Chumbi Valley

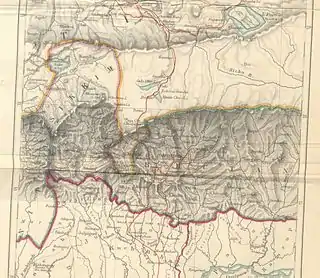

Chumbi Valley (Tibetan: ཆུ་འབི, Wylie: chu vbi ; Chinese: 春丕河谷; pinyin: Chūnpī Hégǔ) is a valley in Yadong County, Tibet Autonomous Region, China. The valley is on the south side of the Himalayan drainage divide, near the Chinese border with Sikkim state of India and with Bhutan.[1] The Chumbi Valley is connected to Sikkim to the southwest via the mountain passes of Nathu La and Jelep La.

| Chumbi Valley | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) | |

| Floor elevation | 3,000 m (9,800 ft) |

| Long-axis direction | north-south |

| Naming | |

| Native name | ཆུ་འབི (Standard Tibetan) |

| Geography | |

| Location | Tibet, China |

| Population centers | Yadong, Pagri, Xarsingma |

| Rivers | Amo Chhu |

The valley is at an altitude of 3,000 m (9,800 ft), and being on the south side of the Himalayas, enjoys a wetter and more temperate climate than most of Tibet. The valley supports some vegetation in the form of the Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests and transitions to the Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows in the north. The plant Pedicularis chumbica (春丕马先蒿) is named after the valley.

Being on one of the primary routes between India and Tibet, the Chumbi Valley has been at the forefront of several military expeditions. The Delhi Sultanate's attempted invasion of Tibet in 1206 reached the Chumbi Valley. The British military expedition of 1904 occupied the Chumbi Valley for about three years after the hostilities[2][3] to secure Tibetan payment of indemnity. Contemporary documents show that the British continued the occupation of Chumbi Valley until February 8, 1908, after having received payment from China. [4]

Strategic significance

Scholar Susan Walcott counts China's Chumbi Valley and India's Siliguri Corridor to its south among "strategic mountain chokepoints critical in global power competition".[5] John Garver has called the Chumbi Valley "the single most strategically important piece of real estate in the entire Himalayan region".[6] The Chumbi Valley intervenes between Sikkim and Bhutan south of the high Himalayas, pointing towards India's Siliguri Corridor like a "dagger". The latter is a narrow 24 kilometer-wide corridor between Nepal and Bangladesh in India's West Bengal state, which connects the central parts of India with the northeastern states including the contested state of Arunachal Pradesh. Often referred to as the "chicken's neck", the Siliguri Corridor represents a strategic vulnerability for India. It is also of key strategic significance to Bhutan, containing the main supply routes into the country.[7]

Historically, both Siliguri and Chumbi Valley were part of a highway of trade between India and Tibet. In the 19th century, the British Indian government sought to open up the route to British trade, leading to their suzerainty over Sikkim with its strategic Nathu La and Jelep La passes into the Chumbi Valley. Following the Anglo-Chinese treaty of 1890 and Younghusband expedition, the British established trading posts at Yatung and Lhasa, along with military detachments to protect them. These trade relations continued till 1959, when the Chinese government terminated them.[8]

Indian intelligence officials state that China had been carrying out a steady military build-up in the Chumbi Valley, building many garrisons and converting the valley into a strong military base.[9] In 1967, border clashes occurred at Nathu La and Cho La passes, when the Chinese contested the Indian demarcations of the border on the Dongkya range. In the ensuing artillery fire, states scholar Taylor Fravel, many Chinese fortifications were destroyed as the Indians controlled the high ground.[10] In fact, the Chinese military is believed to be in a weak position in the Chumbi Valley because the Indian and Bhutanese forces control the heights surrounding the valley.[11][12]

The desire for heights is thought to bring China to the Doklam plateau at the southern border of the Chumbi Valley.[13] Indian security experts mention three strategic benefits to China from a control of the Doklam plateau. First, it gives it a commanding view of the Chumbi valley itself. Second, it outflanks the Indian defences in Sikkim which are currently oriented northeast towards the Dongkya range. Third, it overlooks the strategic Siliguri Corridor to the south. A claim to the Mount Gipmochi and the Zompelri ridge would bring the Chinese to the very edge of the Himalayas, from where the slopes descend into the southern foothills of Bhutan and India. From here, the Chinese would be able to monitor the Indian troop movements in the plains or launch an attack on the vital Siliguri corridor in the event of a war. To New Delhi, this represents a "strategic redline".[14][11][15] Scholar Caroline Brassard states, "its strategic significance for the Indian military is obvious."[16]

