Circuit satisfiability problem

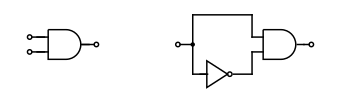

In theoretical computer science, the circuit satisfiability problem (also known as CIRCUIT-SAT, CircuitSAT, CSAT, etc.) is the decision problem of determining whether a given Boolean circuit has an assignment of its inputs that makes the output true.[1] In other words, it asks whether the inputs to a given Boolean circuit can be consistently set to 1 or 0 such that the circuit outputs 1. If that is the case, the circuit is called satisfiable. Otherwise, the circuit is called unsatisfiable. In the figure to the right, the left circuit can be satisfied by setting both inputs to be 1, but the right circuit is unsatisfiable.

CircuitSAT is closely related to Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT), and likewise, has been proven to be NP-complete.[2] It is a prototypical NP-complete problem; the Cook–Levin theorem is sometimes proved on CircuitSAT instead of on the SAT and then reduced to the other satisfiability problems to prove their NP-completeness.[1][3] The satisfiability of a circuit containing arbitrary binary gates can be decided in time .[4]

Proof of NP-Completeness

Given a circuit and a satisfying set of inputs, one can compute the output of each gate in constant time. Hence, the output of the circuit is verifiable in polynomial time. Thus Circuit SAT belongs to complexity class NP. To show NP-hardness, it is possible to construct a reduction from 3SAT to Circuit SAT.

Suppose the original 3SAT formula has variables , and operators (AND, OR, NOT) . Design a circuit such that it has an input corresponding to every variable and a gate corresponding to every operator. Connect the gates according to the 3SAT formula. For instance, if the 3SAT formula is the circuit will have 3 inputs, one AND, one OR, and one NOT gate. The input corresponding to will be inverted before sending to an AND gate with and the output of the AND gate will be sent to an OR gate with

Notice that the 3SAT formula is equivalent to the circuit designed above, hence their output is same for same input. Hence, If the 3SAT formula has a satisfying assignment, then the corresponding circuit will output 1, and vice versa. So, this is a valid reduction, and Circuit SAT is NP-hard.

This completes the proof that Circuit SAT is NP-Complete.

Restricted Variants and Related Problems

Planar Circuit SAT

Assume that we are given a planar Boolean circuit (i.e. a Boolean circuit whose underlying graph is planar) containing only NAND gates with exactly two inputs. Planar Circuit SAT is the decision problem of determining whether this circuit has an assignment of its inputs that makes the output true. This problem is NP-complete.[5] In fact, if the restrictions are changed so that any gate in the circuit is a NOR gate, the resulting problem remains NP-complete.[5]

Circuit UNSAT

Circuit UNSAT is the decision problem of determining whether a given Boolean circuit outputs false for all possible assignments of its inputs. This is the complement of the Circuit SAT problem, and is therefore Co-NP-complete.

Reduction from CircuitSAT

Reduction from CircuitSAT or its variants can be used to show NP-hardness of certain problems, and provides us with an alternative to dual-rail and binary logic reductions. The gadgets that such a reduction needs to construct are:

- A wire gadget. This gadget simulates the wires in the circuit.

- A split gadget. This gadget guarantees that all the output wires have the same value as the input wire.

- Gadgets simulating the gates of the circuit.

- A True terminator gadget. This gadget is used to force the output of the entire circuit to be True.

- A turn gadget. This gadget allows us to redirect wires in the right direction as needed.

- A crossover gadget. This gadget allows us to have two wires cross each other without interacting.

Minesweeper Inference Problem

This problem asks whether it is possible to locate all the bombs given a Minesweeper board. It has been proven to be CoNP-Complete via a reduction from Circuit UNSAT problem.[6] The gadgets constructed for this reduction are: wire, split, AND and NOT gates and terminator.[7] There are three crucial observations regarding these gadgets. First, the split gadget can also be used as the NOT gadget and the turn gadget. Second, constructing AND and NOT gadgets is sufficient, because together they can simulate the universal NAND gate. Finally, since we can simulate XOR with three NANDs, and since XOR is enough to build a crossover, this gives us the needed crossover gadget.

The Tseytin transformation

The Tseytin transformation is a straightforward reduction from Circuit-SAT to SAT. The transformation is easy to describe if the circuit is wholly constructed out of 2-input NAND gates (a functionally-complete set of Boolean operators): assign every net in the circuit a variable, then for each NAND gate, construct the conjunctive normal form clauses (v1 ∨ v3) ∧ (v2 ∨ v3) ∧ (¬v1 ∨ ¬v2 ∨ ¬v3), where v1 and v2 are the inputs to the NAND gate and v3 is the output. These clauses completely describe the relationship between the three variables. Conjoining the clauses from all the gates with an additional clause constraining the circuit's output variable to be true completes the reduction; an assignment of the variables satisfying all of the constraints exists if and only if the original circuit is satisfiable, and any solution is a solution to the original problem of finding inputs that make the circuit output 1.[1][8] The converse—that SAT is reducible to Circuit-SAT—follows trivially by rewriting the Boolean formula as a circuit and solving it.

See also

- Circuit Value Problem

- Structured Circuit Satisfiability

- Satisfiability problem

References

- David Mix Barrington and Alexis Maciel (July 5, 2000). "Lecture 7: NP-Complete Problems" (PDF).

- Luca Trevisan (November 29, 2001). "Notes for Lecture 23: NP-completeness of Circuit-SAT" (PDF).

- See also, for example, the informal proof given in Scott Aaronson's lecture notes from his course Quantum Computing Since Democritus.

- Sergey Nurk (December 1, 2009). "An O(2^{0.4058m}) upper bound for Circuit SAT".

- "Algorithmic Lower Bounds: Fun With Hardness Proofs at MIT" (PDF).

- Scott, Allan; Stege, Ulrike; van Rooij, Iris (2011-12-01). "Minesweeper May Not Be NP-Complete but Is Hard Nonetheless". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 33 (4): 5–17. doi:10.1007/s00283-011-9256-x. ISSN 1866-7414.

- Kaye, Richard. Minesweeper is NP-complete (PDF).

- Marques-Silva, João P. and Luís Guerra e Silva (1999). "Algorithms for Satisfiability in Combinational Circuits Based on Backtrack Search and Recursive Learning" (PDF).