julian Fellows, of whom also created Downton Abbey.[46]

Radio

In 1993, The Small House at Allington was released as a dramatised radio programme on BBC Radio 4.[47] It was created by Martin Wade and directed by Cherry Cookson.[47] Each character was played by a voice actor, with the story being accompanied by music and sound effects.[48] Following its success, the other five novels were also adapted to this form and released between December 1995 and March 1998 as The Chronicles of Barset.[47]

BBC Radio 4 released another radio adaptation titled The Barchester Chronicles in 2014.[49] This programme was created by Michael Symmons Roberts, and also covered all six Barsetshire novels.[50]

Inspired works

Between 1933 - 1961, author Angela Thirkell published 29 novels set in the county of Barsetshire.[6] While Thirkell introduced her own characters, she also incorporates members of Trollope's Barsetshire families, including the Crawelys, Luftons, Grantlys and Greshams.[51] A writer for The New York Times (2008) suggested that "Unlike Trollope, Thirkell is uninterested in money and politics" but is instead, "interested in love".[52] Author M. R. James also used Barchester for the setting of his 1910 novel, The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral [53]

References

- "Barsetshire Novels, The". Trollope Society. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- Daiches, David, ed. (1971). The Penguin Companion to Literature I. p. 527.

- Poovey, Mary (23 December 2010), "Trollope's Barsetshire Series", The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope, Cambridge University Press, pp. 31–43, doi:10.1017/ccol9780521886369.004, ISBN 978-0-521-88636-9, retrieved 26 September 2020

- Pollard, Arthur (2016) [1978]. Anthony Trollope. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-21198-3. OCLC 954490289.

- "TV and radio". Trollope Society. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- Knowles, Elisabeth (2006). The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (Barsetshire). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191727047.

- Trollope, Anthony (2014) [1855]. Shrimpton, Nicholas (ed.). The Warden. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199665440.

- "Warden, The". Trollope Society. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- Birch, Dinah (2009). The Oxford Companion to English Literature (7 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191735066.

- Trollope, Anthony (2014) [1857]. Bowen, John (ed.). Barchester Towers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199665860.

- "Barchester Towers". Trollope Society. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- Trollope, Anthony (2014) [1858]. Dentith, Simon (ed.). Doctor Thorne. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199662784.

- "Doctor Thorne". Trollope Society. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- "Framley Parsonage". Trollope Society. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- Trollope, Anthony (2014) [1860]. Mullin, Katherine; O'Gorman, Francis (eds.). Framely Parsonage. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199663156.

- "Small House at Allington, The". Trollope Society. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- Trollope, Anthony (2014) [1862]. Birch, Dinah (ed.). The Small House at Allington. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199662777.

- Trollope, Anthony (2014) [1867]. Small, Helen (ed.). The Last Chronicle of Barset. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199675999.

- "Last Chronicle Of Barset, The". Trollope Society. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- "Early career". Trollope Society. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- Trollope, Anthony (2009). An Autobiography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781107280106. ISBN 978-1-107-28010-6.

- Wright, Andrew (1983). Anthony Trollope: Dream and Art. London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 978-1-349-06626-1.

- "An introduction to Barchester Towers". The British Library. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Poovey, Mary (23 December 2010), "Trollope's Barsetshire Series", The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope, Cambridge University Press, pp. 31–43, doi:10.1017/ccol9780521886369.004, ISBN 978-0-521-88636-9, retrieved 26 September 2020

- "Doctor Thorne". Trollope Society. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Turner, Mark W. (23 December 2010), "Trollope's Literary Life and Times", The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope, Cambridge University Press, pp. 6–16, doi:10.1017/ccol9780521886369.002, ISBN 978-0-521-88636-9, retrieved 31 October 2020

- Wright, Andrew (1983). Anthony Trollope Dream and Art. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-06626-1. ISBN 978-1-349-06628-5.

- Terry, R. C. (1977). The Artist in Hiding. London: Macmillan Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-03382-9. ISBN 978-1-349-03382-9.

- "Small House at Allington, The". Trollope Society. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "Last Chronicle of Barset, The". Trollope Society. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Edwards, P. D. (2016) [1968]. Anthony Trollope. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-61652-0

- Smalley, Donald (2007). Anthony Trollope: The Critical Heritage. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-13455-2.

- Cockshut, A.O.J. (1955). Anthony Trollope: A Critical Study. London: Collins, in, Pérez Pérez, Miguel Ángel (1999). "The Un-Trollopian Trollope: Some Notes on the Barsetshire Novels". Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingles. 12: 127–142 – via RUA.

- Le Faye, Deirdre, ed. (1996). Jane Austen's Letters. pages xiii and xviii.

- Cowley, M., ed. (1978). The Portable Hawthorne. p. 688.

- Edwards, P. D. (2016) [1968]. Anthony Trollope. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-61652-0. in Wright, Andrew (1983). Anthony Trollope: Dream and Art. London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 978-1-349-06626-1.

- Allen, W. (1991) [1954]. The English Novel, London: Penguin, in Pérez Pérez, Miguel Ángel (1999). "The Un-Trollopian Trollope: Some Notes on the Barsetshire Novels". Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingles. 12: 127–142 – via RUA.

- Wall, S. (1988). Trollope and Character, London: Faber and Faber, ISBN 0571145957, in Pérez Pérez, Miguel Ángel (1999). "The Un-Trollopian Trollope: Some Notes on the Barsetshire Novels". Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingles. 12: 127–142 – via RUA.

- Trollope, A. (1855). The Warden. London: Longmans, in Poovey, Mary (2010-12-23), "Trollope's Barsetshire Series", The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope, Cambridge University Press, pp. 31–43, doi:10.1017/ccol9780521886369.004, ISBN 978-0-521-88636-9, retrieved 2020-09-26

- James, H. (1883). Anthony Trollope. London: Century. pp. 390, in Wright, Andrew (1983). Anthony Trollope Dream and Art. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-06626-1. ISBN 978-1-349-06628-5.

- "The Barchester Chronicles". Trollope Society. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "BFI Screenonline: Barchester Chronicles, The (1982)". www.screenonline.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "Television in 1983 | BAFTA Awards". awards.bafta.org. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- The Barchester Chronicles - IMDb, retrieved 31 October 2020

- "Doctor Thorne". Trollope Society. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Radford, Ceri (6 March 2016). "Doctor Thorne review: Fellowes and Trollope is a happy marriage". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "The Chronicles of Barset (1995-98)". Trollope Society. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "BARCHESTER CHRONICLES by Anthony Trollope Read by a Full Cast | Audiobook Review". AudioFile Magazine. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "The Barchester Chronicles (2014-15)". Trollope Society. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "The Barchester Chronicles". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Bowen, Sara (2017). "Angela Thirkell and "Miss Austen"". The Jane Austen Journal. 39: 112–125 – via Gale Academic Onefile.

- Klinkenborg, Verlyn (2008). "Life, Love and the Pleasures of Literature in Barsetshire". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- Knowles, Elisabeth (2006). The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (Barchester). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191727047.