History

According to the Sikkimese tradition, when the Kingdom of Sikkim was founded in 1642, it included the Chumbi Valley, the Haa Valley to the east as well as the Darjeeling and Kalimpong areas to the south. During the 18th century, Sikkim faced repeated raids from Bhutan and these areas often changed hands. After a Bhutanese attack in 1780, a settlement was reached, which resulted in the transfer of the Haa valley and the Kalimpong area to Bhutan. The Doklam plateau sandwiched between these regions is likely to have been part of these territories. The Chumbi Valley was still said to have been under the control of Sikkim at this point.[18][19]

Historians qualify this narrative, Saul Mullard states that the early kingdom of Sikkim was very much limited to the western part of modern Sikkim. The eastern part was under the control of independent chiefs, who did face border conflicts with the Bhutanese, losing the Kalimpong area.[20] The possession of the Chumbi Valley by the Sikkimese is uncertain, but the Tibetans are known to have fended off Bhutanese incursions there.[21]

After the unification of Nepal under the Gorkhas in 1756, Nepal and Bhutan had coordinated their attacks on Sikkim. Bhutan was eliminated from the contest by an Anglo-Bhutanese treaty in 1774.[22] Tibet enforced a settlement between Sikkim and Nepal, which is said to have irked Nepal. Following this, by 1788, Nepal occupied all of the Sikkim areas to the west of the Teesta river as well as four provinces of Tibet.[23] Tibet eventually sought the help of China, resulting in the Sino-Nepalese War of 1792. This proved to be a decisive entry of China into the Himalayan politics. The victorious Chinese General ordered a land survey, in the process of which the Chumbi valley was declared as part of Tibet.[24] The Sikkimese resented the losses forced on them in the aftermath of the war.[25]

In the following decades, Sikkim established relations with the British East India Company and regained some of its lost territory after an Anglo-Nepalese War. However, the relations with the British remained rocky and the Sikkimese retained loyalties to Tibet. The British attempted to enforce their suzerainty via the Treaty of Tumlong in 1861. In 1890, they sought to exclude the Tibetans from Sikkim by establishing a treaty with the Chinese, who were presumed to be exercising suzerainty over Tibet. The Anglo-Chinese treaty recognised Sikkim as a British protectorate and defined the border between Sikkim and Tibet as the northern watershed of the Teesta River (on the Dongkya range), starting at "Mount Gipmochi". In 1904, the British signed another treaty with Tibet, which confirmed the terms of the Anglo-Chinese treaty. The boundary established between Sikkim and Tibet in the treaty still survives today, according to scholar John Prescott.[26]

See also

References

- "Sikkim impasse: What is the India-China-Bhutan border standoff?".

- Glossary of Tibetan Terms Archived 2008-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Tibet and Francis Younghusband

- East India (Tibet): Papers Relating to Tibet [and Further Papers ..., Issues 2-4, p. 143

- Walcott, Bordering the Eastern Himalaya (2010), p. 64.

- Garver, Protracted Contest (2011), p. 167.

- Walcott, Bordering the Eastern Himalaya (2010), p. 64, 67–68; Smith, Bhutan–China Border Disputes and Their Geopolitical Implications (2015), p. 31; Van Praagh, Great Game (2003), p. 349; Kumar, Acharya & Jacob, Sino-Bhutanese Relations (2011), p. 248

- Walcott, Bordering the Eastern Himalaya (2010), p. 70; Chandran & Singh, India, China and Sub-regional Connectivities (2015), pp. 45–46; Aadil Brar (12 August 2017), "The Hidden History Behind the Doklam Standoff: Superhighways of Tibetan Trade", The Diplomat, archived from the original on 22 August 2017

- Bajpai, China's Shadow over Sikkim (1999), p. vii.

- Fravel, Strong Borders, Secure Nation (2008), p. 198.

- Lt Gen H. S. Panag (8 July 2017), "India-China standoff: What is happening in the Chumbi Valley?", Newslaundry, archived from the original on 18 August 2017

- Ajai Shukla (4 July 2017), "The Sikkim patrol Broadsword", Business Standard, archived from the original on 22 August 2017

- "'Bhutan Raised Doklam at All Boundary Negotiations with China' (Interview of Amar Nath Ram)", The Wire, 21 August 2017, archived from the original on 23 August 2017

- Ankit Panda (13 July 2017), "The Political Geography of the India-China Crisis at Doklam", The Diplomat, archived from the original on 14 July 2017

- Bhardwaj, Dolly (2016), "Factors which influence Foreign Policy of Bhutan", Polish Journal of Political Science, 2 (2): 30

- Brassard, Caroline (2013), "Bhutan: Cautiously Cultivated Positive Perception", in S. D. Muni; Tan, Tai Yong (eds.), A Resurgent China: South Asian Perspectives, Routledge, p. 76, ISBN 978-1-317-90785-5, archived from the original on 27 August 2017

- Sir Clements Robert Markham (1876). Narratives of the Mission of George Bogle to Tibet and of the Journey of Thomas Manning to Lhasa. Trübner and Co.

