Cincinnati riot of 1853

The Cincinnati riot of 1853 was triggered by the visit of then-Archbishop (later, Cardinal) Gaetano Bedini, the emissary of Pope Pius IX, to Cincinnati, Ohio, on 21 December 1853. The German Liberal population of the city, many of whom had come to America after the Revolutions of 1848, identified Cardinal Bedini with their reactionary opponents.[1] An armed mob of about 500 German men with 100 women following marched on the home of Bishop John Purcell, protesting the visit. One protester was killed and more than 60 were arrested.[2]

Background

Bedini was sent to America to deal with a number of disputes over church property. The central argument was over whether ownership of a church and its land should remain with the board of trustees appointed by the congregation or transferred to the bishop as representative of the church. The issue was controversial since many Protestants and liberals thought that the "Church of Rome" had no right to own property in the United States. Unfortunately, Bedini lacked tact and experience in diplomacy and was already despised by many Americans for his minor role in helping the pope overthrow the Roman Republic in 1849.[3]

At the time of Bedini's visit, anti-Catholic feelings were strong in Cincinnati.

Archbishop John Purcell had alienated many people by objecting to taxing Catholics for support of public schools.[4] Hearing of Bedini's visit, the Daily Commercial printed a very unfavorable article, and the Freemen's Hochwächter started printing scurrilous articles calling him the "Butcher of Bologna". The nativist Know-Nothing Party singled Bedini out as a target for attack. The German-American "Forty Eighters" of Cincinnati were fully supported of the Nativists.[1] However, Cincinnati's German-Americans were far from unified. The Dreissiger (Thirtiers), who had left Germany in the 1830s to escape political repression, were against activism, and the German Catholics defended their religion.[5]

On the day of Bedini's arrival, the Hochwächter published an article that began: "Reader, dost thou know who Bedini is? Lo! there is blood on his hands – human blood! Lo! the skin will not leave his hands which at his command was flayed from Ugo Bassi! Lo! a murderer, a butcher of men." The article went on to essentially demand Bedini's assassination, appealing specifically to the Freimänner (Society of Freemen), about 1,200 men with a meeting house in the Over-the-Rhine section of the city.[1]

The march

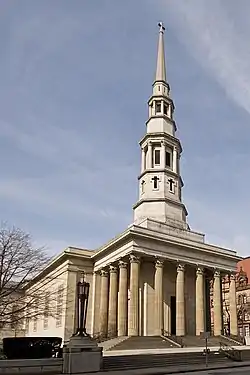

On Christmas Day, Bedini preached in French and German at the Saint Peter in Chains Cathedral.[6] Meanwhile, the Freimänner called for a meeting in the morning to prepare for a demonstration, inviting other groups, and spent the afternoon making effigies, banners and placards.

The Mayor was informed what was afoot and ordered the Chief of Police, Captain Thomas Lukens, to investigate. Certain that there would be no trouble on Christmas Day, the mayor then went home to his family. Soon after, Captain Lukens heard that the march had started. He ordered 100 policemen to a post opposite the Bishop's Chancery beside the cathedral.[1]

The march began soon after 10 p.m., with over 500 men led by a drum section, and followed by 100 women. Several of the men carried a wooden scaffold from which the Cardinal was hanging in effigy. The banners and placards read, "Down with Bedini!" "No Priests, No Kings." "Down with the Butchers of Rome!" "Down with the Papacy!"[7]

When the police advanced to meet the demonstrators, one of the marchers fired a shot. The police charged and a general brawl ensued in which two policemen and fifteen German demonstrators were wounded, one fatally. Over 60 demonstrators were arrested.[1]

Aftermath

The legal proceedings that followed were strongly biased in favor of the Germans. After the police had testified, the prosecuting attorney, William M. Dickson,[1][8] said no proof had been given that there was intent to do violence to Cardinal Bedini. The court then dismissed the indictment on the basis that the case had been abandoned by the prosecution. The publisher of the Hochwachter was arrested, but later discharged when no proof was found of a conspiracy to murder the Nuncio. A meeting was called to protest the arrests and demand that the mayor resign. Although the mayor kept his job, the Chief of Police was dismissed.[1]

In his report to the Holy See, the Nuncio described the aftermath, "In Cincinnati, the demagogic rage of Europe surfaced with a vengeance. The German Revolutionary sentiment, which I have described elsewhere, launched their attack against this 'tyrant of Italian patriots' and the effect was truly tremendous. ... The fact is that the language of the American bishops began to change. Before Cincinnati they urged me not to be afraid, to go forward and not go back: afterwards, I began to hear repeated suggestions that it would be better if I returned to Europe."[9]

Feelings ran so high in the later part of Bedini's visit that in New York City he had to be smuggled into the ship for his return voyage.[10]

Although Cincinnati's Nativists had supported the German demonstrators, the incident continued to feed controversy over foreign immigration to America. Ultimately, the riot directly contributed to the rise of the anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic Know-Nothing Party and to conflicts with recent immigrants.[11]

Two years later, in the Cincinnati riots of 1855, a mob of Know-Nothing supporters carried out a pogrom of the German immigrants in Over-the-Rhine.[12]

See also

References

- James F. Connelly (1960). The visit of Archbishop Gaetano Bedini to the United States of America: June 1853-February 1854. Editrice Pontificia Università Gregoriana. p. 96ff. ISBN 88-7652-082-1. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- Joseph M. White (2007). Worthy of the Gospel of Christ: A History of the Catholic Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 1-59276-229-8. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- Tyler Anbinder (1994). Nativism and slavery: the northern Know Nothings and the politics of the 1850s. Oxford University Press US. p. 27. ISBN 0-19-508922-7. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- Frederick J. Blue (1987). Salmon P. Chase: a life in politics. Kent State University Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-87338-340-0.

- Andrew Robert Lee Cayton (2002). Ohio: the history of a people. Ohio State University Press. p. 145. ISBN 0-8142-0899-1.

- Roger Antonio Fortin (2002). Faith and action: a history of the Catholic Archdiocese of Cincinnati, 1821-1996. Ohio State University Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-8142-0904-1.

- Massimo Franco, Parallel Empires: The Vatican and the United States - Two Centuries of Alliance and Conflict, Doubleday, 2008. Page 13.

- Greve, Charles Theodore (1904). Centennial History of Cincinnati and Representative Citizens. Biographical Publishing Company. pp. 769.

- Franco (2008), page 14.

- William E. Gienapp (1988). The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856. Oxford University Press US. p. 94. ISBN 0-19-505501-2. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- Margaret C. DePalma (2004). Dialogue on the frontier: Catholic and Protestant relations, 1793-1883. Kent State University Press. p. xiv. ISBN 0-87338-814-3. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- John Kiesewetter (July 15, 2001). "Civil unrest woven into city's history". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2010-10-25.