- Harris, Area Handbook for Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim (1977), pp. 387–388.

- Chandran & Singh, India, China and Sub-regional Connectivities (2015), pp. 45–46.

- Mullard, Opening the Hidden Land (2011), pp. 147-150.

- Shakabpa, Tibet: A Political History (1984), p. 122.

- Banerji, Arun Kumar (2007), "Borders", in Jayanta Kumar Ray (ed.), Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World, Pearson Education India, p. 196, ISBN 978-81-317-0834-7

- Shakabpa, Tibet: A Political History (1984), p. 157.

- Bajpai, China's Shadow over Sikkim (1999), pp. 17-19.

- Mullard, Opening the Hidden Land (2011), pp. 178–179.

- Mullard, Opening the Hidden Land (2011), pp. 183–184; Prescott, Map of Mainland Asia by Treaty (1975), pp. 261–262; Shakabpa, Tibet: A Political History (1984), p. 217; Phuntsho, The History of Bhutan (2013), p. 405

Bibliography

- Scholarly sources

- Bajpai, G. S. (1999), China's Shadow Over Sikkim: The Politics of Intimidation, Lancer Publishers, ISBN 978-1-897829-52-3

- Chandran, D. Suba; Singh, Bhavna (2015), India, China and Sub-regional Connectivities in South Asia, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-93-5150-326-2

- Fravel, M. Taylor (2008), Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China's Territorial Disputes, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-4008-2887-6

- Garver, John W. (2011), Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century, University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-80120-9

- Harris, George L. (1977) [first published by American University, 1964], Area Handbook for Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim (second ed.), U.S. Government Printing Office

- Joshi, Manoj (2017), Doklam: To start at the very beginning, Observer Research Foundation

- Kumar, Pranav; Acharya, Alka; Jacob, Jabin T. (2011). "Sino-Bhutanese Relations". China Report. 46 (3): 243–252. doi:10.1177/000944551104600306. ISSN 0009-4455.

- Mathou, Thierry (2004), "Bhutan–China Relations: Towards a New step in Himalayan Politics" (PDF), The Spider and The Piglet: Proceedings of the First International Seminar on Bhutanese Studies, Thimpu: The Centre for Bhutan Studies

- Mullard, Saul (2011), Opening the Hidden Land: State Formation and the Construction of Sikkimese History, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-20895-7

- Penjore, Dorji (2004), "Security of Bhutan: walking between the giants" (PDF), Journal of Bhutan Studies

- Phuntsho, Karma (2013), The History of Bhutan, Random House India, ISBN 978-81-8400-411-3

- Prescott, John Robert Victor (1975), Map of Mainland Asia by Treaty, Melbourne University Press, ISBN 978-0-522-84083-4

- Rose, Leo E. (1971), Nepal – Strategy for Survival, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-01643-9

- Shakabpa, Tsepon Wangchuk Deden (1984) [first published Yale University Press 1967], Tibet: A Political History, New York: Potala Publications, ISBN 978-0-9611474-0-2

- Singh, Mandip (2013), Critical Assessment of China's Vulnerabilities in Tibet (PDF), Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses, ISBN 978-93-82169-10-9

- Smith, Paul J. (2015), "Bhutan–China Border Disputes and Their Geopolitical Implications", in Bruce Elleman; Stephen Kotkin; Clive Schofield (eds.), Beijing's Power and China's Borders: Twenty Neighbors in Asia, M.E. Sharpe, pp. 23–36, ISBN 978-0-7656-2766-7

- Van Praagh, David (2003), Greater Game: India's Race with Destiny and China, McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, pp. 349–, ISBN 978-0-7735-7130-3

- Walcott, Susan M. (2010), "Bordering the Eastern Himalaya: Boundaries, Passes, Power Contestations" (PDF), Geopolitics, 15: 62–81, doi:10.1080/14650040903420396

- Primary sources

- China Foreign Ministry (2 August 2017), The Facts and China's Position Concerning the Indian Border Troops' Crossing of the China-India Boundary in the Sikkim Sector into the Chinese Territory (2017-08-02) (PDF), Government of China, retrieved 15 August 2017

- India. Ministry of External Affairs (1966), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged Between the Governments of India and China, January 1965–February 1966, White Paper No. XII (PDF)

- India. Ministry of External Affairs (1967), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged Between the Governments of India and China, February 1966–February 1967, White Paper No. XIII (PDF)

- India. Ministry of External Affairs (1967), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged Between the Governments of India and China, February 1967–April 1968, White Paper No. XIV (PDF)

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.